Document 15951632

advertisement

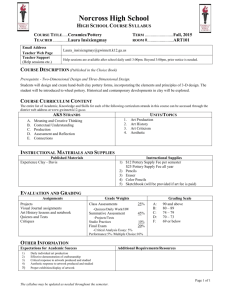

Let’s begin with a few definitions, idiosyncratic though they may be. Definitions: Archaeology Archaeology, at it’s most basic is simply digging interesting things out of the ground. In some cases, when certain constraints I mention later are in effect, it may be limited to picking up interesting things from the ground, although we were all taught as children never to do that. As an autobiographical aside, it occurs to me that my interest in archaeology is entirely a reaction to a childhood of being told, “Don’t pick that up!” Weller Dickensware II Vase Zanesville, Ohio, ca. 1910 In any case, I stress the word “interesting.” To an archaeologist for an item to be “interesting” it must have the potential to provide information about the person or persons who made it, used it, bought or sold it, broke, it and through it away, as well as more abstract information about why they did those things. Artifacts are nothing more nor less than bits of data. Because of this, the reasons for the archaeologist’s inherent interest in ceramics should be obvious. “AH broken is the golden bowl! the spirit flown forever!”-Edgar Allan Poe, "Lenore," The Raven and Other Poems, 1845 Arc-en-Ceil Pottery, Zanesville, Ohio, ca. 1905 The brutal truth is that archaeologists usually prefer the broken bowl, not just so that they have something to do gluing the sherds back together but because pottery, though fragile when whole, paradoxically becomes almost indestructible once it is broken. It may be broken in to smaller and smaller pieces, but these pieces tend to be very resistant and inert. Also, since pottery is entirely artificial and is formed to the creator’s whim, it tends to vary greatly, within certain utilitarian limits. Because it usually presents a plain surface ideal for decoration , it is often further modified by painting or other means of decoration. So, while essentially utilitarian in nature, pottery practically begs to be turned into art, and we see through the course of even its brief history in Ohio an increasing tendency for the artistic impulse to overtake the utilitarian. When that actually happens— and we can pinpoint it to about 1876— art pottery is born. It May be Pottery but is it Art? A few examples of the variety of Ohio ceramics, roughly in the chronological order in which the dominated the Ohio ceramic scene: Utility Ware T.J. Wheatley Faience Windowbox Cincinnati 1880 Art Pottery T. Reed Stoneware Jar Tuscarawas Co. ca.1865 Art China Novelty China Ware Grindley Ware Elephant Bank Sebring, Ohio, ca. 1945 Clarus Ware Coshocton 1905 Why Ohio? Ohio can be defined in many ways— politically, for example, as “the home of the Taft family—but in terms of pottery, it is definitely “The Pottery Center of the World,” although Zanesville and East Liverpool may continue to argue about which city is the pottery center of Ohio. Reasons for this dominance in ceramics are geologic, geographic, and economic: an abundance of high-quality clays in the bedrock of southeastern Ohio, cheap fuel in the form of (initially) timber and (later) coal, natural gas, and petroleum. The decline of ceramics production in Ohio is also due to economic factors—cheap foreign imports—dare we mention Noritake?”—the introduction of plastics—a material not only more plastic but cheaper than clay-- and changes in taste or popularity. Ohio: Pottery Center of the World Clay, Fuel, Market, Transportation High grade fire clay along I-70 West of Zanesville Now, a quick run-through of the major types of ceramics produced in Ohio, leaving out some economically important but esthetically marginal commodities such as brick , sewer tile, and bathroom fixtures, and filled with gross generalizations and oversimplifications: redware, salt-glazed stoneware, yellow ware and Rockingham. Early Ohio Utility Ware Redware--In the beginning, say 1780, a crude, low fired pottery that burned to a red color and so known as “redware” was the standard material for utilitarian pottery, covered with a clear lead glaze to make the pots and plates water-proof. Redware is still made today, most obviously in the common unglazed flower pot. Unfortunately for the pioneers, the lead glaze proved to be poisonous, but by the time that was discovered redware was giving way, circa 1820, to a higher fired, sturdier stoneware, glazed with