Chapter 2 Phonetics

advertisement

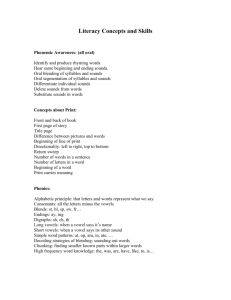

Chapter 2 Phonetics Phonetics: the study of the speech sounds that occur in all human languages to represent meanings I. Sound Segment A. Speech utterances can be segmented into individual units. B. According to an ancient Hindu myth, Indra may be the first phonetician. C. We do not pause between words even though we sometimes have that illusion. Example 1: The two-year-old child of one of the authors of this book says the sentence “I’m holding on” as “I’m holding down”. Example 2: “A napron” became “an apron”. D. If you have a language you have no difficulty segmenting the continuous sounds. II. Identity of Speech Sounds A. Our linguistic knowledge our mental grammar, makes it possible to ignore nonlinguistic differences in speech. We are capable of making many sounds that intuitively we know are no speech sounds in our language. Example: The clicking sounds like “tsk” are not part of English sound system, but they are speech sounds of the languages spoken in the southern Africa. B. The process by which we use our linguistic knowledge to produce a meaningful utterance is a very complicated one. C. 1.Acoustic phonetics: the study of the physical properties sound themselves 2.Auditory phonetics: the study of the way listeners perceive the speech sounds 3.Articulatory phonetics: the study of how the vocal tract produces the sounds of language III. Spelling and Speech A. The sounds in a language often are represented by spelling rather unsystematically. B. The Phonetic Alphabet The discrepancy between spelling and sounds gave rise to a movement of “spelling reformers” called orthoepists. They wanted revise the alphabet so that one letter would correspond to one sound and one sound to one letter. C. The efforts and contribution of George Bernard Shaw to the phonetic alphabet. D. In 1888 the interest in the scientific description of speech sounds led the International Phonetic Association (IPA) to develop a phonetic alphabet to symbolize the sounds found in all languages. E. A phonetic alphabet should include enough symbols to represent “crucial” linguistic differences. At the same time it should not, and cannot, include noncrucial differences. Articulatory Phonetics I. Airstream Mechanisms A.pulmonic sounds: speech sounds are produced by pushing lung are out of the body through the mouth and sometimes through the nose. Lung air is used. B. egressive sounds: the air is pushed out. C. implosives sounds: the air is sucked in instead of flowing out; produced by a glottalic airstream mechanism. ( occur in the languages of the American Indians and throughout Africa, India, and Pakistan.) D. clicks sounds: the air is sucked in; produced by a velaric airstream mechanism.( occur in the Southern Babtu languages.) E. ejectives sounds: the air in the mouth is pushed out produced by a glottalic airstream mechanism. ( found in many American Indian as well as African and Caucasian languages.) II. Voiced and Voiceless Sounds A. B. voiceless: the vocal cords are apart, the airstream is not obstructee at the glottis and it passes freely into the supraglottal cavities. voiced: the vocal cords are together, the airstream forces its way through and causes them to vibrate. C. The voiced/voiceless distinction is a very important one in English. It is this phonetic feature or property that distinguishes between word pairs: rope/robe fate/fade rack/rag III. Nasal and Oral Sounds A. oral sounds: the velum is raised all the way to touch the back of the throat the passage through the nose is cut off; the nasal passage is blocked in this way, the air can escape only through the mouth. B. nasal sounds: the velum is lowered, air escapes through the nose as well as the mouth C. The phonetic features or properties permit the classification of all speech sounds into four classes: voiced, voiceless, nasal, oral. One sound may belong to more than one class. IV. A. Places of Articulation Labials 1. bilabials: [p], [b],[m] are articulated by bringing both lips together. 2. labiodental: [f],[v] are articulated by touching the bottom lip to the upper teeth. B. Interdentals: the th in the words thin and then, the tip of the tongue is inserted between the upper and lower teeth. C. Alveolars: to articulate a [d], [n], [t], [s],or [z], the tongue is aised to the bony tooth ridge; [t] and [s] are voiceless alveolar sounds, [d] and [z] are voiced, D. Velars: produced by raising the back of the tongue to the soft palate or velum, as the initial and final sounds of the words kick, gig, and the final sounds of the words back, bag, and bang. E. Palatals: the front part of the tongue is raised to a point on the hard palate just behind the alveolar ridge, as the voiceless patatal sound begins the words shoe, sure and ends the words rush, push. F. Coronals: the alveolar and palatal sounds are grouped together as coronal, sharing the common