A reliability-driven placement procedure based on thermal force model

advertisement

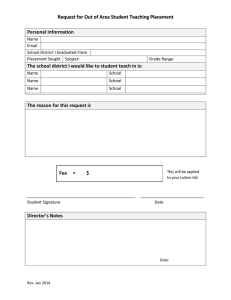

A reliability-driven placement procedure based on thermal force model Jing Lee Department of Electronic Engineering Southern Taiwan University of Technology 1 Nan-Tai St, Yung-Kang City, Tainan Hsien, Taiwan 710, R.O.C. Email: leejing@mail.stut.edu.tw Abstract This paper deals with placing chips on an MCM module in chip array style for minimizing the system failure rate. The placement procedure begins with constructing an initial placement based on cooling considerations. Then, a thermal force model is presented to transform the reliability-driven placement problem to solve a set of simultaneous nonlinear equations to determine thermal-force-equilibrium locations of the chips. A modified Newton-Raphson method is used to solve this system of equations. Finally, a chip assignment procedure transforms the thermal-force-equilibrium placement into an array style placement for minimum thermal distortion. Two assignment methods are developed and compared each other. Experiments on three industrial MCMs designed by IBM show that the obtained placements have significant improvements to their original designs in system reliability. Additionally, a simulated annealing approach is presented for justifying the performance of the proposed method. Index Terms—Force-directed placement, reliability, thermal force, thermal placement. 1. Introduction A Multi-Chip Module (MCM) considered in this paper is described as a package combining multiple chips into a single system-level unit. The resulting module is capable of handing an entire function. MCMs provide a very high level of system integration, with hundreds of bare chips that can be placed very close to each other on a substrate. Therefore, systems based on MCM architectures can achieve much denser circuits and much shorter 1 interconnect distances among the chips than those in which chips are packaged in a single chip module and placed on PCBs. However, this denser integration results in higher heat flux densities at the substrate and creates a very challenging thermal management problem. For example, the IBM’s S/390 Servers that have 35 chips mounted on a 12.7cm × 12.7cm substrate dissipate 1274 W per module [1]. If the dissipated heat is not properly removed, higher operating temperatures can occur. A higher temperature not only affects circuit performance directly by slowing down the transistors on chips, but also decreases their reliability. As a result, supporting high heat fluxes while maintaining relatively low chip temperatures is one of the major challenges facing today’s MCM system designers [2], [3]. The MCM placement problem is to assign the exact locations of chips on a substrate subject to timing, thermal, and routability constraints [4], [5]. Most of the previous placement methods used for MCM are extensions of well-known methods from the VLSI domain or the PCB area [6], [7], which are mainly focused on routability. However, temperature distribution on an MCM substrate is the most important reliability factor. It is conceivable that a placement tool without thermal considerations could place some chips with high heat dissipation closely spaced together. This would result in hot spots on the substrate, even though the total power consumption is constrained. To overcome the problem of overheating it is essential to develop good chip placement techniques for optimizing the system reliability, which is usually referred as the thermal placement problem. There are mainly two types of chip placements related to the MCM design, namely, full custom style and chip array style. In the full custom style placement, the active substrate is treated as a continuous plane on which chips of varying sizes and shapes are free to reside anywhere on the active substrate as shown in figure 1(a). On the other hand, in the chip array style placement, the active substrate is partitioned into a matrix of identical chip sites into which the chips are placed as shown in figure 1(b). Noticed that the pitch (i.e. center-to-center 2 spacing) of the chip sites in x-direction can be different from the pitch in y-direction. Chips px py Su bst rat e Substrate C h i p sC h i p s i t eAs c t i v e substrate Active substrate (a) Full custom style Fig. 1. (b) Chip array style Two types of MCM placements. Basically, placements of different styles need different placement algorithms. Previous studies on the thermal placement problem of MCM thus fall into two major categories: iterative-based approaches for chip array style placements and force-directed algorithms for full custom style placements. The iterative-based approaches consist of simulated annealing approaches [8]-[10] and hybrid genetic algorithms [11], [12]. Force-directed algorithms include the fuzzy-force [13] and the thermal-force [14] algorithms. In the study, an extension of the previous thermal-force algorithm in [14] is developed to cover the chip array style thermal placement problem. This method generates excellent solutions both effectively and efficiently. Another important merit is that the proposed