AN EVALUATION OF FADING PROCEDURES IN THE TREATMENT OF

PEDIATRIC FEEDING DISORDERS: A COMPONENT ANALYSIS

A Thesis

Presented to the faculty of the Department of Psychology

California State University, Sacramento

Submitted in partial satisfaction of

the requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF ARTS

in

Psychology

(Applied Behavior Analysis)

by

Jillian K. LaBrie

FALL

2012

© 2012

Jillian K. LaBrie

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ii

AN EVALUATION OF FADING PROCEDURES IN THE TREATMENT OF

PEDIATRIC FEEDING DISORDERS: A COMPONENT ANALYSIS

A Thesis

by

Jillian K. LaBrie

Approved by:

__________________________________, Committee Chair

Dr. Becky Penrod

__________________________________, Second Reader

Dr. Caio Miguel

__________________________________, Third Reader

Dr. Linda Copeland

____________________________

Date

iii

Student: Jillian K. LaBrie

I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University

format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to

be awarded for the thesis.

__________________________, Graduate Coordinator

Dr. Lisa Harrison

Department of Psychology

iv

___________________

Date

Abstract

of

AN EVALUATION OF FADING PROCEDURES IN THE TREATMENT OF

PEDIATRIC FEEDING DISORDERS: A COMPONENT ANALYSIS

by

Jillian K. LaBrie

In the treatment of food selectivity, packages consisting of multiple components are

typically utilized, often including an escape extinction procedure. Previous research has

demonstrated that these treatment packages are successful in increasing consumption of

target foods, as well as decreasing inappropriate mealtime behaviors. However, due to

initial negative side effects of escape extinction (i.e., an immediate increase in

inappropriate mealtime behaviors), caregivers may be likely implement and/or to adhere

to the procedures. The current study investigated the role of less intrusive interventions

prior to the introduction of escape extinction. Specifically, the current study evaluated

various fading procedures (e.g., texture and liquid fading) using a component analysis by

first introducing fading, then differential reinforcement, and finally escape extinction,

when needed. Results indicated that escape extinction may not be necessary in all cases

v

and contribute evidence to the recommendation to include and/or start with antecedent

based interventions when treating food refusal.

_______________________, Committee Chair

Dr. Becky Penrod

_______________________

Date

vi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many people in my life have contributed to where I am today, from childhood to

my undergraduate and post-graduate education. I would like to give special thanks to my

advisors, cohort, friends, and finally my family. Dr. Becky Penrod, you are a remarkable

person, clinician, and advisor/mentor; I am privileged to have had the opportunity to

work with and learn so much from you, both academically and professionally. Dr. Caio

Miguel, you provided me with wonderful experiences that I would have never had the

opportunity to be a part of it weren’t for you. Thank you both so much for all you have

done for me academically, professionally, and personally.

Next, I would like to acknowledge my amazing cohort, Jonathan Fernand,

Kathryn Lee, and Michelle Sutherland. Learning from and working with all of you has

been a priceless experience that I will cherish for the rest of my life. I would also like to

thank the individuals who I had the pleasure of learning from and consequently shaped

my love for behavior analysis as an undergraduate at the University of Nevada, Reno,

most notably, Molly Day Dubuque and Jillian DeFreitas. In addition, I could not have

completed this project without the help of Krista Bolton and support from my other

colleagues at Sacramento State.

Lastly, I would not be here if it were not for the support of my family. Thank

you, mom for always encouraging my education, both formally and informally, as well as

supporting me even when we didn’t see eye to eye. To my husband, Brian Lewis, thank

you for always having faith in my goals and supporting me during the toughest times.

vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... vii

List of Tables .............................................................................................................. ix

List of Figures ............................................................................................................... x

Chapter

1. INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................… 1

Stimulus Fading Procedures ............................................................................. 4

Stimulus Fading in the Treatment of Feeding Disorders ................................. 6

Demand Fading ..................................................................................... 7

Simultaneous Presentation with Fading ................................................ 9

Apparatus and Distance Fading .......................................................... 13

Texture Fading .................................................................................... 14

Summary ......................................................................................................... 16

Purpose of the Study ....................................................................................... 16

2. METHOD ............................................................................................................. 18

Participants and Setting................................................................................... 18

Response Measurement and Data Collection ................................................. 19

Interobserver Agreement and Treatment Integrity ......................................... 21

Food Preparation ............................................................................................ 24

Experimental Design ...................................................................................... 27

Assessments .................................................................................................... 27

Procedures ....................................................................................................... 30

3. RESULTS ............................................................................................................. 35

4. DISCUSSION ....................................................................................................... 51

Appendix Data Sheets………………………………………………………………. 61

References................................................................................................................... 64

viii

LIST OF TABLES

Tables

Page

1. Fading steps: Liquid ……… ...........................................………………………… 24

2. Fading steps: Texture ………..……………….… ..............……………………… 25

3. Fading steps: Demand (Bolus size)…...…………….….....……………………… 26

ix

LIST OF FIGURES

Figures

Page

1. Bastion Paired-Choice Preference Assessment (Purees)…………………….....… 36

2. Bastion Pre/Post Paired-Choice Preference Assessment (Final Form)…….…….. 37

3. Vincent Paired-Choice Preference Assessment (Preferred Foods)…………….… 37

4. Vincent Paired-Choice Preference Assessment (Toys #1)……………………….. 38

5. Vincent Reinforcer Assessment (Toys #1)......…………………………………… 39

6. Vincent Paired-Choice Preference Assessment (Toys #2)...................................... 40

7. Vincent Reinforcer Assessment (Toys #2).....……………………………………. 40

8. Bastion Percentage of Bites Consumed without Expulsions……..………………. 43

9. Bastion Percentage of Inappropriate Mealtime Behaviors per session………..…. 45

10. Vincent Percentage of Bites Consumed without Expulsions…………………… 47

11. Vincent Percentage of Inappropriate Mealtime Behaviors per session…………. 50

x

1

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

Food selectivity and inappropriate mealtime behaviors have been reported to be

problematic for typically developing children, as well as children with autism spectrum

disorders, developmental disabilities, and intellectual disabilities (Ahearn, Castine, Nault,

& Green, 2001; Bandini, et al., 2010; Gal, Hardal-Nasser, Engel-Yeger, 2011; Schreck,

Williams, Smith, 2004; Volkert & Vaz, 2010; Williams, Gibbons, Schreck, 2005).

Furthermore, children with autism are more likely than typically developing children to

display problems with feeding (restricted intake by type and texture, refuse novel foods)

(Schreck, et al.). It has been reported that up to 25% of typically developing children

(Williams et al.) and 90% of children with autism (Volkert & Vaz) display feeding

difficulties and/or food selectivity. In addition, one study found that 97% of children with

intellectual disabilities that participated exhibited some sort of feeding-related deficit

(e.g., oral motor) and/or food refusal/selectivity (Gal et al.). Moreover, numerous

negative outcomes have been reported for individuals that have been diagnosed with

feeding disorders or who display some type of food refusal behavior. First, individuals,

especially infants and children, who do not consume enough volume or variety of food,

may be at risk for developing preventable health issues and illnesses (Nicklas, 2003;

Reynolds, et al., 1999). Additionally, an individual’s growth and development may be

hindered due to deficient weight gain (Riordan, Iwata, Finney, Wohl, & Stanley, 1984).

Inadequate intake due to a limited variety of foods in an individual’s diet can contribute

2

to a deficiency in essential vitamins and nutrients (Nicklas; Reynolds et al.).

