Access Control Michelle Mazurek Usable Privacy and Security October 29, 2009

advertisement

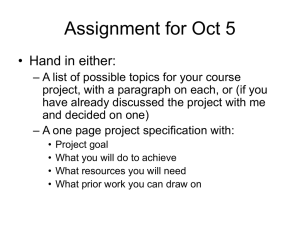

Access Control Michelle Mazurek Usable Privacy and Security October 29, 2009 Outline • How do people think about access control? • What and when do they want to share? • How do people use current standard access control mechanisms? • Discussion: System design guidelines 2 Thinking about sharing • Olson, Grudin, and Horvitz: A study of preferences for sharing and privacy • Ahern et al.: Privacy patterns and considerations in online photo sharing • Recent study by home security team: Attitudes, needs and practices for home data sharing 3 Mapping detailed preferences • Overview survey: “A situation in which you or another person did not wish to share information.” • Selected 19 types of people, 40 types of files • Detail survey: 30 participants filled out the resulting grid • How comfortable sharing? 1 to 5 (or n/a) • Instantiate each type of person Olson, Grudin, Horvitz, 2005 4 Types of people • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Best friend Spouse Parent Sibling Adult child Young child Extended family Personal website Salesperson Trusted colleague Manager Subordinate Corporate lawyer Competitor Company newsletter People you want to impress • Other team members 5 Types of information • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Current location Current IM status Buddy list Calendar entries Web history Phone, e-mail Age Health status Credit card number 6 Work in progress Finished work Successes, failures Performance review Salary E-mail content Social Security # Politics/religion New job application Results – Sharing preferences People: High to Low • Spouse, best friend, parent • Extended family, subordinate, team members • Competitor, personal website, salesperson Info: High to Low • Work e-mail, desk phone, cell phone, age, marital status • Health status, politics/religion, work in progress • Transgression, email content, credit card, SSN 7 Results – Variation in variance • No variance: • Always share: work e-mail address, phone # with spouse, co-workers • Always share: home phone # with spouse, children • Never share: credit card number with the public • Lots of variance: • • • • Personal items with co-workers (age, health, etc.) Credit card with parents, grandparents Pregnancy status with siblings Work documents with family members 8 Variation among people • Unconcerned, pragmatists, fundamentalists • Overall, restrict more than share 9 Clustering people and information • Manager, trusted colleague • Best friend, family • Other co-workers • Spouse • General public • E-mail content, credit card #, transgression • Failures, salary, SSN • Home, cell number; age; marital status; successes • Health, religion, politics • Work-related stuff • Work e-mail, phone # 10 Mapping clustered preferences 11 Discussion and guidelines • One size doesn’t fit all, but strong clustering implies manageable categories • Recommend policy configuration at multiple precision levels • Recommend statistical prediction (dynamic cluster analysis) 12 Privacy in online photo sharing • Collected and analyzed data from 5 months of real use of Flickr with ZoneTag • 81 users, uploaded at least 40 photos each • 36,915 total photos • Followed up by interviews with users about their access control decision-making • Recruited social groups of non-technical people • 15 participants, not previous Flickr users • Provided phone, data plan, Flickr Pro; used their own SIM cards Ahern et al., 2007 13 Flickr and ZoneTag Flickr • Public vs. non-public (private, family, friends) • Public photos are searchable (text labels) ZoneTag • Cameraphone app for upload to Flickr • By default, repeat most recent privacy setting • User can modify as desired • Add tags (suggestions, quick entry) • Location tags added automatically 14 Does location predict privacy? • H1: Some locations are more public than average; others are more private • Calculate ratio of public photos to total photos • For all photos, then individually per location 0.25 Very Private 0.1 0.1 0.25 Private Typical Public Very Public • 50% of users: fewer than half “typical” photos • 19 users: more than half “very” photos 15 Does location predict privacy? • H2: More frequent locations are more private • Calculate ratio as before; sort by frequency • Found significant correlation 16 Does content predict privacy? • Hand-classified 1400 frequently-used tags • Person, location, place, object, event, activity • Calculate public: non-public per category • Person significantly more private than rest • Activity significantly less private than average 17 Additional quantitative