A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE ON MANAGEMENT COMPETENCIES IN THE

advertisement

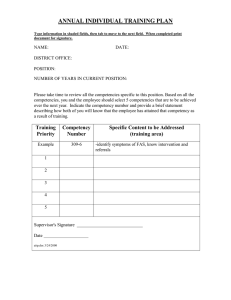

A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE ON MANAGEMENT COMPETENCIES IN THE SPORTS INDUSTRIES A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE ON MANAGEMENT COMPETENCIES IN THE SPORTS INDUSTRIES Ling-Mei Ko Department of Leisure, Recreation, and Tourism Management, Southern Taiwan University Tainan, TAIWAN E-mail: lmko@mail.stut.edu.tw Abstract. Competency studies with the aim to determine the knowledge and skills needed to perform a job have been a major research area in sports management. This paper introduces a “Systematic Review” approach to undertake a literature review on management competencies required for sports industry which will contribute to an understanding of competencies research in sports management field. Keywords: Competency, Sports Management, Systematic Review 1 INTRODUCTION The sports management industry is growing worldwide with an expansion in employment potential and academic preparation programmes. It is believed that in order to prepare competent sports managers adequately, the requisite competencies must first be identified. As a result, competency studies with the aim to determine the knowledge and skills needed to perform a job have been a major research area in sports management and have received attention from a wide range of scholars. The aim of this paper is thus to introduce a “Systematic Review” approach to review literature on management competencies required for sports industry which will contribute to an understanding of competencies research in sports management field. This paper starts with an overview of the systematic review method. Then it goes on to provide a step-by-step description of the processes involved in undertaking a systematic review in this study. 2 THE INTRODUCTION OF SYSTEMATIC REVIEW Conducting a review of literature is an essential and important part of any research study. The aim of a literature review is to understand the existing intellectual field, and to identify research questions for developing or investigating the existing knowledge further. However, the traditional literature review has been criticised for a lack of thoroughness[1] and for employing a “ “biased” sample of the full range of the literature on the subject” . Torgerson[2] argues that the selection of papers to be included or excluded in a traditional literature review is often not made explicit and may reflect the biases of the reviewer because the decision to select material for inclusion is usually made by the reviewer who gathers and interprets the studies. The systematic review; on the other hand, offers a more explicit alternative methodology for a literature review. The systematic review methodology was initially developed in the medical sciences where it has been used to summarise all the available evidence, normally to assess the effect of a treatment. It differs from traditional narrative or descriptive reviews by adopting a transparent and replicable audit trail of decision making and procedures throughout the reviewing process[1]. This means that anyone using the same reviewing process should end with the same search results. Systematic reviews follows a review protocol to synthesise the findings of a great amount of primary studies employing several “strategies” to minimise bias by the reviewer such as the use of expert-identified keywords and databases and the use of explicit criteria in the inclusion of articles for review. There are three main stages suggested to be conducted in a systematic review[1]. Table 1 outlines the stages which should be conducted in a systematic review. Table 1: Stages of Systematic Review Stage Phase Stage 1─ Planning the Review Form a review panel Phase 0 – Identification of the need for a review Phase 1 – Preparation of a proposal for a review Phase 2 – Development of a review protocol L.M.Ko Phase 3 – Identification of research Phase 4 – Selection of studies Phase 5 – Study quality assessment Phase 6 – Data extraction and monitoring progress Phase 7 – Data synthesis Stage 3 ─ Reporting Phase 8 – The report and recommendations and Dissemination Phase 9 – Getting evidence into practice Source: Transfield et al. [1] Stage 2─ Conducting a Review Stage 1─ Planning the Review The first stage of conducting a systematic review is planning the review. The purpose of forming a review panel is to hold regular meetings in order to direct the reviewing process and discuss disputes over the inclusion and exclusion of studies. Review panel members should include experts in methodology and theory, and practitioners working in the field. An initial scoping study is conducted at this stage with the aim at establishing a brief overview of the related topics in the field, including theoretical, practical, and methodological history and key discussions [1] . Following these actions, a review protocol is formed. A review protocol is a plan providing explicit descriptions of each step which will need to be taken, allowing the reviewer to conduct the review with minimal bias, and ensuring greater efficiency in the review process. It should include the specific questions discussed by the study, the sample and search strategy adopted by the study, and the criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies. These elements should be transparent enough to allow anyone else to