Furthermore, inadequate food intake and nutrition can lead to inhibited brain

development which may be accompanied by learning and academic difficulties (Bryan,

Osendarp, Hughes, Calvaresi, Baghurst, & Van Klinken, 2004; Dykman, Casey,

Ackerman, & McPherson, 2001), and children diagnosed with severe feeding disorders

have a greater chance of being diagnosed with other developmental delays (Ahearn,

Kerwin, Eicher, & Lukens, 2001). Additionally, childhood feeding problems can lead to

disruptive or high stress mealtimes for the family or primary feeder, which can also have

an effect on potential socialization opportunities. A child with challenging mealtime

behavior may not be included in the family meal and instead fed at a different time or in a

different area of the home so as to avoid unpleasant or stressful mealtime situations.

An individual may develop food selectivity in regards to one or many different

physical or sensory properties of food or the mealtime environment. Food selectivity

may develop due to a negative experience, physiological abnormalities (e.g., cleft palate

and swallowing difficulties), physical/developmental disabilities (e.g., cerebral palsy and

autism) and/or other underlying medical conditions. Some possible events, which may

contribute to food aversions, include choking, gagging, vomiting, indigestion, or other

uncomfortable physiological events. The properties of the item to which the child has

developed an aversion may also generalize to other food items that share similar physical

(e.g., size and color) or sensory (e.g., olfactory, gustatory, and tactile) characteristics of

the original item. An individual may display selectivity by type, texture, color, brand,

and/or taste. In addition, the presentation of food such as shape (e.g., how the food is cut)

3

or temperature, as well as the location of the meal and eating utensils (e.g., spoon, plates,

etc.) can play a role in an individual’s food selectivity and inappropriate mealtime

behaviors.

There is a broad range of feeding difficulties that can be categorized as food

selectivity by type, such as refusal to eat items from particular food groups (e.g.,

vegetables), only consuming snack or junk foods, and refusal to consume liquids (i.e.,

total liquid refusal or liquid selectivity). Food selectivity of any kind can lead to harmful

nutritional and developmental consequences. For instance, if a child does not consume a

sufficient amount of liquids it could lead to dehydration. Another type of feeding

difficulty of concern is food selectivity by texture. An individual that displays selectivity

by texture may only consume food in a puree form and the variety of food types in their

repertoire may be limited. In this example, if a child does not have the opportunity to

advance to age-appropriate textures, they may run the risk of underdeveloped oral motor

skills (Southall & Martin, 2010) and potentially low muscle tone that could contribute to

poor caloric intake. In addition to these health concerns, there may be negative social

consequences associated with various forms of food selectivity. For instance, an

individual that displays selectivity by texture may be isolated or teased by peers for

eating food not typically presented in a puree form. Children with feeding disorders may

stand out from their peers by not participating in events with peers (e.g., birthday parties)

because they don’t eat the same foods as their peers (e.g., birthday cake, pizza, hotdogs,

etc.). These children may stand out more by bringing their own food to peer-related or

other events because of refusal to try new things and/or a limited food repertoire. In

4

summary, feeding problems, particularly food selectivity, can result in deleterious effects

upon the individual by contributing to potential oral motor delays, nutritional and

developmental deficiencies, as well as impeding socialization opportunities.

Stimulus Fading Procedures

Previous studies have demonstrated the effective use of fading procedures in the

reduction of behavior excesses that interfere with an individual’s daily functioning, as

well as increasing skills that would otherwise restrict an individual from participation in

certain activities that are beneficial to their survival or wellbeing (e.g., Shabani & Fisher,

2006). For instance, fear or aversions to preventative or necessary medical procedures or

simply visiting a doctor can have detrimental consequences for an individual.

Additionally, and even more relevant to this study, are challenging behaviors associated

with feeding disorders.

Antecedent interventions, such as stimulus fading, can be used to eliminate or

minimize the motivating operation for negatively reinforced behavior by altering the

value of escape as a reinforcer (Michael, 1982, 1993; Zarcone, Iwata, Smith, Mazaleski,

& Lerman, 1994). Stimulus fading can be used in an effort to reduce inappropriate

behaviors, as well as facilitate acquisition of new responses (e.g., McCord, Iwata,

Galensky, Ellingson, & Thomson, 2001; Ringdahl, Kitsukawa, Andelman, Call,

Winborn, Barretto, & Reed, 2002; Zarcone et al., 1994). In particular, one variation of

stimulus fading, known as demand fading, has been attributed to an immediate reduction

of maladaptive behaviors (e.g., self-injurious behavior) maintained by negative

reinforcement in the form of escape from instructional demands while remediating the

5

effects of an extinction burst when used in conjunction with escape extinction (EE), as

opposed to EE without the use of demand fading for two of three participants (Zarcone,

Iwata, Vollmer, Jagtiani, Smith, & Mazaleski, 1993).

Previous research has demonstrated the utility of implementing a stimulus fading

procedure for behaviors maintained by negative reinforcement (McCord et al., 2001;

Reitman & Passeri, 2008; Ringdahl et al., 2002; Shabani & Fisher, 2006). Specifically,

Shabani and Fisher used a stimulus fading procedure combined with differential

reinforcement of other behaviors for an adolescent with autism who had a needle phobia.

It was necessary for the participant to learn to accept blood being drawn in order to

manage his diabetes and specifically monitor his glucose levels. Shabani and Fisher used

stimulus fading in order to decrease behaviors maintained by negative reinforcement

(e.g., crying, screaming, elopement, self-injury, aggression, and pulling away from the

needle) when in the presence of needles. For this study, the initial criterion was set based

on the participant not displaying any of the target problem behaviors when the proximity

of the needle was a certain distance from his hand. This initial criterion was used to

ensure the participant would come into contact with the reinforcement contingency.

During each phase, the distance of the needle from the participant’s hand was gradually

decreased following two or three sessions without the participant’s hand moving more

than 3cm in a 10-s trial. Follow-up data taken two months later demonstrated that results

of the intervention were maintained.

In another study, Reitman and Passeri (2008) taught a child diagnosed with

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder to swallow a pill by using a fading procedure in

6

which the size of pieces of candy to be swallowed was systematically increased and

eventually the child’s medication (Ritalin) was targeted. The treatment package included

modeling, differential reinforcement using tangible items, and stimulus fading. EE was

not necessary and there was a 50 min session cap for all phases of treatment. The

participant met terminal criterion within 15 sessions (approximately 100 trials), and

responding was maintained at both 3- and 12-month follow-up sessions. Reitman and

Passeri were successful in demonstrating the effectiveness of stimulus fading without the

use of an EE procedure. Even though EE was not necessary for acquisition of the target

response, stimulus fading was used as part of a treatment package consisting of

differential reinforcement and modeling which does not allow for conclusions to be

drawn about the contribution of the fading procedure if implemented alone.

Stimulus Fading in the Treatment of Feeding Disorders

Many studies have demonstrated the efficacy of implementing fading procedures

for individuals who demonstrate food selectivity (e.g., Luiselli, Ricciardi, & Gilligan,

2005; Tiger & Hanley, 2006); however, it should be noted that fading procedures are

often used as one component of treatment packages consisting of various behavioral

strategies such as reinforcement, chaining, and EE (e.g., Freeman & Piazza, 1998;

Hagopian, Farrell, & Amari, 1996).

Within-stimulus fading is a strategy that has been effective for remediating the

negative outcomes of acquired food aversion. Within-stimulus fading procedures involve

altering some dimension of the target item or stimulus (e.g., texture, taste, size, color,

shape, amount, etc.) to facilitate acquisition of a desired response (Miltenberger, 2012).

