Document 15964665

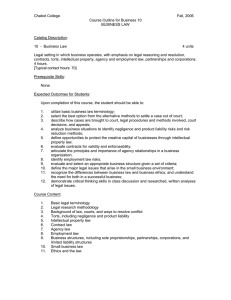

advertisement