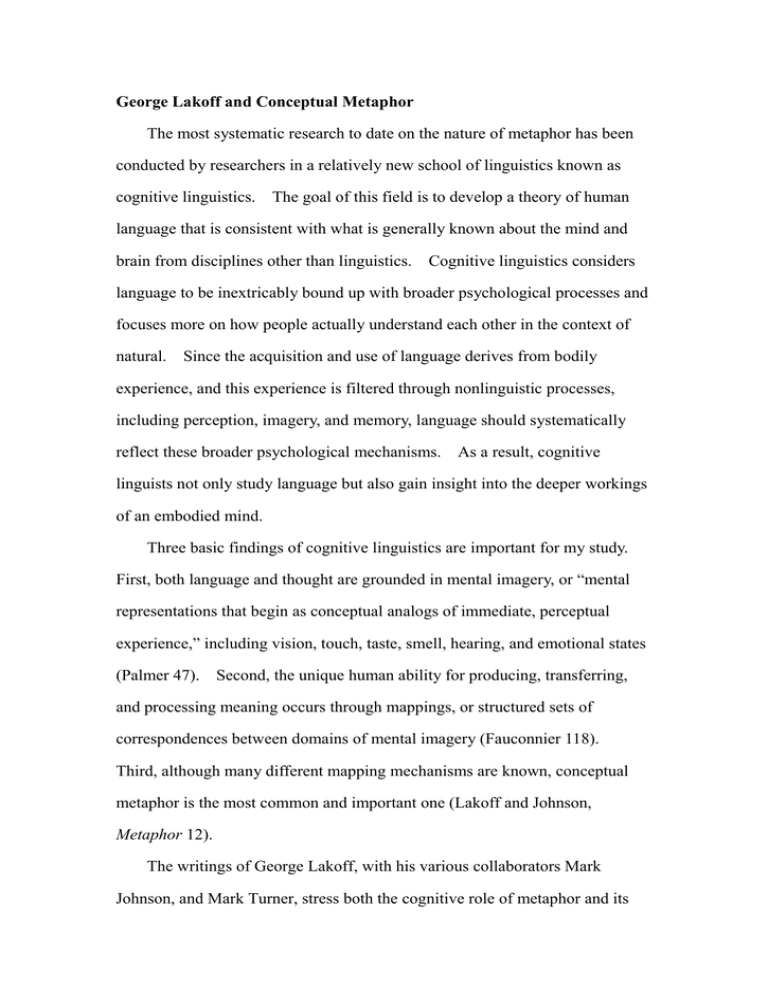

George Lakoff and Conceptual Metaphor

advertisement

George Lakoff and Conceptual Metaphor The most systematic research to date on the nature of metaphor has been conducted by researchers in a relatively new school of linguistics known as cognitive linguistics. The goal of this field is to develop a theory of human language that is consistent with what is generally known about the mind and brain from disciplines other than linguistics. Cognitive linguistics considers language to be inextricably bound up with broader psychological processes and focuses more on how people actually understand each other in the context of natural. Since the acquisition and use of language derives from bodily experience, and this experience is filtered through nonlinguistic processes, including perception, imagery, and memory, language should systematically reflect these broader psychological mechanisms. As a result, cognitive linguists not only study language but also gain insight into the deeper workings of an embodied mind. Three basic findings of cognitive linguistics are important for my study. First, both language and thought are grounded in mental imagery, or “mental representations that begin as conceptual analogs of immediate, perceptual experience,” including vision, touch, taste, smell, hearing, and emotional states (Palmer 47). Second, the unique human ability for producing, transferring, and processing meaning occurs through mappings, or structured sets of correspondences between domains of mental imagery (Fauconnier 118). Third, although many different mapping mechanisms are known, conceptual metaphor is the most common and important one (Lakoff and Johnson, Metaphor 12). The writings of George Lakoff, with his various collaborators Mark Johnson, and Mark Turner, stress both the cognitive role of metaphor and its roots in the human conceptual architecture. His experientialism places the human act of cognition in the center and proposes that cognition is vitally dependent on metaphor. Metaphor, as he defines it, is a mapping of conceptual structures from one domain onto another.1 Lakoff’s writings call for a reification of the status of metaphor, from a superficial rhetorical device that decorates our speech, to the status of a deep, cognitively-realized agency that organizes our thoughts, shapes our judgments, and structures our language. Metaphor is shown to pervade, or even saturate our everyday, non-rhetorical language to such a degree that a deviant view of the trope would leave little, or no scope for orthodoxy. Lakoff’s central thesis is that metaphors facilitate thought by providing an experiential framework in which newly acquired, abstract concepts may be accommodated. The network of metaphors that underlie thought in this way form a cognitive map, a web of concepts organized in terms which serve to ground abstract concepts in the cognitive agent’s physical experiences, and in the agent’s relation to the external world. A major component of the human cognitive map is what Lakoff and Turner call a cognitive topology, essentially “a mechanism by which we impose structure on space, in a way to give rise to spatial inferences” (47). The cognitive agent is itself an essential player in this organization—abstract thoughts are not structured in terms of objective 1 Lakeoff questions both the validity and primacy of a syntactic deep structure in formal models of language, in an effort to overturn the Chomskyan view that semantics emerges from an interpretative reading of syntax. Lakoff takes the new generative position that a deep semantic structure is posited at the core of language comprehension, effectively merging deep syntactic and semantic structures into a unified whole. This reversal is of little empirical consequence. to those who consider the central concern of linguistics to be the study of abstract language competence, rather than actual performance. However, the generative position does clear the way for a new view of metaphor in linguistics. Meaning is no longer subservient to syntax, nor is metaphor considered a superficial phenomenon of language as it was. spatio-physical properties of the world, but subjective, egocentric properties that the agent projects onto the world via his cognitive map. In Metaphors We Live By, Lakoff and Johnson develop a theory of experiential cognition that approaches what meaning is to the human. In contrast to the traditional objectivist view of cognition that sees it as the algorithmic manipulation of abstract symbols capable of providing internal representations of an external reality, their experientialism sees cognitive activity as motivated and constrained by our experiences in the world. In particular, Lakoff argues that we have an innate capacity to shape such experience and make it possible. As a principle, Lakoff opposes what he calls “objectivism,” which holds that thought is the mechanical manipulation of abstract symbols and that the mind is an abstract machine manipulating symbols essentially in the way a computer does. In this