THE IMPACT OF DOMESTIC ANTI-NEOLIBERAL CONTENTION ON THE

THE IMPACT OF DOMESTIC ANTI-NEOLIBERAL CONTENTION ON THE

NEGOTIATION OUTCOME OF THE FREE TRADE AREA OF THE AMERICAS

(FTAA)

A Thesis

Presented to the faculty of the Department of Government

California State University, Sacramento

Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF ARTS in

International Affairs by

Michaela Bruckmayer

SPRING

2012

THE IMPACT OF DOMESTIC ANTI-NEOLIBERAL CONTENTION ON THE

NEGOTIATION OUTCOME OF THE FREE TRADE AREA OF THE AMERICAS

(FTAA)

A Thesis by

Michaela Bruckmayer

Approved by:

__________________________________, Committee Chair

David R. Andersen, PhD.

__________________________________, Second Reader

Nancy Lapp, PhD.

____________________________

Date ii

Student: Michaela Bruckmayer

I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis.

__________________________, Graduate Coordinator ___________________

David R. Andersen, PhD Date

Department of International Affairs iii

Abstract of

THE IMPACT OF DOMESTIC ANTI-NEOLIBERAL CONTENTION ON THE

NEGOTIATION OUTCOME OF THE FREE TRADE AREA OF THE AMERICAS

(FTAA) by

Michaela Bruckmayer

At the summit of American nations in 1994, thirty- four countries in the western hemisphere agreed to form the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA), an agreement that would include all democratic nations on the American continent. However, despite promising progress made during the first rounds of negotiations the deadline of January

1, 2005 was missed and no agreement has been reached. This study examines the possibility that negotiators were unable to reach an agreement because the application of free trade and other neoliberal policies in the western hemisphere, while encouraged by international institutions, created dissatisfaction among the general population, especially in Latin American countries. Eventually, this dissatisfaction manifested itself in the form of social movements protesting the implementation of further neoliberal reforms, in some cases eventually threatening the political stability of nations. This thesis asks the question whether the anti-neoliberal movements in Latin America influenced their respective government’s decision to support or abandon the FTAA.

In order to address this question, this study analyzes the cases of Argentina, Chile,

Nicaragua, and Bolivia. Each of these cases will undergo a three-step analysis. First, the iv

countries’ economic performance between 1994 and 2005 will be evaluated through the analysis of economic indicators, which are derived from datasets provided by the World

Bank and the United Nations, as well as news and secondary sources. Second, each case will be studied for episodes of contention and social movements protesting free trade and neoliberal reforms occurring during the FTAA negotiations. The data for this methodological step mostly stems from secondary sources and news articles reporting about the events. The third step of the analysis identifies each country’s position on the

FTAA by reviewing news accounts and press releases that quote country officials or trade representatives expressing their respective government’s intention and position in regards to the status of the FTAA negotiations. The data was obtained through the LexisNexis

News database, the Google News search engine and from secondary sources.

The results of the study indicate that countries experiencing strong social movements were less likely to support the FTAA than countries experiencing weak anti-neoliberal contention. These results point towards a relationship between national social movements and the outcome of international negotiations.

_________________________, Committee Chair

David R. Andersen, PhD.

_______________________

Date v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Dr. David Andersen for giving me the opportunity to conduct this thesis research. Completing this study has been a challenging, yet very rewarding experience and I am very grateful for Dr. Andersen’s guidance, feedback, and support. I would also like to thank Dr. Nancy Lapp for agreeing to serve as my second reader and for her valuable and much appreciated suggestions. Many thanks go out to my family for their unconditional support throughout my entire educational journey. vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ vi

List of Tables ..................................................................................................................... ix

List of Figures ..................................................................................................................... x

Chapter

1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1

Relevance of this Study .................................................................................................. 4

Historic Background ....................................................................................................... 7

2. LITERATURE REVIEW ............................................................................................. 11

Civil Society and International Negotiations ................................................................ 11

Free Trade: A World of Winners and Losers ............................................................... 14

Contentious Politics in Latin America .......................................................................... 21

3. THE ARGUMENT ....................................................................................................... 27

Argument and Hypotheses ............................................................................................ 27

Case Selection ............................................................................................................... 29

Method of Analysis and its Underlying Concepts ........................................................ 31

4. CASE STUDIES ........................................................................................................... 35

Introduction ................................................................................................................... 35

The Case of Argentina .................................................................................................. 36

Argentina’s Economic Performance ......................................................................... 36

Anti-Neoliberal Contention in Argentina ................................................................. 40

Argentina and the FTAA .......................................................................................... 47

The Case of Chile ......................................................................................................... 48

Chile’s Neoliberal Road ............................................................................................ 49

Chile’s Economic Performance ................................................................................ 53

Contentious Politics in Chile .................................................................................... 55

Chile and the FTAA .................................................................................................. 58

The Case of Nicaragua .................................................................................................. 59 vii

Nicaragua’s Path to Democracy ................................................................................ 60

Radical Neoliberalism in Nicaragua ......................................................................... 61

Contentious Politics in Nicaragua ............................................................................. 67

Nicaragua and the FTAA .......................................................................................... 74

The Case of Bolivia ...................................................................................................... 76

Bolivia’s Economy .................................................................................................... 77

Contentious Politics in Bolivia ................................................................................. 81

Bolivia and the FTAA ............................................................................................... 88

5. CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................. 90

Results ........................................................................................................................... 90

Implications for the Literature ...................................................................................... 92

Concluding Remarks ..................................................................................................... 94

Appendix ........................................................................................................................... 95

Bibliography ..................................................................................................................... 99 viii

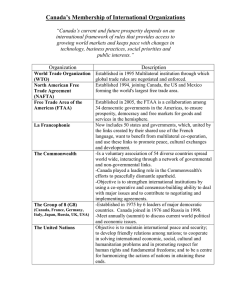

LIST OF TABLES

Tables Page

ix

LIST OF FIGURES

Figures Page

1. Theoretical Foundation ............................................................................................. 27

x

1

Chapter One

INTRODUCTION

At the summit of American nations in 1994, thirty- four countries in the western hemisphere agreed to undertake the ambitious project of forming a free trade agreement that would include all democratic nations on the American continent. The only American nation excluded from the negotiation was non-democratic Cuba (Rynerson 2007: 183).

The Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) negotiations were formally launched at the

Summit of the Americas meeting in 1998 at Santiago, Chile and were scheduled to be completed by 2005. However, despite promising progress made during the first rounds of negotiations the deadline of January 1, 2005 was missed and no agreement has been reached (Goldstein 2007: 88).

The objective of this study is to identify and evaluate a possible reason for the abandonment of what has been referred to as “the most ambitious free trade initiative in the postwar trading system” (Schott 2005: 1). Since the failure of the negotiations, many countries have negotiated bilateral trade agreements with other nations on the continent, indicating that American nations are still interested in negotiating free trade agreements.

Considering this, the fact that the continent wide free trade zone failed to be realized provides an interesting puzzle.

There are various factors that shape the outcome of international negotiations.

