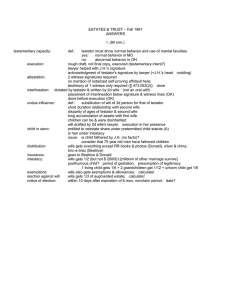

Misty Watson Trusts and Estates Prof. Rosenbury Fall 2005 I. Introduction

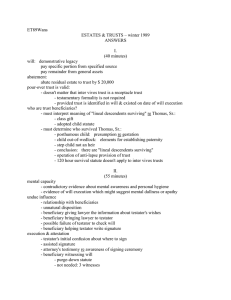

advertisement