Chapter 10

advertisement

T10.1 Chapter Outline

Chapter 10

Making Capital Investment Decisions

Chapter Organization

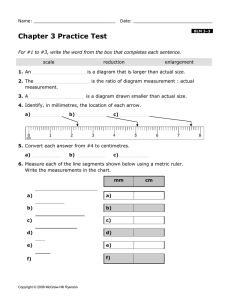

Project Cash Flows: A First Look

Incremental Cash Flows

Pro Forma Financial Statements and Project

Cash Flows

More on Project Cash Flow

Alternative Definitions of Operating Cash Flow

Some Special Cases of Discounted Cash

Flow Analysis

CLICK MOUSE OR HIT

SPACEBAR TO ADVANCE

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd.

T10.2 Fundamental Principles of Project Evaluation

Fundamental Principles of Project Evaluation:

Project evaluation - the application of one or more capital

budgeting decision rules to estimated relevant project cash

flows in order to make the investment decision.

Relevant cash flows - the incremental cash flows associated with

the decision to invest in a project.

The incremental cash flows for project evaluation consist

of any and all changes in the firm’s future cash flows that

are a direct consequence of taking the project.

Stand-alone principle - evaluation of a project based on the

project’s incremental cash flows.

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 2

T10.3 Incremental Cash Flows

Terminology

Key issue:

When

is a cash flow

incremental?

A. Sunk costs

B. Opportunity costs

C. Side effects

D. Net working capital

E. Financing costs

F. Inflation

G. Government Intervention

H. Other issues

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 3

Incremental Cash Flows

Sunk Cost - a cost that has already been incurred, cannot be

removed and therefore should not be considered in the

investment decision - the ‘firm has to pay this cost no matter

what’

example in the oil & gas business is the exploration costs incurred

in finding reserves - these are sunk costs and should not be

considered in any evaluation of developing those reserves

Opportunity Costs ‘ the most valuable alternative that is given

up if a particular investment is undertaken’ - if a project results

in an opportunity being forgone this benefit that has been given

up should be included in the project cash flow as a cost - see

the text example

Side Effects - ‘erosion’ - cash flows of a new project that come

at the expense of a firm’s existing projects – these ‘negative’

cash flows should be included

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 4

Incremental Cash Flows

Net Working Capital - projects often require investment in

working capital in addition to the investment in longer term

assets e.g. Investment in inventories & receivables. Important

to build in the recovery of this cash investment at the end of the

project.

Financing Costs - are not included. The financing of the project

is a separate decision - we want to evallate the cash flows

generated by the assets from the project.

Inflation - a factor in projects with longer lives. Cash flows

should factor in inflation just as the nominal discount rate

includes inflation premiums. An alternative approach is to use

a ‘real;’ or inflation adjusted discount rate and calculate future

‘real’ cash flows - adjusted for inflation (inflation element

removed)

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 5

Incremental Cash Flows

Government Intervention - where government incentives result

in incremental cash flow - they should be incorporated into the

project cash flow e.g. Grants, tax credits, subsidized loans, etc.

Other - after tax incremental cash flow (not after tax earnings!)