case, symbols get their meaning via correspondences to things in the external world, and thought is therefore abstract, disembodied, atomistic, and logical in the narrow technical sense (Lakoff, Women 12-13). He holds that thought is both embodied and imaginative, embodied in that the structures used to put together our conceptual systems grow out of bodily experience, imaginative in that those concepts that are not directly grounded in experience employ metaphor, metonymy, and mental imagery. Moreover, thought has gestalt properties and concepts have an overall structure that goes beyond merely putting together conceptual “building blocks” by general rules. In this case, thought is more than just the mechanical manipulation of abstract symbols (Lakoff, Women 14-15). In terms of experientialism, rational thought is the application of the imaginative processes and basic cognitive processes to the basic concepts and image schemas that we possess. Meaningful structures arise from the structured nature of bodily and social experience and our innate capacity to imaginatively project from the bodily, social or other interactional experiences to abstract conceptual structures. He thinks that we share a common experience and culture and possess a number of concepts, or categories that are recognized as “basic level.” Basic-level categories are formed at a level of abstraction “at which humans interact with their world most effectively” (Lakoff and Turner 133). In addition to basic-level concepts, we possess fundamental notions of spatial organization called image schemas. Image schemas are again embedded in, and structure, our direct experience of the world. However, they are more general than basic-level categories. They are common experienced relationships that pertain to humans and their existence in, and movement through, space. Image schemas are abstract patterns in our experience and understanding that are central to meaning and to the inferences we make. Image schemas also have a major role in producing categories. To recognize several elements as structured by the same image schema is to recognize a category. In addition, Lakoff identifies imaginative processes or imaginative projections, which act on the basic level concepts and image schemas and allow us to form abstract conceptual models. There are basically four imaginative processes: schematization, metaphor, metonymy, and categorization. It is important to distinguish concepts such as metonymy and metaphor as used in experientialism from their linguistic use. In experientialism, these, along with schematization and categorization, are fundamental to cognition. Thinking and reasoning involve applying the imaginative processes: linking and transforming the basic-level categories and image schemas into abstract concepts. The main process that we will be using is metaphor. Rather than simply a linguistic expression, metaphor is central to our thinking processes, a cross-domain mapping that conceptualizes one domain in terms of another. Lakoff’s experientialism relies heavily on mental spaces as a medium in which cognitive activities can take place. The concept of mental space refers to the partial cognitive structures that emerge when we think and talk. It is in these mental spaces that domains are defined, altered and merged. Cognitive models created through imaginative processes structure those spaces, and we think by connecting different mental spaces. We may have a space that structures our experienced reality, the other that structures future situations, and still another that structures fictional situations. There may be a lot of them and they are all connected. A metaphor connects two different mental spaces. When a connection is established between more than two spaces, it is termed a blend. Blending—integrating partial structures from different domains— is another special case of imaginative projection. Blending receives a partial structure from two or more input spaces, producing a new space that has emergent structure of its own. As shown above, Lakoff’s careful analysis of large numbers of conventional metaphorical expressions poses an experientialist position and reveals several general properties of conceptual metaphor. These properties will be reviewed with clearer accounts and examples, in an effort to offer a clearer picture about how metaphor and space are related. The properties reviewed in the following refer to metaphor as a cognitive process involving mental imagery, which is nonlinguistic in nature and thus can be compared to Lefebvre’s concept of metaphorization and metonymization. First, conceptual metaphors enforce a cognitive mapping. Conceptual metaphors project the cognitive map of a source domain onto a target domain. The target domain becomes grounded in the spatio-physical experience of the source domain.2 As a result, the schemas that mediate between conceptual and sensory levels in the source domain become active also in the target domain (Lakoff and Turner 133). In this sense, a metaphoric schema is a mental representation that grounds the