According to Robert D. Putnam, negotiations outcomes are a combination of international pressures and domestic preferences (Putnam 1988: 430). These domestic

2 preferences are influenced by countries’ governmental structure and the influence of civil society and interest groups (Putnam 1988: 434). When it comes to free trade negotiations an important aspect for the domestic constituents are the impacts of the agreements on the population. According to the theory of free trade, countries involved in the agreements should experience economic growth and modernization (Dornbusch 1992: 80; Irwin

2009: 29; Rodrik 1992: 89). At the same time, however, free trade can also increase income inequalities and can have negative impacts on the wealth of individuals. Free trade therefor leads to the creation of economic winners and losers. But since engaging in free trade is supposed to increase a country’s standard of living, the theory of free trade assumes that the gains obtained will “trickle-down” to society as a whole, eventually compensating the losers in the long-run (Farmer 2006: 67, Garrett 2004). However, whether this actually occurs is a major point of contestation, among academia and policy makers alike.

As pointed out by Sidney Tarrow, when people perceive a threat to their livelihood, as is often the case for the losers of free trade, they are likely to mobilize and use methods that will demand the attention of the government (Tarrow 2011: 44). If the

FTAA had been realized, it would have led to the creation of a single market covering approximately 850 million people (Rynerson 2007: 183). Because of the extent of the agreement and the large number of people that could have been subjected to potential negative impacts, people across the continent mobilized and participated in transnational anti-globalization movements, protesting the FTAA. Much of the literature regarding the

role of civil society in the FTAA negotiations has focused on this contentious politics

3 phenomenon.

However, in connection to the FTAA, the literature pays little attention to the domestic social movements that occurred simultaneously to the transnational movements.

Social movements protesting the impacts of neoliberal reforms in their respective countries have characterized the political landscape in Latin America ever since nations first transitioned to free market societies, in some cases eventually bearing a threat to the political stability of the nations (Stahler-Sholk et al. 2007: 5). Since leaders of democratic countries are dependent on their public’s favor, this particular study asks the question whether the domestic anti-neoliberal movements in Latin America influenced their respective government’s decision to support or abandon the FTAA.

Given that the governments participating in the FTAA negotiations believed that free trade would raise society’s standard of living and that the losers would eventually be compensated, this study argues that the government’s decision to support or oppose the formation of the FTAA depended on the strength of the domestic social movements protesting the agreement. Further, this study assumes that nations that were still recording weak economic performance after the initiation of the FTAA negotiations despite their transition towards a neoliberal market economy years earlier are even less likely to support the formation of the FTAA. Accordingly, this study is going to analyze the strength of the economic performance and the strength of contentious politics occurring in four Latin American countries during the time of the FTAA negotiations. The results

4 of this study indicate that countries experiencing strong social movements opposing free trade and the further implementation of neoliberal policies were less likely to support the continuation of the FTAA negotiations.

In order to evaluate the above outlined assessment, this thesis consists of the following chapters. The remainder of the introductory chapter points out the relevance and scope of this study followed by a brief history of continent wide trade relations and the FTAA negotiations. Chapter two provides an overview of the relevant literatures including the role of civil society in international negotiations, the aspects of free trade that gave rise to the movements, and the principles of social movement theory and contentious politics. Chapter three outlines this study’s argument and hypotheses and introduces the methods used in the attempt to answer this study’s research question. The case studies in chapter four provide an analysis of the strength of the economic performance and anti-neoliberal contentious politics in Argentina, Chile, Nicaragua, and

Bolivia during the time period of the FTAA negotiations from 1994 until 2005. In addition, the hypotheses proposed in chapter three are going to be tested by assessing the aforementioned governments’ position on the FTAA. The final chapter summarizes the results of this study and the conclusions reached.

Relevance of this Study

As pointed out by Victor M. Sergeev, “the study of negotiation processes is one of the most complicated fields of political science” (Sergeev 2002: 65) and “one of the most complex human activities” (Sergeev 2002: 64). However, in our increasingly

5 interdependent world nations are often communicating through the means of a negotiation. In many cases the outcome of an international negotiation can have significant impacts on the future of millions of people. As Starkey et al. point out,

“sometimes a negotiation is all that stands between war and peace” (Starkey et al. 2005:

1; Raiffa 2002: 9). Considering the extent of the impacts negotiation outcomes can have, we must continue to explore the dimensions of international negotiations despite some conceptual and methodological difficulties.

In addition, as pointed out by Victor A. Kremenyuk, negotiations have become more complex due to the increasing interdependence between nations’ economies and issue areas. This has encouraged an increase in the number of actors involved in negotiations and to the development of what Kremenyuk refers to as “public diplomacy”

(Kremenyuk 2002: 24). This includes the involvement of: “international organizations, business and industrial units, political parties and movements, and social and religious communities” (Kremenyuk 2002: 24) that now have a stake in international negotiations and are especially impacted by economic agreements and therefore are starting to play a more active role in the negotiations (Kremenyuk 2002: 24). Given the high number of people that would be affected by a continent wide free trade agreement, the case of the

FTAA negotiations provides a great opportunity to study how civil society can influence the outcome of multilateral negotiations. During the FTAA negotiations, many civil society groups opposing the agreement took the initiative to try to influence their governments’ decision to support the formation of the FTAA. This study argues that the

6 reason for the public’s opposition to the FTAA lies within the functionality and the paradox of the neoliberal paradigm, which provides the foundation for free trade. As will be explained in further detail in the following chapters, neoliberal economics and free trade policies promise to raise a country’s standard of living and lead to economic development and modernization (Dornbusch 1992: 80; Rodrik 1992: 89; Irwin 2009: 29).

But in order to implement neoliberal policies, Latin American nations had to undertake the reconstruction of their government and economy, which can negatively impact the livelihood of thousands of people (Dornbusch 1992: 74; Garrett 2004: 84).

Neoliberalism, however, provides for the creation of winners and losers while assuming that the gains earned by engaging in free trade will eventually “trickle-down” to the rest of society and compensate the losers in the long-run (Farmer 2006: 67, Garrett 2004).

Nevertheless, this study challenges the assumption of the neoliberal paradigm by analyzing nations’ economic performance and argues that the losers of free trade mobilized in an attempt to stop the institutionalization of neoliberalism in the region that would have resulted from the creation of the FTAA (Roberts 2008; Carranza 2004: 324).

This study is going to evaluate whether, depending on the strength of the movement, the civil society organizations were able to influence their respective government’s decision to support or abandon the formation of the FTAA. Therefore, the results of this thesis may contribute to the study of the relationship between domestic actors and the international negotiation setting. In addition, analyzing the relationship between countries’ economic performance and the strength of anti-neoliberal contentious politics

can contribute to the debate surrounding free trade, and the emergence, facilitation and

7 effects of social movements and contentious politics.

Historic Background

The vision of a continent wide free trading system is nothing new. While the idea of a continent wide free trade zone did not take form until the launch of the FTAA negotiations in 1994, it has been in the mind of policy makers for almost two hundred years. In 1889, at the First International Conference of the American States, U.S.