analysis • Access setting changed after upload: 7% • Decisions are not often strongly regretted • May be related to misuse of default • Location information suppressed: 2% • Perhaps no concern about zip-level location sharing • Perhaps because users don’t know how to suppress it 18 Interview results • Conducted after 2 weeks of system use • Four major themes emerged: 19 Results: Security • Location – near real-time whereabouts • “If I did something to upset somebody somehow … and they knew exactly where I lived by looking at my Flickr photos, that would bother me.” • Especially with regard to children • Both content and location • Fits with quantitative analysis • Person is more private (children) • Some locations (home?) are more private 20 Results: Identity, Social Disclosure Identity • Image content may be unflattering to user, others • May expose private interests Social Disclosure • If someone wasn’t invited • When friends are “doing their, uh, ‘musician things’ … don’t need any incriminating evidence.” • Conservative family, pride parade photos 21 Results: Convenience • Using access controls requires friends, family to sign up for Flickr accounts • Sometimes it’s easier just to make it public • Sometimes users want to make certain photos available to friends of friends 22 Results: Location privacy • Showed participants their aggregate location data • Generally unconcerned at zip granularity • Worries about advertisers • Changes from pre-study interview • 17% said would never share • 50% would share under special circumstances • In reality, every person shared and no one suppressed 23 Results: Other factors • Making decisions at capture time • Unsure how photos will look on the web • Unsure about subject’s preferences • Limiting complexity • Often choose the default for minimal effort • Dissatisfaction • Unhappy with all available options • Choose the best available but remain frustrated 24 Discussion and guidelines • Desired privacy settings often correlate with location and with content of tags • Suggestions: • Use these patterns for prediction, recommendation, or warning of possible errors • Make aggregate disclosure visible to users • Provide social comparison (similar decisions made by friends) to reveal relevant norms • Show users how others will view the photos 25 Further guidelines • Decouple visibility from discoverability • Public settings so no need to register • Not searchable so disclosure may be limited • Decouple photo and location visibility • Independent location disclosure settings • Encourage a range of access control settings • Self-censoring limits usage • Maximizing public photos adds value to system owner 26 Exploring access control at home • Goal: Understand how people think about access control • Wanted to examine several different facets • Current practices: digital, paper • Different policy dimensions: person, location, device, presence, time of day • Additional features: Logs, reactive policy creation Mazurek et al., 2009 http://www.pdl.cmu.edu/ 27 Michelle Mazurek © Oct 09 Designing a user study • In-situ interviews • Recruitment via Craigslist, flyers • Limited to non-programmer households • Interview family members at home: together, then individually • Semi-structured interviews • Elicit information about people, files • Ask specific questions as jumping-off points • Continue with free-form responses http://www.pdl.cmu.edu/ 28 Michelle Mazurek © Oct 09 Question structure • For each dimension, start with a specific scenario • Imagine that [a friend] is in your house when you are not. What kinds of files would you (not) want them to be able to [view, change]? • Would it be different if you were also in the [house, room]? • Extend to discuss that dimension in general • Rate concern over specific policy violations: • 1 = don’t care to 5 = devastating http://www.pdl.cmu.edu/ 29 Michelle Mazurek © Oct 09 Data analysis • Initial rough analysis identified areas of interest; fed back into later interviews • Iterative topic and analytic hand coding – loosely based on Grounded Theory1 • Searchable database format • Combine codes to develop broader theories; revisit data as needed • Results are qualitative 1Razavi http://www.pdl.cmu.edu/ 30 and Iverson, 2006 Michelle Mazurek © Oct 09 Study demographics Households People Families 6 16 Couples 5 10 Roommates 4 11 Total 15 37 • Ages 8 to 59 • Wide range of computer skills http://www.pdl.cmu.edu/ 31 Michelle Mazurek © Oct 09 Household devices • Common devices: Laptop, desktop, DVR, iPod, cell phone, digital camera • Minimum: 1 desktop, 1 mobile phone, 3 iPods for a family of four • Maximum: 22 devices for 3 roommates • • • • • 3 laptops, 2 desktops 3 cell phones Still and