conceptual structure of an abstract domain in the sensory and sensible basis of another domain, which is spatial and often more physical. Numerous everyday expressions in English, as Lakoff and Johnson point out in their Metaphors We Live By, can offer a clear picture of what conceptual metaphor is, especially in the terminology of journeys that talk about life experiences. These are surface expressions with an underlying, nonlinguistic metaphorical conceptualization that can be briefly described by the familiar idiom—”LIFE IS A JOURNEY.”3 People do not normally notice that they are expressing a metaphorical thought when they say things like “my career has come a long ways,” “I’m stuck in a terrible situation,” or “I’m now headed in a new direction.” The same holds true in such vague expressions as “I’ve got to move forward,” “I’ve gotta go through it,” “I’m finally getting where I want to be,” etc. Yet, English speakers immediately understand the meaning of such statements because they have internalized the metaphorical concept “LIFE IS A JOURNEY,” and use it to conceptualize life experiences and communicate about Lakoff’s notion of metaphor as a mapping from one cognitive domain to another as “one of the great imaginative triumphs of the human mind” has been echoed by the British paleo-anthropologist Steven J. Mithen in his The Prehistory of the Mind: The Cognitive Origins of Art, Religion and Science. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996). 2 This is Lakoff’s format of showing an analogy as a conceptual metaphor, which will be followed when conceptual metaphors appear in this study. 3 them using metaphorical expressions. The source domain in this metaphor is a journey, which suggests a starting point, obstacles to overcome, and a destination; while the target domain is life, which represents things that are difficult to conceptualize directly from bodily experience of the lived space. The conceptual structure of source domain is mapped onto the target domain: the perceivable properties and relations of the target domain correspond, point for point, with properties of the source domain. Second, conceptual metaphors are spatial and directional. The cognitive maps that ground our metaphors and provide the conceptual substrate for our most abstract thoughts are very much influenced by our bodily experiences of the world. Such an idea contradicts the view that the world can be objectively understood, as the properties we perceive are thus contingent upon the way our bodies interact with the world and on the metaphors we choose to model these interactions. The source domains of metaphor are usually grounded in concrete physical experience, whereas target domains tend to be more abstract. The extent to which particular spatial metaphors have pervaded our language is representative of the way our cognitive topologies dissect the world. For instance, up/down orientation metaphors (e.g., up is good, down is bad, top is best, bottom is worst, high is happy, low is sad) are considerably more productive than front/back metaphors (e.g., forward is future, back is past), which in turn are more productive than left/right metaphors (e.g., right is good, left is bad). From an objective stance, each spatial dimension possesses the same descriptive power. From a subjective position, however, we note that the paucity of left/right metaphors reflects the general symmetry of the human body in that direction; because left and right are so topologically undifferentiated, this dimension is utilized less in an egocentric model of the world. However, this symmetry does not exist in either the front/back or up/down dimensions. The fact that vision operates to the front of the body and not to the back is reason enough for this dimension to be differentiated, and thus descriptively useful, while the presence of an active force, gravity, acting in the vertical dimension justifies the significance we attach to the concepts of up and down. Metaphor enables our partial knowledge of a relatively abstract phenomenon to be organized into a coherent image-schema or gestalt structure using a more concrete source, which facilitates reasoning and communicating about that phenomenon (Lakoff and Johnson, Metaphor 56-68). In conceptual metaphor, these mappings are asymmetrical, which means that abstract domains are not used to conceptualize domains that are already fairly concrete. For example, “spring is still a long way off” and “the millennium is finally behind us” express the conventional metaphor TIME IS SPACE, with physical space as the source and time as the target. In this way of conceptualizing time, future events are in front of a person, past events are behind, physical distance correlates with the “amount” of time between two events, and so on.4 Third, conceptual metaphors are categorical. In Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things, Lakoff argues that social, psychological, and cosmological domains, conceptualized metaphorically, are taken as literally true by participants in a culture, and structure normal, unreflective thinking. He shows that Western philosophers and scientists have traditionally See “Chapter 10” in Lakoff and Johnson’s Philosophy in the Flesh: The Embodied Mind and its Challenge to Western Thought (New York: Basic Books, 1999). 