repeat the process. Although a review protocol is set up at the initial stage, the protocol can still be modified through the review process, but the reasons for any such modification should be explicitly stated. Stage 2─ Conducting a Review The main feature of a comprehensive, unbiased systematic review is that the search strategy must be addressed in sufficient detail to allow replication. It should include information concerning each step taken in the search. The first step is to identify appropriate databases to be searched for relevant articles. Electronic databases render searching much more systematic and efficient, though they have the limitation that most databases include only abstracted journal articles and thus a significant limitation is that books and book chapters are excluded, after the initial ‘manual’ search for the scoping study. Clearly a limitation of the systematic review procedure is that it can exclude reports and other grey literature, together with books and book chapters (depending on the databases searched). However, in the scoping exercise which preceded the systematic review proper, such items were included where available. Inclusion in the expert panel of an information scientist or an expert in relation to the literature in the field is thus important if appropriate selection of databases is to be achieved. After databases have been selected, choice of search terms, key words and search strings are required. Here again some knowledge of the strengths and weaknesses of search strategies for particular databases is required. Then, a full listing of articles and papers should be made which consists of all output of this search. Only a study which meets all inclusion criteria decided in the review protocol will be incorporated into the review. As the decision of inclusion and exclusion can be a relatively subjective process, the review panel should be closely involved through the process. The researcher initially conducts an overview of the full list of references identified in the search. In order to assess inclusion status, relevant sources will be retrieved and the abstract or full text will be reviewed. At this point, each exclusion made is reported with reasons for exclusion. Such reasons might include that an article is not relevant to the subject or the article is not in English. The data-extraction process requires documentation of all steps taken which aims to provide a historical record of decisions made during the review process. Tranfield et al.[1] mention that systematic reviews employ dataextraction forms in order to reduce human error and bias. Moreover, double-extraction procedures may be employed by two independent researchers and results compared and reconciled, if required. A primary aim of the protocol is thus replicability (any researcher employing the same criteria would arrive at the same sample of literature to review), transparency and accountability (all decisions are explicit and need to be defended), and auditability. The final stage is to report the findings of a systematic review. A well-conducted systematic review should synthesise extensive primary research findings in a manner which will allow for readers to easily understand the research. A twostage report is proposed to be made within management research[1]. The first is a ‘descriptive analysis’ in gathering the basic data of research papers such as the name of authors, title, and abstract. The second is a ‘thematic analysis’ which references the broad themes apparent across the literature reviewed. The reporting should focus on L.M.Ko linking themes which range across various core contributions. In relation to the topic of management competencies in the sport industry, despite the significant number of studies that have been conducted in this field, little attempt has been made to translate these findings into a comprehensive review of current knowledge. Hence, a systematic review was executed with the aim at exploring all aspects of the existing literature and empirical evidence relating to management competencies and their relative importance in sports management. This would then provide a basis on which to develop a methodology for the investigation of competencies in the Taiwanese sports industry. 3 THE SYSTEMATIC REVIEW PROCESS The following section will describe the stages conducted in this systematic review. Stage 1─ Planning the Review Step 1: Forming a Review Panel The members of a review panel were chosen based on their background to encompass the expertise related to the field of study, to information services and also their involvement within the PhD process. The panel members include the author of this paper, Professor Ian Henry who works in the Institute of Sports and Leisure Policy at Loughborough University, and Louise Fletcher who is a librarian specialized in sports at Loughborough University. The first panel meeting was held on 18 August, 2005. During the meeting, the panel identified the aim of the systematic review, the appropriate databases and key terms. Subsequent discussions in the group were conducted by both face-to-face meetings and via email discussion. This will be discussed later. Step 2: Mapping the Field of Study In order to gain a broad perspective of the field and to clarify and delimit the aims and objectives of the review, a process of literature mapping was undertaken. This so- called ‘scoping study’ included a brief overview of the concept of competency. Step 3: Developing a Review Protocol The systematic review aims to answer the following question: ‘What are the important professional and managerial competencies to the successful conducting of a sports manager’s job?’ In order to achieve focus in the review, the panel decided, in relation to the search strategy, to combine several keywords. Furthermore, core criteria for inclusion and exclusion were established: (1) time frame: 1985-2005; (2) academic relevance to the topic; (3) language in English; (4) pages: 3 pages or more. Stage 2─ Conducting a Review Step 4: Identification of Research First, a number of keywords relating to the competencies of sports managers were identified by the panel based on their prior experience (Table 2). Table 2: Keywords Sports Management Competency Skill Job analysis Task analysis Role analysis Marketing Finance Human resource Person specification Occupational personality Work profile Job description Education Curriculum Programme Course However, in order to reduce volume and increase relevance, the panel decided to combine keywords into search strings rather than use a single keyword. There were 8 search strings identified (Table 3). Table 3: Combinations of Keywords 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 sport* AND manag* AND (job analysis OR task analysis OR role analysis) sport* AND manag* AND (skill* OR competenc*) sport* AND manag* AND (skill* OR competenc*) AND (finance OR marketing OR human resource) sport* AND manag* AND (work profile OR job description OR person specification OR occupational personality) sport* AND manag* AND (education OR curricul* OR program* OR course*) AND (job analysis OR task analysis OR role analysis) sport* AND manag* AND (education OR curricul* OR program* OR course*) AND (skill* OR competenc*) sport* AND manag* AND (education OR curricul* OR program* OR course*) AND (skill* OR competenc* ) AND (finance OR marketing OR human resource) sport* AND manag* AND (education OR curricul* OR program* OR course*) AND (work profile OR job description OR person specification OR occupational personality) As for the databases, the panel identified 14 databases to search for keywords based on the L.M.Ko relevance to sports and management fields (ABI Research (OCLC), ALTIS, ASSIA (CSA Illumina), Article First (OCLC), Emerald Fulltext, Google scholar, IBSS (BIDS), Leisuretourism.com, PsycINFO (CSA Illumina), Science Direct, SOSIG, SportDiscus, Web of Science, and Zetoc). When applying the keyword strings in databases, some databases did not have any result or the results were not relevant to the study. These included ALTIS, ASSIA (CSA Illumina), Google scholar, PsycINFO (Illumina), and SOSIG, and Zetoc. Therefore, the 14 databases were reduced to 8 (Table 4). Table 4: Databases Article First (OCLC) ABI Research (OCLC) Emerald Fulltext IBSS (BIDS) Leisuretourism.com SportDiscus Science Direct Web of Science After keyword combinations and databases were finally defined, a search was performed by entering keyword combinations in each database during September and October 2005. Step 5: Evaluation of Studies The title and abstract of all papers from the results of searches were screened for inclusion by one reviewer (Ling-Mei Ko). If there was any indecision, it would be brought for discussion with another reviewer (Professor Ian Henry). This manual inclusion and exclusion was based on the criteria agreed by the panel. A full copy of all identified articles was then retrieved. It is acknowledged that at this stage the decision of inclusion based on academic relevance and the decision to subject a choice to exclude to further discussion with another reviewer were relatively subjective. Step 6: Conducting Data Extraction The systematic literature search was conducted on 8 databases, from which 1193 results were returned. A data-extraction form was created to present details of these returned results (Table 5). The number of results was then reduced to 1113 documents by eliminating duplication. After the assessment of each result, 128 documents were identified for further examination and the full articles were reviewed for relevance. Table 5: Data Extraction Statisitcs Databases ArticleFirst (OCLC) ABI Research (ProQuest) Emerald Fulltext IBSS (BIDS) Total 8 235 24 3 Included 1 5 2 0 Leisuretourism.com SPORTDiscus Science Direct Web of Science sub-total (duplication) Total 274 564 2 83 1193 80 1113 39 94 0 4 145 17 128 Step 7: Conducting Data Synthesizing After extracting data, the next step is data synthesising. Data synthesising is aimed at achieving a greater level of understanding of the field of study by summarising and integrating relevant studies. The knowledge generated through the review is reported in the following section. Stage 3─ Reporting and Dissemination Step 8: Reporting Findings 1. Definition and Dimensions of Competency Competencies are generally used as a hiring criterion, a training plan, and a framework for evaluation [3,4]. The term ‘competency’ has been defined in a variety of ways in the literature. In general, the term competency implies that an individual must have a specific ability or capability needed to perform a particular job effectively[5,6]. Many researchers indicate that competencies should include skills, knowledge and personal characteristics. A competency consists of two elements which are “the actual performance of a required skill” and “the personal attributes which underline such performance”[7: 