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 6

Pro Forma Financial Statements & Project Cash Flows – the mechanics

Projecting the future years operations of the project in the form

o f pro forma financial statements summarize the relevant

project information – these pro forma statements can then be

used to project the cash flows

projected income statement - enable the projection of operating

cash flows

projected balance sheet or balance sheet extracts - enable the

projection of working capital and capital spending

Project cash flows – use the Cash Flow From Assets model

(similar to ‘mini-firm’ cash flow) in establishing the incremental

cash flow from the project

operating cash flow

net working capital requirements

capital spending

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 7

NPV - Incremental Well Case

CAPEX

Year

2002

Net of Royalties

at 20%

Fixed Well

Costs

Variable

Costs

Total Well

Costs

Net Cash

Flow

434940

324220

267000

224280

192240

160200

145340

125730

105120

95440

85260

74580

63400

52720

52720

347952

259376

213600

179424

153792

128160

116272

100584

84096

76352

68208

59664

50720

42176

42176

30000

30000

30000

31000

31500

32000

32000

32500

33000

33500

34000

34500

35500

36000

36500

52500

48000

38000

30000

24000

18500

14500

10000

7500

5000

3000

3000

3000

3000

3000

82500

78000

68000

61000

55500

50500

46500

42500

40500

38500

37000

37500

38500

39000

39500

-300,000

265452

181376

145600

118424

98292

77660

69772

58084

43596

37852

31208

22164

12220

3176

2676

2403190

1922552

-300,000

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

Total

Incremental Price

WI @50%WI Revenues

Production$Cdn/bbl

$

m bbls

m bbls

33

29

25

21

18

15

13

11

9

8

7

6

5

4

4

-300,000

26.36

22.36

21.36

21.36

21.36

21.36

22.36

22.86

23.36

23.86

24.36

24.86

25.36

26.36

26.36

208

16.5

14.5

12.5

10.5

9

7.5

6.5

5.5

4.5

4

3.5

3

2.5

2

2

104

492000

NPV at 15%

NPV at 10%

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

263000

$394,442.02

$505,363.01

Slide 8

755000

116755

T10.4 Example: Preparing Pro Forma Statements

Suppose we want to prepare a set of pro forma financial statements

for a project for ABC Co. In order to do so, we must have some

background information. In this case, assume:

1. Sales of 10,000 units/year @ $5/unit.

2. Variable cost per unit is $3. Fixed costs are $5,000 per year.

The project has no salvage value. Project life is 3 years.

3. Project cost is $21,000. Depreciation is $7,000/year.

4. Additional net working capital is $10,000.

5. The firm’s required return is 20%. The tax rate is 34%.

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 9

T10.4 Example: Preparing Pro Forma Statements (continued)

Pro Forma Financial Statements

Projected Income Statements

Sales

Var. costs

$______

______

$20,000

Fixed costs

5,000

Depreciation

7,000

EBIT

Taxes (34%)

Net income

$______

2,720

$______

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 10

T10.4 Example: Preparing Pro Forma Statements (continued)

Pro Forma Financial Statements

Projected Income Statements

Sales

Var. costs

$50,000

30,000

$20,000

Fixed costs

5,000

Depreciation

7,000

EBIT

Taxes (34%)

Net income

$ 8,000

2,720

$ 5,280

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 11

T10.4 Example: Preparing Pro Forma Statements (concluded)

Projected Balance Sheets

0

1

2

3

$______

$10,000

$10,000

$10,000

NFA

21,000

______

______

0

Total

$31,000

$24,000

$17,000

$10,000

NWC

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 12

T10.4 Example: Preparing Pro Forma Statements (concluded)

Projected Balance Sheets

0

1

2

3

NWC

$10,000

$10,000

$10,000

$10,000

NFA

21,000

14,000

7,000

0

Total

$31,000

$24,000

$17,000

$10,000

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 13

T10.5 Example: Using Pro Formas for Project Evaluation

Now let’s use the information from the previous example to do

a capital budgeting analysis.

Project operating cash flow (OCF):

EBIT

$8,000

Depreciation

+7,000

Taxes

-2,720

OCF

$12,280

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 14

T10.5 Example: Using Pro Formas for Project Evaluation (continued)

Project Cash Flows

0

OCF

Chg. NWC

______

Cap. Sp.

-21,000

Total

______

1

2

3

$12,280

$12,280

$12,280

______

$12,280

$12,280

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

$______

Slide 15

T10.5 Example: Using Pro Formas for Project Evaluation (continued)

Project Cash Flows

0

OCF

Chg. NWC

-10,000

Cap. Sp.

-21,000

Total

-31,000

1

2

3

$12,280

$12,280

$12,280

10,000

$12,280

$12,280

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

$22,280

Slide 16

T10.5 Example: Using Pro Formas for Project Evaluation (concluded)

Capital Budgeting Evaluation:

NPV

=

=

-$31,000 + $12,280/1.201 + $12,280/1.20 2 + $22,280/1.20 3

$655

IRR

=

21%

PBP

=

2.3 years

AAR

=

$5280/{(31,000 + 24,000 + 17,000 + 10,000)/4} = 25.76%

Should the firm invest in this project?

Yes -- the NPV > 0, and the IRR > required return

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 17

Example: Estimating Changes in Net Working Capital

In estimating cash flows we must account for the fact that some of the incremental

sales associated with a project will be on credit, and that some costs won’t be paid

at the time of investment.

Estimate changes in NWC. Assume:

1.

2.

Fixed asset spending is zero.

The change in net working capital spending is $200:

0

1

Change

A/R

$100

$200

+100

___

INV

100

150

+50

___

-A/P

100

50

(50)

___

NWC

$100

$300

Chg. NWC = $_____

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 18

Example: Estimating Changes in Net Working Capital

In estimating cash flows we must account for the fact that some of the incremental

sales associated with a project will be on credit, and that some costs won’t be paid

at the time of investment. How?

Answer: Estimate changes in NWC. Assume:

1.

2.

Fixed asset spending is zero.

