The Power of Language Experience for Cross-Cultural Reading and Writing

advertisement

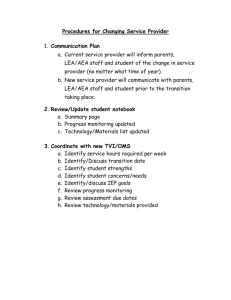

The Power of Language Experience for Cross-Cultural Reading and Writing David Landis, Joanne Umolu, Sunday Mancha “The Language Experience Approach can create opportunities for learning that bridge different languages, cultural expectations, and values about diverse events and life experiences.” from The Reading Teacher 63(7), 2010 Landis et al. 2010. the power of LEA Instructional Approach In this study, the team worked together with a group of primary-grade teachers to provide suitable texts for their classroom lessons by transcribing stories they told assisted junior secondary students with special needs by listening to them tell about important events in their lives and recasting their stories in the form of news bulletins Landis et al. 2010. the power of LEA Research Questions How can the diverse interests of students be satisfied in classroom reading and writing lessons? How can reading and writing instruction be adapted to promote more favorable education for students from different cultural backgrounds and life experiences? How could a reading curriculum be organized differently to build on students’ diverse language and life experiences and address topics that are mandated by educational standards and school curriculum plans? Landis et al. 2010. the power of LEA Definition of LEA Language Experience Approach (LEA) incorporates students’ retellings of home and community events to create reading materials for instructional purposes; focuses on students’ descriptions of their life experiences and written transcriptions about these events for use in reading and writing instruction. Landis et al. 2010. the power of LEA Precursor of LEA: Pestalozzi (Europe) Swiss educator Johann Pestalozzi (1746–1827) Favored object teaching, which uses students’ understandings and experiences as sources of knowledge rather than memorizing facts and principles. Was interested in providing opportunities for students who struggled with school reading and writing, especially students who had little or no access to education because their families could not afford to pay for it. Arranged “field trips” to observe and experience the aspects and characteristics of everyday objects. Students, for example, would investigate an object such as a wooden post and discuss how to describe some traits associated with it, such as color, texture, substance, height, and width. Landis et al. 2010. the power of LEA Precursor of LEA: John Frost (America) John Frost (1800–1859) incorporated Pestalozzi’s teaching practices into illustrated composition books in which students wrote objects’ descriptions or narrative accounts of personal experiences related to the illustrations. Frost’s (1839) Easy Exercises in Composition: Designed for the Use of Beginners contained Landis et al. 2010. the power of LEA Precursor of LEA: John Frost Students were invited to describe the simple objects, places, and scenes of their lives; to write about farming and fishing and manufacturing and shop keeping; to recount their own experiences of friends, family, school holidays, and reading and writing. to give their point of view in this writing, that is, they were asked to give their thoughts on a subject. (Schultz, 1999, p. 158) Landis et al. 2010. the power of LEA LEA in the 60’s and 70’s U.S. educators’ interest in language experience rose significantly by the 1960s and 1970s, and more research reviews were published about language experience teaching practices. An increasing number of doctoral dissertations investigated and discussed applications of language experience in elementary and secondary classrooms as well as postsecondary vocational education settings. Interest and research about language experience increased so rapidly that this approach to teaching reading and writing became the focus of IRA’s first special interest group in 1969 (Hall, 1978; Stauffer, 1980 Landis et al. 2010. the power of LEA LEA L2 Learners We view LEA as appropriate for cross-cultural reading instruction in multilanguage settings where students’ differing values, beliefs, and ways of living are brought into contact. We use the term cultural to refer to habits of using time, space, and language; modes of dress; and routine ways of participating in formal and informal events in work and play settings and societal institutions, as well as in family and community social roles and activities. Cross-cultural means looking at these ways of life from the perspectives of members of a cultural group, as well as from the perspectives of those outside the group. Landis et al. 2010. the power of LEA LEA L2 Learners LEA provides opportunities for students from diverse backgrounds to build vocabulary and spelling proficiency, participate in phonics analysis, develop reading comprehension, foster creative writing, and make connections between reading and writing, along with other educational benefits. Landis et al. 2010. the power of LEA The LEA Workshop in Nigeria The focus of this workshop was to develop bilingual Hausa–English narratives and informational texts for students in grades 4–6 who are beginning to read English. In our roles as volunteer consultants and trainers, we were invited by IRA to work with the Sabon Gari local education officials and local university teacher education faculty members to plan and prepare materials for the workshop. We facilitated activities during the workshop and also assisted teachers as they applied ideas from the workshop in their classrooms. Landis et al. 2010. the power of LEA “News on the Board” for L2 Learning Disabled Children A classroom-based adaptation of LEA which draws on the experiences and spoken language of students as they dictate their news to the teacher, who transcribes what students say in the form of news bulletins. Procedures Ss’ news report T transcription of the news Read-alouds of news report Vocabulary matching and collection Storybook making Landis et al. 2010. the power of LEA LEA: Criticisms and Responses Criticism #1: Educators believe that routine use of language experience inhibits readers from developing a range of interests and familiarity with a variety of narrative and informational materials (Spache & Spache, 1977). Response: Teachers using an LEA have been able to create many different types of written materials, including stories and interviews about various events, scripts, recipes, charts, lists for planning future activities, drawing and labeling of maps and diagrams, directions for repairing and making things, and other types of written, audio, and visual texts. Landis et al. 2010. the power of LEA LEA: Criticisms and Responses Criticism #2: LEA lacks sufficient published materials to provide enough structure and organization for lessons, curricular guides, or assessments accompanying the approach. Response: There have been published materials that provided guidance in planning, record keeping, and student progress evaluation. Materials and suggestions about ways to incorporate language experience into lessons and evaluation activities have been developed. Landis et al. 2010. the power of LEA LEA: Criticisms and Responses Criticism #3: “Language experience is not an easy way to teach reading. It demands flexibility in classroom management, recognition of individual differences in language development, personalized record keeping and teacher skill in...evaluation. Children must be helped to acquire the ability to work independently and cooperatively in small groups in this method, too. (Spache & Spache,1977, p. 135) Response: Although LEA has been criticized for requiring too much flexibility, we find that teachers also recognize that LEA actually helps students gain valuable experience with reading and writing from multiple vantage points and perspectives within and outside of stories. Landis et al. 2010. the power of LEA