99]. Lambrecht[8] defines a competency as a knowledge, skill or attitude needed to carry out properly an activity to succeed in one’s professional life. In addition, competencies include certain motives, traits, skills and abilities that are attributed to an individual who behaves in specific ways consistently[9]. Koustelios[10] highlights a competency as an essential characteristic of an individual to perform a job effectively. Furthermore, the term ‘competency’ is also defined as unconscious personal characteristics and traits which include motivations, values and attitudes[7]. Drawing on such approaches, for the purposes of this study the following definition of a competency will be used. The definition thus focuses on skills and knowledge rather more than the more tenuous concerns with attitude. ‘Competencies are the combination of knowledge, skills, abilities, and personal traits which are utilised to perform a variety of activities and behaviours effectively’ L.M.Ko 2. Overview of Competency-Based Approach Boucher[11] notes that in the field of management study there has been a significant movement towards a competency-based approach. As a result, the competency-based approach to management has generated much attention in recent years. Horch and Schutte[12: 71] describe “the competency-based approach as drawing on the knowledge of current practising managers”. There are two main contributions of the competency-based approach. One contribution is to gain knowledge of a particular profession by identifying the knowledge and skills needed for an individual to perform in a particular professional role[3,8,11,13,14]. The other contribution is to be predicated on education. McLagan and Bedrick[15] state in Birdir and Pearson [16: 205] that a “competency study is a major step toward professionalisation of the very important field of training and development”. First, competencies can be used for curriculum design in order to educate students with the necessary skills and knowledge of the various occupations. Second, the identification of job-specific competencies can be utilised as a basis for in-service training. Third, competencies can also provide guidelines for individuals who want to build up their own ability to enter this field. Dubois[17] concludes that the development of competency models is crucial to the development of competency-based performance and curricular plans. Many researchers have acknowledged the development of competency-based education in sports management. Since, sport industries have experienced expansion over recent decades, much research has been needed to ensure that people are trained appropriately to effectively manage the various components of the sports industries in the future[18-21]. As academic preparation programmes in sport management began to proliferate on college and university campuses, competency studies have become one of the most important research areas in determining the body of knowledge needed to prepare competent sports managers in so called competency-based education[13,22-28]. In addition, Ellard[22] has stressed that the difference between competencybased education (CBE) and a traditional approach to learning is that the learning tasks of CBE are not copied from textbooks, but are based on identifying specific competencies needed by the learner to accomplish the tasks at hand. It seems likely that the competency approach to the sports management will continue to be a trend of note in the 21st century. 3. Competencies Research in Sports Management Specific competency-based studies in sports management include, but are not limited to, the studies summarised in Table 6. Table 6: List of Competencies Research in Sports Management Year Authors Nation 1980 Jamieson U.S. 1984 Jennings U.S. 1985 Ellard U.S. 1986 Parks and Quain U.S. 1987 Davis U.S. 1987 Hatfield, Wrenn, and Bretting U.S. 1987 Lambrecht U.S. 1989 Farmer Australia 1990 Skipper U.S. 1990 Coalter and Potter U.K. 1991 Cuskelly and Auld Australia 1993 Afthinos Greece 1993 Chen Taiwan 1993 Cheng Taiwan 1993 Tait, Richins, and Hanlon Australia 1993 NASPE-NASSM U.S. 1995 Irwin, Cotter, Jenson, and White Australia 1995 Nikolaidis Europe 1997 Kim Korea 1997 Toh India 2000 Peng U.S. 2003 Case and Branch U.S. 2003 Horch and Schutte German 2004 Barcelona and Ross U.S. Step 9: Getting Evidence into Practice An understanding of relevant competency research conducted in sports management not only provides the insights into the issues surrounding the competency-related field in sports management, but also helps to define the research problem, research purpose and research methods of this study. The studies reviewed in this systematic review present several points of interest. First, although much research has been conducted in the required competencies of a sports manager, most previous studies suffer from two main deficiencies. The first deficiency is that most of previous studies regarding sports management competencies were mainly focused on a particular setting, such as collegiate athletics[28-30], sports clubs[8,12,31], sports centres [32], sports facility settings[13,33,34], and sports events[13]. Since the settings are different, it is not expected that there will be similar and generic competencies for all. Although Barcelona and Ross[28] argue that sports management L.M.Ko professionals working in different settings often require different skills and knowledge, other researchers have argued