thermal force model is easily combined with other force models developed for the objects of routability and performance [15]-[18]. So, a multiobjective optimal placement problem can be modeled by a hybrid force model that is a combination of different force models, and solved by the same technique presented in the paper. In addition, a simulated annealing approach is also presented for justifying the performance of the proposed method. The rest of this paper is organized as follows: some preliminary knowledge, such as 3 problem description, reliability evaluation, packaging structure, and temperature calculation are provided in Section 2. The thermal placement algorithm based on a modified thermal force model is presented in Section 3. Simulated annealing approach is presented in Section 4. Examples with computational results are given in Section 5. Conclusions are drawn in Section 6. 2. Preliminaries 2.1 Problem description The chip array style thermal placement problem can be stated briefly as follows: given a set of chips C ci 1 i m with its set of heat dissipations Q qi 1 i m and a set of chip sites S s j 1 j n, n m on a two-dimensional substrate as shown in figure 1(b), assign each chip to one of the chip site such that the system failure rate is minimized. For most practical cases, some chips may have been pre-assigned to some chip sites for timing or cooling considerations. These chips are called fixed chips; the others are called movable chips. Both types of chips are considered in the study. 2.2 Reliability evaluation It is well known that most of the physical and chemical processes that can cause component failure are usually accelerated at elevated temperatures [19]. In addition, the unevenly distributed power dissipation of chips on a substrate may result in hot spots, which can induce thermal stresses. When the stresses are severe enough and/or go through enough cycles, they can cause chip failure, usually by rupturing of the solder joints [20]. Hence, temperature is generally considered as a key parameter in failure mechanisms. An Arrhenius relation has generally been adopted to model the strong dependency of failure rate with temperature, E 1 1 (Ti ) (Tr ) exp a k Tr 4 Ti (1) where (Ti) and (Tr) are the failure rates of an individual chip at a temperature of Ti K and at a reference temperature of Tr K, respectively; Ea is the activation energy (eV); k is the Boltzmann's constant. Obviously, to determine the failure rate of an individual chip, various operating parameters need to be specified. Without loss of generality, in this paper, all chips are assumed to have the same factors of (Tr) and Ea, which are 1 Fit (i.e. 10-9/hour) and 1 eV, respectively. The objective is to minimize the system failure rate of an MCM, S, which is given by the sum of the individual chip failure rates given in (1). m S Ti (2) i 1 2.3 Package structure and temperature evaluation In order to estimate S, one has to know the temperature distributions of chips on the substrate. Since package structure and cooling conditions directly influence the temperature distributions, they must be determined firstly. However, a practical package structure usually is not completely determined at the placement stage, and a practical structure also is too complex to calculate the temperature profiles. So, a simplified package model, as illustrated in figure 2, is presented for reducing the computation time of calculating the temperature profiles. The package consists of a sandwich structure formed from the ceramic multiplayer substrate-epoxy adhesive-aluminum heat sink with thicknesses of 3.75 mm, 0.076 mm, and 1.27 mm, respectively. Within each layer, the material is assumed to be linear, isotropic, and homogeneous. Temperature and heat flow are continuous at interfaces between layers. Thermal conductivities of the multilayer substrate, the epoxy layer, and the heat sink are 39.4 W/mK, 0.276 W/mK, and 195 W/mK, respectively. Chips are treated as heat fluxes directly from the substrate. Heat loss from the package into the board and from the finned side is quantified by heat transfer coefficients, htop and hbot. Air conduction or convection within the 5 space between the MCM ceramic surface and the cover is neglected (the worst case effect on results). Adiabatic heat flux is used as a boundary condition at the substrate edges. The TAMS (Thermal Analyzer for Multilayer Structures) program developed by Ellison is used to calculate the temperature distributions of chips on the substrate. This computer program can predict the steady-state temperature in four-layer-rectangular structures with anisotropic conductivity, lumped thermal resistances, and planar-discrete sources [21]. htop Epoxy Heat sink Multilayer substrate h bot Fig. 2. Package model. 3. Thermal force placement algorithm The complete placement approach, named Thermal Force Placement (TFP) algorithm, consists of three phases: generating a ‘good’ initial placement in phase 1, solving the system of thermal force equations for obtaining a thermal-force-equilibrium (TFE) placement in phase 2, and transforming the TFE placement to a chip array style placement in phase 3. 