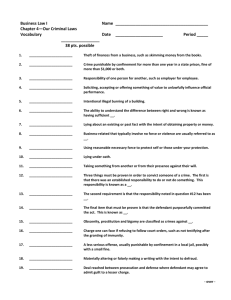

Criminal Law Outline Brickey 2002 Defining Criminal Liability

advertisement