7

Within-stimulus fading procedures focus on the same target response during each

learning opportunity while the physical properties of the associated stimuli progressively

change as mastery occurs. Moreover, when stimulus fading is used, responses or skills

that have been observed to occur in the past are targeted and then the response

requirement is gradually increased as the individual meets criterion with the previous

response requirements. Programming for acquisition in this manner can reduce the

likelihood of errors and thereby reduce the likelihood of negative emotional responses or

inappropriate behaviors (e.g., Shabani & Fisher, 2006).

Research has shown that behavior analytic interventions including fading

components are effective in addressing feeding problems (e.g., Luiselli, 2000; Sharp &

Jaquess, 2009; Tiger & Hanley, 2006). Fading can be advantageous in addressing

feeding problems by gradually exposing and changing relevant antecedent stimuli in

order to decrease problem behaviors and make the events, stimuli, or activities associated

with eating less aversive. Methods of stimulus fading can be applied in many different

ways for the treatment of feeding disorders. Specifically, various fading procedures can

be described as demand fading (bite size or number of bites), apparatus fading, distance

fading, texture fading, and simultaneous presentation with fading. The aforementioned

list of fading procedures is not exhaustive and other variations or combinations could be

utilized. Some variations of fading procedures are outlined below.

Demand Fading

Demand fading or instructional fading, also known as bite fading within the

feeding literature, has been shown to be an effective procedure for increasing

8

consumption of liquids and solids for individuals that display food selectivity and refusal

(e.g., Freeman & Piazza, 1998; Galensky, Miltenberger, Stricker, Garlinghouse, 2001;

Valdimassdottir, Halldorsdottir, & Sigurdardottir, 2010). When demand fading is

implemented, the initial response requirement is small and attainable so as to increase the

likelihood of the individual coming into contact with the predetermined reinforcement

contingency (e.g., termination of the activity, presentation of preferred items, etc.). Once

the behavior is reliably occurring at the minimum response requirement, the frequency of

instructions, or in the case of feeding interventions, the number of bites or amount of

fluid that is required to be consumed is progressively increased in order for the individual

to access reinforcement.

For instance, Hagopian et al., (1996) used backward chaining and fading as an

intervention for total liquid refusal. Backward chaining and fading components were

implemented concurrently such that as success was demonstrated with chained responses

and the response requirement was increased, the volume of liquid intake was also

increased. For this study, backward chaining consisted of three main steps:

1) swallowing, 2) accepting water into the mouth, and 3) bringing the cup of water to the

mouth. Reinforcement was first contacted when the participant swallowed without the

presentation of water or a drinking apparatus, then reinforcement was provided when a

swallow occurred following the presentation of an empty syringe into the participant’s

mouth. Once the participant was consistently accepting and swallowing small amounts

of water with a syringe, the volume of liquid was systematically increased along with the

introduction of a cup as the final drinking apparatus. Hagopian et al. demonstrated that

9

fading without EE might be successful for treating liquid refusal; however, since a

backward chaining procedure was also used, the contribution of the fading procedure is

not entirely clear.

As another example, Freeman and Piazza (1998) demonstrated the efficacy of a

treatment package consisting of bite fading, reinforcement, and EE in increasing

consumption of non-preferred foods for a girl with autism and other diagnoses. Similarly,

Valdimassdottir et al. (2010) were successful in expanding the food repertoire for a child

diagnosed with autism that displayed food selectivity by implementing bite fading and

reinforcer thinning with EE across two caregivers and settings. Additionally, demand

fading combined with reinforcement has been shown to be effective in establishing selffeeding and oral consumption, as well as expanding the number of foods consumed, for a

typically developing young boy that was G-tube dependent (Luiselli, 2000). In summary,

previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of demand fading used in conjunction

with various behavioral strategies, but further research is needed to determine the

individual effects of common procedures (e.g., fading, reinforcement, and extinction)

used in the treatment of pediatric feeding disorders. Treatment for individuals may vary

in that some cases require more comprehensive interventions while others will necessitate

fewer or less intrusive interventions.

Simultaneous Presentation with Fading

Simultaneous presentation of foods or liquids, with demand fading, has been

shown to be an effective treatment for individuals with feeding problems (Luiselli et al.,

2005; Mueller, Piazza, Patel, Kelley, & Pruett, 2004; Patel, Piazza, Kelly, Ochsner,

10

&Santana, 2001; Tiger & Hanley, 2006). Liquid and food blending used in the treatment

of feeding disorders involves increasing consumption of liquids or food through mixing

preferred and non-preferred items or flavors and gradually increasing the amount of

liquids or food that have previously been refused when presented by themselves.

In a study conducted by Patel et al. (2001) a treatment package consisting of

fading with differential reinforcement of alternative behavior (DRA) and EE was used to

increase fluid consumption for one individual. The participant initially refused milk with

Carnation Instant Breakfast (CIB) and water with CIB, but would consume water by

itself. The fading procedure started by slowly introducing CIB mix into water; then, after

the participant was successfully drinking the water mixture with the entire package of

CIB, water was gradually replaced by milk until the solution consisted of only milk and a

whole packet of CIB. Patel et al. were successful in establishing acceptance of CIB

mixed with milk; however, the effect was only demonstrated with one participant.

Similarly, Luiselli et al. (2005) examined the effectiveness of fading alone to

increase the variety of liquids consumed for a girl diagnosed with autism. Prior to

treatment, the participant would independently drink a mixture of 50/50 Pediasure to

milk ratio and refused to consume milk when not mixed with Pediasure (i.e., refused

the presentation of 100% milk). Luiselli et al. increased the milk to Pediasure ratio by

adding approximately 6.3% more milk for each fading step. Baseline and treatment

conditions both included an instruction to take a drink when a 60-s lapse in consumption

occurred and praise was provided contingent upon consumption of the target mixture.

11

Fading alone could have been the contributing variable to the observed success given that

conditions remained constant from baseline to treatment and there was no increase in

consumption of the 100% milk beverage during baseline conditions. On the other hand,

praise may have served as positive reinforcement for liquid consumption or negative

reinforcement by the termination of the instruction may have played a role in treatment

outcomes. However, given that periodic probes were conducted with 100% milk

throughout the fading steps and consumption of the terminal target beverage did not

occur until the final stages of fading, it is likely that fading without the use of EE was a

contributing factor to an increase in milk consumption.

Furthermore, Tiger and Hanley (2006) used stimulus fading, in addition to

reinforcer pairing, in order to establish milk drinking for a typically developing

preschooler. Chocolate syrup, which was reported to be highly preferred, was used as an

antecedent intervention by mixing the syrup with milk and then eventually fading out the

chocolate syrup completely. Success was demonstrated across settings (i.e., preschool

and home), as well as across caregivers (i.e., preschool teacher and parents). Milk

consumption without the use of chocolate was increased to criterion during treatment;

however, plain milk consumption was not maintained at very high levels. The participant

did continue to consume plain milk following the study, but the amount decreased from

treatment. Even though milk consumption was not maintained for the recommended

nutritional percentages, it was increased significantly without the use of EE compared to

consumption prior to treatment.

