To define the mission, vision, philosophy, and principles of... development and instructional delivery for competency-based educational Competency-Based Education Framework

advertisement

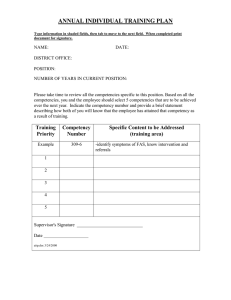

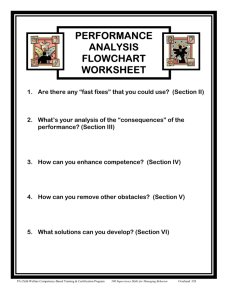

Competency-Based Education Framework Davenport University August 18, 2015 I. Purpose of Document To define the mission, vision, philosophy, and principles of curriculum development and instructional delivery for competency-based educational approaches at Davenport University To provide academic guidelines, policies, and processes for the development and implementation of new CBE approaches at Davenport II. Why Davenport University Supports CBE Davenport’s VISION 2020 states that central to the university’s success is “its ability to provide students with an education that equips them with the knowledge, global competencies and values they need to achieve their career and life goals” (Davenport University, Vision 2020, 2015, p. 1). CBE is directly connected to the following core elements of VISION 2020: Increasing student satisfaction by providing a “high degree of flexibility and engagement that enhances the learning experience…and [allowing] students to change course…without adding time toward degree completion” (p. 1). Exploring “use of accelerated formats such as three-year baccalaureate degrees and competency-based education that will allow students to complete degrees more quickly, based on their abilities” (p. 1). Providing “high levels of accountability [and] partnering with businesses, healthcare organizations, and school districts [to] result in employer satisfaction scores at the highest levels in the institution’s history” (p. 2). DU also supports CBE because it can: III. Reduce time to degree completion and overall cost to the student Allow maximum application of Credit for Prior Learning Serve all students, but particularly non-traditional students, who have relevant career experience Context for CBE CBE is a constantly changing landscape nationally and it has significantly different implications for implementation than traditional academic programs, particularly in terms of financial aid, billing, contact hours, etc. Any new DU CBE course or program should consider these implications and consult the appropriate functional areas of the university early in the development process. Additionally, as proposed DU CBE programs gather data on their target market, they should consider that CBE research indicates that successful CBE students are: W. Sneath/ J. Byron/G. Nyambane: August 2015 2 Highly motivated and self-directed with strong self-discipline and organizational skills Focused on career development, with a clear sense of purpose and direction, and are willing to explore non-traditional learning paths Comfortable with technology and savvy regarding the ability of technology to enhance learning in their lives Open to new experiences and willing to risk trying something new (Klein-Collins, R. & Baylor, E., 2013 & Davenport University, CMBA FAQs, 2015) IV. Definitions of Competency-Based Education While there are varied and emerging definitions of CBE, Davenport’s participation in the Competency-Based Education Network (C-BEN), a nationally recognized organizational leader in the CBE movement, supports a working definition of CBE in alignment with CBEN’s: “Competency-based education (CBE) is a flexible way for students to get credit for what they know, build on their knowledge and skills by learning more at their own pace, and earn high-quality degrees, certificates, and other credentials that help them in their lives and careers. CBE focuses on what students must know and be able to do to earn degrees and other credentials. Student progress is measured by their demonstration of competencies, or mastery of required learning, through assessments that are embedded in courses, modules, and other structured learning experiences. Students move ahead as they prove they have mastered the knowledge and skills required for a particular area” (Competency-Based Education Network, 2014, p. 1). Importantly, for reference, the U.S. Department of Education and the Council of Regional Accrediting Commissions’ definitions of competency-based education are included in Section VII: Operational Definitions of this document. V. Curriculum Principles for Competency-Based Education When designing new CBE courses and programs, faculty should consider the following four essential curriculum principles: 1. Define valid and rigorous competencies Competencies should include explicit, measurable, and transferable learning objectives which are clearly articulated to students (Iowa Department of Education, 2015, p. 1). Competencies should emphasize the application of learning. A high quality competency-based approach will require students to apply skills and knowledge to new situations to demonstrate mastery and to create knowledge. Competencies will include academic standards as well as lifelong learning skills and dispositions 3 and are often framed as “can do” statements (Competency Based Pathways, n.d., para. 5). Competencies should reflect the skills and knowledge that students will need at the next stages of their development, whether it be further education or employment (Johnstone & Soares, 2014, p. 5). The validity of competencies should be determined by student and employer feedback to faculty and program designers (p. 5). The process for developing program-level competency definitions should be iterative, evolving to incorporate marketplace demands, academic expectations, and student needs (p. 5). 