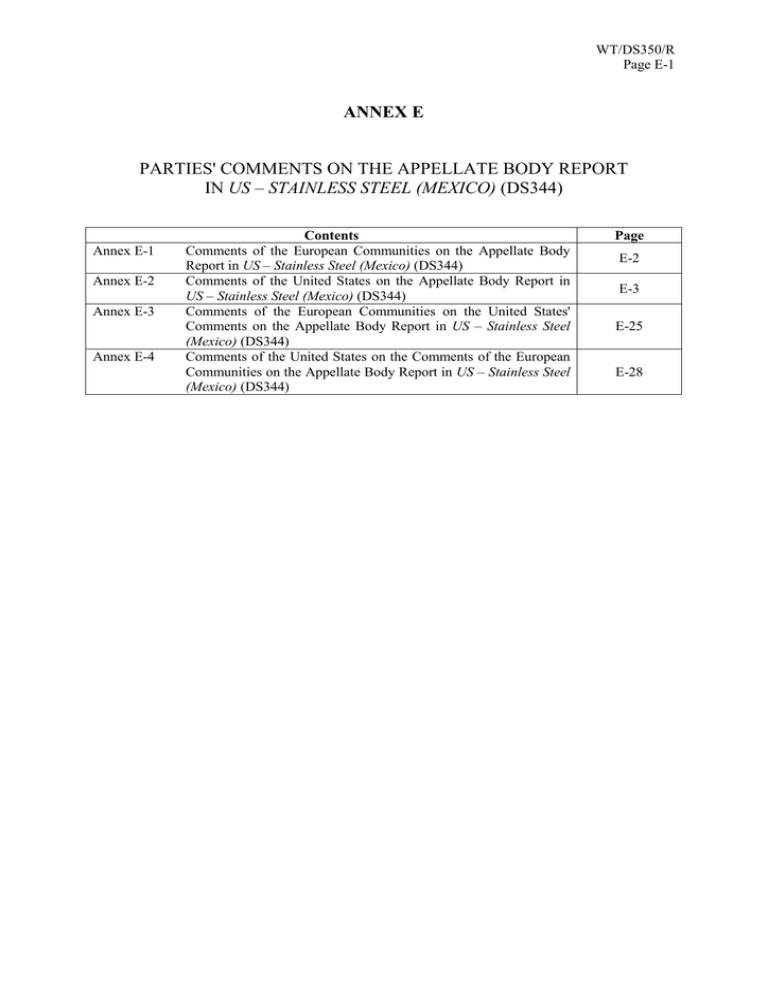

ANNEX E PARTIES' COMMENTS ON THE APPELLATE BODY REPORT

advertisement