3.1 Initial placement Since a good initial placement usually can speed up the entire placement procedure and generates a better final placement, it is desirable to construct a better initial placement. In general, a good placement for reliability can be constructed by the following two rules: Rule I. High power chips are preferred to be placed around the border of the substrate. Rule II. Avoid placing high power chips on neighboring chip sites. Rule I is based on the fact that chip sites at the border of a substrate have larger cooling 6 area than those in the inner region, since a real substrate always has a larger area than an active substrate. Rule II is used to avoid hot spots that are usually generated by placing high power chips closely to each other. A simple and effective initial placement algorithm based on the above two rules is provided below. Here, the configuration of chip sites is considered as a series of concentric rectangular rings with a core. The initial placement algorithm begins with sorting the chips in descendent order of their heat dissipations. That is qi qi 1 for i = 1 to m-1. Then, for satisfying Rule I, chips are assigned into chip sites from the outer ring to the inner ring. During the procedure of ring assignment, every rectangular ring is further partitioned into four arrays of chip sites. As an example, figure 3(a) shows a ring structure of a 6 6 matrix of chip sites. The chip sites in the outer ring are partitioned into four arrays, S L sL,i 1 i 5, S B sB,i 1 i 5, S R sR,i 1 i 5 , and ST sT ,i 1 i 5. After that, for satisfying Rule II, chips are assigned into the four arrays one by one in a rotation order of SL, SR, ST, SB, SL, SR, ST, SB, and so forth. For the chip assignment in an array, chips are assigned into chip sites on an alternate order. In the case of figure 3(a), the chip assignment order in the rectangular ring is sL,1, sR,1, sT,1, sB,1, sL,3, sR,3, sT,3, sB,3, sL,5, sR,5, sT,5, sB,5, sL,2, sR,2, sT,2, sB,2, sL,4, sR,4, sT,4, sB,4. As a result, chip placement in Ring II is as depicted in figure 3(b). For easily programming, all chips are assumed to be movable and all chip sites are unoccupied at the beginning. If there are some fixed chips in the practical problem, the fixed chip and the chip occupying the chip cite which is pre-assigned to the fixed chip have to swap their positions after the above procedure. 7 Ring II Ring I Core sL,1 sT ,5 sT ,4 sT ,3 sT ,2 sT ,1 C1 sL,2 sR,5 C 13 C10 sL,3 sR,4 C5 C18 sL,4 sR,3 C17 C6 sL,5 sR,2 C9 C14 sR,1 C4 sB,1 sB,2 sB,3 sB,4 sB,5 (a) Configuration of chip sites Fig. 3. C11 C16 C19 C8 C7 C15 C20 C12 C3 C2 (b) Chips placement in Ring II Initial placement. 3.2 Thermal-force-equilibrium placement Thermal force model was first presented by the author for the thermal placement of the full custom design style [14]. It is based on the observation that heat loss conducted from the substrate edges is insignificant when compared to the heat loss flow from the top and bottom sides of the substrate. Therefore, a rectangular substrate of several heat sources can be transformed into an unbounded substrate containing an infinite number of mirror image heat sources as shown in figure 4. The unbounded substrate has the same thermophysical properties as the original bounded substrate [22] [23]. The mirror image substrate at the rth row and the cth column is called the r-c-substrate. The chips on the r-c-substrate are denoted by the superscript of (r, c). In the situation of unbounded substrate, the temperature rise of a considered chip is results from two sources: the heat generated by itself and that conducted from other chips (including the image heat sources). The heat conducted from other chips is analogy as repulsion forces to push the considered chip in the thermal force model. If the considered chip can freely move on the substrate, it will move far away from these chips to the force 8 equilibrium position and the considered chip can be expected at a lower chip temperature since the temperature rise caused by other chips is reduced by enlarging the distances between them. While the heat flux decreases with the square of the distance from the heat source in an infinite body, it is reasonable to formulate the thermal force exerts on ci by c jr,c as f ij( r,c ) 0, if ci is fixed or c (jr,c ) ci qj , otherwise ( r,c ) 2 ( r,c ) 2 (x ) ( y ) ij ij (3) ) ) where xij( r,c) x (jr,c) xi , yij( r,c) y (jr,c) yi , and ( x (r,c , y (r,c ) denotes the coordinates of j j ) . The location of cj in the real substrate is simply denoted as (xj, yj). c (r,c j Y Mirror image heat sources 2-2-substrate Row 2 qi qj qj q i qi qj qj q i qi 1 qi q j qj qi qi q j qj qi qi q j 0 qi qj q i qi qj q i qi -1 qi q j qj qi qi q j qj qi qi q j -2 qi qj q i qi qj q i qi Column -2 qj qj -1 0 qj qj 1 qj qj X qj 2 Real substrate Fig. 4. Replace insulated boundaries by mirror image sources For most actual MCMs, the chip pitches in x- and y- directions may be unequal. This implies that the same magnitude of thermal-forces exerted on a chip in different directions might have different pushing effects. Thus, the thermal-force model must be modified as 9 f ij( r,c ) 0, if ci is fixed