The change in net working capital spending is $200:

0

1

Change

A/R

$100

$200

+100

INV

100

150

+50

-A/P

100

50

(50)

NWC

$100

$300

Chg. NWC = $200

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 19

Example: Estimating Changes in Net Working Capital (continued)

Now, estimate operating and total cash flow:

Sales

$300

Costs

200

Depreciation

EBIT

Tax

0

$100

0

Net Income

$100

OCF = EBIT + Dep. Taxes = $100

Total Cash flow = OCF Change in NWC Capital Spending

= $100 ______ ______ = ______

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 20

Example: Estimating Changes in Net Working Capital (continued)

Now, estimate operating and total cash flow:

Sales

$300

Costs

200

Depreciation

EBIT

Tax

0

$100

0

Net Income

$100

OCF = EBIT + Dep. Taxes = $100

Total Cash flow = OCF Change in NWC Capital Spending

= $100 200

0

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

= $100

Slide 21

Example: Estimating Changes in Net Working Capital (concluded)

Where did the - $100 in total cash flow come from?

What really happened:

Cash sales

= $300 - ____

= $200 (collections)

Cash costs

= $200 + ____ + ____ = $300 (disbursements)

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 22

Example: Estimating Changes in Net Working Capital (concluded)

Where did the - $100 in total cash flow come from?

What really happened:

Cash sales

= $300 - 100

= $200 (collections)

Cash costs

= $200 + 50 + 50 = $300 (disbursements)

Cash flow

= $200 - 300 = - $100 (= cash in cash out)

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 23

CCA Property Classes (See Chapter 2)

Class

Rate

Examples

8

20%

Furniture, photocopiers

10

30%

Vans, trucks, tractors and computer equipment

13

Straight-line

22

50%

Leasehold improvements

Pollution control equipment

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 24

Depreciation on $10,000 Furniture (CCA Class 8, 20% rate)

Year

UCC t

CCA

UCC t+1

1

$5,000

$1,000

$4,000

2

9,000

1,800

7,200

3

7,200

1,440

5,760

4

5,760

1,152

4,608

5

4,608

922

3,686

6

3,686

737

2,949

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 25

CCA on Assets of $10,000 by year

Year

Class 8

Class 10

Class 22

1

$1,000

$1,500

$2,500

2

1,800

2,550

3,750

3

1,440

1,785

1,875

4

1,152

1,250

938

5

922

875

469

6

737

612

234

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 26

Example: Fairways Equipment and Operating Costs

Two golfing buddies are considering opening a new driving range, the

“Fairways Driving Range” (motto: “We always treat you fairly at Fairways”).

Because of the growing popularity of golf, they estimate the range will

generate rentals of 20,000 buckets of balls at $3 a bucket the first year, and

that rentals will grow by 750 buckets a year thereafter. The price will remain

$3 per bucket.

Capital spending requirements include:

Ball dispensing machine

Ball pick-up vehicle

Tractor and accessories

$ 2,000

8,000

8,000

$18,000

All the equipment is Class 10 CCA property, and is expected to have a

salvage value of 10% of cost after 6 years.

Anticipated operating expenses are as follows:

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 27

T10.10 Example: Fairways Equipment and Operating Costs (concluded)

Working Capital

Operating Costs (annual)

Land lease

$ 12,000

Water

1,500

Electricity

3,000

Labor

30,000

Seed & fertilizer

2,000

Gasoline

1,500

Maintenance

1,000

Insurance

1,000

Misc. Expenses

1,000

Initial requirement = $3,000

Working capital requirements

are expected to grow at 5%

per year for the life of the

project

$53,000

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 28

T10.11 Example: Fairways Revenues, Depreciation, and Other Costs

Projected Revenues

Year

Buckets

Revenues

1

20,000

$60,000

2

20,750

62,250

3

21,500

64,500

4

22,250

66,750

5

23,000

69,000

6

23,750

71,250

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 29

T10.11 Example: Fairways Revenues, Depreciation, and Other Costs (continued)

Cost of balls and buckets

Year

Cost

0

$3000

1

$3,150

2

3,308

3

3,473

4

3,647

5

3,829

6

4020

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 30

T10.11 Example: Fairways Revenues, Depreciation, and Other Costs (concluded)

Depreciation on $18,000 of Class 10 CCA equipment

Year

UCC t

CCA

UCC t+1

1

9,000

2,700

$15,300

2

15,300

4,590

10,710

3

10,710

3,213

7,497

4

7,497

2,249

5,248

5

5,248

1,574

3,674

6

3,674

1,102

2,572

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 31

T10.12 Example: Fairways Pro Forma Income Statement

Year

1

Revenues

$60,000

2

3

4

$62,250 $64,500 $66,750

5

6

$69,000 $71,250

Variable costs

Fixed costs

53,000

53,000

53,000

53,000

53,000

53,000

Depreciation

2,700

4,590

3,213

2,249

1,574

1,102

$4,300

$4,660

Taxes(20%)