that sports managers must possess generalised skills to be able to adapt to many types of settings[8,14]. Moreover, sports management programmes are often not aimed to train their students only for a particular sports setting although we do see increasing specialisation, in the UK with for example sport event management; sport development degrees. Instead, sports management curricula tend to be designed to educate students with necessary competencies to perform a sports management role in a variety of managerial settings. As a result, it is important to conduct more competency studies within a wide range of settings in order to determine if the competencies are generalisable across such settings. The second deficiency is that there is a methodological weakness in current competency studies in the sports management field. Most competency studies utilise quantitative survey techniques which it has been argued limit the responses of respondents in a simple checklist. Therefore, many researchers suggest survey based research should not be the only method used in competency studies, additional data collection techniques such as the Delphi method, focus group, or multi-method triangulation procedures, it is argued, should be used to validate the findings of the research in this field[28,35]. While there have been many studies investigating the perceptions of important competencies of a sport manager, there have been none to date that specifically look at studies in relation to national context. Culture and context will be significant in respect of what competencies are required and what competencies are perceived as important by practitioners and academics. Taking this perspective into consideration, we seek to identify if competencies are perceived differently across regions of the world. In an examination of 24 competency-based studies in English on sports management shown in Table 6, we are also able to access the cultural context of the reviewed competency research. By region, there were 12 studies conducted in the United States, 4 in Europe, 4 in Australia, and 4 in Asia identified within our systematic review. Table 7 presents the ranking of competencies with respect to referenced frequency in studies by region. Referenced frequency of a competency represents how many studies identified it as a critical competency required by a sports manager. There were certain similarities and differences in the ways respondents from U.S., Europe, Australia, and Asia perceived competencies. Communication and human resource management are perceived as highly significant across all regions. Facility management, sports-related theory and foundations, first aid and safety prevention, and administration skills while considered as important competencies across all regions, were not as significant in the Australian studies as in the other three regions. In the European rankings, some competencies were perceived as less important compared to the other regions, for example, information technology and writing skills. In addition, public speaking is a competency favoured in Asia but less highly regarded in the US, Europe and Australia. The discussion supports the notion that for these 24 studies at least, the importance of competencies is perceived differently from region to region. We have taken a global perspective, but the fact that most studies examined were conducted in the US may have biased our results to favour competencies in the US context. In addition, the systematic review not only reviews studies from different countries but across the period from 1980 to 2005. The ranking of competencies by published year using a similar format to that of Table 7 is presented in Table 8. It is not surprising to find the continuous emphasis on basic business managerial competencies such as communication, management techniques, administrative skills, human resource management, marketing, accounting, and budgeting. Also, particular competencies related to the context of sports management were also emphasised over time which included sportsrelated theory and foundations, research in sports, facility management, event management, first aid and safety prevention, and programming techniques. The analysis also presented some insights into the competencies emphasised during different periods. There were several new management topics emerging in importance in the 1990s and the early 2000s which included risk management, crisis response and stock management. In addition, a growing emphasis was found on the importance of information technology and financial competencies such as financial management, fund raising and sponsorship, and economics. However, emphasis on supervision skills, and controlling and monitoring was found to decline after the 1990s. The growing emphasis on flatter, non-bureaucratic structures in the management literature might be expected to reduce the emphasis on those skills associated with bureaucratic procedures. However, the importance of interpersonal skills seems to have L.M.Ko been enhanced, for example in relation to human relations, coordinating, and conflict resolution. Although there were only 24 studies selected to examine the influence of culture and time on the perceptions of competencies, the discussion suggests that the perceptions of competencies may differ from region to region and over time. Thus, it is suggested that further research should take these considerations into investigating the competencies. 