common rock salt. Ohio Redware Redware Crock H. T. Kellogg New London, Ohio ca. 1850 Ohio: Early Utility Ware OHIO SALT-GLAZED STONEWARE During pioneer days there was little impulse to decorate or even to put the potter’s name on redware. Stoneware more frequently bore the name of the manufacturer, usually impressed, and it was sometimes embellished with bright blue cobalt designs,or more rarely with incised sgraffito designs, primitive but decorative. D. Fisk Jug, Akron ca. 1850 Around 1840, a refined earthenware that burned to a yellow color and therefore was known as “yellow ware” became quite popular, in large part because unlike redware and stoneware it was not thrown” on the potter’s wheel but could be molded into a much greater variety of shapes. Yellow ware, often covered with a clear brown “Rockingham” glaze was so cheap Early Ohio Utility Ware Yellow Ware that manufacturers seldom bothered to mark with with their name, although much of it was virtually indistinguishable. As a case in point, this yellow ware chamberpot – about as utilitarian as one can get-- could have been made by any of several dozen different potteries, but excavation at the Quaker Valley pottery in Rogers, Ohio (near East Liverpool)recovered distinctive sherds that let us identify this particular example. Decorated Yellow Ware I digress a bit to show several rare examples of decorated Ohio yellow ware and stoneware. The only known piece of pottery from Salineville, Ohio’s Eureka Pottery, ca. 1877, in business for only a few years, possibly because it could not possibly afford to hand-paint all of its ware like this, probably because it could not compete with larger yellow ware factories in nearby East Liverpool, and also because yellow ware by this time was losing its popularity in favor of white ware. Diligent research in court house records and every other possible documentary source fails to determine where in Salineville this pottery stood. The sole historic reference to it is a directory entry that simply places it somewhere on Main Street. Eureka Pottery, Salineville ca. 1877 Quaker Valley Rebecca at the Well Rockingham Decorated Teapot The Quaker Valley Rebecca at the Well teapot is an fine example of Rockingham yellow ware. The Rebecca motif was very popular following the Civil War because of the woman’s social/religious/ self-improvement society, the Daughters of Rebecca. Over 45 variants of this design are know, although only about ten can be identified to manufacturer. Test excavation at the Quaker Valley Pottery had the serendipitous result of identifying distinctive sherds of this particular teapot style. Quaker Valley Rebecca Teapot ca. 1885 Sgraffito Decorated Stoneware Standard Pottery Co. I mentioned incised sgraffito decoration rarely occurring on some stoneware. Here is the only known example of stoneware pottery from Salineville’s little Standard Pottery Co. and a fine example of serendipity. Possibly the first piece of pottery made in the kiln, it has been inscribed STANDARD POTTERY CO. and a picture of a round beehive kiln and the tall chimney that carried the noxious fumes away. We might wonder whether the Standard Pottery actually looked like this—the site is now a car wash—but fortunately a contemporary “birdseye view of Salineville” just barely managed to include the kiln and chimney. And the layout corresponds well with existing Sanborn fire insurance maps. Sgraffito Decorated Stoneware Standard Pottery Albany Slip Jug Standard Pottery Salineville ca. 1900 Sgraffito Decorated Stoneware Riley Bratton Pottery One more example of sgraffito-decorated stoneware, from Riley Bratton’s small pottery in western Muskingum County. Twenty years ago this site was destroyed by amateur bottle collectors digging for relatively complete crocks. The did not find any whole pots or jugs but saved the decorated sherds on the theory that someday they might run across a complete example that could be identified by virtue of the decoration. The theory was a good one , but happily I was able to photograph the sherds and use them to identify this crock, as well as several others. In particular, the impressed numerical capacity marks include fine cross-hatching that perfectly matches that on the jug. The sad fact is that this is only one of several hundred similar stoneware pottery sites that have been destroyed by indiscriminate digging. Sgraffito