12

Previous research has also demonstrated the effectiveness of food blending and

fading in conjunction with reinforcement (i.e., DRA or non-contingent reinforcement)

and EE (Mueller et al. 2004). Mueller et al. blended preferred and non- preferred foods

together as a puree and the volume of non-preferred food was increased by about 10% as

participants met criterion for the previous fading step. Consumption increased for the

target foods across both participants following the implementation of the treatment

package. Both participants had a prior feeding intervention, which consisted of

reinforcement and EE; the previous intervention was successful in increasing

consumption of some but not all foods. When the blending and fading procedure was

added to the treatment package the variety of foods consumed for the participants was

expanded even further. These researchers discussed possible mechanisms responsible for

the increase in variety of foods consumed such as the altering of motivating operations or

effects of flavor-flavor conditioning. First, the presentation of preferred foods may have

reduced the aversive properties of the non-preferred foods and decreased the

effectiveness of escape as reinforcement (Michael, 1982, 1993). On the other hand,

pairing of sweet tasting preferred foods with non-preferred foods may have facilitated the

increase in consumption of non-preferred foods through the process of flavor-flavor

conditioning (Zellner, Rozin, Aron, & Kulish, 1983). However, because the treatment

package also utilized a DRA and EE procedure, it is difficult to parse out the utility of the

fading procedure.

13

Apparatus and Distance Fading

Apparatus fading and distance fading have also been demonstrated as effective

treatments for food/liquid refusal and selectivity. For instance, Babbit, Shore, Smith,

Williams, and Coe (2001) used apparatus fading and EE to treat children who would

consume solids but refused liquids. They used a spoon to cup fading procedure and

provided preferred edibles contingent on meeting the response requirement (i.e.,

consumption of liquids) within a given phase. Participants began by receiving liquids on

a spoon with a cup attached to the handle (farthest away from the head of the spoon)

which was gradually moved closer to the head of the spoon until participants were

drinking from the cup with the spoon no longer attached. The fading procedure, in

conjunction with EE, was effective in increasing cup drinking for both participants in the

study.

A study conducted by Rivas, Piazza, Patel, and Bachmeyer (2010) examined

spoon distance fading with and without EE, as well as EE alone. They found that

distance fading alone was somewhat effective. Distance fading was effective until the

distance of the spoon from the participant’s lips was reduced and a reemergence of

inappropriate mealtime behaviors occurred. Fading with EE was successful in increasing

acceptance, however, when compared with EE alone, fading with EE resulted in slower

progress and more trials to criterion. On the other hand, when fading was combined with

EE a reduction in inappropriate mealtime behaviors was observed immediately, as

opposed to an extinction burst that occurred when EE was implemented in isolation.

Rivas et al. demonstrated that multiple factors contribute to what type of treatment will

14

be best for different individuals and their families. For instance, if a caregiver objects to

the use of a treatment that may evoke more problematic behaviors, it may be best to

recommend the use of a treatment package consisting of a fading procedure.

Alternatively, if rapid results are the primary concern of caregivers and/or medical

professionals, then a function-based procedure without the use of fading could be the best

option.

Texture Fading

Texture fading is used to aid children in advancing from pureed or blended food

to solid table foods or more age-appropriate textures. Texture fading has been

implemented as part of treatment packages for food selectivity (Patel, Piazza, Santana,

&Volkert, 2002; Sharp & Jaquess, 2009; Shore, Babbitt, Williams, Coe, & Snyder, 1998)

and packing (Patel, Piazza, Layer, Coleman, & Swartzwelder, 2005). For instance, Shore

et al. (1998) evaluated a treatment package that consisted of texture fading,

reinforcement, and EE. The primary steps in the fading procedure were as follows: 100%

pureed, 100% junior, 100% ground, and 100% chopped fine, while some intermediate

textures were introduced for a couple of the participants. The treatment package used in

this study was successful in the treatment of food selectivity with all 4 children. That is,

by the end of the study all participants were consuming age-appropriate textures and

volume. Shore et al. discussed that in the absence of the fading component, the

reinforcement and extinction contingencies could have together contributed to results

observed for the participants. Thus, similar results may have been obtained without the

addition of the fading component in treatment. Nonetheless, fading was the likely

15

component responsible in reducing the amount of gags emitted by the participants given

that gagging was frequently observed when a higher texture was introduced without the

use of intermediate textures (e.g., going from puree immediately to chopped). In

addition, expulsions decreased for participants who initially displayed them prior to this

study. By using fading and gradually introducing more dense textures, participants may

have had more opportunities to learn the skills needed to control food within their mouth

than if there was an abrupt change in the type of food. Due to the incorporation of

differential reinforcement and EE, the contribution of the fading component could not be

clearly established.

In another study, Sharp and Jaquess (2009) found that a treatment package

consisting of EE, texture and bite fading, and non-contingent access to preferred items,

was effective in increasing the variety of foods consumed by a child diagnosed with

autism; however, the participant in this study still displayed deficits in eating appropriate

volumes and higher texture foods. EE was used to expand his variety by moving from

only consuming Pediasure presented by a syringe to consuming multiple pureed foods.

This participant was advanced to a wet ground texture during this treatment but not

beyond (i.e., the participant did not consume chopped texture as targeted for the terminal

criteria). There were high rates of gagging and refusal behaviors when ground texture

was introduced and the researchers went back to the wet ground. This may have been

due to inadequate oral motor skills. The researchers did state that they later increased to

ground by using smaller increments; however those data were not reported. Once again,

16

given that EE, as well as non-contingent reinforcement (NCR) were included treatment

components, the role of fading is not entirely clear.

Summary

The above findings have all demonstrated that fading procedures in the treatment

of feeding disorders are effective when combine with other treatment components. In an

effort to evaluate antecedent interventions in the treatment of food selectivity due to

consumer and professional concern many studies include antecedent components.

However, caregivers and other professionals are still apprehensive in the use of EE even

with the combination of antecedent procedures. Thus, it is necessary for the field to

evaluate all possible combinations of treatment procedures, both as packages and as

individual treatments.

Purpose of the Study

The present study aimed to evaluate various fading procedures without the use of

additional treatment components in an effort to expand the variety of foods or liquids

consumed by participants, by progressively increasing the amount of non-preferred foods

or liquids in their repertoire. It was presumed that fading procedures would decrease the

motivation to engage in food refusal behaviors when participants were presented with

non-preferred items. In many of the studies described previously, the contribution of the

fading component could not be clearly established because each of the treatment

packages utilized an EE procedure, which is known to increase consumption and

decrease problematic mealtime behaviors (e.g., Ahearn, 2002). The current study aimed

to replicate and extend the aforementioned studies on food selectivity by evaluating

17

fading procedures in the absence of other treatment components (e.g., backward

chaining) and without the initial introduction of differential reinforcement and EE.

Procedures similar to other research evaluating fading as a component of interventions

for individuals with feeding disorders (e.g., Luiselli et al.,2005; Mueller et al. 2004; Patel

et al., 2001; Shore et al., 1998) were replicated; however, this study used a sequential

introduction of treatment components by first introducing fading, then DRA, and finally

EE when necessary. The order of treatment components were introduced in a least to

most intrusive fashion.

18

Chapter 2

METHOD

Participants and Setting

Participants included 2 young boys, Bastion 4-years 3-months and Vincent 4years 7-months, both diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder and who exhibited

problems with feeding (i.e., food and/or liquid selectivity). Specifically, participants

were selected based upon their inadequate consumption of an age-appropriate variety of

food, display of problematic behaviors during mealtime (e.g., crying, disruption,

tantrums, aggression, self-injury, etc.), and particular to Bastion, the consumption of

atypical foods for his age (i.e., only liquid/puree). At the beginning of and throughout the

study participants were not diagnosed with any feeding related medical conditions such

as failure to thrive, and there were no medical concerns regarding their current weight.

The study was conducted at the Pediatric Behavior Research Lab at California State

University, Sacramento. Participants sat in a high-chair during all feeding sessions.