4 CONCLUSION From the development of this systematic review we are able to identify and reflect on three key themes. The first is to summarise the range, type and frequency of skills and competencies identified as significant. The second is the identification of the cultural context of the competency research conducted. The third is to identify the changes globally in terms of competencies that emerge or decline in importance over time. REFERENCES [1] Tranfield, D., Denyer, D. and Smart, P., 2003. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review, British Journal of Management, 14(3): 207-222. [2] Torgerson, C., 2003. Systematic Reviews, London: Continuum. [3] Hurd, A. and McLean, D., 2004. An analysis of the perceived competencies of CEOs in public park and recreation agencies, Managing Leisure, 9(2): 96-110. [4] MacLean, J., 2001. Performance appraisal for sport and recreation managers: Human Kinetics Publishers. [5] Frisby, W., 2005. The good, the bad, and the ugly: Critical sport management research., Journal of Sport Management, 19(1): 1-12. [6] Tungjaroenchai, A., 2000. A Comparative Study of Selected Sport Management Programs at the Master's Degree Level. University of Oregon., Unpublished doctoral dissertation. [7] Birkhead, M., Sutherland, M. and Maxwell, T., 2000. Core competencies required of project managers, South African Journal of Business Management, 31(3): 99-105. [8] Lambrecht, K.W., 1987. An analysis of the competencies of sports and athletic club managers, Journal of Sport Management 1(2): 116-128. [9] Perdue, J., Ninemeier, J.D. and Woods, R.H., 2002. Comparison of present and future competencies required for club managers, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 14(3): 142-146. [10] Koustelios, A., 2003. Identifying important management competencies in fitness centres in Greece, Managing Leisure, 8145-153. [11] Boucher, R.L., 1991. Enlightened management of sport in the 1990s - a review of selected theories and trends; sport for all. In: The world congress on sport for all, pp. 517-526, Tampere, Finland. [12] Horch, H.D. and Schuette, N., 2003. Competencies of sport managers in German sport clubs and sport federations., Managing Leisure 8(2): 70-84. [13] Peng, H., 2000. Competencies of Sport Event Managers in the United States. University of Northern Colorado., Unpublished doctoral dissertation. [14] Jamieson, L.M., 1991. Competency requirements of future recreational sport administrators. In: Management of recreational sport in higher education (Boucher, R.L. and Weese, W.J., eds.), pp. 33-46. [15] McLagan, P. and Bedrick, D., 1983. Models for excellence: The results of the ASTD training and development competency study, Training and Development Journal, 37(6): 10-20. [16] Birdir, K. and Pearson, T.E., 2000. Research chefs' competencies: A Delphi approach, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 12(3): 205-209. [17] Dubois, D.D., 1993. Competency based performance improvement., Amherst: MA: HRD Press. [18] Tait, R., Richins, H. and Hanlon, C., 1993. Perceived training needs in sport, recreation and tourism management., Leisure Options: Australian Journal of Leisure and Recreation, 3(1): 12-26. [19] Cunneen, J., 1992. Graduate-Level professional preparation for athletic directors., Journal of Sport Management, 6(1): 17-20. [20] Hogg, D., 1989. Professional development needs of sports administration. In: Management and Sport Biennial Conference, Canberra University. [21] Hanlon, C., Tait, R. and Rhodes, B., 1994. Management styles of successful sport, tourism and recreation managers., Leisure L.M.Ko [22] [23] [24] [25] [26] [27] [28] [29] [30] [31] [32] [33] Options: Australian Journal of Leisure and Recreation, 4(2): 23-30. Ellard, J.A., 1985. A Competency Analysis of Managers of Commercial Recreational Sport Enterprises. Indiana University, Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Parks, J.B. and Quain, R.J., 1986. Curriculum perspectives., Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 57(4): 22-26. Quain, R.J. and Parks, J.B., 1986. Sport management survey: employment perspectives., Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 571821. Jamieson, L.M., 1987. Competency-based approaches to sport management., Journal of Sport Management, 1(1): 48-56. Ulrich, D. and Parkhouse, B.L., 1982. An alumni oriented approach to sport management curriculum design using performance ratings and a regression model., Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 53(1): 64-72. Bontigao, E.N., 1995. Competencies Needed to Assume the Role of Director of Morale, Welfare, Recreation and Commumity Activities Services. Temple University, Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Barcelona, B. and Ross, C.M., 2004. An analysis of the perceived competencies of recreational sport administrators., Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 22(4): 25-42. Jennings, W., 1984. Entry level competencies for recreational sports personnel as identified by chairs of preparatory institutions. North Texas State University, Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Hatfield, B.D., Wrenn, J.P. and Bretting, M.M., 1987. Comparison of job responsibilities of intercollegiate athletic directors and professional sport general managers., Journal of Sport Management, 1(2): 129-145. Davis, K.A., 1987. Selecting qualified managers: Recreation/sport management in the private sectors, Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 