Decorated Stoneware Riley Bratton Jug ca. 1850 Sherds from Riley Bratton Pottery Muskingum County, Ohio Later Ohio Utility ware Following the Civil War, yellow ware and Rockingham gave way to more popular white ironstone and finer semi-vitreous china or semiporcelain—not quite translucent or hard enough to be called true porcelain, but providing much more attractive table ware and toilet ware (wash pitchers, etc.) than did yellow ware. Both the heavy duty ironstone and lighter weight semi-porcelain provided excellent surfaces for first transfer printing and later decal decoration of colored designs—and this lead to the huge china dinnerware industry that provided tableware for most of us in our youth and childhood. It also lead to a large variety of advertising and commemorative china, as well as novelty pottery and later, innumerable ash trays and salt and pepper shakers. Later Ohio Utility Ware White Ironstone Vitreous Semi-Porcelain Brockmann Pottery Cincinnati Tea Leaf Ironstone ca. 1890 D. McNicol East Liverpool Star Players Plate ca. 1915 Ohio Art Pottery Finally we get to Art Pottery, almost entirely a child of the the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876, when a French Limoges technique of hand-painting glazed earthenware was introduced and became extremely popular in the United States, particularly in Cincinnati-- need I mention, the home of the Taft family? A wealthy young woman named Maria Longworth Nichols Storer organized a group of her friends into the Cincinnati Pottery Club, and this eventually lead to the Rookwood Pottery, probably the best know art pottery in the world. One of Mrs. Storer’s friends, Laura Fry, developed the atomizer technique for applying decoration, left Rookwood for a Steubenville pottery, and patented the process. At what point any friendship with Mrs. Storer ended is not known, but it had definitely chilled by the time Fry tried to enjoin the Rookwood Pottery from using her decorating technique. At this point, Judge William Howard Taft declared that Fry’s process was not a new one and anyone could use it to decorate pottery. Andy everyone did. Ohio Art Pottery Weller Pottery, Zanesville ca. 1915 Zanesville Art Pottery LaMoro Ware Marco Pottery 1946 Zanesville, Ohio Art China The dinner ware manufacturers were quick to sense a good thing and tried to compete by developing their own lines of ‘art china”—often just a designation for their fancier dinnerware. Art china proved popular for a number of years immediately before and after the turn of the last century but was not sufficient to be anything more than a sideline. It gradually devolved into the production of souvenir and commemorative ware, including give-aways and novelty items such as calendar plates and advertising novelties. Ohio Art China Laughlin Art China ca. 1905 East Liverpool, Ohio Harker Calendar Plate East Liverpool, Ohio 1907 Novelty Ware Chic and Grindley Pottery Zanesville and Sebring 1945 Juanita Ware Dalton Ohio ca. 1950 Cow Creamer Cordelia China Dalton Ohio 1948 Nicodemus Lion Columbus 1950 Ford Ceramic Arts ca. 1940 Columbus Four Calla Lily Vase from Four Different Ohio Potteries Art Pottery Archaeology So what does all this have to do with archaeology? or vice-versa? I will give one example of how our knowledge of archaeology can contribute to the understanding of an archaeological site, but frankly this does not happen often, because archaeologists understandably are not particularly interested in such recent sites. And art pottery, while it was not all especially expensive when it was made, is not often found even on 20th Century sites. Art Pottery Archaeology: Crabapple Creek Farmstead Farmhouse Foundations Pottery from Dump Here are the stone foundations of a small farmhouse in eastern Ohio, near Flushing, Belmont County, since strip mined away for coal. Before the coal company could begin mining, it had to demonstrate that no structures or sites eligible to the National Register of Historic Places would be impacted. One criterion used is whether the site is younger than 50 years (i.e., 1950), and this can sometimes be determined by examining the refuse dump associated with such farmhouses Crabapple Creek Farmstead In this case, along with numerous broken and complete canning jars, Clorox jars, milk bottles, etc., some fragments of pottery occurred, including the tail end of a blue swan planter made by