Argument: Purpose and Process

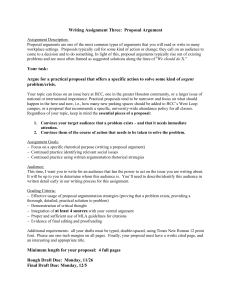

advertisement

THE WRITING CENTER Argument: Purpose and Process Written arguments likely appear in your everyday life, whether you read them, for example, in the form of an editorial in a newspaper, or write them, as in the form of a cover letter to a potential employer, asking to be hired. Arguments can also be visual: advertisements are a prime example. Using reason and emotion to persuade others is a daily part of every person’s life—private and public—and producing effective arguments is a vital skill in and out of school. PURPOSE Persuasion: An attempt to influence the audience towards a particular action or belief. o Examples advertisements to induce one into buying a particular product or brand campaign letters to induce one into donating money to a certain candidate application letter to gain admittance to a university or organization Justification: An attempt to rationalize to yourself and others what you believe and why. o Examples address to constituents by a public figure regarding an issue like taxation letter to board members by a CEO that defends how profits are spent job evaluation delivered to an employee by a supervisor Problem Solving and Decision Making: An attempt to find solutions to an issue under debate. o Examples legal briefs presented to a judicial member who is rendering a decision business memos sent to decision-makers in a company proposals created by contractors who have to satisfy their clients and regulators D:\98927888.doc Created on 8/5/2010 4:21:00 PM: Contributor: Teri Green Material adapted from Prentice Hall Reference Guide 6th Edition by Muriel Harris THE WRITING CENTER Argument: Purpose and Process Successful argumentation asks you to conduct research, which is just a fancy way of saying ‘finding information,’ in order to locate support for your claims. In addition, you must also engage in a process of reasoning so that you can both explain and defend your actions, beliefs, and ideas. Once you’ve conducted your research and begun your reasoning process, you will also need to take into account such factors as credibility of material and yourself as the author, audience response to you, and later, the development of your material and how you organize it in a persuasive, sound manner. PROCESS Topic Selection: The topic should be one that is debatable or several possible solutions. Additionally, the topic should be relevant to your audience’s concerns and of interest to them. Writer’s Credibility: Your motives for argument should be apparent to the audience as reasonable and worthwhile, and ideally should be a way to establish some common ground. Also, avoid ambiguity and exaggerated statements, which only weaken your credibility. Audience: To whom are you writing? If the audience agrees with you already, then what is the purpose of making your argument? If they do not agree, can you acknowledge and address their viewpoints? Research: to gain the reader’s trust and respect, you must indicate you are in possession of credible information, are truthful, and are reasonable in your consideration of opposing points. To accomplish this, you must look for and gather information that is credible and relevant to your argument, including information that may be contradictory, in order to address any concerns about your credibility as the author of the argument. Outline: several patterns of argumentation exist that can help you to organize your material into a cohesive, logical, and well-supported argument. These patterns are available in any book on research writing, grammar reference books, books on rhetoric and argumentation, and in simplified version as a handout from the University of Toledo Writing Center. D:\98927888.doc Created on 8/5/2010 4:21:00 PM: Contributor: Teri Green Material adapted from Prentice Hall Reference Guide 6th Edition by Muriel Harris