video cameras Video game systems USB sticks, memory cards, external hard drives http://www.pdl.cmu.edu/ 32 Michelle Mazurek © Oct 09 Four key findings 1. People have important data to protect, and the methods they currently use don’t provide enough assurance 2. Policies are complicated 3. Permission and control are important 4. Current systems and mental models are misaligned http://www.pdl.cmu.edu/ 33 Michelle Mazurek © Oct 09 F1: Current methods aren’t working • People worry about sensitive data • Many potential breaches rated as “devastating” • Almost all worry about file security sometimes • Several have suffered actual breaches • Mechanisms vary (often ad-hoc) • Encryption, user accounts (some people) • Hide sensitive files in the file system • Delete sensitive data so no one can see it “If I didn’t want everyone to see them, I just had them for a little while and then I just deleted them.” http://www.pdl.cmu.edu/ 34 Michelle Mazurek © Oct 09 F2: Policy needs are complex • Fine-grained divisions of people and files strangers teacher boss friends parents boyfriend • Public, private aren’t enough • More than friends, family, colleagues, strangers • One policy: shared mixed restricted music photos private docs study abroad docs schoolwork work files other docs http://www.pdl.cmu.edu/ 35 Michelle Mazurek © Oct 09 F2: Dimensions beyond person • Read vs. write remains important • Read-only is needed but not sufficient • Presence resonated for most • “If you have your mother in the room, you are not going to do anything bad. But if your mom is outside the room you can sneak.” • Also can provide a chance to explain • Location • People in my home are trusted • Higher level of “lockdown” when elsewhere • Device, time of day not as popular http://www.pdl.cmu.edu/ 36 Michelle Mazurek © Oct 09 F2: Variation across participants • Finding reasonable defaults is difficult • What is most/least private? • Sharing-oriented vs. restriction-oriented • “Basically, it’s my stuff; if I want you to have it, I’ll give it to you.” • “I don’t really have private files.... There’s nothing that I am hiding from anybody.” • Most have one “most trusted” person • Definition of “most trusted” varies widely http://www.pdl.cmu.edu/ 37 Michelle Mazurek © Oct 09 F3: Permission and control • People like to be asked permission • Positive response to reactive policy creation • “I’m very willing to be open with people, I think I’d just like the courtesy of someone asking me.” • Setting policy ahead of doesn’t convey control like being present and/or explicitly granting permission • If I’m present, “I can say, ‘These are the things that you could see’.” • “I can’t be giving you permission while I sleep because I am sleeping.” http://www.pdl.cmu.edu/ 38 Michelle Mazurek © Oct 09 F3: A-priori policy isn’t enough • Last-minute decisions • Review logs and fine-tune: • “If someone has been looking at something a lot, I am going to be a little suspicious. In general, I would [then] restrict access to that specific file.” • People want to know why as well as who • “I might be worried about who else was watching.” • “From my devices they would be able to view it but not save it.” http://www.pdl.cmu.edu/ 39 Michelle Mazurek © Oct 09 F4: Mental models ≠ systems “If anything were to happen, ... I’m right there to say, ‘OK, what just happened?’ So I’m not as worried.” • Desktop search finds “hidden” files • Being present isn’t enough • Violations can happen too fast to prevent • Can’t necessarily monitor across the room • Files can be shared across devices; files within a device can be restricted • “In my house” maybe not a good trust proxy • Seems natural but fails after more thought http://www.pdl.cmu.edu/ 40 Michelle Mazurek © Oct 09 Resulting design guidelines • Allow fine-grained control • Specification at multiple levels of granularity to support varying needs • Plan for lending devices • Limited-access, discreet guest profiles1 • Include reactive policy creation • “Sounds like the best possible scenario.” • “It would be easy access for them while still allowing me to control what they see.” 1Karlson http://www.pdl.cmu.edu/ 41 et al., 2009 Michelle Mazurek © Oct 09 More design guidelines • Reduce or eliminate up-front complexity • “If I had to sit down and sort everything into what people can view and cannot view, I think that would annoy me. I wouldn’t do that.” • Reactive policy creation can help with this • Support iterative policy specification • Interfaces designed to help users view/change effective policy, not just rules • Include human-readable logs http://www.pdl.cmu.edu/ 42 Michelle Mazurek © Oct 09 Even more guidelines • Acknowledge social conventions • Requesting permission (reactive creation again) • Plausible deniability: “I don’t want people to feel that I am hiding things from them.” • Account for users’ mental models • A lot of mismatches come from incorrect analogies to physical systems • Either fit into existing models or explicitly guide users to new mental models http://www.pdl.cmu.edu/ 43 Michelle Mazurek © Oct 09 Access control in practice • Smetters and Good: How Users Use Access Control • Collect usage history data from 200employee corporation • Examine Windows and Unix user groups • Examine e-mail lists • Majority of document sharing is by e-mail • Examine DocuShare usage • File permissions • Snapshots a year apart Smetters and Good, 2009 44 Analyzing groups • • • • Group name List of members (users and groups) Owner, create time, modify time Who can update membership? 45 Results – group membership • Most groups have fewer than 20 members • Users participate in more groups when groups are user-defined (not administrators) • Membership changes on order of months, years System Avg. Users/Group Avg. Groups/User Max Groups/User Windows 6.3 3.7 35 Unix/NFS 7.0 4.2 16 DocuShare 11.9 7.8 30 Mailing lists 14.2 9.3 411 46 Results – Group construction • Users more often add members; administrators more often “clean up” • User-defined groups are more often disorganized, duplicate • Windows groups with clear structure, naming convention • DocuShare groups with overlapping and misleading names • Unix “emergency” groups with misspelled usernames 47 DocuShare settings • • • • List of ACLs to users or groups Positive rules only (no deny rules) Files have single owners with full rights Policy inheritance: folder policy automatically applies to documents added to that folder • Inheritance prompt when folder settings change 48 DocuShare data • Collected files and folders visible to 8 users • 49,672 unique objects (documents or folders) • Consider how many users can see each item Type Percent # Users # Items File 72.7 1 3375 Folder 14.3 2 762 URL 6.7 3 250 Event 5.7 4 57 Calendar 0.2 5 1742 Bulletin board 0.1 6 40 7 877 8 42569 49 Results – Setting permissions • 5.2% of objects had permissions different from their parent • 3.5% of all documents; 15% of all folders • Among changed items: • 52% different list of principals • 30% different permissions for a given principal • 17% both • Claim: In general users prefer to add files to pre-set folder rather than set permissions 50 Results – ACL contents • Consider only “explicitly set” lists • 4527 user rules; 4755 group rules • 22% read-only rules; 73% read-write rules • Complex ACLs are common • Only 3.9% contain exactly one group 51 More about ACL contents • Users are often double-listed: individually and as part of a listed group • All cases with 17 or more individuals • Almost nothing is private to owner (8 docs) • Lots of things are “public” • 22% readable by built-in “everyone” • 86% readable by local “authorized users” • May be a function of DocuShare usage model, and/or this organization’s open culture 52 Discussion and guidelines • Simplify access control • Positive rules only – Negative rules are complex and hard to parse – Same goal can be achieved with better groups • Simplify inheritance – Don’t force users to choose • Limit permission types – Do we need anything beyond read, write, exec? 53 Further guidelines • Let users create their own groups • Good groups make specifying good policy easier • But earlier, disorganized groups are dangerous? • Better management tools • • • • • Group management: reduce redundancy ACL management: promote groups over users Cleanup management: prune outdated items Intelligent activity-based grouping Effective policy visualizations 54 Overview of guidelines • Multiple-precision policy configuration • Statistical policy recommender systems • Person and file clustering • Location- and content-based • To predict policy or warn about possible errors • Make aggregate disclosure visible • Provide comparison to social norms • Show the user what others will see 55 Overview of guidelines 2 • Decouple policy for different information types • Search vs. access, photo vs. location, etc. • • • • • • • Encourage users to get beyond defaults Allow fine-grained control Plan for lending devices Include reactive policy creation Reduce up-front complexity Support iterative policy specification Acknowledge social conventions 56 Overview of guidelines 3 • • • • • Account for mental models Positive rules only Simplify policy inheritance Limit permission types Promote use of groups in access lists • Let users create their own groups • Tools to reduce redundancy and promote cleanup • Activity-based suggestions • Effective policy visualizations 57