Prior to the study, Bastion only consumed a specifically prepared sweet tasting

liquid/puree mixture (with various items such as spinach, almond milk, apples, bananas)

from a bottle. Before participation in this study, Bastion had not received treatment

addressing his feeding problems besides an unsuccessful attempt to introduce cup

drinking by his private early intensive behavior treatment provider. Following a

procedure consisting of NCR and physical guidance to increase independent feeding

skills (i.e., eating from a spoon) with the main researcher, Bastion would eat a thickened

19

version (more consistent with a puree texture as opposed to liquid) of the preferred

mixture from a spoon, independently. Per parent report, before Bastion became even

more selective, he previously ate pureed bananas, apple sauce, and yogurt. Bastion

refused stage 3 baby foods when his mother tried to transition away from purees.

Following spoon training, Bastion’s mother was able to reintroduce pureed baby food

(Gerber jarred); however, Bastion continued to refuse any novel food of other textures or

different textures of preferred flavors. Thus, prior to treatment, Bastion was eating seven

types of pureed jar food (e.g., sweet potatoes, bananas, and pasta primavera), as well as

peach and banana-strawberry yogurt; however, he did not consume any solid/table-top

textures.

Previous to participating in this study, Vincent independently ate solid foods;

however, the variety and nutritional content was severely limited. His food repertoire

consisted of cheeseburgers from 3 specific fast-food restaurants, macaroni and cheese

from a specific restaurant, French fries from fast food restaurants, and some crunchy

snack foods (e.g., goldfish and pretzels). In addition, Vincent drank water regularly and

from any cup. Vincent had a history of discontinuing consumption of foods that were

previously consumed (e.g., pancakes, Pediasure, spaghetti, yogurt, apple sauce, and

fried rice).

Response Measurement and Data Collection

Data were taken on accepts, expulsions, gags, and whether the bite was consumed

(measured by mouth clean checks) per trial. An acceptance was defined as an entire bite

placed in the child’s mouth which completely passed the plane of the lips. Expulsions

20

were defined as a whole bite of food, which was previously accepted, leaving the plane of

the child’s lips. A swallow or mouth clean was defined as the child’s mouth containing a

piece of food no larger than the size of a pea, given that expulsion did not occur. The

experimenter conducted mouth clean checks 15-s after the bite was placed in the

participant’s mouth and thereafter every 10-s if the participant did not swallow the food

or refused to open their mouth.

Instances of inappropriate mealtime behaviors were collected on a trial-by-trial

basis. Inappropriate mealtime behaviors were divided into groups depending on the

topography of each participant’s problematic behaviors, which included aggression (e.g.,

biting and hitting), negative vocalizations (e.g., screaming), disruptive behaviors (e.g.,

pushing the spoon/experimenter’s hand away and crushing the cup), self-injury (e.g.,

biting any part of his body), and biting objects (e.g., the back of the high chair), for

Vincent. Bastion engaged in two topographies of refusal behaviors, negative

vocalizations (e.g., crying) and disruption (e.g., pushing the spoon away). For each trial,

when any of the behaviors within a certain group were observed, it was recorded as one

instance. The exact frequency of inappropriate behaviors were not counted, only whether

or not any behaviors within a group occurred during the trial. All responses were

recorded using pen/pencil and paper with data sheets specifically prepared for this study

(see Appendix).

Data were reported as percentage of bites consumed without expulsion for each

10 trial session. Data were taken per trial across four topographies which included:

accept, expulsion, gag, and whether a swallow occurred (i.e., mouth clean). Percentage

21

occurrence for the dependent variable was calculated by dividing the total number of

bites consumed without expulsions by the total number of trials (i.e., 10) and then

multiplying by 100. In addition, the percentage of trials with inappropriate mealtime

behavior was obtained by using the same formula.

Interobserver Agreement and Treatment Integrity

Interobserver agreement data were collected across treatment components, as well

as fading steps throughout the study with a second observer present during the session or

via video recording. A second independent observer collected data on all dependent

measures and interobserver agreement was calculated for accepts, expulsions, mouth

cleans, gags and inappropriate mealtime behaviors. Data were collected by a second

observer during 82% of banana sessions and 70% of sweet potato sessions for Bastion, as

well as recorded during 67% of Pediasure sessions and 46% of rice sessions for

Vincent. Interobserver agreement for measures related to consumption (e.g., accepts,

mouth cleans, etc) and inappropriate mealtime behaviors was calculated using the pointby-point agreement method. That is, each trial must have been scored by both observers

marking either a plus or minus for each dependent variable in order for that trial to be

scored as an agreement. A percentage for interobserver agreement was obtained by

dividing the total number of agreements for each dependent measure by the total number

of trials per session (i.e., 10) and multiplied by 100. Interobserver agreement for

acceptance, expulsion, mouth clean, and gagging was 100% during banana and sweet

potato sessions for Bastion with one exception for gagging during sweet potato sessions

which resulted in 99.79% (range 90-100%) agreement. Interobserver agreement for

22

inappropriate mealtime behaviors during Bastion’s banana and sweet potato sessions

were 97.69% (range 70-100%) and 97.45% (range 70-100%) for negative vocalizations,

respectively, and 99.85% (range 90-100%) and 99.79% (90-100%) for disruptions,

respectively. Interobserver agreement for acceptance, expulsion, and gagging was 100%

during all sessions (i.e., Pediasure and rice) for Vincent. In addition, interobserver

agreement for mouth clean was 99.72% (range 90-100%) for Pediasure and 100% for

rice. Interobserver agreement data for all topographies of inappropriate mealtime

behaviors, excluding negative vocalizations and disruption, during Vincent’s sessions

was 100%. During Pediasure sessions, interobserver agreement was 98.82% (range 80100%) for negative vocalizations and 99.19% (range 90-100) for disruptions; during rice

sessions, interobserver agreement was 97.33% (range 80-100%) for negative

vocalizations and 100% for disruptions.

Researchers gathered treatment integrity data across varying treatment

components (i.e., baseline, fading, and DRA) during the course of the study. Treatment

integrity was evaluated for bite presentation (i.e., pre-scooped and placed in front of the

participant), prompting, termination of trials for expulsions and refusal behaviors, mouth

clean checks, and consequences for swallows (i.e., praise only during fading and praise

plus delivery of item during DRA). For Bastion, data were gathered during 63% of

banana sessions and 51% of sweet potato sessions. Treatment integrity during Bastion’s

sessions was 100% for both foods with a few exceptions. For instance, mouth clean

checks were implemented with 99.80% (range 90-100%) and 99.41% (range 90-100%)

23

integrity for banana and sweet potato, respectively. Treatment integrity for trial

termination due to refusal behaviors during sweet potato sessions was 99.41% (80100%). Finally, praise was provided with 99.60% (90-100%) and 99.41% (90-100%)

integrity for banana and sweet potato sessions, respectively. For Vincent, data were

collected during 64% of Pediasure sessions and 66% of rice sessions. Treatment

integrity during Vincent’s sessions was 100% for both foods, except for mouth clean

checks during Pediasure which was implemented with 99.41% (range 90-100%)

integrity.

24

Food Preparation

In order to ensure consistency in food preparation, the main researcher prepared

the food during all sessions by referring to predetermined fading criteria and written

directions (see Tables 1-3 below).

Table 1

Fading steps: Liquid

Main and Intermediate Fading Steps Preparation Instructions for Liquid Selectivity

Liquid Fading

(Flavor-Flavor)

Step 1

Preparation Directions

100ml preferred liquid

95ml preferred/5ml non-preferred

Step 2

90ml preferred/10ml non-preferred

Intermediate

85ml preferred/15ml non-preferred

Step 2

80ml preferred liquid/20ml non-preferred liquid

1.

75ml preferred/25ml non-preferred

Step 3

2.

70ml preferred/30ml non-preferred

Intermediate

3.

