Scanner’s note:

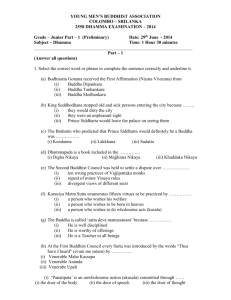

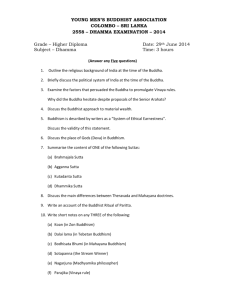

advertisement