the American Bisque pottery of Marietta, Ohio, ca. 1930-1980, a plain coffee cup identifiable as having been made by the Scio Pottery (1934-1982), only about 15 miles north of the farm site, and a broken art pottery vase marked Hull, with embossed water lily. Throughout the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, major “industrial” art potteries, including Roseville Pottery , of Zanesville, Ohio, and Hull Pottery of Crooksville, Ohio, produced a new floral line every year or so. In the case of Hull, which, incidentally, began as a manufacturer of standard stoneware crocks and jugs, their Waterlily line was made for only two years, 1948-1949, though its demise may have been due partly to the total destruction of the Hull Pottery by flood and fire in June, 1950. Archaeologically, the point is that, allowing a year or two for this Hull Water Lily vase to be broken and discarded, the farm dump clearly dates later than 1950. Hull Art China Hull Water Lily ca. 1948 Hull Pottery, Crooksville, ca. 1915 Art Pottery Archaeology: Considerations Of more interest to me is the ability to use archaeological concepts and techniques to determine new information about art pottery. This involves some obvious question such as: Where to dig? As mentioned in the case of the Eureka yellow ware pottery, some simply cannot be located precisely. More importantly, there should be a specific reason and rationale for excavation. Archaeologists don’t just dig randomly, they excavate in order to test hypotheses and obtain new knowledge. In some cases, Serendipity occurs and we find more than we are looking for or something entirely different than what we were looking for. But in almost all cases there are a number of constraints. and Constraints Constraints: • Permission of the land owner is essential. • There may be nothing significant to excavate—there may be no ware there. Perhaps the site has been completely removed or destroyed, by subsequent industrial activity or , as in the case of Riley Bratton’s stoneware pottery, by over-enthusiastic amateurs. • Any archaeological activity involves time and labor, which is to say money. There are few institutions sufficiently interested in the history of art pottery as to sponsor expensive excavations. • Art pottery archaeology can involve redundancy in two ways. Most pottery sites yield an incredible amount of ceramic material that is essentially the same. Thousands of sherds provide no additional data but must be excavated and processed, if not curated. Archaeological work on historic pottery sites may also be quickly made redundant or passé with the discovery of a previously unknown company catalog. Here, librarianship has proven useful, although newly discovered catalogs, regardless of condition, usually command prices comparable to the pottery they describe and consequently don’t end up in library collections . The few surviving trade catalogs are rapidly snapped up by art pottery collectors when they occasionally come on the market. J. B. Owens Catalog, Zanesville, Ohio. 1895 Archaeological Contributions Finally, I would like to present some examples of how archaeology can contribute to our knowledge of the history of art pottery. In the mid 1990s, a group of high school students from Rocky River, on Cleveland’s west side, decided to excavate at the nearby site of the Cowan Pottery, much of which is still standing. During the 1920s and early ‘30s, before succumbing to the Great Depression, Cowan was world famous for its art deco ceramics. Cowan was even asked to head OSU’s new ceramics department, but recommended Arthur E. Baggs instead. And Cowan artist Paul Bogatay taught at OSU for many years. Example 1: Cowan Pottery The Crew The Site While these students’ field technique was perhaps not the best, they did screen and they did find sherds of Cowan art pottery. Cowan Archaeology Cowan Dig Cowan Decanters From Bassett & Naumann 1997 You will note the bright red fragment matches the top of the Cowan “King of Hearts” decanter. And … Cowan Pottery there is a fragment of one of Cowan’s “Sunbonnet Girl” bookends. But as interesting as this endeavor was as a high school project, it did not contribute or discover any new knowledge about Cowan, for the simple reason that this pottery has been so thoroughly studied that there is not much left to discover. Example 2: Pope-Gosser Pottery or, Why Bother? Clarus