property of being articulated by raising the tongue blade toward the hard palate. Manners of Articulation The voiced/voiceless and oral/nasal features do not refer to the movement or position of the tongue, teeth, or lips. Rather they reflect the way the airstream is affected as it travels from the lungs up and out of the mouth and nose. Such features or phonetic properties have traditionally been referred to as manners of articulation or simply manner features. I. Stops and Continuants Sounds that are stopped completely in the oral cavity for a brief period are called stops, and the stream of air continues without complete interruption through the mouth opening are called continuants. [p],[b],[m]--are bilabial stops, with the airstream stopped at the mouth by the complete closure of the lips. [t],[d],[n]—are alveolar stops; the airstream is stopped by the tongue making a complete closure at the alveolar ridge [k],[g],[]--are velar stops with the complete closure at the velum. II. Aspirated and Unaspirated Sounds In English when we pronounce the word pit, there is a brief period of voicelessness immediately after the [p] sound is released. That is, after the lips come apart the vocal cords remain open for a very short time. Such sounds are called aspirated because an extra puff of air is produced. When we pronounce the [p] in spit, however, the vocal cords start vibrating as soon as the lips are opened. Such sounds are called unaspirated. Aspirated sounds are indicated by following the phonetic symbol with a raised H as in the following examples: pate [ph et] spate [spet] tale [th el] stale [stel] kale [kh el] scal [skel] III. Fricatives If you put your hand in front of your mouth and produce an [s],[z],[f],[v],[],[],[š],or[ž]sound, you will feel the air coming out of your mouth. The passage in the mouth through which the air must pass is very narrow, causing friction. Such sounds are called fricatives. [f] [v] --labiodental fricatives [s] [z] --alveolar fricatives [š] [ž] --palatal fricatives [] [] -- interdental fricatives IV. Affricates Some sounds are produced by a stop closure followed immediately by a slow release of the closure characteristic of a fricative. These sounds are called affricates. [tš] =[t]=[š] [dž]=[d]=[ž] V. Liquids In the production of the sounds [l] and [r], there is some obstruction of the airstream in the mouth, but not enough to cause any real constriction or friction. These sounds are called liquids. [l] is a lateral liquid, the tongue is raised to the alveolar ridge, but the sides of the tongue are down permitting the air to escape laterally over the sides of the tongue. [r] is produced in a variety of ways. Many English speakers produce [r] by curling the tip of the tongue back behind the alveolar ridge. Such sounds are called retroflex sounds. VI. Glides In articulating [j] or [w], the tongue moves rapidly in gliding fashion either toward or away from a neighboring vowel, hence the term glide. [j]-- palatal glide [w]--labio-velar glide [h]-- glide, somtimes classified as a voiceless glottal fricative. VOWELS When we pronounce vowels our oral cavities are open without any contact points and the airstream flows out freely. As for the quality of vowels, it’s determined by our tongues raised or lowered and our lips spread or pursed. Vowels aren’t like consonants.--they carry pitch and loudness and can be pronounced alone. In addition, for many of the beginning students, it’s more difficult to distinguish their articulatory features from each other by many different schemes. Because vowels are produced without any articulators touching or even coming close together. The writer said “ Only when you watch an x-ray movie of someone’s talking you’ll find why vowels have traditionally been classified.” According to what he watched in such a movie, he put three questions: 1. How high is the tongue? 2. What part of the tongue is involved; that is , what part is raised or lowered? 3. What is the position of the lips? And then he discussed the distinguishing features and others, such as diphthongs and nasalization below. (I) Tongue positions We can exam how vowels are produced with some parts of the relative not absolute. front (Height) High Back Rounded /u/ (boot) (beet)/i/ (bit)// /U/ (put) (bait)/e/ /o/ (boat) (Rosa) // (butt) // (bet) // Low (bat)/æ/ // (bore) // (bah) Front vowels /i/ a high front vowel /I/ a lower-high front vowel /e/ a higher-mid front vowel Back vowels /u/ a high back vowel /U/ a lower-high back vowel /o/ a higher-mid back vowel // a lower-mid front vowel // a lower-mid back vowel /æ/ a low front vowel // a low back vowel Schwa vowels // a unstressed mid-central vowel // a stressed mid-central vowel (II) Lip rounding All the back English vowels are pronounced with the lips rounded or pursed except //. On the contrary, non-back vowels are unrounded. However, it’s not true of all languages. French and Swedish languages have front- and back-rounded vowels. Mandarin, Japanese and the Cameroonian languages have high back unrounded vowels. EX. 