65ml preferred/35ml non-preferred

Step 3

60ml preferred liquid/40ml non-preferred liquid

1.

55ml preferred/45ml non-preferred

Step 4

2.

50ml preferred/50ml non-preferred

Intermediate

3.

45ml preferred/55ml non-preferred

Step 4

40ml preferred liquid/60ml non-preferred liquid

1.

35ml preferred/65ml non-preferred

Step 5

2.

30ml preferred/70ml non-preferred

Intermediate

3.

25ml preferred/75ml non-preferred

Step 5

10ml preferred liquid/80ml non-preferred liquid

1.

15ml preferred/ 85ml non-preferred

Step 6

2.

10ml preferred/ 90ml non-preferred

Intermediate

3.

5ml preferred/ 95ml non-preferred

Step 6

100ml non-preferred liquid

Note: Target items used for Vincent with this fading sequence (liquid blending) were

1.

2.

3.

Pediasure (non-preferred) and water (preferred).

25

Table 2

Fading steps: Texture

Main and Intermediate Fading Steps Preparation Instructions for Texture Selectivity

Texture Fading

Step 1

Puree

Step 2

Intermediate

Step 2

Wet Ground

Step 3

Intermediate

Step 3

Ground

Step 4

Intermediate

Step 4

Finely Chopped

Step 5

Intermediate

Preparation Directions

Puree: Equal parts water and food item blended in a blender until

smooth (also, pre-packaged/jarred).

1.

90g puree/15ml water & 30g ground size

2.

60g puree/30ml water & 60g ground size

3.

30g puree/45ml water & 90g ground size

Cut with an electric food chopper into pieces the size of a ½

grain of rice and combined with 15 ml water per 30g of food

1.

11.25ml water/30g ground size

2.

7.5ml water/30g ground size

3.

3.75ml water/30g ground size

Cut with an electric food chopper into pieces the size of ½ grain

of rice

1.

75g ground/25g finely chopped

2.

50g ground/50g finely chopped

3.

25g ground/75g finely chopped

Less than ¼ inch with food chopper or sharp knife (extra small

piece)

1.

75g finely chopped /25g chopped

2.

50g finely chopped/50g chopped

3.

25g finely chopped /75g chopped

Step 5

Chopped

About ½ inch by ¼ inch with natural thickness (small piece)

¼ of final size

½ of final size

¾ of final size

Step 6 (final)

About 1 inch by 1 inch with ¼ inch slice or natural thickness

Table Top

(large piece or typical presentation)

Note: Target foods used for Bastion with this fading sequence were banana and sweet

Step 6

Intermediate

1.

2.

3.

potato (preferred as puree form).

26

Table 3

Fading steps: Demand (Bolus size)

Main and Intermediate Fading Steps Preparation Instructions for General Selectivity

Demand Fading

(Bolus Size)

Preparation Directions

½ piece

1 piece

2 pieces

Step 1

3 pieces

1.

4 pieces

Step 2

2.

5 pieces

Intermediate

3.

6 pieces

Step 2

7 pieces

1.

8 pieces

Step 3

2.

9 pieces

Intermediate

3.

10 pieces

Step 3

11 pieces

1.

12 pieces

Step 4

2.

13 pieces

Intermediate

3.

14 pieces

Step 4

15 pieces

1.

16 pieces

Step 5

2.

17 pieces

Intermediate

3.

18 pieces

Step 5

19 pieces

1.

20 pieces

Step 6

2.

21 pieces

Intermediate

3.

22 pieces

Step 6

23 pieces

Note: This fading sequence is used when introducing new and/or non-preferred foods by

Step 1

Intermediate

1.

2.

3.

themselves (i.e., without blending). Target food used for Vincent with this fading

sequence was rice (non-preferred).

27

Experimental Design

A multiple probe design across foods with probes prior to the introduction of a

new fading step was utilized to demonstrate experimental control and control for

additional, unnecessary exposure to the target food introduced in the second tier of the

design. The intervention in each baseline/tier was introduced in a staggered fashion and

was introduced when responding in each baseline was stable. Probes were introduced for

the next fading step and final target food/liquid prior to moving to the next step in the

fading procedure. When probes were required for the first targeted food, prior to the

introduction of the second food into treatment, probes were also conducted for the second

tier food. In addition, probes and sessions for each tier food were conducted in a

concurrent fashion. Each treatment component was introduced in a sequential fashion:

first fading with praise only, then fading plus DRA (praise and tangible or edible), and

finally, fading plus DRA and EE (however, EE was not needed for either participant in

this study).

Assessments

For the current study, food items that were preferred or consumed prior to

participation in research were used as the initial fading step for Bastion (both tier 1 and 2

foods) and Vincent (tier 1 food only) in order to better ensure consumption, lower the

chance for the occurrence of maladaptive behaviors, and facilitate success during

conditions that did not involve a DRA or EE component. Preferred food items were used

because participants were expected to self-feed and no physical prompts (with the

exception of Vincent who required assistance with spoon-feeding as to not spill the

28

liquid) or EE were implemented during the first two treatment components. In order to

determine preferred foods to be targeted for treatment, paired-choice preference

assessments were conducted prior to starting treatment, using procedures described by

Fisher, Piazza, Bowman, Hagopian, Owens, and Slevin (1992). Paired-choice preference

assessments included foods or liquids that the child consumed prior to the start of the

study. The foods used in the study were selected based upon consumption during the

preference assessment, as well as parent priority, and ease of use with a fading

(specifically, food blending) procedure.

In addition, a pre and post paired-choice preference assessment (Fisher et al.,

1992) was used for one participant to evaluate consumption of the final target foods or

liquids. This assessment was used in order to demonstrate whether following treatment

implemented with two non-preferred foods, results would generalize to foods not targeted

during treatment. Foods that were targeted during treatment were included in the prepost assessment, as well as foods not targeted during treatment.

Lastly, in order to determine appropriate items to be used during the DRA

component, a third paired-choice preference assessment (Fisher et al., 1992) was

completed prior to the introduction of differential reinforcement for the participants who

necessitated the DRA component (i.e., Vincent). This assessment included tangible items

that were identified by parents as being highly preferred. For the top three items

identified as preferred from this preference assessment, a reinforcer assessment was

conducted to determine if the items functioned as reinforcement for Vincent’s behavior.

The response used for Vincent during the first reinforcer assessment (when DRA was

29

determined to be necessary for Pediasure) was drinking water from a cup (a skill he

demonstrated on his own terms, however, inconsistent consumption of water was

observed during treatment sessions) and when the DRA component was added to the

treatment package addressing the refusal of rice, a second reinforcer assessment was

conducted where the response of drinking Pediasure was evaluated. A progressive ratio

schedule was used to identify the breaking point for each preferred item similar to the

procedures described by Roane, Lerman, and Vorndran (2001). That is, the response

requirement increased by one as the previous requirement was met. In order to control

for ratio strain during the reinforcer assessment, each progressive ratio schedule was

implemented twice before increasing the reinforcement schedule. When the participant

stopped responding for three consecutive minutes, the reinforcer assessment for that item

was terminated. For Vincent, three items were identified and used as reinforcement

during the first tier food (i.e., Pediasure) during the implementation of the DRA

treatment component. Items included a caterpillar game, shooting ice-cream cone, and a

sound train puzzle. The three new items that were identified via preference and

reinforcer assessments to use for the DRA component for the second tier food (i.e., rice)

were a child piano, sound farm animal puzzle, and a ball spinner. Brief preference

assessments were conducted at the beginning of each session and within a session if

refusal behaviors were observed or other behavioral antecedents (e.g., not playing with

the item on the previous trial, increase in stereotypical behavior, and a decrease in

attending behaviors) suggesting habituation to that item were observed.

