ANNEX D FIRST AND SECOND MEETINGS OF THE PANEL

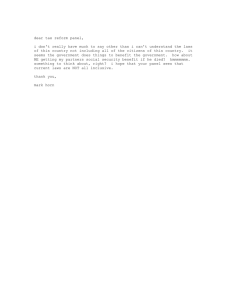

advertisement