Secretary of State James G. Blaine suggested the establishment of a customs union between nations in the western hemisphere (Maryse 2007: 2). However, at that time, the idea of opening economies did not find its way into countries’ trade policies. The United

States for example, instead entered into a period of a protectionist foreign policy. This included the passing of protectionist legislation such as the McKinney Tariff Act of 1890 and the Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930, which substantially increased duties on imports

(Maryse 2007: 4). However, as a reaction to the great depression, the United States started to look for ways of increasing exports abroad, as well as strengthening relations with key allies (Maryse 2007: 4). Accordingly, the U.S. Congress passed the Reciprocal

Trade Agreement Act in 1934, increasing the executive office’s trade negotiation power in the hope to ease the facilitation of trade agreements (Ehrlich 2008: 428). By the end of

World War II, the United States was steadily shifting towards becoming the world’s most powerful nation, and following the example set by the precedent hegemonic power, Great

8

Britain, the United States started to move toward a more liberal foreign trade policy

(Feinberg 2003: 1020).

While approaches varied from nation to nation, Latin American countries applied protectionist policies as their primary trading model since the 1930s (Dornbusch 1992:

70). This faith in this economic policy was enhanced by the ideas of the Argentine economist Raúl Prebisch, who advocated for an import substitution model through the doctrine from the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLAC)

(Dornbusch 1992: 71). The model was based on the idea that domestic industries should be developed by protecting them from international competition through high tariffs or quotas (Dornbusch 1992: 72). The model strongly contrasted with the general economic liberalization trend set forth by the international community and by industrialized nations.

However, during the 1950s and 1960s the predecessor of the World Trade Organization

(WTO), the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), and the newly developed

UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) still provided room for developing countries to maintain their protectionist policies (Dornbusch 1992: 72).

By the 1980s, the import-substitution model resulted in radical macro-economic instability and in the sovereign debt crisis (Grilli 2005: 18). Latin American nations were faced with pressure from the world’s leading economies and international institutions to place greater emphasis on economic openness, reduced government intervention in the economy, market incentives, and enhanced competition (Grilli 2005: 18). Eventually, nations in Latin America started to pursue liberal economic policies in order to receive

9 debt assistance from international financial institutions (Grilli 2005: 18). Accordingly, by the beginning of the 1990s, most Latin American nations had transitioned to a neoliberal market economy.

Eventually, the paradigm’s status and its advocacy by the international community caused the spread of free trade agreements across the globe, including the western hemisphere. With the implementation of North American Free Trade Agreement

(NAFTA) in 1994, Mexico gained unrestricted access to the largest market in the world

(Feinberg 2003: 1021). Wanting a piece of the pie, nations in the hemisphere approached the idea of forming a hemisphere wide trade agreement at the Summit of the Americas in

1994 (Feinberg 2003: 1021).

Accordingly, in December 1994, at the Summit of the Americas, the United States agreed with thirty three Latin American nations to form a Free Trade Area of the

Americas (FTAA) by 2005 (Feinberg 2003: 1021). The decision to initiate FTAA negotiations corresponded with the demands of the international system and seemed a profitable option to Latin American nations (Feinberg 2003: 1025). The FTAA was supposed to eliminate any barriers to trade and investment between the thirty-four democratic nations. In addition, according to Paul Rynerson, the objectives of the FTAA included: strengthening democracy in the region, promoting prosperity through free trade, eliminating poverty and discrimination, and promoting environmental standards

(Rynerson 2007: 184). The nations agreed to achieve substantial progress towards building the FTAA by 2000 and to complete negotiations by the year of 2005 (Martinez

et al. 2003: 4). When the negotiations were first launched in 1994, enthusiasm for the

10 project was widespread (Hornbeck 2001: 183). The nations’ confidence in the theory of free trade was so strong that at first the thirty-four countries committed to draft an agreement that was to be adapted by all countries, on all terms (Hornbeck 2001: 183).

Over the next few years, negotiations were conducted through eight ministerial meetings and four American Summit meetings at different locations throughout the western hemisphere (Hornbeck 2005: 2). But by the FTAA meeting in November of 2003 in

Miami, negotiators abandoned the idea that all countries had to accept and implement all negotiated conditions of the agreement at once (Goldfarb 2004: 3). Instead, the negotiators agreed on a two-tier version of the agreement, which became known as the

FTAA-lite. Based on the FTAA-lite, countries were to agree to a minimum set of conditions and could implement further aspects of the FTAA at their own discretion

(Goldfarb 2004: 3; Hornbeck 2005: 5). But the negotiators never finalized the minimum set of conditions or made plans at what rates the countries would adapt and implement the remaining terms of the agreement. Eventually, the deadline of January 1, 2005 was missed and no agreement had been reached. It is the objective of this thesis to evaluate whether the contentious politics in Latin America opposing the formation of the FTAA were able to influence their respective government’s position on the FTAA and therefore indirectly prevented the realization of the FTAA agreement.

11

Chapter Two

LITERATURE REVIEW

Civil Society and International Negotiations

International negotiations and diplomacy are always characterized by an intermingling of domestic and international affairs. A prominent approach for accounting for this relationship between nation’s domestic conditions and international policy outcomes has been created by game-theorists (Starkey et al. 2005: 5). A significant contribution has been made by Robert D. Putnam when he published his article

“Diplomacy and Domestic Politics: the Logic of Two-level Games” in 1988. In this article, Putnam introduces a framework that can explain the mechanisms of the interaction between diplomacy and domestic politics (Putnam 1988: 430). By analyzing different international negotiations, including the Bonn summit conference of 1978,

Putnam illustrates that the outcomes of negotiations are a combination of international pressures and domestic preferences (Putnam 1988: 430). According to Putnam, negotiators are responsible for achieving what is in the best interest of their respective nations. These interests are shaped by domestic factors, such as the structure of the state, and the influence of civil society and interest groups. In addition, the national ratification process of international agreements influences the negotiator’s bargaining power (Putnam

1988: 434). Based on Putnam’s theory, international agreements are reached through the intermingling of negotiators’ preferences and the pressures on the international level as to

what can get ratified at home, as well as in the other country. Putnam illustrates this

12 intermingling as a two-level game (Putnam 1988: 434).

Putnam’s two-level game theory provides a framework for how civil society can influence international negotiations by putting pressure on their respective governments.

Negotiations at the international level are usually prone to high visibility by the respected domestic and international realm, which encourages the participation of non-state actors

(Starkey et al. 2005: 3). This aspect should be viewed in a positive light because participation of all impacted groups increases the chance of reaching a democratic agreement. Therefore, as pointed out by Paul Rynerson, the FTAA negotiations encouraged feedback in all possible forms, including from labor unions, the private sector, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) (Rynerson 2007: 185). Negotiators hoped that universal participation would help ensure the public’s acceptance of the FTAA

(Rynerson 2007: 185). However, others have exposed the negotiators’ attempts to hear the public’s side as a mere façade that was supposed to prevent further public criticism of free trade. As stated by Stahler-Sholk et al, the FTAA’s “civil society participation committee” (ftaa-alca.org) can be compared to “Powerpoint-ready workshops” created by financial institutions and “so-called development agencies” to instruct the leaders of civil-society groups in the benefits of free trade agreements (Stahler-Sholk et. al 2007:

12). This marginalization of the public in the negotiation of an agreement that may negatively impact the lives of thousands of people could have encouraged the emergence of contentious politics opposing the formation of a continent wide free trade zone.