58(5): 81-85. Kim, H.S., 1997. Sport Management Competencies for Sport Centers in the Republic of Korea. United States Sports Academy, Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Skipper, W.T., 1990. Competencies for collegiate sports facility managers: Implication for a facility management curricular model. University of Arkansas, Unpublished doctoral dissertation. [34] Case, R. and Branch, J.D., 2003. A study to examine the job competencies of sport facility managers., International Sports Journal, 7(2): 25-38. [35] Cuskelly, G. and Auld, C., 1991. Perceived importance of selected job responsabilities of sport and recreation managers: An Australian perspective, Journal of Sport Management, 5(1): 34-46. L.M.Ko 1 2 3 4-8 4-8 4-8 4-8 4-8 9-10 9-10 11-12 11-12 13-15 13-15 13-15 16-20 16-20 16-20 16-20 16-20 21-23 21-23 21-23 24-25 24-25 26-27 26-27 28-33 28-33 28-33 28-33 28-33 28-33 34-37 34-37 34-37 34-37 38-41 38-41 38-41 38-41 42-46 42-46 42-46 42-46 42-46 47-52 47-52 47-52 47-52 47-52 47-52 53-58 53-58 53-58 53-58 53-58 53-58 Communication Facility Management Sports-Related Theory and Foundations Budgeting First Aid and Safety Prevention Human Resource Management Legal Aspects Marketing Administrative Skills Public Relations Financial Management Information Technology Accounting Event Management Self Management Decision Making Employee Relations/Labour Relations Management Techniques Programming Techniques Writing Skills Customer Relationship Management Evaluation skills Research in Sports Fund Raising and Sponsorship Governance Goal Setting Leadership Coaching Economics Problem Solving Public Speaking Purchasing Risk Management Field Experience in Sports Management Planning Resource Management Service Provision and Development Crisis response Coordinating Mass Communication/Mass Media Staff Meetings Ethics in Sports Management Language Management Theory Personal Fitness Sports Practice Foresight Human Relations Implement Negotiation Skills Organising Supervision Skills Conflict Resolution Controlling and Monitoring Personal Attributes Political Awareness Stock Management Training and Educating Referenced % Referenced Frequency (rank) Asia (N=4) Referenced % Referenced Frequency (rank) Australia (N=4) Referenced % Referenced Frequency (rank) Europe (N=4) Referenced % USA (N=12) Referenced Frequency (rank) Competency Referenced % Worldwide (N=24) Referenced Frequency World Rank Table 7: Summary of Critical Competences by Region 19 17 79% 71% 10 (1-3) 10 (1-3) 83% 83% 2 (7-12) 3 (1-6) 50% 75% 4 (1) 1 (15-30) 100% 25% 3 (1-8) 3 (1-8) 75% 75% 16 15 15 15 15 15 13 13 12 12 11 11 11 10 67% 63% 63% 63% 63% 63% 54% 54% 50% 50% 46% 46% 46% 42% 9 (4-6) 9 (4-6) 8 (7-10) 7 (11-14) 9 (4-6) 8 (7-10) 10 (1-3) 7 (11-14) 5 (19-23) 8 (7-10) 8 (7-10) 4 (24-29) 5 (19-23) 6 (15-18) 75% 75% 67% 58% 75% 67% 83% 58% 42% 67% 67% 33% 42% 50% 3 (1-6) 1 (13-36) 3 (1-6) 3 (1-6) 2 (7-12) 3 (1-6) 1 (13-36) 2 (7-12) 2 (7-12) 0 (37-58) 1 (13-36) 3 (1-6) 1 (13-36) 1 (13-36) 75% 25% 75% 75% 50% 75% 25% 50% 50% 0% 25% 75% 25% 25% 1 (15-30) 2 (5-14) 1 (15-30) 2 (5-14) 2 (5-14) 3 (2-4) 0 (31-58) 2 (5-14) 3 (2-4) 2 (5-14) 1 (15-30) 2 (5-14) 2 (5-14) 2 (5-14) 25% 50% 25% 50% 50% 75% 0% 50% 75% 50% 25% 50% 50% 50% 3 (1-8) 3 (1-8) 3 (1-8) 3 (1-8) 2 (9-23) 1 (24-47) 2 (9-23) 2 (9-23) 2 (9-23) 2 (9-23) 1 (24-47) 2 (9-23) 3 (1-8) 1 (24-47) 75% 75% 75% 75% 50% 25% 50% 50% 50% 50% 25% 50% 75% 25% 10 10 10 10 9 9 9 8 8 7 7 6 6 6 6 6 6 42% 42% 42% 42% 38% 38% 38% 33% 33% 29% 29% 25% 25% 25% 25% 25% 25% 7 (11-14) 6 (15-18) 6 (15-18) 6 (15-18) 5 (19-23) 5 (19-23) 7 (11-14) 3 (30-40) 5 (19-23) 4 (24-29) 4 (24-29) 4 (24-29) 4 (24-29) 3 (30-40) 3 (30-40) 3 (30-40) 4 (24-29) 58% 50% 50% 50% 42% 42% 58% 25% 42% 33% 33% 33% 33% 25% 25% 25% 33% 1 (13-36) 2 (7-12) 1 (13-36) 0 (37-58) 1 (13-36) 1 (13-36) 1 (13-36) 2 (7-12) 1 (13-36) 1 (13-36) 0 (37-58) 1 (13-36) 1 (13-36) 1 (13-36) 0 (37-58) 1 (13-36) 0 (37-58) 25% 50% 25% 0% 25% 25% 25% 50% 25% 25% 0% 25% 25% 25% 0% 25% 0% 0 (31-58) 1 (15-30) 2 (5-14) 3 (2-4) 1 (15-30) 2 (5-14) 0 (31-58) 1 (15-30) 1 (15-30) 0 (31-58) 1 (15-30) 0 (31-58) 0 (31-58) 1 (15-30) 0 (31-58) 0 (31-58) 0 (31-58) 0% 25% 50% 75% 25% 50% 0% 25% 25% 0% 25% 0% 0% 25% 0% 0% 0% 2 (9-23) 1 (24-47) 1 (24-47) 1 (24-47) 2 (9-23) 1 (24-47) 1 (24-47) 2 (9-23) 1 (24-47) 2 (9-23) 2 (9-23) 1 (24-47) 1 (24-47) 1 (24-47) 3 (1-8) 2 (9-23) 2 (9-23) 50% 25% 25% 25% 50% 25% 25% 50% 25% 50% 50% 25% 25% 25% 75% 50% 50% 5 5 5 5 4 4 4 4 3 3 3 3 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 21% 21% 21% 21% 17% 17% 17% 17% 13% 13% 13% 13% 13% 8% 8% 8% 8% 8% 8% 4% 4% 4% 4% 4% 4% 2 (41-46) 3 (30-40) 3 (30-40) 3 (30-40) 2 (41-46) 3 (30-40) 3 (30-40) 3 (30-40) 2 (41-46) 2 (41-46) 3 (30-40) 1 (47-52) 2 (41-46) 0 (53-58) 1 (47-52) 1 (47-52) 1 (47-52) 1 (47-52) 2 (41-46) 0 (53-58) 0 (53-58) 0 (53-58) 0 (53-58) 0 (53-58) 1 (47-52) 17% 25% 25% 25% 17% 25% 25% 25% 17% 17% 25% 8% 17% 0% 8% 8% 8% 8% 17% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 8% 1 (13-36) 1 (13-36) 1 (13-36) 1 (13-36) 0 (37-58) 0 (37-58) 0 (37-58) 0 (37-58) 0 (37-58) 1 (13-36) 0 (37-58) 0 (37-58) 0 (37-58) 0 (37-58) 0 (37-58) 0 (37-58) 0 (37-58) 0 (37-58) 0 (37-58) 0 (37-58) 1 (13-36) 0 (37-58) 1 (13-36) 1 (13-36) 0 (37-58) 25% 25% 25% 25% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 25% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 25% 0% 25% 25% 0% 1 (15-30) 1 (15-30) 0 (31-58) 0 (31-58) 0 (31-58) 0 (31-58) 0 (31-58) 0 (31-58) 0 (31-58) 0 (31-58) 