4 conceptualized analytical categories as containers. In this metaphor, the properties of a container as a bounded, physical entity are used not only to describe, but also to reason about, the classification of entities in the world. The world does not necessarily have this structure, but CATEGORIES ARE CONTAINERS is so deeply embedded in Western culture that it is often assumed without introspection to represent objective reality “out there” in the world. To put this another way, what is implied by conventional metaphors defines what we can know, and we are thus enabled to reason about a target domain using the structure of the mapped source domain. Therefore, it is nearly impossible to think about most of our basic concepts without metaphor. Our literal understandings of concepts such as life, love, time, communication, causation, self, and cosmos are actually quite impoverished. Metaphor helps us flesh out these concepts so we can think about them in more detail (Lakoff and Johnson, Philosophy 128). In Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things, Lakoff further demonstrates that human beings categorize perceptual input into kinds of experience. Much of our direct experiential knowledge is organized in mental imagery as basic-level categories that represent the most inclusive level of abstraction to be represented by a concrete image in the mind.5 Lakoff and Turner argue that experience is made possible and structured by preconceptual structures—“directly meaningful concepts” roughly the same for all human beings—that thus provide “certain fixed points in the objective evaluation of 5 Basic-level categories maximize the correlational structure of our direct interactions with the world, and are the first categories to be learned and named by children. See E. Rosch, C.B. Mervis, W. D. Gray, M Johnson, and P. BayesBraem, “Basic Objects in Natural Categories,” Cognitive Psychology 8 (1976): 382-439. situations” (Lakoff and Turner 129). He divides them into basic-level structures and image-schema structures, and acknowledges there may be other kinds. Basic-level structures arise as a result of our capacities for gestalt perception, mental imagery, and motor movement and manifest as basic-level categories such as hunger and pain, wood and stone, people and cats, and tables and houses. Image schemas are spatial mappings such as source-path-goal, center-periphery, and container. It is out of these basic cognitive tools that more complex cognitive models of reality are constructed. More complex categorizations that organize a mature person’s knowledge consist largely of subsets and supersets of basic-level categories. In English, chairs and birds are basic-level categories because the average person can conjure up a mental image of a prototype for these concepts. Furniture and animals, in contrast, are superordinate-level categories because there is no single prototype for these concepts that can be imagined in the mind. It turns out that metaphorical expressions utilize basic-level categories that are easy to imagine, while the actual metaphorical concepts that generate these varied expressions occur at the superordinate level. For example, in linguistic expressions of LIFE IS A JOURNEY, such as “my plans have been derailed,” the life is usually described as a car, train, boat, or plane attempting to reach a destination, but the general mapping from which all these specific expressions derive involves the superordinate category vehicle. In light of this contingency, Lakoff argues for a subjective psychology that rejects classic models and proposes instead a non-reductionist model of natural categorization, one that replaces such staples of objectivism as necessary and sufficient conditions with prototypes, hedges, radial categories and idealized cognitive models. The basic notion underlying a radial category is that some members of a category will be more representative than others; taken together, the members of a category thus form a radial structure, the most representative, or prototypical, members located at the center, with less representative members clustered around this hub. For instance, a robin is a bird par excellence, while a penguin is quite a poor example of the class. Membership of a category is therefore a gradated notion, rather than an absolute, black-and-white one. Hedges are a form of category membership that correspond to linguistic judgments such as “kind of” or “sort of”; for instance, a whale is like a fish (sort of), and a moped is like a motorbike (kind of), inasmuch as many of the same common-sense inferences hold about each. Lakoff suggests that radial categories and prototypical effects arise due to a tendency in humans to conceptualize the world through partial and idealized cognitive models. Each category is defined relative to such a partial model, which captures