中文一字[四]的發音含有類似英文 boot 的母音但唇形卻是non-rounded spread lips;而[速]則是high back-rounded lips. (III) Diphthongs They are described as a sequence of two sounds—vowel + glide. EX. bite aj a vowel + j glide rye bout aw a vowel + w glide brow boy j vowel + j glide soil (VI) Nasalization Of Vowels In English, nasal vowels occur before or after nasal consonants. (eg.Hint hint, bean bin, camp kmp, bone brn ) However, the languages like Southern Min, nasalized vowels may occur when no nasal consonant is adjacent. EX: pi ” compare ” pĩ ” not round ” PROSODIC SUPRASEGMENTAL FEATURES Such features as length, pitch, and the complex feature stress and how they are used in various languages to distinguish the meaning of words and sentences are often referred as prosodic or suprasegmental features. 1. Long vowels in English are produced with greater tension of the tongue muscles than their short counterparts and therefore also referred to as tense vowels. 2. In some languages there are vowels and /or consonants that differ phonetically from each other only by duration , Therefore, it is customary to transcribe this difference either by doubling the symbol or by the use of a diacritic “ colon” after the segment, as for example [aa] or [a:]. [bb] or [b:]/ 3. What are tone languages ? Give one example. Languages that use the pitch of individual vowels or syllables to contrast meanings of words are called tone languages. Take one word in Nupe (a language spoke in Nigeria) for example. [naa] [‵] L low tone “ a nickname “ [naa] [ - ] M mid tone “ rice paddy “ [naa] [′] H high tone “ young maternal uncle or aunt “ [naa] [ ^ ] HL falling tone “ face ” [naa] [ ] LH rising tone “ thick ” 4. What is contour tones ? And register tones ? Which tone of the language belongs to the contour tones ? Tones that “ glide “ are called contour tones; tones that do not are called level or register tones. The contour tones of Thai are represented by using for a falling tone a high tone followed by a low tone, and a rising tone is a low followed by a high. NOTE : In a tone language it is not the absolute pitch of the syllables that is important but the relations among the pitches of different syllables. 5. What are downdrift languages ? The lowering of the pitch is called downdrift.Many tone languages in Africa are downdrift languages.—high tone is lower in pitch than the preceding similarly marked tone. Therefore, whether the tone is “ high “ or “ low “ in relation to the other pitches, but not the specific pitch of that tone. 6. Let’s read the following sentence in Twi, we’ll find the relative pitch, rather than the absolute pitch, important. “ Kofi searches for a little food for his friend’s child. “ h LH L ádu h H H L á k L HL LHL m L H 7 6 h á 5 4 3 k á h du 2 1 7. m Languages that are not tone languages, such as English, are called intonation languages. DIACRITICS Diacritic marks on vowel nasalization, prosodic features, and tone can be used to modify the basic phonetic symbols. ( see p.207 - at the upper part of the page ) Phonetics is the science of speech sounds. It aims to provide the set of features or properties that can be used to describe and distinguish all the sounds used in human. The discrepancy between spelling and sounds in English and other languages motivated the development of phonetic alphabets in which one letter corresponds to one sound The major phonetic alphabet in use is that of the International Phonetic Association (IPA). All human speech sounds fall into classes according to their phonetic properties of features. During the production of voiced sounds the vocal cords are together and vibrating whereas in voiceless sounds the vocal cords or glottis is open and non-vibrating. Voiceless sounds may also be aspirated or unaspirated. Classes of sounds which differ according to their manner of articulation also include oral and nasal sounds, continuants or stops. Non-sonorant continuants are fricatives; the class of sonorant continuants include, vowels, glides, and liquids. Vowels form the nucleus of syllables and are therefore syllabic. They differ according to the position of the tongue and lips: high, mid, or low tongue; front or back of the tongue; rounded or unrounded lips. Length pitch and loudness are prosodic or suprasegmental features which also differentiate sounds. The vowels in English may be long or short, stressed or untressed. In many languages the pitch of the vowel or syllable is linguistically significant in distinguishing the meaning of words. Such language are called tone languages as opposed to intonation languages in which pitch is never used to contrast words. Diacritics to specify such properties as nasalization, length, voicelessness, syllabicity, stress, tone, or rounding may be combined with the phonetic symbols for more detailed phonetic transcriptions.