0 (31-58) 0 (31-58) 0 (31-58) 1 (15-30) 0 (31-58) 0 (31-58) 0 (31-58) 1 (15-30) 0 (31-58) 1 (15-30) 0 (31-58) 1 (15-30) 0 (31-58) 0 (31-58) 0 (31-58) 25% 25% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 25% 0% 0% 0% 25% 0% 25% 0% 25% 0% 0% 0% 1 (24-47) 0 (48-58) 1 (24-47) 1 (24-47) 2 (9-23) 1 (24-47) 1 (24-47) 1 (24-47) 1 (24-47) 0 (48-58) 0 (48-58) 2 (9-23) 1 (24-47) 1 (24-47) 1 (24-47) 1 (24-47) 1 (24-47) 0 (48-58) 0 (48-58) 0 (48-58) 0 (48-58) 0 (48-58) 0 (48-58) 0 (48-58) 0 (48-58) 25% 0% 25% 25% 50% 25% 25% 25% 25% 0% 0% 50% 25% 25% 25% 25% 25% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% L.M.Ko 67% 33% 1 (12-32) 33% 1 (12-32) 33% 1 (12-32) 33% 1 (12-32) 1 (12-32) 1 (12-32) 1 (12-32) 1 (12-32) 33% 33% 43% 14% 14% 29% 1 (26-45) 2 (18-25) 3 (10-17) 1 (26-45) 14% 29% 43% 14% 1 (26-45) 2 (18-25) 14% 29% 1 (26-45) 1 (26-45) 1 (26-45) 14% 14% 14% 1 (26-45) 14% 1 (26-45) 14% 1 (26-45) 14% 1 (26-45) 14% 1 (26-45) 14% 1 (26-45) 14% 100% 100% 67% 100% 100% 100% 100% 67% 100% 100% 67% 100% 67% 100% 100% 67% 67% 33% 67% 33% 67% 67% 67% 100% 67% 100% 100% 67% 67% 33% 67% 67% 100% 33% 1 (35-46) 2 (17-34) 3 (1-16) 2 (17-34) 1 (35-46) 2 (17-34) 1 (35-46) 33% 67% 100% 67% 33% 67% 33% 2 (18-27) 25% 2 (18-27) 1 (28-42) 1 (28-42) 25% 13% 13% 1 (28-42) 3 (11-17) 2 (18-27) 13% 38% 25% 1 (28-42) 13% 1 (28-42) 1 (28-42) 1 (28-42) 1 (28-42) 13% 13% 13% 13% 1 (28-42) 1 (28-42) 13% 13% 33% 33% 33% 1 (28-42) 13% 1 (28-42) 13% 1 (28-42) 13% Referenced % 3 (10-17) 1 (26-45) 1 (26-45) 2 (18-25) 3 (1-16) 3 (1-16) 2 (17-34) 3 (1-16) 3 (1-16) 3 (1-16) 3 (1-16) 2 (17-34) 3 (1-16) 3 (1-16) 2 (17-34) 3 (1-16) 2 (17-34) 3 (1-16) 3 (1-16) 2 (17-34) 2 (17-34) 1 (35-46) 2 (17-34) 1 (35-46) 2 (17-34) 2 (17-34) 2 (17-34) 3 (1-16) 2 (17-34) 3 (1-16) 3 (1-16) 2 (17-34) 2 (17-34) 1 (35-46) 2 (17-34) 2 (17-34) 3 (1-16) 1 (35-46) 6 (1-2) 4 (7-10) 5 (3-6) 3 (11-17) 3 (11-17) 5 (3-6) 5 (3-6) 5 (3-6) 1 (28-42) 4 (7-10) 6 (1-2) 3 (11-17) 2 (18-27) 4 (7-10) 3 (11-17) 1 (28-42) 2 (18-27) 2 (18-27) 2 (18-27) 4 (7-10) 3 (11-17) 2 (18-27) 2 (18-27) 3 (11-17) 2 (18-27) Referenced % 2 (10-11) 1 (12-32) 75% 50% 63% 38% 38% 63% 63% 63% 13% 50% 75% 38% 25% 50% 38% 13% 25% 25% 25% 50% 38% 25% 25% 38% 25% 71% 57% 57% 71% 43% 57% 29% 71% 57% 43% 29% 57% 43% 14% 14% 57% 43% 43% 29% 43% 29% 29% 14% 14% 14% 14% 2001-2005 (N=3) Referenced Frequency (rank) 33% 33% 33% 33% 33% 100% 100% 33% 67% 33% 100% Referenced Frequency (rank) 1 (12-32) 1 (12-32) 1 (12-32) 1 (12-32) 1 (12-32) 3 (1-9) 3 (1-9) 1 (12-32) 2 (10-11) 1 (12-32) 3 (1-9) 5 (1-3) 4 (4-9) 4 (4-9) 5 (1-3) 3 (10-17) 4 (4-9) 2 (18-25) 5 (1-3) 4 (4-9) 3 (10-17) 2 (18-25) 4 (4-9) 3 (10-17) 1 (26-45) 1 (26-45) 4 (4-9) 3 (10-17) 3 (10-17) 2 (18-25) 3 (10-17) 2 (18-25) 2 (18-25) 1 (26-45) 1 (26-45) 1 (26-45) 1 (26-45) 1996-2000 (N=3) Referenced % 100% 100% 100% 33% 100% 33% 100% 33% 100% 33% Referenced Frequency (rank) 3 (1-9) 3 (1-9) 3 (1-9) 1 (12-32) 3 (1-9) 1 (12-32) 3 (1-9) 1 (12-32) 3 (1-9) 1 (12-32) 1991-1995 (N=8) Referenced % Communication Facility Management Sports-Related Theory and Foundations Budgeting First Aid and Safety Prevention Human Resource Management Legal Aspects Marketing Administrative Skills Public Relations Financial Management Information Technology Accounting Event Management Self Management Decision Making Employee Relations/Labour Relations Management Techniques Programming Techniques Writing Skills Customer Relationship Management Evaluation skills Research in Sports Fund Raising and Sponsorship Governance Goal Setting Leadership Coaching Economics Problem Solving Public Speaking Purchasing Risk Management Field Experience in Sports Management Planning Resource Management Service Provision and Development Crisis response Coordinating Mass Communication/Mass Media Staff Meetings Ethics in Sports Management Language Management Theory Personal Fitness Sports Practice Foresight Human Relations Implement Negotiation Skills Organising Supervision Skills Conflict Resolution Controlling and Monitoring Personal Attributes Political Awareness Stock Management Referenced % Competency 1986-1990 (N=7) Referenced Frequency (rank) 1 (19) 2 (17) 3 (16) 4-8 (15) 4-8 (15) 4-8 (15) 4-8 (15) 4-8 (15) 9-10 (13) 9-10 (13) 11-12 (12) 11-12 (12) 13-15 (11) 13-15 (11) 13-15 (11) 16-20 (10) 16-20 (10) 16-20 (10) 16-20 (10) 16-20 (10) 21-23 (9) 21-23 (9) 21-23 (9) 24-25 (8) 24-25 (8) 26-27 (7) 26-27 (7) 28-33 (6) 28-33 (6) 28-33 (6) 28-33 (6) 28-33 (6) 28-33 (6) 34-37 (5) 34-37 (5) 34-37 (5) 34-37 (5) 38-41 (4) 38-41 (4) 38-41 (4) 38-41 (4) 42-46 (3) 42-46 (3) 42-46 (3) 42-46 (3) 42-46 (3) 47-52 (2) 47-52 (2) 47-52 (2) 47-52 (2) 47-52 (2) 47-52 (2) 53-58 (1) 53-58 (1) 53-58 (1) 53-58 (1) 53-58 (1) 1980-1985 (N=3) Referenced Frequency (rank) 1980-2005 Rank / Referenced Frequency Table 8: Summary of Critical Competences by Year 2 (7-24) 3 (1-6) 2 (7-24) 3 (1-6) 3 (1-6) 2 (7-24) 2 (7-24) 2 (7-24) 2 (7-24) 2 (7-24) 2 (7-24) 2 (7-24) 3 (1-6) 2 (7-24) 3 (1-6) 2 (7-24) 2 (7-24) 1 (25-41) 1 (25-41) 1 (25-41) 67% 100% 67% 100% 100% 67% 67% 67% 67% 67% 67% 67% 100% 67% 100% 67% 67% 33% 33% 33% 2 (7-24) 1 (25-41) 1 (25-41) 1 (25-41) 2 (7-24) 2 (7-24) 67% 33% 33% 33% 67% 67% 1 (25-41) 2 (7-24) 1 (25-41) 3 (1-6) 2 (7-24) 33% 67% 33% 100% 67% 2 (7-24) 1 (25-41) 1 (25-41) 67% 33% 33% 1 (25-41) 33% 1 (25-41) 33% 1 (35-46) 1 (35-46) 1 (35-46) 33% 33% 33% 1 (25-41) 1 (25-41) 33% 33% 1 (35-46) 1 (35-46) 33% 33% 1 (25-41) 33% 1 (25-41) 33% 1 (25-41) 33% L.M.Ko 53-58 (1) Training and Educating 1 (12-32) 33%