13

In addition, the structure of the FTAA negotiations encouraged further marginalization of the population. Traditionally, international negotiations are conducted by sovereign states, often through their political leaders or a designated diplomat (Starkey et al. 2005). However, international negotiations have shifted away from the “traditional” actors to include a wider variety of negotiators. In recent years, it has become more and more common for governments to delegate negotiation authority to known experts on the respective negotiation issue, such as economists or trade specialists instead of government officials (Starkey et al. 2005: 60). This can have important implications for the contents and outcome of negotiations. Government officials and head of states are more dependent on reelection, and therefore are more inclined to listen to the needs of the public. Issue experts, however, are more likely to overlook the human implications an economic decision can have (Starkey et al. 2005: 60). The content of the FTAA negotiations was conducted through nine different working groups (Hornbeck 2005: 2;

Rynerson 2007). Therefore, the likelihood that the continent wide free trade agreement could threaten the livelihood of individuals was further increased by the structure of the

FTAA negotiations, facilitating the rise of social movements.

Since leaders of democratic nations are dependent on their public’s favor, this study argues that social movements can indirectly influence the outcome of an international negotiation, even if not present at the negotiation table itself. As outlined by

Putnam, negotiation outcomes and foreign policies are a combination of international pressures as well as domestic conditions, including the pressures exercised by civil

14 society groups. In order to assess what factors influence the character of a social movement, this thesis is going to rely on the concepts established in the social movement and contentious politics literature. Before outlining these principles, the following section is going to provide an overview of the debate surrounding free trade and the issues that caused the social movements to emerge as an actor in the international negotiations. As chapter three is going to illustrate in further detail, all three literatures are relevant in terms of understanding the relationship between anti-neoliberal contentious politics and the outcome of the FTAA negotiations.

Free Trade: A World of Winners and Losers

As previously outlined in chapter one, after the failure of the import substitution model, Latin America adopted neoliberalism as its primary economic model, which according to the view of international institutions and the industrialized world was the favored way to achieve economic growth and sustainable development (Rodrik 1992:

89). In addition, according to Rudiger Dornbusch, trade liberalization facilitates the transfer of resources and know-how, and diversifies goods available to consumers, consequently empowering the workforce and increasing productivity (Dornbusch 1992:

74). This eventually leads to economic growth and modernization, which are important objectives for developing countries (Dornbusch 1992: 80). Accordingly, the theory of free trade promises economic gains to every country involved in trade and an increase in the population’s standard of living (Irwin 2009: 29).

15

These assumptions were apparently confirmed by the success of the East Asian

Newly Developed Countries, who are often identified as the role models of neoliberal development strategies. As pointed out by Anne Krueger in her book, Trade Policies and

Developing Nations, the so-called “Asian Tigers” were able to advance their economies by developing their export sector, focusing on an “outer-oriented trade strategy” (Krueger

1995: 16). An important aspect of this strategy was the deregulation of the labor market, for example through the elimination of minimum wages, which eventually led to an increase in industrial employment (Krueger 1995: 20). Krueger emphasizes that the

“outer-oriented” neoliberal trade strategy employed in East Asia is a more viable development strategy than the import substitution model often employed in Latin

America during the 1980s (Krueger 1995: 36). Inspired by the successes of the East

Asian economies, Latin American countries followed the lead of the Asian tigers and adopted the neoliberal paradigm as their primarily economic model. While her analysis is thorough, Krueger’s biggest shortcoming is that she does not sufficiently prove that the

East Asian nations’ strategy was indeed neoliberal. As pointed out by Ha-Joon Chang in his book Bad Samaritans. The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism , the opening of the Asian economies required a strong role of the state. According to

Chang, the East Asian countries were only able to reach the next level of development due to targeted government intervention and regulation (Chang 2008). This strongly contradicts the neoliberal paradigm, as well as the standards of the global multilateral trading system, which both call for the state’s role to be very limited and insists on

minimal government spending, regulation, taxation, and minimal interference in the

16 economy (Goldstein 2007: 30).

Krueger and Chang provide only two, although very influential, examples of how heavily contested neoliberalism as a development strategy is among academia and policy makers alike. A major point of contestation is that the neoliberal paradigm in itself provides for the creation of economic winners and loser. As the example of the deregulation of the labor market and the consequent elimination of minimum wage in the

East Asian countries showed, radical deregulation and minimal government interference are the foundation of neoliberalism (Goldstein 2007: 29). As explained by Dornbusch, in order to facilitate the transition to a free market society, nations need to adjust their economy and their production system so that they are able to compete in the international trading regime (Dornbusch 1992: 74). These domestic policy changes can have various impacts on the population. For example, as explained by Geoffrey Garret, one of these impacts can be an increase in income inequality and a consequent reduction of the middle class (Garrett 2004: 84). In his article, “Globalization’s Missing Middle” Garrett emphasizes that while globalization benefits many, it has special implications for middle income countries. According to Garrett, middle income countries have seen the least amount of gains from the neoliberal economic order, and often experienced the highest amounts of losses (Garrett 2004: 86). The author explains this phenomenon by stating that in order to compete in a liberalized international trading system, nations have to be able to offer something of value to other nations, or as Garret expresses it, find a niche

17 within that system (Garrett 2004: 85). However, middle income countries are faced with the challenge that they can neither provide the high skilled know-how traded by industrialized nations, nor the low-skilled labor offered by poor nations (Garrett 2004:

88). Because middle income countries do not have the necessary capabilities and resources to compete with the industrialized nations, they are left with the only option of

“dumbing-down” their economies and compete with the low income nations (Garrett

2004). Accordingly, the free market concept, while promising to raise the standard of living for society as a whole, creates income inequalities and has negative effects on the wealth of individuals (Farmer 2006: 67).

Since most of Latin America can be classified as middle-income countries,

Garrett’s argument bears important implications for the countries that participated in the

FTAA negotiations. However, the theory of free trade does not account for the possibility that parties involved in free trade agreements have various degrees of capabilities.

Instead, the neoliberal paradigm assumes that all individuals exist under the same economic conditions and capabilities, have equal resources and have “perfect” information available to make rational decisions (Goldstein 2007: 30). Since this does not correspond with the real world, critics have voiced the concern that the concept of free trade is a rather oversimplified model that shows no connection to the well-being of a population (Goldstein 2007: 30). Yet, international institutions and the industrialized world insisted that adopting the neoliberalism as their primary economic model is the best option for Latin American nations.

18

A possible explanation for this paradox could be the fact that even though the neoliberal paradigm does not account for various degrees of capabilities and development of members of a free trade agreement, the theory does provide for the creation of economic winners and losers. Neoliberals accept the fact that the talented can rise to the top, and that therefore as a consequence, always has to be a “bottom class” (Farmer 2006:

67). The greatest misconception about this argument is that this bottom class does not consist of common outsiders of society, such as criminals, who according to Adam

Smith, the founding father of free trade theory, deserve to be where they are at. Rather, this “bottom class” consists of people who lack the necessary resources to compete within the free trade system, either because of location, lack of education, lack of capital, or lack of technology (Farmer 2006: 67). However, supporters of neoliberalism further assume that the benefits obtained through free trade should eventually “trickle-down” to everybody in the nation and compensate losers in the long-run.