30

Procedures

Criteria for Phase and Component Advancement

Probes were conducted for the next step and final target form prior to moving to

the next phase in the fading procedure. At any point when participants met the criterion

of 80% or better consumption of the final target form during probe sessions, the final

target form was introduced with the current treatment component. Participants were

required to consume at least 80% of bites during a next step probe session in order for the

next step to be introduced in treatment. If participants consumed less than 80% of bites

during a next step probe session, then the intermediate fading sequence was introduced.

If following the introduction of the intermediate fading sequence the participant

consumed less than 80% of bites for 3 consecutive sessions, then the next treatment

component (i.e., fading plus DRA and fading plus DRA plus EE) was introduced. If

participants met criteria for advancement to the next step and then during that phase the

percentage of bites consumed fell below 80% for 3 consecutive sessions, then the

intermediate fading sequence was introduced. Mastery criteria for any phase during

treatment were 3 consecutive sessions with bites consumed at 90% or better. If gags

occurred more than 20% during a session, then that session was not counted in the

criterion (3 consecutive sessions) to advance fading steps. That is, gags must have fallen

below 20% for the participant to move forward in treatment phases.

Baseline

Baseline probe sessions were used to determine the step at which to begin fading.

During baseline sessions 10 presentations (trials) of each main fading step were assessed.

31

For the food item introduced in the second tier of the design, probe sessions were

conducted periodically so that the participant was not exposed to an unnecessary amount

of sessions with the food not currently targeted. The researcher issued a vocal prompt

stating that it is time to eat and placed a bite in front of the participant or held the bite in

front of the child’s mouth. No programmed consequences were in place for accepted

bites. If participants accepted and swallowed any bite, then praise (e.g., “Nice eating,”

“Awesome,” “You’re fantastic,” etc) was provided. Escape was allowed (i.e., removal of

the bite/termination of the trial) if the participant said “no,” pushed the food away,

engaged in other inappropriate mealtime behaviors, or after 15-s had elapsed (whichever

occurred first).

Treatment

General Procedures. Food preparation and fading procedures varied depending

upon the type of target foods and fading procedures (e.g., texture, liquid, etc.) necessary

for each participant (See tables 1-3 above for each type of fading preparation). For

instance, when texture fading was used then the fading sequence steps were measured

based upon the viscosity of the food (e.g., puree, wet ground, ground, etc.) and when

liquid fading was used then the measurement was based upon milliliters. Each fading

step increased by 20% increments, thus there was a total of 6 main fading steps (i.e., 0%

[currently accepted form], 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100% [final form]). If the main

fading increments were not successful, then an intermediate fading procedure was

implemented prior to advancing treatment components. Intermediate fading steps

consisted of the following sequence: 1) 75% previously successful step/25% next step, 2)

32

50% previously successful step/50% next step, 3) 25% previously successful step/75%

next step, 4) 100% next step.

For each trial, the therapist prepared a pre-scooped bite of food and placed the

bite in front of the participant or presented the bite in front of their mouth. The prescooped bite was used to maintain a consistent bite size and consistent amount of food

being presented across sessions. Bite sizes varied between participants depending upon

the child’s current skill level. A gestural prompt or vocal prompt to “take a bite” or “eat

your food” was given after 15-s without independent initiation of self-feeding or failure

to open their mouth following the presentation of the bite for each trial. Following bite

acceptance and given that an expulsion did not occur, mouth clean checks were

conducted 15-s after a bite was accepted. When there was food in the participant’s mouth

following a check, then the experimenter vocally prompted the child to swallow and

continued to check for mouth clean every 10-s. A mouth clean check consisted of the

researcher saying, “Show me that the food is gone” or a similar statement only once and

no physical prompts were provided. If an expulsion occurred, then the trial was

terminated and recorded as a minus for consumption or mouth clean, unless the

participant independently initiated another acceptance and/or responded to a

vocal/gestural prompt to finish the bite. During the fading or fading plus DRA

conditions, when the child refused to take a bite by vocally stating “no,” engaged in any

other refusal behaviors (e.g., disruption), or did not respond by taking a bite after 15-s of

the bite presentation, then the trial was recorded as a minus and the bite was represented

33

as a new trial (with the exception of Bastion, an additional vocal/gestural prompt was

used). Each subsequent refusal was consequated in the same manner.

Fading with praise only. This condition began by presenting food/liquid that

was currently consumed with minimal to no inappropriate mealtime behaviors by

participants (i.e., participants’ preferred food/liquid). During this condition the therapist

gave prompts as described above (in “treatment” section) and provided praise contingent

on food consumption. After 3 consecutive meals with 90% consumption without

expulsions and gags (below 20%), the next fading step was introduced. Phase

advancement criteria and criteria to move backwards (i.e., to intermediate fading steps or

introduction of more intrusive treatment components) was followed as outlined above.

Both the next fading step and final target item probes were conducted before moving to

the next fading step. If there were 3 consecutive meals where consumption was below

80% after the intermediate fading phase sequence had been presented, then the

participant moved to fading plus DRA.

Fading plus DRA. Procedures in this condition were identical to fading with

praise except that the participant received praise and a preferred tangible or edible

contingent on each bite consumed. When this component was introduced, an additional

paired-stimulus preference assessment and a reinforcer assessment were conducted to

determine preferred items to be used as reinforcement. Criteria for fading step

advancement was followed as outlined above. If there were 3 consecutive meals where

consumption was below 80% after the intermediate fading sequence had been presented,

then the participant moved to fading plus DRA and EE. However, it should be noted that

34

EE was not necessary for either participant; had EE been necessary, it would have been

implemented following the procedures described below.

Fading plus DRA and EE. In this final condition, procedures would have been

identical to fading plus DRA except EE in the form of a non-removal of the spoon (NRS)

procedure would be added. Prior to implementing the NRS procedure, the therapist

would place a pre-scooped bite in front of the participant and vocally instruct the

participant to eat the food. If the participant did not pick up the spoon and place the bite

in their mouth within 5-s of the spoon presentation, then the therapist would provide a

gesture and another vocal instruction to eat the food. Once again, if the participant did

not respond within 5-s, the therapist would implement NRS, during which a bite on a

spoon would be within 1 inch of the participant’s mouth, following the mouth if head

turns or other disruptions occurred. The therapist would insert the bite into the

participant’s mouth when the opportunity arose (i.e., participant independently opens

their mouth). Criteria for fading advancement would be followed as outlined above.

35

Chapter 3

RESULTS

Assessments

Preference Assessments

For Bastion, two paired-choice preference assessments were conducted with

jarred purees reported by his mother to be preferred and results are displayed in Figure 1.

The assessment included banana, banana-strawberry yogurt, lasagna, chicken noodle,

pasta primavera, peach yogurt, sweet potatoes, herb chicken, mixed veggies with chicken,

and apple sauce. All purees, except apple sauce, were selected during both assessments;

however, only five (banana, lasagna, pasta primavera, sweet potato, and herb chicken) of

the ten foods presented in the first assessment were assessed again in an attempt to

remove the more difficult puree mixtures to fade by texture. Banana and sweet potato

were chosen as the target foods based upon consumption during preference assessments,

parent preference, and feasibility to use with the texture fading procedure.