Ware, Pope-Gosser Pottery, ca. 1905 Pope-Gosser Today Pope-Gosser Plant Pope-Gosser Waster Dump Similarly, Clarus Ware is a very nice Edwardian art china produced by the Pope Gosser Pottery of Coshocton, Ohio, for a few years around 1903. And one can got to Coshocton, where some of the Pope-Gosser buildings still stand—it produced good quality dinnerware until 1958, though not of the quality of their early Clarus Ware, which has been confused by experts with R.S. Prussia china. If you cross the railroad tracks and slide down the creek bank, you will find PopeGosser’s waster pile, tons of discarded broken dinnerware, mostly unglazed. But there is no reason to excavate here. Their Clarus Ware shapes as well as all of their dinner ware is not only well documented but commonly available. Here is an excellent example of redundancy: what could anyone possibly learn from all these sherds? Example 3: Florentine Pottery Ohio Centennial Vase and Look-alike With our third example we will have better luck. The Florentine Pottery was found in Chillicothe, Ohio, in 1900 by a wealthy furniture store owner who hired a potter away from the Owens Pottery of Zanesville. Although it was claimed that George Bradshaw accidentally discovered an unusual metallic glaze shortly before his death, it is so like Owen’s Feroza glaze that he undoubtedly had simply taken the Owens formula along with him. In any case, Florentine’s EFFECO glaze won a prize at the 1904 St. Louis World Fair. Florentine pottery was seldom if ever marked. The one tripodal vessel was made to commemorate the Ohio centennial in 1903 and is know to have been made by the company; the very similarly-shaped pot so closely resembles it that it can be comfortably attributed to the pottery as well. Florentine Pottery Effeco or Efpeco? Several years ago I found a matt green vase marked, unfortunately above the glaze, so that anyone might have written it, Florentine Pottery EFPECO ware 1903. Whoever wrote it knew what they were talking about, because a letter was eventually discovered in the Ohio Historical Society’s collection, in which the company mentions their EFPCO ware. “Effeco” was simply based upon a typographical error in the Brick and Clay Record, a weekly trade publication that OSU Libraries happens to have it in its collections. Florentine Pottery ca. 1905 Today But wouldn’t it be nice to confirm this identification by being able to go to Chillicothe and find some sherds of EFPECO ware? Here is a contemporary view of the Florentine Pottery and what it looks like today. The additional buildings were added after the Florentine Pottery turned from artware to sanitary ware in 1905. Fragments of bathroom sinks and toilet bowls are the most common sherds found at the site today. But if you look to the upper end of the pottery buildings in the postcard view, you will see mounds of white waster material along the railroad. Florentine Pottery • Sherds from site and matching jardiniere If we go there today and excavate a bit, we find both glazed and unglazed sherds of Florentine jardinières and pedestals and umbrella stand, the chief forms of artware that the pottery made during its brief existence. Haunting antique shops and auctions has produced matching examples of some of Florentine’s blended glaze ware, and before this research Florentine Pottery • Sherds and matching jardiniere & pedestal Much of this ware—this green and gold glazed jard and ped in particular—would have been ascribed to a Zanesville art pottery. This undoubtedly was another glaze formula that Bradshaw brought with him from Zanesville. From the Ceramic Sublime to the Ceramic Ridiculous We now move from the ceramic sublime to the ceramic ridiculuous—from art pottery to novelty pottery. This is a Sanborn fire insurance map of the U.S. Novelty Pottery (a.k.a Chic Pottery) along the west bank of the Muskingum River in South Zanesville, ca. 1950. This is one method of determining precisely where to excavate. Example 4: Chic Pottery, Zanesville For years the site has been dug through by local citizens intent on finding ceramic figurines and such that are relatively undamaged and can be sold in local shops. That effort has been only moderately successful and any archaeological integrity that this portion of the site may have had has been destroyed in the process. The digging has, however allowed me to collect examples of virtually