2. Design instruction for individualized student pacing and completion Students work at levels that are appropriately challenging (Competency Based Pathways, n.d., para. 1). Students progress to more advanced work upon demonstration of learning by applying specific skills and content (para. 1). Students master subjects at different rates and bring diverse levels of prior experience and knowledge to that mastery (Competency-Based Education Network, 2014, p. 1). Students receive timely, differentiated support based on their individual learning needs (Competency Based Pathways, n.d., para. 4). CBE programs should enable students to move through courses more quickly than they would in traditional online or face-to-face courses (Mathematica Policy Research, 2015, p. 2). Faculty guide students to produce sufficient evidence to demonstrate competency (Competency Based Pathways, n.d., para. 1). Faculty must have a rapid response capacity to support students when they are struggling to meet a competency (para. 4). Faculty should consider technology-enabled solutions that incorporate predictive analytic tools to assist in student support (para. 4). Differentiated student learning plans should be used to capture knowledge on learning styles, context and interventions that are most effective for individual students (para. 4). 3. Develop quality learning resources with 24/7 availability Learning materials must be of high quality: accurate, engaging, at the appropriate level of difficulty, well-matched to competencies and compatible with the institution’s technology platform (Johnstone & Soares, 2014, p. 7). Effective learning resources should be available any time and are reusable beyond a single semester or unit of instruction in order to test and improve their validity and reliability (p. 7). Units of learning are scaffolded to build greater levels of skill, but do not have to be completed sequentially; they can stand alone as sub-components of a 4 competency. Learning may occur through in-seat group activities, individualized student study, faculty mentoring and tutoring, self-directed online materials and activities, etc. (Iowa Department of Education, 2015, p. 5). 4. Create multiple forms of valid and reliable assessment clearly mapped to competencies VI. CBE should include formative assessments which evaluate learning progress during the instructional process; students receive immediate feedback when assessment occurs; formative-assessment information is used to inform instructional adjustments, practices, and support (Competency Based Pathways, n.d., para. 3 & Sturgis, 2014, para. 7). Summative assessments should evaluate competency; summative-assessment scores record a student’s level of competency at a specific point in time (Sturgis, 2014, para. 8). Faculty should assess competencies in multiple contexts and in multiple ways; assessments can take many forms, from demonstrations to research papers to objective tests, etc. (Competency Based Pathways, n.d., para. 1 & (Johnstone & Soares, 2014, p. 8). Faculty must collaborate to develop understanding of what is an adequate demonstration of competency (Competency Based Pathways, n.d., para. 3). All assessments must be secure and reliable (Johnstone & Soares, 2014, p. 8). Operational Definitions Assessment Authentic Assessment Authentic assessment is the assessment of competencies in a manner that as closely as possible approximates the way in which that competency will be demonstrated in the individual’s professional and/or civic life (Everhart, Sandeen, Seymour & Yoshino, 2015, p. 8). Direct Assessment Direct assessment refers to the use of academic assessment methodologies for evidence-based evaluation of student competencies, rather than evaluation based on indirect measures such as the student’s seat time in the classroom. In competency-based education, tests, rubrics, and other assessment measures can be aligned with specific competencies for evaluation of competency mastery (Everhart, Sandeen, Seymour & Yoshino, 2015, p. 8). Formative Assessment Formative assessment is an evaluation of student learning during the progression of a module or learning activity to improve student performance. Formative