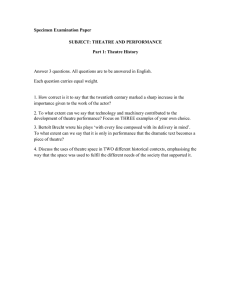

Chapter 1 THE INTRODUCTION OF PLAY AND PERFORMANCE

advertisement