Document 16058177

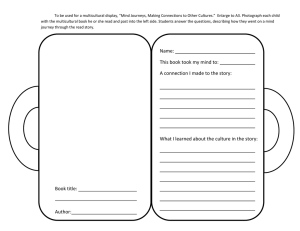

advertisement