Results from Bastion’s pre- and post-treatment paired-choice preference

assessment are presented in Figure 2. The pre- and post-treatment assessments were

conducted with the final (table-top) form of the target foods (i.e., banana and sweet

potato). During the preference assessment conducted prior to treatment implementation,

Bastion did not consume any of the foods presented as the final form, although during the

same assessment conducted following completion of the study, Bastion consumed both

target foods, but none of the non-targeted foods. It should be noted that only the puree

36

form of one of the foods (i.e., apple) presented at a table-top texture was ever consumed

as a puree. Bastion consumed apple sauce prior to and throughout the study. These data

show that generalization to novel table-top foods and table-top foods that were consumed

in a different form (i.e., puree) did not occur.

Cheeseburger, macaroni and cheese, French fries, goldfish, Cheez-its and water

were evaluated for Vincent’s preferred foods assessment (see Figure 3). Water was the

most preferred, followed by cheeseburger and macaroni and cheese. Vincent never

selected the French fries, goldfish, or Cheez-its. In addition to water being selected

most frequently, Vincent requested for water during the preference assessment when

other items were presented as options and after the assessment was completed.

100

90

Precent Selected

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Figure 1. Bastion paired-choice preference assessment (purees). Percentage of trials

with consumption during two paired-choice preference assessments prior to treatment.

37

100

90

80

Percent Selected

70

60

50

40

Pre

30

20

Post

10

0

Figure 2. Bastion pre/post paired-choice preference assessment (final form). Percentage

of trials with consumption during assessments of table-top textures.

100

90

Percent Chosen

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Figure 3. Vincent paired-choice preference assessment (preferred foods). Percentage of

trials with consumption during the preference assessment prior to treatment.

38

Reinforcer Assessment for DRA Component (Vincent Only)

The first paired-choice preference assessment (see Figure 4) included eight

tangible items (toys) as follows: ice-cream cone (shooting), bee book, dog book (with

interactive stuffed dog), caterpillar game, spinning top, sound train puzzle, butterfly in a

jar, and a gerbil in a ball. The top three items were caterpillar, train puzzle, and icecream cone. Results from the reinforcer assessment (see Figure 5) demonstrated that all

items selected during the preference assessment functioned as reinforcement for Vincent

with the breaking points at PR-9 (train puzzle), PR-8 (caterpillar game), and PR-3 (icecream cone). All toys were selected during brief preference assessments during sessions

and used throughout the DRA treatment component when Pediasure was the target.

100

90

Percent Chosen

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Figure 4. Vincent paired-choice preference assessment (Toys #1). Preference

assessment for toys to use as reinforcement during the DRA component for Pediasure.

39

100

90

80

Frequency

70

60

50

Amount of PRItem

Break

Presentatins

Total # of

Trials

40

30

20

10

0

Train Puzzle

Caterpillar

Ice-Cream cone

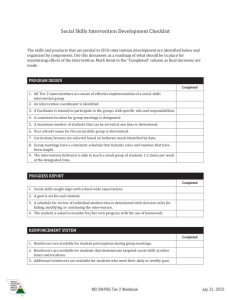

Figure 5. Vincent reinforcer assessment (Toys #1). Reinforcer assessment for toys used

as reinforcement during the DRA component for Pediasure.

The second paired-choice preference assessment (see Figure 6) included 10

tangible items (toys) as follows: ice-cream cone (shooting), guitar, llama book, caterpillar

game, hula girl, sound train puzzle, sound farm animal puzzle, ball spinner, child piano,

and wind-up dog. The top three items from the preference assessment were piano, animal

puzzle, and ball spinner. Results from the subsequent reinforcer assessment (see Figure

7) demonstrated that all items selected during the preference assessment functioned as

reinforcement for Vincent with the breaking points at PR-8 (piano), PR-6 (animal

puzzle), and PR-5 (ball spinner). All toys were selected during brief preference

assessments throughout sessions and used during the DRA treatment component when

rice was the target.

40

Percet Chosen

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Figure 6. Vincent paired-choice preference assessment (Toys #2). Preference

assessment for toys to use as reinforcement during the DRA component for fried rice.

70

60

Frequency

50

Total # of

Trials

40

Amount of

Item

Presentations

PRBreak

30

20

10

0

Piano

Animal Puzzle

Ball Spinner

Figure 7. Vincent reinforcer assessment (Toys #2). Reinforcer assessment for toys used

as reinforcement during the DRA component for fried rice.

41

Treatment

The percentage of bites consumed without expulsion per session for Bastion and

Vincent are displayed in Figures 8 and 10, respectively. Data for both target foods are

presented in a multiple baseline format across foods. During baseline, Bastion did not

accept or consume any bites of his preferred foods/flavors when presented as nonpuree/unfamiliar textures; however, he did consume all 10 bites of both target foods

presented as the preferred/familiar texture (i.e., pureed/jarred food). Pureed sweet

potatoes were not introduced in treatment until session 33 when the intermediate

sequence for step 4 was also introduced for banana. Furthermore, when banana was the

only target food in treatment, as well as after sweet potato was introduced in treatment,

probes were conducted concurrently for sweet potato and banana throughout the study.

All sweet potato probes conducted prior to intervention remained at 0% consumption

until texture fading was introduced with sweet potato.

Bastion’s results observed for banana (see Figure 8) will be discussed first. When

pureed banana (i.e., step 1) was introduced as the beginning texture in the texture fading

sequence, Bastion consumed 100% of banana bites for three consecutive sessions.

During the first two probe sessions for banana during the fading only component, Bastion

consumed 100% of step 2 bites (i.e., wet ground) and refused all step 6 bites (i.e., final

step/table-top form), however, he did accept and expel one bite of step 6. Consequently,

step 2 of the fading sequence was introduced and criteria for advancement from step 2

were met after five sessions. For the second set of probe sessions, Bastion did not meet

criteria to move onto main fading steps 3 (30% of bites consumed) or 6 (no bites

42

consumed), thus the phase 3 intermediate steps (mixture of ground/wet ground textures)

were introduced as the next step in the fading progressions. Following the introduction

of the intermediate fading sequence for step 3, Bastion immediately consumed all bites

for three consecutive sessions across all intermediate steps and the main step for fading

step 3 (i.e., ground). All bites during steps 4 and 6 probe sessions were refused and the

intermediate sequence for step 4 was introduced. Similar to step 3 intermediate steps, the

step 4 intermediate sequence was effective in increasing bites consumed to 100% and

transitioning to main fading step 4. The same results occurred for steps 5 and 6, in which

the intermediate phase was necessary and effective in increasing consumption of

previously rejected textures. It is worth noting that during the fourth and fifth set of

probes, Bastion consumed 20% and 30% of bites for the next step probes (i.e., steps 5 and

6), respectively, thus not meeting criteria for the main steps to be introduced without first

introducing the intermediate steps, however, demonstrating an increase in consumption

during probes.

Corresponding to results observed for Bastion with banana, the fading only

treatment component was successful in increasing consumption of previously rejected

textures for sweet potato. Prior to the introduction of treatment, all baseline and probe

sessions for sweet potato remained at 0% consumption except for step 1 (i.e., puree)

during which all bites were consumed. Since step 1 was consumed during baseline, it

was introduced as the first fading phase during treatment and all bites presented were

consumed for 5 sessions. Probes following successful sessions for fading step 1 did not

meet mastery criteria for introduction of main fading step 2, thus the intermediate

Figure 8. Bastion percentage of bites consumed without expulsions. Results for banana (tier 1) and sweet potato (tier 2) during

texture fading. Closed data points indicate main fading steps and open data points indicate intermediate fading steps.

43

44

sequence for step 2 was introduced as the next fading progression. Responding was

variable for the first 3 sessions of the step 2 intermediate sequence phase 1 which

increased and stabilized over the following 3 sessions. Step 2 intermediate phase 2 was