every shape that the Chic Pottery produced, along with the actual plaster molds in which the pottery was formed. Since Chic Pottery is often unmarked and confused with the similar products of other local novelty potteries, this work is of some value. I have even been able to locate the daughter of the Hugh Garee, the artist who designed many of these molds. Chic Pottery Hound Dog Figurines and Treed Opossum Of more interest archaeologically is the fact that beneath the several feet of Chic pottery debris, at least in the small area of hillside exposed by the outlet of Goose Creek, there is a thin layer containing redware sherds undoubtedly produced by the Sam Weller pottery, which used this site for storage during the 1870s. Here you may be able to see a few redware sherds below about 4 feet of blast furnace slag used to stabilize the railroad spur, above which are light-colored sherds of Chic pottery. In terms of stratigraphy—the preservation of superimposed layers of different age—this is as good as it gets in archaeological terms. The sign, put up only recently does not say “No Trespassing,” it warns that during high water Goose Creek delivers raw sewage into the Muskingum. It is not a pleasant place to work under the driest of conditions. But these redware sherds can be used to identify Weller’s earliest pottery, which consisted mostly of decorated flowerpots and cuspidors. Chic Pottery, Zanesville Mouth of Goose Creek Chic Pottery Novelties A sample of Chic novelties speaks volumes and suggests why the pottery did not survive beyond 1955. There simply was not enough demand for novelty ashtrays, salt and pepper shakers and florists’ ware, despite fairly ingenious marketing, such as … Chic Pottery Novelties Aladdin Camel and Original Hugh Garee Model for it this camel figurine, one of which you can see on display in the Aladdin Temple on Stelzer Road. Shown with it is the original model, from which designer Hugh Garee made the plaster molds from which the ceramic figurines were made. Also a “Father Knickerbocker” shoe souvenir of the 1939 New York World’s Fair, though made for many years after. Father Knickerbocker Shoe 1939 Mold from Dump Example 5: Peters and Reed Pottery Standard Glaze Ware From M. & S. Sanford 2000 Briefly, back to art pottery. Some experts attribute this standard glaze ware with sprigged-on cameos, much like Wedgwood in concept though entirely different redware body, is attributed to the Peters and Reed Pottery of South Zanesville. Others note that identical shapes were used by the Samuel Weller Pottery and think that the line was made by Weller. No one has found any documentation, despite the fact that catalogs and other printed materials are available for both potteries. Peters and Reed Site Today Ground Surface At the Peters and Reed factory site, now a parking lot, the ground is littered with bits of redware flower pot and art pottery, and about ten years ago the O.K. Concrete Co. excavated two huge holes to dump their concrete mixer wastewater into. This uncovered mountains of Peters and Reed sherds, 90% of which were plain flower pots. I avidly collected the fancier sherds—just like the guys at the Riley Bratton pottery—and found most of the known Peters and Reed art pottery lines represented, but none of this standard glaze sprigware. I am fairly well convinced that it wasn’t made here. Owens/Brush Pottery Brush Pottery Building Waster Material Another art pottery historian believes that this ware was made by the J. B. Owens Pottery of Zanesville prior to its destruction by fire in 1905. The Brush Pottery, which took over the Owens site, burned in 1918, although the building is still used today by the Hartstone Pottery. Considerable pottery debris litters the surroundings, and we are attempting to get permission to test excavated for “Peters and Reed sherds.” Example 6: Roycroft Roycroft Bookstand Copper Bud Vase From D. Rago 2002 A final example of the potential of an archaeological approach to art pottery involves the famous Roycroft industry of East Aurora, New York, founded by Elbert Hubbard in 1895, best known for its furniture and copper arts and crafts objects. The copper bud vase, incidentally was designed by Dard Hunter, papermaker and artist from Chillicothe, Ohio We now know of another Roycroft Ohio connection. Following the death of Elbert and Mrs. Hubbard on the Lusitania in 1915, their