Testing this argument, David E. Hojman assesses Chile’s situation after its transition to neoliberal market policies and democracy. Hojman’s article, “Poverty and

Inequality in Chile: Are Democratic Politics and Neoliberal Economics Good for You?” investigates how the shift to democracy and the adoption of neoliberal policies in Chile have impacted the nation’s distribution of income and the alleviation of poverty (Hojman

1996: 73). Often credited as the economic role model of South America, recording some of the best social and economic indicators of the region, Hojman states that Chile is still characterized by a large income inequality, and not showing any significant

19 improvements since the transition to neoliberalism (Hojman 1996: 76). Hojman believes that causes can be found in two reasons (Hojman 1996: 73). According to Hojman, after the transition to neoliberalism the Chilean economy has become less labor intensive, requiring a higher-skilled labor force that the low education system in Chile was unable to provide. The second cause of the persistent income inequality can be found in the appreciation of the Chilean currency (Hojman 1996: 80). By reviewing the exchange rates with Chile’s main trading partners between 1987 and 1994, Hojman finds that the appreciation of the Chilean peso could have either led to an increase of poverty by damaging exports and jobs, but at the same time it helped alleviating poverty by reducing domestic prices (Hojman 1996: 81). Hojman concludes that while poverty fell after the transition to democracy and neoliberal market policies, income inequality visibly increased, reducing the size of the middle class. Hojman attributes this to the fact that while Chile’s social spending packages comprised about two-thirds of total expenditures; his regression analysis shows that the bottom quintile of the population only received about ten percent of the expenses. Hojman therefore argues that through well-targeted social spending, Chile could eventually improve poverty rates and decrease the large income inequality (Hojman 1996: 88). Although Hojman does not explicitly state it, his argument could be interpreted in a way that suggests that government intervention is needed in order for the gains promised by free trade to “trickle-down” to the ones at the bottom of society. However, since the theory itself preaches that the role of the government needs to be reduced to only facilitating smooth economic operations and that

the market will provide the “trickle-down” effect, one could argue that neoliberalism

20 does not bring the promised gains and that a continental free trade zone could increase income inequality and have a negative effect on the development of the region, especially in the case of nations which level of development does not equip them to effectively respond to the changes free trade may bring. This was made evident by Hojman’s analysis of Chile’s change in the demand in labor and the relationship to the educational system that was not sufficiently developed to respond.

When countries first agreed to initiate the FTAA negotiations in 1994, their faith in the neoliberal paradigm was strong and enthusiasm for the FTAA was widespread.

However, as the case studies in this thesis will show, after years of following the neoliberal paradigm, the gains did not always “trickle-down” to the losers of free trade.

While the segment of society that has the necessary resources and capabilities to compete in a free trade system may still support the idea of the FTAA, society in Latin America mobilized and demanded that public officials pay attention to their concerns (Carranza

2004; Roberts 2008). It is the objective of this study to evaluate whether these domestic social movements had an impact on governments’ decisions to support or oppose the formation of the agreement. In order to successfully evaluate the impact of the social movements on the outcome of the FTAA negotiations, one must consider the literature of social movements and contentious politics. Therefore, the following section is going to outline basic concepts of social movement theory and what factors contribute to the emergence, facilitation, and impacts of social mobilization in Latin America.

Contentious Politics in Latin America

In the book, Power in Movement: Social Movement and Contentious Politics,

Sidney Tarrow defines contentious politics as “collective actors united to fight elites, authorities and opponents” (Tarrow 2011: 4). According to Tarrow, collective action

21 becomes contentious when actors seek to influence institutions and introduce new policy ideas or claims through methods that challenge authority (Tarrow 2011: 7). Once these challenges of authority become more frequent and start to incorporate a sense of solidarity and common purpose among its members, it becomes a social movement

(Tarrow 2011: 9).

The method used for challenging authority is referred to as a “repertoire of contention,” which Tarrow defines as “the ways people act together in pursuit of shared interest” (Tarrow 2011: 39). Tarrow observes that a population tends to stick to a specific method of contention, be it sit-ins or road barricades, throughout generations. For example, people in Argentina have been relying on roadblocks for their repertoire of contention for several decades (Silva 2009: 74). A repertoire of contention that has been used before throughout a country’s history is well known to everyone and therefore, the opposed group will immediately recognize the movement’s action as a protest (Tarrow

2011: 39). However, a repertoire may change when a country experiences changes in its governmental or economic structure (Tarrow 2011: 39).

There are three popular modern repertoires used in contentious politics: disruption, violence, and a combination of these two (Tarrow 2011: 99). According to

22

Tarrow, “disruption is one of the strongest weapons of social movements” (Tarrow 2011:

103). But in order for disruption to sustain, it needs deeply dedicated participants that are willing to commit for a long period of time, which often proves to be difficult (Tarrow

2011: 104). In addition, the nature of disruptive action usually compels the reaction of the authorities, challenging the necessary long-term commitment of participants and eventually causing the movement to fail without it having achieved the desired results

(Tarrow 2011: 104). Authorities can react to the emergence of contentious politics by repression, facilitation, or a combination of these two. In general, the opponents’ reaction often depends on what type of contentious politics is allowed or considered illegal by the respective government (Tarrow 2011: 110).

On the other hand, if a disruptive movement manages to survive for too long, it runs into the risk of becoming institutionalized. A movement becomes institutionalized when the disruptive activity continues for so long that authorities and opponents eventually learn to work around the disruption, diminishing the movement’s effectiveness

(Tarrow 2011: 104). Contentious politics can also be violent. While this is a very risky and damaging form of contention, its advantage is that it usually receives the most international attention, which might increase its effectiveness (Tarrow 2011: 105).

There are a variety of factors that can contribute to the emergence of a social movement. According to Tarrow, contentious politics can be triggered when there are changes in the governmental structure or the national system that alters the opportunities for the public to interact with authority and events occur that compel actors to make

23 demands for people or groups of people that do not have proper resources to participate in the political realm (Tarrow 2011: 6). Accordingly, a country’s political opportunity structure, which “refers to features of regimes or institutions that facilitate or inhibit a political actor’s collective action and to changes in those features” (Tarrow, Tilly 2007:

49) can have important implication for the character of a social movement. Especially governmental capacity and the degree of democracy can have a significant impact on contentious politics (Tarrow, Tilly 2007: 55). Tarrow and Tilly define governmental capacity as “the extent to which governmental action affects the character and distribution of population, activity and resources within the governments’ territory”

(Tarrow, Tilly 2007: 55). Whether a country is democratic or not influences institutions which may again direct which movements may emerge by encouraging the existence of some groups while prohibiting the formation of others (Tarrow, Tilly 2007: 60). Tarrow points out, that democratic regimes have a greater tendency to recognize civil society’s right to express their contention and usually provide some means or channels for contentious politics to exist. Undemocratic or authoritarian regimes, however, might prohibit any type of public expression and may respond with persecution and violent repression of any mobilization, making even wide-spread contention difficult to sustain

(Tarrow, Tilly 2007: 113). Given the relevance the literature attributes to the relationship between a country’s regime and the character of contentious politics in said country, this study is going to take the political opportunity structure of the cases analyzed into consideration.

