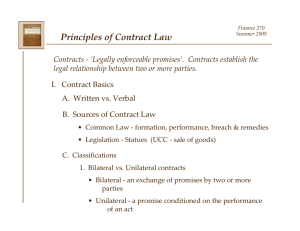

A promise or set of promises, for breach of which... Three types of contracts: What is a Contract?

advertisement