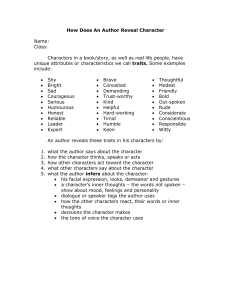

Thinking and Speech. Lev Vygotsky 1934

advertisement