24

In addition, contentious politics commonly emerge when people feel deprived of their most basic rights, such as access to food, land, or water (Tarrow 2011: 44). The availability of these factors usually strongly depends on a country’s economic performance. The success and failures of a country’s economic policy have therefore important implications for contentious politics. In addition, civil society has a tendency to emerge as a political actor if people are unable to sustain a living and see a decrease in their access to food, housing, and sanitation, but the government fails to take action or is perceived to not adequately respond to a crisis (Starkey et al. 2005: 68).

However, the public does not necessarily mobilize solely because it is discontented with public policy. An important factor for mobilization is the public’s perception of policies being unfair (Tarrow 2011: 25). According to Tarrow, the idea of someone unfairly claiming land that actually belongs to someone else, or keeping a pantry full of bread while everybody else is starving usually greatly contributes to the mobilization and the severance of the episodes of contention. This idea of a “moral economy” was developed by E.P. Thompson (1971) and adds an interesting aspect to anti-neoliberal contention, especially in the case of Latin America, where free trade is known to create winners and losers, exacerbating the region’s already large income inequality.

But in the case of anti-neoliberal contention in Latin America, Kenneth M.

Roberts asserts that the reduction of the state and the accompanying elimination of channels of political participation for the economic less powerful, as well as the structural

25 manifestation of opportunities for the market-participants was one of the root causes for the anti-neoliberal uprisings in the region (Roberts 2008: 330). In a neoliberal market society, political participation is not defined in terms of citizenship, but rather in terms of market participation (Stahler-Sholk et al. 2007: 8). This ultimately leads to the economic and political marginalization of the losers of free trade. Ensuring rights and equal participation for all, and not just the economic powerful, is a large aspect of the social movements protesting neoliberal reforms. Eduardo Silva summarizes the motives for anti-neoliberal mobilization in Latin America as:

“socioeconomic grievances against free-market economic reforms; ethnic and cultural rights crystallizing into demands for plurinational societies and some degree of ethnic autonomy; and political claims for greater participation in democratic decision making and less corruption in politics.” (Silva 2009: 16).

However, social contention and mass mobilization has always been a part of political life in Latin America. What differs about Latin America’s anti-neoliberal mobilization as opposed to previous uprisings in the region is that movements protesting neoliberal policies are not necessarily interested in seizing power (Stahler-Sholk et al.

2007: 5). Instead, the most desirable outcomes for these “new” social movements are direct impacts on public policies (Tarrow, Tilly 2007: 86).

Another noteworthy characteristic of the new social movements during the FTAA regards the movements’ participants and actors of contentious politics. Whereas most recorded uprisings are driven by members of lower social standing, protesters during the

FTAA negotiations belonged to a variety of different social groups (Stahler-Sholk et al.

2007: 6). Participants in Latin American movements included the poorest segments of

26 society, the unemployed, self-employed and the traditional movement organizer such as labor unionists. In addition, people from the middle-class, teachers, professors, accountants, etc. joined forces with the laborers and the poor to voice their opposition to neoliberalism and free trade (Silva 2009: 77; Stahler- Sholk et al. 2007: 6).

In regards to the demands of the movement, Silva believes that the social movements did not contest capitalism itself, but specifically the neoliberal version of capitalism (Silva 2009: 3). Kenneth M. Roberts, however, points out that the source of the anti-neoliberal mobilization does not necessarily confirm the failure of the neoliberal paradigm. Rather, Roberts proposes that the imposed neoliberal market reforms failed to provide necessary social services and programs (Roberts 2008: 330). But had the neoliberal model actually led to the desired economic results, civil society would not have felt the need to mobilize and demonstrate their dissatisfaction with their current living situation. As the evidence presented in thesis is going to demonstrate, the introduction of the neoliberal market economy and the consequent reconstruction efforts had severe impacts on several sectors of the populations. However, as the cases presented in this study are going to show, the promised economic gains were relative and did not necessarily trickle-down. Accordingly, civil society started to demand the attention of their leaders and consequently started to become a relevant actor in the political realm.

While not directly present at the negotiation table, this study is going to assess whether domestic social movements were able to influence the outcome of an international free trade negotiation.

27

Chapter Three

THE ARGUMENT

Argument and Hypotheses

At the First Summit of the Americas in Miami, Florida in 1994, thirty-four

“Heads of State and Government” in the western hemisphere signed the Declaration of

Principles. In this declaration, the nations announced that,

“Free trade and increased economic integration are key factors for raising standards of living, improving the working conditions of people in the Americas and better protecting the environment. We, therefore, resolve to begin immediately to construct the "Free

Trade Area of the Americas" (FTAA), […].” (Summit-americas.org/miamiplan 1994).

As this quote shows, countries that liberalize their economies should experience economic growth and modernization, as promised by the theory of free trade. The theory further holds that while free trade only initially benefits the top segment of society, the gains obtained would eventually trickle-down to

Free Trade society as a whole. While free trade leads to the creation of economic winners and losers, the market would compensate the losers in the long-run. In the

Social

Movements case that this does not hold true, the social movements and contentious politics literature argues that people

International

Negotiations who feel deprived of their most basic rights and are unable to sustain a living are likely to mobilize against

Figure 1 Theoretical Foundation authorities. Since the public’s wellbeing is interlinked with a country’s economic conditions, this study assumes that the likelihood of the

28 public’s mobilization against the FTAA connects to a country’s economic performance.

Accordingly, in order to test whether the gains actually trickled-down to the losers of free trade, this thesis is first going to evaluate the economic performance of Latin American nations.

However, while contentious politics may be more likely to arise in nations with weak economic performance, this study assumes that the failure of the neoliberal paradigm alone was not sufficient to cause the head of states to abandon the FTAA negotiations. After all, the theory of free trade does not only provide for the creation of economic losers, but also of economic winners. What is questioned here is the assumption that the gains will eventually trickle-down, not that neoliberalism does not lead to any gains at all. Accordingly, since the sector of society that is able to compete within the free market system had an incentive to continue the negotiations, this argues that the government’s position on the FTAA related to the strength of domestic social movements and contentious politics. Therefore, after reviewing the economic performance of Latin American nations, the countries will be reviewed for the occurrence and characteristics of episodes of contention. After that, this study is going to assess country’s position on the FTAA.

Based on the above outlined assumptions, the following four hypotheses were drafted:

1.

Countries recording strong economic performance and weak social movements are most likely to support the FTAA.

2.

Countries recording strong economic performance and strong social movements are less likely to support the FTAA.

29

3.

Countries recording weak economic performance and strong social movements are least likely to support the FTAA.

4.

Countries recording weak economic performance and weak social movements are more likely to support the FTAA.

Case Selection

In order to test the above outlined hypotheses, the case study approach was chosen as method of analysis. Given that thirty-four countries participated in the FTAA negotiations, there are technically thirty-four possible case studies. But considering that this study’s general argument addresses contentious politics protesting neoliberal policies in Latin America, the United States, Canada and the small Caribbean nations can be excluded as possible case studies. The remaining options range from Brazil, one of the largest countries in the world, to the much smaller economies in Central America. Due to time and space constraints, it is not possible to analyze all Latin American nations in this study. To ease the application of this study’s methods and results to other cases, four medium size Latin American economies were selected to represent the Latin American nations engaged in the FTAA negotiations. In order to cover all possible scenarios, this study is going to select one country for each of the four categories described in figure 2.