son continued the Roycroft project but with dwindling success. Some money was raised by selling small souvenir jugs of honey—the honey bee, noted for its industry, was a sort of icon for the Roycrofters. Many Roycroft collectors assume these little brown jugs were made at East Aurora by the Roycrofters, but in fact they were bought wholesale from a previously unknown pottery that simply used the Roycroft insignia. Hold this thought while I shift to an unusual ceramic tradition common in the Southern United States, that of the grotesque effigy jug., a tradition that may be traced back to African slaves but in any case has seen an incredible renaissance during the last 15 years or so, to become a regular cottage industry in parts of South Carolina and Georgia. Example 6: Face Jugs A Variety of Contemporary Southern Face Jugs From Southern Folk Pottery Collectors Society 2001 Roycroft John Dollings Face Jug White Cottage ca. 1870 Ed Hicks Face Jug Star Pottery 1930 Ohio, too, had a small effigy jug tradition centering around the town of White Cottage, southwest of Zanesville. Here around 1870 John Dollings produced several effigy jugs These are very collectible and now sell for in excess of $10,000 each. The tradition continued as late as 1930 when Ed Hicks, working at the Star Stoneware pottery in Crooksville, Ohio, south of Roseville, made and signed and dated one distinctly like the earlier Dollings jugs. Roycroft Honey Jugs About 15 years ago, I saw but did not acquire a miniature effigy jug identical in style to Ed Hicks’ but bearing the impressed Roycroft logo, convincing me that the Roycroft honey jugs were made at the Star Pottery. Just two years ago I was able to acquire what I think is the same miniature jug and discovered that it, too, is dated 1930. Roycroft Roycroft Miniature Face Jug and Base So, I repeat myself, just as with Chillicothe’s Florentine Pottery, wouldn’t it be great to be able to go to the site of the Star pottery and find some Roycroft-marked sherds? Crooksville Star China Star Stoneware Co. Site Today Here is what the pottery looked like when it was in operation and what the site looks like today. Serendipitously, I visited the site while the footers for this new building were being excavated and found lots of Star Stoneware sherds, but no little brown jug fragments. Subsequently, however, a Crooksville pottery collector asked me about the Roycroft mark. He was unfamiliar with it but reported that his father had found broken sherds with the mark along the old Star Stoneware pottery railroad siding. Independent confirmation, I think, that Star Stoneware employees were unwitting Roycrofters. Find the Roycroft Jug in This Picture Star Stoneware Railroad Siding Today But… wouldn’t it be great to be able to go back to that railroad siding and find a Roycroft jug? This is what it looks like today and back in that brush the ground is littered with stoneware sherds waiting to be excavated. The Unanswered Question In conclusion, I hope I’ve demonstrated how useful archaeology can be in learning more about the history of Ohio art pottery. There is one question, however that archaeology cannot answer, in fact would not even consider appropriate. Only each of you can answer it, and I will leave you with that question: Would I Want This Pottery on My Mantle? KT&K Lotus Ware East Liverpool 1897 Meric Art Ware ca. 1930 Wellsville, Ohio Alfred E. Neuman Bust Nouvelle Pottery, Zanesville ca. 1950 References and Further Reading Bassett, Mark, and Victoria Naumann Cowan Pottery and the Cowan School. Atglen, Pa: Schiffer, 1997 Evans, Paul Art Pottery of the United States. New York: Feingold & Lewis, 1987 Murphy, James L. Quaker Valley Pottery’s Rebecca at the Well Teapot. Ohio Historical Decorative Arts Association Newsletter. 5(1): 3, 1996 Murphy, James L. Ford Ceramic Arts, Columbus, Ohio. Journal of the American Art Pottery Association. 14(2): 12-14, 1997 Murphy, James L. Art Pottery Archaeology: The Enduring Enigma of Peters and Reed. Journal of the American Art Pottery Association. 16(6): 8-14, 1999 Rago, David Craftsman Arts & Crafts Auction Weekend, September 21/22, 2002. Lambertville, NJ: Rago, 2002 Sanford, Martha and Steve Sanfords Guide to Peters and Reed. Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer 2000 Southern Folk Pottery Collectors Society Absentee Auction Sale Event 17. Bennett, NC: The Society, 2001