Date: 4 January, 2013 (Abdul Razak Ayazi, Permanent Representation- Afghanistan)

advertisement

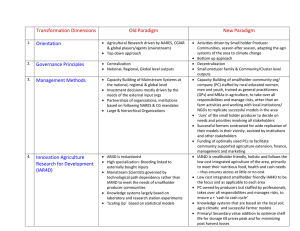

Date: 4 January, 2013 Comments on the Zero Draft of HLPE Study on Smallholder Investments (Abdul Razak Ayazi, Permanent Representation- Afghanistan) First I wish to make some general observations on the zero draft of the study and then address the three topics on which comments are requested by the HLPE Team, as well as reflecting on section 5 of the study (Recommendations). General Comments The study is wide-ranging and contains useful material on principal issues relevant to the investment needs of sustainable smallholder agriculture. The search conducted by the HLPE Team on this study is indeed extensive and praiseworthy. However, as a policy-oriented document the structure of the study needs improvements. In its present form, the text reads like an academic paper, which is obviously not the intention. The membership of CFS wish to be advised on key policy recommendations that are most suitable for improving the production and productivity of sustainable smallholder agriculture for different ecological systems. With this purpose in mind, the balance between broader and circumstantial issues and those germane to the development of sustainable smallholder agriculture needs a fresh look, with the aim of increasing the weight of the latter in the study. The section on Conclusions (which has not yet been written) should come before section 5 and should focus on substantive issues, thereby leading the way to a few key recommendations. Section 5 (Recommendation) should be made shorter and more focused. The essence of each of the 9 recommendations proposed needs to be expressed in a straight forward manner and in simple language, so the reader would know exactly what each recommendation entails. The Three topics 1. Definition and significance of smallholder agriculture: is the approach in the report adequate? For a policy-oriented study, the definition of “smallholder agriculture”, which also includes small fishers and indigenous forest dwellers, should be crisp and concise. 1 The three paragraphs of sub-section 1.1, when taken together, reflect a definition that is somewhat diffused. Recognizing that the definition of smallholder varies from region to region, from country to country and from location to location within a country, the symptoms are nevertheless commonly shared. On the global scale, smallholders, who practice intensive and diversified agriculture, are large in numbers, asset- poor, prone to exploitation, least beneficiaries of public services, most vulnerable to shocks, facing a wide range of socio-economic and technical constraints and struggling to survive in a global economy from which they hardly benefit. Given the policy nature of the study, sub-section 1.2 (How small is small) can be shortened and perhaps limited to the salient features of Figure 2 and Figure 3. This reduction will in no way diminish the importance of the valuable conclusion shown in bold letters on page 22 of the study. To provide a geographically balanced oversight on policy for smallholder agriculture, it may be advisable to also include in sub-section 1.3.2 (Policy concerns) one or two initiatives taken from Asia and the Pacific Region, where 87% of the world’s smallholder farmers live. Similarly, an example from Latin America and the Caribbean would be most appropriate because in that continent the profile of smallholder is different than in the land-scare continent of Asia. Sub-section 1.4, which represents historical trends in the average size per holding for 3 countries (India, France and Brazil), may not be that representative of the global picture. It would be advisable to show a single chart based on the last three or four censuses showing the evolution in the size of holdings for at least 10 small, medium and large countries in different regions and then attempt to make some comparisons, if feasible. Consideration could also be given to placing sub-section 2.5 after subsection 1.4 because the two sections are to a large extent complementary. The significance of smallholder agriculture is fairly well substantiated in Section 2. That said, it may be advisable to also mention milling in sub-section 2.1.2 due to its importance in rural areas and open a new sub-section on the contribution of smallholder agriculture to rural employment, as this aspect is highly significant and needs a separate treatment. In Box 4 on pages 34-35, mention should also be made to the third category of family farms that hire some labour on permanent basis. While this category accounts for only 6% of the 15 million family farms in LAC, it cultivates 25% of the most productive land of the 400 million hectares of family farms. 2 2. Framework for smallholder agriculture and related investments: is the typology useful, adequate and accessible for the problem at hand? Section 3 should present the investment framework most appropriate to smallholder agriculture. The existing text is not well focused on this issue and what is presented is somewhat academic. Generally speaking, the five types of capital/assets listed on pages 37-38 (Human, Social, Natural, Physical, Financial) equally applies to medium and large size holdings, though the mixture may differ between the three types of landholdings according to their specific characteristics and requirements. For investment in smallholder agriculture, three ways of asset creation are crucial, namely: (i) family labour for on-farm development (basically soil improvement; better use of family labour in improving animal productivity through crop/livestock integration; creation of home-based gardens; on-farm improvements that would increase water efficiency for crops, trees and livestock; and preservation of genetic resources); (ii) community labour used in creating physical and human assets beneficial to smallholders as a group (erosion control, terracing, drainage, water harvesting, improved range management, construction of community owned wells, storage, on-farm roads, centres for cooperative and farmer organization, facilities to enable the group employment of women and the development of skills for young boys and girls); (iii) Public goods that gives an upward shift to the technological frontier most suitable for smallholder (roads connecting smallholders to nearby markets, small and medium irrigation schemes, electricity, public education, sanitation, health services, affordable financial services and communication, more or less on the model practiced in China and some other developing countries). Public-private partnership in research and extension and building on traditional knowledge are also considered as important public goods. Corporate investment has a role to play in the development of smallholder agriculture, provided the benefit sharing arrangements are carefully worked out for the benefit of both parties, a subject matter that presumably will be addressed in the study on rai. 3 3. Constraints on smallholder investment: are all main constraints presented in the draft? Have important constraints been omitted? Generally speaking, section 4 (A Framework for Smallholder Agriculture and Investment) contains relevant conceptual material. However, the section attempts to simultaneously cover context, constraints and potential solutions in mitigating the negative impact of the constraints on production by smallholders and improving household income. It may be advisable to keep the focus of section 4 on constraints to investment and their typology and placing context and potential solutions to other sections of the study. Nevertheless, the good features of section 4 are: Underscoring the complete absence or severe limitation of legal protection for smallholders and their political and economic underweight within their respective social environments. The writings of Mr. Olivier de Schutter, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, could be used to substantiate legal protection for smallholders; A very good assessment of the three types of risks facing smallholder agriculture and their interaction (sub-section 4.3); A good exposé of the policy disincentives (sub-section 4.4); An excellent presentation of typology of smallholder according to the interplay of 3 essential factors: assets, markets and institution, especially Box 9 on page 54. The assessment is comprehensive, issue-oriented and with focus on policy issues. I cannot think of any important thing to add. Section 5 ( Recommendations) Section 5 is too lengthy and the recommendations are somewhat lost within the expansive text. For example, what exactly is being recommended under 5.2.1? Is it that smallholder should have full access to all public services as listed in lines 4-9 of the first paragraph on page 58? If so, it needs to be concise and precise. That said, the 9 recommendations (4 addressing the constraints facing smallholders, 3 focusing on specific priority domains and 2 related to implementation strategy) are undoubtedly pertinent and strategic in nature. Avoiding a plethora of recommendations is also commendable. The question is the presentation of the recommendations in short and unambiguous language. It would be very helpful if each of the 9 recommendation can be supplemented with one or two country-based experience, like Box 10 on yields, page 59, and Box 11 on Rabobank, page 51. 4 5