30

Economic

Performance strong economic performance weak social movements weak economic performance weak social movements strong economic performance strong social movements weak economic performance strong social movements

Social Movements

Figure 2 : Possible Scenarios

Based on the above mentioned criteria, the cases selected include Argentina,

Chile, Nicaragua and Bolivia. All four Latin American nations participated in the FTAA negotiations between 1994 and 2005. Therefore, this is the set time frame used for analysis. The cases are assigned as followed. Chile was selected as a case study for a nation experiencing strong economic performance but weak social movements during the time of the FTAA negotiations. Argentina represents countries with strong economic performance and strong movements protesting the implementation of neoliberal reforms.

The cases of Bolivia and Nicaragua both represent nations with weak economic performance. However, while Bolivia experienced very strong contentious politics,

Nicaragua’s political landscape experienced comparatively weak episodes of antineoliberal contention. The data and analysis in chapter four is going to demonstrate how each of the cases fit the specific scenario in figure 2. This demonstration and the testing of this study’s hypotheses will be completed through a three-step analysis. The following

section outlines each of the three steps and the factors used in this thesis to determine

31 what constitutes ‘strong’ economic performance and social movements versus ‘weak’ economic performance and social movements.

Method of Analysis and its Underlying Concepts

As mentioned above, contentious politics most commonly arise when people feel deprived of their most basic rights, such as access to food, water, work, or housing.

However, the governments in the western hemisphere agreed in 1994 to form a continent wide free trade agreement that may negatively affect the lives of thousands of people.

Yet, in the case of nations that have indeed seen an increase in their standard of living and experienced modernization and economic growth, people should not have a reason to mobilize against further free trade agreements, unless the economic gains did not trickledown to the rest of society. In order to evaluate that claim, as a first step of the analysis in this thesis, the countries’ economic performance between 1994 and 2005 will be evaluated through the analysis of economic indicators including but not limited to GDP, rate of inflation, unemployment rate, and percent of population living under US$2/day.

These indicators are derived from datasets provided by the World Bank, the Economic

Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC)

, and the United Nations. A more detailed list of the indicators used is included in the appendix. In order to paint a comprehensive picture of the situation of the population and the economic conditions in the analyzed countries, some of the data stems from news and secondary sources providing additional insights and background information. As the analysis will show, out

of the medium size Latin American economies, Chile recorded one of the strongest

32 performances in the region. Similar, as the data provided in chapter four demonstrates, despite the economic meltdown in 2001, the Argentine enjoyed a higher standard of living than most countries in the region. Bolivia and Nicaragua, however, are two of the weakest economies in the western hemisphere. Chapter four will provide a more detailed evaluation of this assessment.

Second, each case will be studied for episodes of contention, social movements or unrests targeting free trade and neoliberal reforms occurring during the FTAA negotiations. Due to the lack of a database tracking domestic social movements, the data for this methodological step mostly stems from secondary sources, such as books and journal articles. Frequently, these works are part of the social movement and contentious politics literature and address more prominent topics such as the emergence and organization of the movement, the formation of its identity, and leadership. However, these sources are used for data regarding the occurrence and frequency of episodes of contention in the respective countries, descriptions of the actors involved and their demands, as well as an account of the events and the repertoire of contention used during these events. In addition, news articles reporting about the events will be reviewed for descriptive evidence.

In order to determine what constitutes strong contentious politics versus weak contentious politics, this study is going to rely on the concepts outlined in the literature review. As pointed out in the previous chapter, the social movements and contentious

politics literature is concerned with what factors lead to the rise of a social movement,

33 what channels and repertoire of contentions are used by the actors, and the impacts of the movement. Other important considerations are who the actors are, how and for how long the movement was able to sustain itself, and how authorities reacted to the public’s mobilization. Episodes of contention in the four countries used as case studies in this thesis will be analyzed and evaluated based on the aforementioned factors, as shown in figure 3. In addition, the analysis will take into consideration the extent of the mobilization in the individual countries. The extent will be assessed by analyzing how many and what types of segments of society participated in the mobilization efforts and whether contention in one sector or one area in the country was able to spark resistance in another. Another indicator for the extent of the mobilization is the participants’ demands.

For example, cases in which the protestors demand the reversal or change of a specific policy in a particular sector, as for example in the education sector in Nicaragua are categorized as weak cases. Countries where the public moved from forming resistance in one particular area to demanding an overall change in the country’s economic policy direction represent cases with strong movements. As the next chapter will demonstrate, this has been the case in Bolivia, where the fight over the country’s natural resources turned into a campaign against the neoliberal economic model itself. Accordingly,

Bolivia represents a case with strong social movements but the contentious politics in

Nicaragua can be classified as weak contentious politics. Further examinations of these

34 factors will be provided in chapter four. This methodological step marks the second part of this study’s three-step analysis.

The third step of the analysis is going to identify each country’s position on the

FTAA. In order to achieve this, news accounts and press releases that quote country officials or trade representatives expressing their respective government’s intention and position in regards to the status of the FTAA negotiations will be reviewed. The data will be gathered through the LexisNexis News database, as well as through the Google News search engine. In order to put the data into context, some of the information will be obtained from secondary sources.

Strong

Movement includes numerous actors; from different paths of lives causes disruption, receives attention and triggers reaction demands radical change in overall policy direction or leadership

Weak

Movement occurs in a specifc area or sector, fails to spark contentious in other areas, consists of small, individual protests; or uses non-disruptive methods demands specific policy changes; does not challenge overall economic model or country's direction

Figure 3: Factors Determining Strength of Contentious Politics

35

Chapter Four

CASE STUDIES

Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to complete the analysis of the four selected case studies according to the principles and methods outlined in the previous section. In order to achieve this objective, each country is going to be evaluated through the following steps. First, the economic performance of the selected countries during the time of the

FTAA negotiation will be assessed. As explained in more detail in chapter three, this step is undertaken in order to assess whether neoliberal policies led to the promised gains, in which case the public would not have had a reason to mobilize against the FTAA. This step is also based on the assumption identified in the literature review that people are more likely to mobilize when they are deprived of their ability to sustain a livelihood, which again closely relates to countries’ economic conditions. The analysis is also going to establish what constitutes ‘strong’ and what constitutes ‘weak’ economic performance for the purpose of this study. After reviewing the countries’ economic performance, this chapter is going to undertake the second step of the analysis outlined in chapter three.

Accordingly, episodes of contention in each of the countries will be analyzed and evaluated according to the criteria outlined in chapter three. The last part of each case study is dedicated to country’s positions on the FTAA. This third step of the analysis will be completed by analyzing claims and statements made by the countries’ governments as

36 reported by international news sources. The final chapter of this thesis provides a comparison of the cases and presents the results obtained in chapter four.

The Case of Argentina

Some readers may wonder why Argentina was chosen as a case study for a country with strong economic performance. The country at the Rio del la Plata has made international news for economic collapses, debt crises, and depressions. Argentina’s economic environment is especially known for its extreme, often unpredictable, fluctuations and volatility (Corcoran 2011). True, Argentina experiences a major economic crisis about once every decade (Corcoran 2011). But as devastating as some of

Argentina’s economic lows might have been, the country’s highs showed characteristics of some of the strongest developing economies (Cline 2004: 1). Throughout most of the

1990s, Argentina recorded episodes of strong economic growth, which created a society with a higher standard of living than in most other countries in the region (Cline 2004: 1).