860

932

1,657

2,300

Net income

$3,440

$3,782

$6,630

$9,201

EBIT

$8,287 $11,501

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

$14,426 $17,148

2,885

3,429

$11,541 $13,719

Slide 32

T10.13 Example: Fairways Projected Changes in NWC

Projected increases in net working capital

Year

Net working capital

Change in NWC

0

$ 3,000

$ 3,000

1

3,150

150

2

3,308

158

3

3,473

165

4

3,647

174

5

3,829

182

6

4,020

- 3,829

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 33

T10.14 Example: Fairways Cash Flows

Operating cash flows:

Year

0

EBIT

$

0

+ Depreciation

$

0

– Taxes

$

0

Operating

= cash flow

$

0

1

4,300

2,700

860

6,140

2

4,660

4,590

932

8,318

3

8,287

3,213

1,657

9,843

4

11,501

2,249

2,300

11,450

5

14,426

1,574

2,885

13,115

6

17,148

1,102

3,429

14,821

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 34

T10.14 Example: Fairways Cash Flows (concluded)

Total cash flow from assets:

Year

OCF

– Chg. in NWC – Cap. Sp. = Cash flow

0

$ 3,000

$18,000

– $21,000

1

6,140

150

0

5,990

2

8,318

158

0

8,160

3

9,843

165

0

9,678

4

11,450

174

0

11,276

5

13,115

182

0

12,933

6

14,821

-3829

-1,440*

20,090

0

$

* after tax

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 35

Fairways Cash Flow Example

Assume a discount rate of 20% - what is the NPV?

IRR??

Payback ?

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 36

Present Value of the Tax Shield on CCA

Shortcut in establishing future cash flows - using a formula that

replaces the detailed calculation of yearly CCA

The formula is based on the theory that the tax shield from

CCA continues in perpetuity as long as there are assets in that

particular CCA class.

C= total capital cost of the asset which is added to the pool

d= CCA rate for that asset class

Tc =company’s marginal tax rate

k = discount rate

S = salvage or disposal value of the asset

n = asset life in years

PV of tax shield on CCA = (CdTc)/d+k *(1+.5k)/1+k - Sdtc/d+k*1/(1+k)n

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 37

Alternative approaches in calculating OCF

Let:

OCF = operating cash flow

S

= sales

C

= operating costs

D

= depreciation

T

= corporate tax rate

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 38

Alternative Approaches in Calculating OCF (concluded)

The Tax-Shield Approach

OCF

(S - C - D) + D - (S - C - D) T

=

(S - C) (1 - T) + (D T)

=

(S - C) (1 - T) + Depreciation x T

……cash flow w/o dep’n plus dep’n tax shield

The Bottom-Up Approach

OCF

=

=

(S - C - D) + D - (S - C - D) T

=

(S - C - D) (1 - T) + D

=

Net income + Depreciation

…..start with accounting net income plus

dep’n

The Top-Down Approach

OCF

=

(S - C - D) + D - (S - C - D) T

=

(S - C) - (S - C - D) T

=

Sales - Costs – Taxes

…..start at top of income statement – leave

out non cash flows

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 39

Example: A Cost-Cutting Proposal

Consider a $10,000 machine that will reduce pretax operating costs

by $3,000 per year over a 5-year period. Assume no changes

in net working capital and a scrap (i.e., market) value of $1,000 after five years.

For simplicity, assume straight-line depreciation. The marginal tax

rate is 34% and the appropriate discount rate is 10%.

Using the tax-shield approach to find OCF:

OCF

=

(S - C)(1 - T) + (Dep T)

=

[$0 - (-3,000)](.66) + (2,000 .34)

=

$1,980 + $680 = $2,660

The after-tax salvage value is:

market value - (increased tax liability) = market value - (market value - book) T

= $1,000 - ($1,000 - 0)(.34) = $660

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 40

Example: A Cost-Cutting Proposal (concluded)

The cash flows are

Year

OCF

Capital spending

Total

0

-$10,000

-$10,000

1

2,660

0

2,660

2

2,660

0

2,660

3

2,660

0

2,660

4

2,660

0

2,660

5

2,660

+660

3,320

0

$

….key point here is the project economics are driven by a reduction in

operating costs – depicted as positive cash flow for the project

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 41

Evaluating Equipment with Different Lives

The goal is to still maximize net present value but when

system/equipment have different lives or time frames we need

to establish what the ‘equivalent annual cost’ (EAC) is

The equivalent annual cost is the present value of a project’s

costs calculated on an annual basis (think annuity!)