the expectations that should hold whenever the category finds valid application. The degree to which the background idealized cognitive models of a category thus fits a real world entity or situation is a measure of the category representativeness of this entity/situation. Fourth, both target and source domains are projected into a new “blended space.”6 “Blending” or “mental binding” are conceptual integration, which is “is a basic mental operation whose uniform structural and dynamic properties apply over many areas of thought and action, including metaphor and metonymy” (Turner and Fauconnier 136). The two-space model of metaphor has been the cornerstone of the metaphor field since Aristotle, and has It is called “middle spaces” in G. Fauconnier and M. Turner, Conceptual Projection and Middle Spaces (La Jolla: UCSD Department of Cognitive Science, 1994). 6 underpinned a string of conceptual theories from Nietzsche, through Lefebvre, to Lakoff and Johnson. These theories posit a metaphor to concern the interaction of two conceptual spaces: the space that is described by the metaphor and has variously been termed the target, the tenor or the topic, and the space that provides the description and has been called the vehicle or the source. Lakoff’s works have developed into the cognitive foundations of conceptual integration and blended mental spaces, but Mark Turner and Gilles Fauconnier’s elaboration provides a unifying umbrella framework for a range of cognitive “siblings” that have traditionally been studied with relative independence, especially metaphor, analogy, and concept combination. The conceptual integration framework of Turner and Fauconnier augment the traditional input spaces with two additional spaces: a generic space that captures the common background knowledge that unites the inputs, and an output blend space that contains the conceptual product of the integration. Generic space contains the low-level conceptual structures that serve to mediate between the contents of the input spaces, thus enabling them to be structurally reconciled. Structural reconciliation involves mapping the conceptual structure of one input space onto another so as to ascertain a coherent alignment of elements from each. For instance, we can reconcile the domains of Baseball Player and Actor by seeing baseball fields as theaters, sportswear as costumes, and games as plays. The process of blending can be understood as follows: first, there is a partial mapping of counterparts between two input spaces; second, a generic space maps onto each of the inputs; finally, the input spaces are partially projected onto a fourth space, the blend. Here, the generic space reflects some common structure and organization shared by the inputs. The shared structure and organization, usually more abstract, defines the core cross-space mapping between them. On the other hand, the blend has emergent structure not provided by the inputs and maintains new relationships that did not exist in the separate inputs. When set in the context of background cognitive and cultural models, these new relationships allow the composite structure projected into the blend to be viewed as part of a larger self-contained structure. The structure in the blend can then be elaborated in terms of its own logic. Turner and Fauconnier find a striking conceptual blend in the metaphorical expression—“If Clinton were the Titanic, the iceberg would sink”—which was circulated inside the Washington, D.C. Beltway during February, 1998, when the movie “Titanic” was popular and when President Clinton seemed to be surviving political damage from yet another alleged sexual scandal. Obviously, the blend has two input mental spaces—one with the Titanic and the other with President Clinton. However, according to the Turner and Fauconnier, “there is a partial cross-space mapping between these inputs: Clinton is the counterpart of the Titanic and the scandal is the counterpart of the iceberg” (138). In this example, there is a blended space where Clinton is the Titanic and the scandal is the iceberg, with the Titanic scenario as the source and the Clinton scenario as target. The cross-space mapping between the inputs is metaphoric. The organizing frame structure of this blend stems from the “Titanic” input space—a voyage by a big ship that tragically runs into something bigger, but the casual and event shape structure does not come from the source. Nor does it come from the “Clinton” input space—he seems to be surviving—the blend takes its causal and event shape structure. The structure derives from a generic space where the source will be reversed if it happens and the target shows only some sign of it: Clinton will survive after all. Contrary to what the source implies and beyond what the target suggests, the inference is constructed: Clinton will overcome the political iceberg he meets and will meet. What deserves our attention is that this inference in the blend stems neither from the source nor from the target. It is based on the structure in the generic space—Clinton will survive after all.