Argentina’s Economic Performance

Under the rule of President Alfonsín during the 1980s, Argentina experienced high rates of poverty, extreme hyperinflation, corruption, and social exclusion (Salvochea

2008: 296). In order to address these issues, Carlos Saúl Menem turned to implementing the internationally prominent neoliberal economic model after his election in 1989

(Salvochea 2008, Veigel 2009; Silva 2009). Menem became such an advocate for neoliberalism that the country’s new economic policy would become known as

Menemism (Silva 2009: 84). Policies of Menemism included strong structural reforms,

37

“including privatization of state-owned companies, reduction of state-related employment, reform of the welfare system, administrative decentralization, deregulation of economic activities, and the opening of the domestic market to foreign trade and investment” (Villalón 2007: 140).

During the 1990s, Argentina experienced the lowest average rates of inflation and the highest rates of economic growth since the end of World War I (Veigel 2009: 185). This improved economic climate led to a desperately needed increase in foreign direct investment (Veigel 2009: 188). Argentina received more than US$60 billion in gross foreign direct investment, and overall approximately US$100 billion in net capital inflows (Veigel 2009: 188). For the first time in years, Argentina was able to record strong economic growth, high investment rates, and financial stability (Villalón 2007:

140). Because of the improvement in Argentina’s economic performance after the implementation of neoliberal policies, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) declared

Argentina as a role model for so-called emerging economies in 1998 (Veigel 2009: 188).

But around the same time as the IMF and international investors were praising

Argentina’s new trustworthy investment climate that had been created by the neoliberal market policy, domestic organizations started to pay the price of liberalization. Whereas some had declared relief over Argentina’s stable performance during the Mexican crisis that shook the continent during 1994 and 1995, Argentina started to record more than two thousand bankruptcies per year until the ultimate national collapse in 2001 (Veigel 2009:

192). In addition, as the data collected by the IMF shows, unemployment remained high, increasing from seven percent in 1992 (Veigel 2009: 192) to 17.9 percent in 2002

(worldbank.org: GDP growth).

38

In addition, while Argentina recorded some success in battling inflation and the stagnation in economic growth, the country’s performance was lacking when it came to the fight against debt. According to Veigel, public foreign debt significantly increased from US$50 billion in 1994 to more than US$90 billion in 1999, putting a significant damper on the achieved success in terms of economic growth (Veigel 2009: 187). To reduce the country’s deficit, the government started out the new millennium with a sharp tax increase and spending cuts, exacerbating the already desperate situation of the

Argentine people. The decrease in Argentina’s economic performance changed investors’ perception of the country, making it even harder to overcome the acute challenges

(Veigel 2009: 193). Eventually, Argentina experienced its worst economic crisis during

2001 and 2002, notably in the middle of the FTAA negotiations. Klaus F. Veigel provides a snapshot of the state of Argentina at that time:

“Over the course of two years, output fell by more than 15 percent, the Argentine peso lost three-quarters of its value, registered unemployment exceeded 25 percent, and more than half of the population of the once rich country had fallen below the poverty line” (Veigel 2009: 183).

In an attempt to save the poster-child of neoliberal development of the 1990’s from complete collapse, the IMF decided to sit down with the Argentine government and discuss available options (Veigel 2009: 194). The fruit of this collaboration was a stabilization program in which Argentina was to receive US$20 billion, a sum that was meant to display the IMF’s confidence in the nation, hopefully restoring other investors’ trust (Veigel 2009: 194). However, the price did not come without conditions. Argentina had to commit to strong austerity measures in order to cut spending (Veigel 2009: 194).

39

Only a few days after taking office on January 1, 2001, president Eduardo

Duhalde passed the “Economic Emergency Law” which caused many Argentine to see their life savings diminished into a fraction of what it used to be (Veigel 2009: 199).

Simultaneously, inflation rates increased sharply (Veigel 2009: 199). The country recorded a debt of a staggering US$132 billion, marking the largest debt the world has ever seen at that point of time (Corcoran 2011). Given this enormous sum, Argentina’s new administration eventually engaged in debt negotiations with the IMF, achieving that the debt was reduced by one third (Veigel 2009: 200).

After following the neoliberal economic paradigm for a decade, the country experienced complete political, economic, and social collapse at the end of 2001. Even though Argentina is known for its fluctuating economy, the crisis of 2001 marked one of the worst in its history and occurred right after a decade of internationally pushed neoliberal policies. Accordingly, Duhalde and his successor Nestor Kirchner made an effort to break with Menemism (Veigel 2009:200). According to Veigel, this included:

“the proposed nationalization of previously privatized industries, price controls on utilities and public services, and a more active involvement of the state in the economy”

(Veigel 2009:200). Starting in 2003, under the administration of Nestor Kirchner,

Argentina’s economy grew again at the fastest rate since the end of World War I, demonstrating overall strong economic performance (Veigel 2009: 12).

40

Anti-Neoliberal Contention in Argentina

Within a few years, the population could feel significant impacts, economically as well as politically, of Menemism . Argentina was swept by waves of social movements protesting the reconstruction of the state required by the neoliberal paradigm (Silva 2009:

56-68; Villalón 2007: 139). Often referenced as the beginning of the new social movements in Argentina is the Santiagazo town revolt of 1993 (Villalón 2007: 143). That year, on December 16 th , between 3000 and 5000 protesters took the streets in the province of Santiago del Estero, protesting the structural adjustment programs and ongoing governmental corruption. Joining their forces were people from all paths of lives, including teachers, students, union leaders, and government employees. The episode of contention lasted for two days and resulted in the invasion, looting, and burning down of three government buildings and the residents of local officials and politicians (Auyero 2003: 37). Over the next few years, similar town revolts occurred throughout the country. In 1994, the episodes of contention occurred in the provinces of

La Roja, Salta, Chaco, Entre Rios, and Tucuman. Similar events have been recorded in

1995, in San Juan, Cordoba, and Rio Negron and in 1999 in Corrientes (Villalón 2007:

143). According to Villalón, the contention was mostly driven by “public-sector workers

[responding to] the reduction of state employment by provincial and municipal governments under structural reform policies” (Villalón 2007: 143). Villalón points out that none of these events had been organized by traditional contentions politics representatives such as unions or political parties (Villalón 2007: 144). Whereas

traditional social movements in Argentina were usually organized events driven by

41 unions or other labor groups, episodes of anti-neoliberal contention in Argentina frequently emerged without leadership contesting specific policies or policy impacts

(Villalón 2007: 140). The social movements occurring in Argentina during the 1990s therefore fulfill the description of the “new social movement” as identified in the literature review.

Despite the revolts, the Argentine government continued to follow the neoliberal paradigm. Accordingly, the Argentine people moved toward more sustainable methods of protest, such as organizing roadblocks and picketing (Villalón 2007: 144). This included preventing normal traffic to and from major cities, causing the disruption of the free movement of people, goods and services. Frequently, this was achieved through the use of objects that were difficult to move, such as burning tires or large vehicles, alongside masses of protestors (Villalón 2007: 144).