assessment supports students through constructive feedback by: 1) diagnosing student difficulties; 2) measuring improvement over time; and 3) providing 5 information to inform students about how to improve their learning. Formative assessments are generally low-stakes, which means that they have low or no impact on summative evaluation of competency (Dardin, 2015, p. 1 & Carnegie Mellon University, 2015, para.1). Summative Assessment Summative assessment is an evaluation of competency at the end of a module or learning activity by comparing it against standards or benchmarks to meet accountability demands. Summative assessment reflects the culmination of the scaffolding process of learning provided by formative assessment throughout the module/activity. When used for improvement, summative assessment impacts the next cohort of students taking the module or participating in the learning activity. Summative assessments are usually high-stakes, which means that they determine acceptable levels of competence to move on to subsequent competencies (Dardin, 2015, p. 1 & Carnegie Mellon University, 2015, para.1). Prior Learning Assessment Prior Learning Assessment (PLA) is the assessment of an individual’s life learning for college credit, certification, or advanced standing toward further education or training based on their learning gained outside a traditional academic environment such as working, participating in employer training programs, serving in the military, studying independently, volunteering or doing community service, and studying open source courseware. PLA can be used in conjunction with modular approaches to CBE (CAEL, 2015, para. 1). Competency A competency is a specific skill, knowledge, or ability that is both observable and measurable (Everhart, Sandeen, Seymour & Yoshino, 2015, p. 5). Competency-Based Education U.S. Department of Education Definition: “According to the U.S. Department of Education (n.d.), competency-based learning or personalized learning is a structure that creates flexibility, allows students to progress as they demonstrate mastery of academic content, regardless of time, place, or pace of learning. Competency-based strategies provide flexibility in the way that credit can be earned or awarded, and provide students with personalized learning opportunities. These strategies include online and blended learning, dual enrollment and early college high schools, project-based and community-based learning, and credit recovery, among others. This type of learning leads to better student engagement because the content is relevant to each student and tailored to their unique needs. It also leads to better student outcomes because the pace of learning is customized to each student (para 1)” (as cited in Dawson, Dean, Johnson & Koronkiewicz, 2014, p. 1). 6 Council of Regional Accrediting Commissions’ Definition: “Competency-based education (CBE) is an outcomes-based approach to earning a college degree or other credential. Competencies are statements of what students can do as a result of their learning at an institution of higher education. While competencies can include knowledge or understanding, they primarily emphasize what students can do with their knowledge. Students progress through degree or credential programs by demonstrating competencies specified at the course and/or program level. The curriculum is structured around these specified competencies, and satisfactory academic progress is expressed as the attainment or mastery of the identified competencies. Because competencies are often anchored to external expectations, such as those of employers, to pass a competency students must generally perform at a level considered to be very good or excellent” (Council of Regional Accrediting Commissions, 2015, p. 2). Differentiated Instruction Differentiated instruction refers to a variety of methodologies that direct students along different pathways based on their needs and mastery of competencies. Differentiated learning often “branches” different learning materials, interventions, feedback, diagnostic measures, and/or adaptive structures based on an individual student’s progress or characteristics that put them in a defined grouping (Everhart, Sandeen, Seymour & Yoshino, 2015, p. 6). Direct Assessment Program Direct assessment program is federally defined as “an instructional program that, in lieu of credit hours or clock hours as a measure of student learning, utilizes direct assessment of student learning, or recognizes the direct assessment of student learning by others, and meets the conditions of 34 CFR 668.10. For Title IV, HEA purposes, the institution must obtain approval for the direct assessment program” (as cited in Everhart, Sandeen, Seymour & Yoshino, 2015, p. 18). Mastery Mastery is a high-level demonstration of a specific competency. Mastery of specified competencies in competency-based education is the mechanism by which a student progresses through the educational process to the desired end state (Everhart, Sandeen, Seymour & Yoshino, 2015, p. 8). Module A discrete segment of learning including a cluster of exercises and activities that build knowledge and/or skills in a specific subject or knowledge domain. Modules often include activities and exercises as well as pre, formative, and summative (final) assessments for demonstration of competency. 