PV of costs = EAC * annuity factor

EAC = PV of costs/Annuity factor

Annuity factor = (1-present value factor)/r

(1-(1/1+r)t )r

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 42

Example: Setting the Bid Price

The Canadian Forces are seeking bids on Multiple Use Digitizing Devices (MUDDs). The contract

calls for4 units per year for 3 years. Labor and material costs are estimated at $10,000 per

MUDD.

Production space can be leased for $12,000 per year. The project will require $50,000 in new

equipment which is expected to have a salvage value of $10,000 after 3 years. Making MUDDs

will require a $10,000 increase in net working capital. Assume a 34% tax rate and a required

return of 15%. Use straight-line depreciation to zero.

Increases

in NWC

Capital

spending

Total

= cash flow

0

– $10,000

– $50,000

– $60,000

1

OCF

0

0

OCF

2

OCF

0

0

OCF

3

OCF

10,000

+ 6,600

OCF + 16,600

Year

0

Operating

cash flow

$

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 43

Example: Setting the Bid Price (continued)

Taking the present value of $16,600 in year 3 ( = $10,915 at

15%) and netting against the initial outlay of – $60,000 gives

Year

0

Total

cash flow

–

$49,085

1

OCF

2

OCF

3

OCF

The result is a three-year annuity with an unknown cash flow

equal to “OCF.”

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 44

T10.19 Example: Setting the Bid Price (continued)

The PV annuity factor for 3 years at 15% is 2.283. Setting NPV = $0,

NPV = $0 = – $49,085 + (OCF 2.283), thus

OCF = $49,085/2.283 = $21,500

Using the bottom-up approach to calculate OCF,

OCF = Net income + Depreciation

$21,500 = Net income + $50,000/3 = Net income + $16,667

Net income = $4,833

Next, since annual costs are $40,000 + $12,000 = $52,000

Net income = (S - C - D) (1 - T)

$4,833 = (S .66) - (52,000 .66) - (16,667 .66)

S = $50,153/.66 = $75,989.73

Hence, sales need to be at least $76,000 per year (or $19,000 per MUDD)!

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 45

Example: Setting the Bid Price -another example

Background: Suppose we also have the following information.

1.

The bid calls for 20 MUDDs per year for 3 years.

2.

Our costs are $35,000 per unit.

3.

Capital spending required is $250,000; and

depreciation = $250,000/5 = $50,000 per year

4.

We can sell the equipment in 3 years for half its original cost: $125,000.

5.

The after-tax salvage value equals the cash in from the sale of the

equipment, less the cash out due to the increase in our tax liability

associated with the sale of the equipment for more than its book value:

Book value at end of 3 years = $250,000 - 50,000(3) = $100,000

Book gain from sale = $125,000 - 100,000 = $25,000

Net cash flow = $125,000 - 25,000(.39) = $115,250

6.

The project requires investment in net working capital of $60,000.

7.

Required return = 16%; tax rate = 39%

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 46

Example: Setting the Bid Price (continued)

The cash flows ($000) are:

0

1

OCF

2

$OCF

$OCF

3

$OCF

Chg. in NWC

- $ 60

+ 60

Capital Spending

- 250

______

______

+115.25

- $310

$OCF

$OCF

$OCF +

175.25

Find the OCF such that the NPV is zero at 16%:

+$310,000 - 175,250/1.163

=

OCF (1 - 1/1.163)/.16

$197,724.74

=

OCF 2.2459

OCF

=

$88,038.50/year

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 47

Example: Setting the Bid Price (concluded)

If the required OCF is $88,038.50, what price must we bid?

Sales

$_________

Costs

700,000.00

Depreciation

EBIT

Tax

Net income

50,000.00

$_________

24,319.70

$ 38,038.50

Sales = $62,358.20 + 50,000 + 700,000 = $812,358.20 per year, and

the bid price should be $812,358.20/___ = ________ per unit.

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 48

Example: Setting the Bid Price (concluded)

If the required OCF is $88,038.50, what price must we bid?

Sales

$812,358.20

Costs

700,000.00

Depreciation

EBIT

Tax

Net income

50,000.00

$ 62,358.20

24,319.70

$ 38,038.50

Sales = $62,358.20 + 50,000 + 700,000 = $812,358.20 per year, and

the bid price should be $812,358.20/20 = $40,618 per unit.

copyright © 2002 McGraw-Hill Ryerson, Ltd

Slide 49