7 Proficiency Proficiency signifies achievement within an educational program context. Levels of proficiency are determined by the education provider and sought by the student in the program. Proficiency in all program areas is the ideal goal. In competency-based education, “proficiency” is usually a level of achievement that is considered “passing” (e.g. 60%), but a higher level of achievement (e.g. 85%) is required for mastery and progression through the program (Everhart, Sandeen, Seymour & Yoshino, 2015, p. 9). Self-Paced Learning Self-paced learning allows students to progress through learning materials and processes more quickly or more slowly on their own terms, including the ability to set their own deadlines and completion goals, generally without externally-defined constraints (Everhart, Sandeen, Seymour & Yoshino, 2015, p. 7). References Book, P. (2014). All Hands on Deck: Ten Lessons from Early Adopters of Competency-Based Education. Retrieved from http://wcet.wiche.edu/wcet/ docs/summit/AllHandsOnDeck-Final.pdf Carnegie Mellon University. (2015). What is the difference between formative and summative assessment? Retrieved from https://www.cmu.edu/teaching/assessment/basics/formativesummative.html Competency-Based Education Network. (2014). What is CBE? Retrieved from http://eventmobi.com/api/events/9209/documents/download/5e2c4393-2a4f-4eb9-b27e9004eaa0c0ff.pdf/as/What%20is%20CBE%20&%20C-BEN? Competency-Based Pathways. (n.d.). 5 Design Principles from Competency Based Pathways: Detailed Definition of Competency-based Pathways. Retrieved from https://sites.google.com/site/ competencybasedpathways/home/understandingcompetency-based-approaches/definition 8 Council of Regional Accrediting Commissions. (2015). Statement of the Council of Regional Accrediting Commissions (C-RAC) Framework for Competency-Based Education. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/sites/default/server_files/files/CRAC%20CBE%20Statement%20Press%20Release%206_2.pdf Council for Adult and Experiential Learning. (2015). What is Prior Learning Assessment? Retrieved from http://www.cael.org/pla.htm#What%20Is%20Prior% 20Learning%20Assessment%20(PLA)? Darden, A. (2015). Moving SoTL Projects Forward: Applying what you already know and do to SoTL - Methodologies and Literature Searches. Retrieved from http://www.creighton.edu/fileadmin/user/CASTL/Darden_CASTL_handout09.doc. Davenport University. (2015). CMBA FAQs. Retrieved from http://www.davenport.edu/ donald-w-maine-college-business/competency-based-education/cmba-faqs Davenport University. (2015). Vision 2020. Retrieved from http://www.davenport.edu/ aboutdavenport/vision-2020 Dawson, D., Dean, J., Johnson, E. & Koronkiewicz, T. (2014). Competency-Based Education: Closing the Completion Gap. At Issue 4(1). Retrieved from http://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/administration/academicaffairs/extendedinternational/ccle adership/alliance/documents/AtIssue_Competency-Based-Education_2014-03March.pdf Dilmore, T., Moore, D., & Zuleikha, J. (2011). Implementing Competency-Based Education: A Process Workbook 2009-2011. Retrieved from http://www.academic.pitt.edu/ assessment/pdf/CompetencyBasedEducation.pdf Everhart, D., Sandeen, C., Seymour, D. & Yoshino, K. (2015). Clarifying Competency Based Education Terms. Retrieved from http://app.email.blackboard.com/e/er?s= 2376&lid=14837&elq=00000000000000000000000000000000 9 Iowa Department of Education. (2015). Guidelines for PK-12 Competency-Based Education. Retrieved from https://www.educateiowa.gov/sites/files/ed/documents/Competencybased%20Guidelines2015-06-17.pdf Johnstone, S. & Soares, L. (2014). Principles for Developing Competency-Based Education Programs. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 46:2, 12-19. doi: 10.1080/00091383.2014.896705 Klein-Collins, R. & Baylor, E. (2013). Meeting Students Where They Are: Profiles of Students in Competency-Based Degree Programs. Center for American Progress and the Council for Adult and Experiential Learning. Retrieved from http://www.wgu.edu/wgufiles/pdf-caelarticle-11713. Mathematica Policy Research. (2015). Best Practices in Competency-Based Education: Lessons from Three Colleges. Retrieved from http://www.mathematica-mpr.com/~/ media/publications/pdfs/education/cbe_bestpractices_ifbrief.pdf Sturgis, C. (2014). 10 Principles of Proficiency-Based Learning. Retrieved from http://www.competencyworks.org/resources/10-principles-of-proficiency-based-learning/