or c (jr,c ) ci qj otherwise ( x ( r,c ) ) 2 (y ( r,c ) ) 2 , ij ij (4) where p y /p x , px and py are the pitches in x- and y-direction, respectively. Expanding (4) to cover all m chips, one obtains the net thermal force on ci to be m ( 0 ,0 ) a ( a,c) (a,c) a 1 Fi f ij f ij f ij( r,a) f ij(r,a) f ij a 1 r a 1 c a j 1 (5) Theoretically, the maximum value of a is infinity. However, since f ij(r,c) is an inverse 2 measure of rij(r,c) , setting the maximum value of a to five is adequate [14]. In the phase, a system of thermal-force equations based on the initial placement is constructed as equation (5). By setting Fi = 0, and solving the system of equations by a modified Newton-Raphson method [14] to get the TFE positions of ci, for 1 i m , the obtained placement is called a thermal-force-equilibrium (TFE) placement. For properly defining a convergent solution, set Norm 1 2m 2 F m i,x Fi,y (6) i 1 The stopping criterion is set to be Norm < 0.0001 according to the experimental results. To justify the effect of introducing into the thermal force model, figures 5(a) and (b) show two TFE placements for a 30-chip-site module with 1 (i.e. without the consideration of the unequal pitch effect) and p y /p x (i.e. with the consideration of the unequal pitch effect), respectively. In the example twenty-nine chips with different powers are placed on a substrate of 6×5 chip sites. Obviously, both TFE placements have the desirable feature of placing chips apart to abound with the substrate, because the chips are mutual excluded in the 10 thermal force model. This feature is important since it reduces the difficulty of the chip assignment procedure. In addition, the TFE placement in figure 5(b) is more close to a 6×5 matrix than the one in figure 5(a). So, introducing into the thermal-force model is helpful for generating an array style placement. More data listed in Tables 1 about the example will be further described in Section 5. (b) p y /p x (a) 1 Fig. 5. TFE placements with power distributions (W) of a 30-chip-cite module. 3.3 Chip assignment Since a TFE placement is not usually an exact array style, a sequence of chip assignment procedures, thus, is needed to transform the TFE placement to an array style placement with minimum distortion to the thermal field. In the paper, two different assignment techniques, Linear Assignment (LA) and Thermal Assignment (TA) are proposed and compared each other. 3.3.1 Linear assignment Let aij be a Boolean variable describing the assignment of chip ci to chip site sj 1, if assign ci to s j aij 0, if not 11 (7) Each chip must be placed, and at any chip site only one chip can be assigned. Therefore m a 1 for j = 1, 2, …, n (8) 1 for i = 1, 2, …, m (9) ij i 1 n a j 1 ij The objective in the linear assignment is to m minimize n a d i 1 j 1 ij (10) ij where dij is the distance between ci and sj. This linear assignment problem can be solved by the Hungarian method due to Kuhn [24]. As an example, figure 6 shows the final placement which is transformed from figure 5(b) by the linear assignment. A weakness of the linear assignment is that it does not correspond to the fact that moving a hotter chip would produce larger thermal distortion than moving a cooler chip in the TFE field. In addition, it needs a m n memory space for storing dij. For huge problems, the space needed for this might prevent us from using this method. Fig. 6 101 (30) 102 (25) 103 (30) 97.7 (27) 101 (30) 105 (30) 91.2 (16) 91.6 (13) 89.4 (16) 103 (30) 101 (30) 90.2 (16) 88.0 (16) 84.8 (7) 87.1 (16) 103 (25) 90.1 (16) 107 (30) 104 (25) 100 (30) 91.4 (16) 93.6 (13) 93.9 (16) 107 (30) 100 (30) 98.1 (27) 104 (30) 103 (25) 102 (30) Final placements with chip power (in parenthesis, W) and temperature (oC) distributions of the 30-chip-cite module after linear assignment. 3.3.2 Thermal assignment 12 Thermal assignment is developed for taking the chip power’s effect into account. It consists of three steps: fixed, rebalance, and assignment. In the fixed step, if only one chip locates in a chip site in the TFE placement, the chip is assigned and fixed at the chip site; if more than one chip locates at the same chip site, the one with the largest heat power is assigned and fixed at the chip site. Next, for the unfixed chips, the system of the thermal-force equations are reconstructed and resolved to obtain their new TFE positions. After that, each unfixed chip is assigned into the nearest vacant chip site to finish a complete placement. Figure 7 shows the final placement which is transformed from figure 5(b) by the thermal assignment. Observing the case of the 7-W chip and the 16-W chips located at the same chip site in figure 5(b), the 16-W chip will occupy the chip site after executing thermal assignment, but it is not always the case after executing linear assignment. So, thermal assignment could be expected to generate better final placement than linear assignment due to produce less thermal distortion in the chip assignment procedure. Experimental evidences are provided in Section 5. Another important merit is no extra memory space needed for the thermal assignment. Fig. 7 101 (30) 103 (25) 104 (30) 98.7 (27) 102 (30) 106 (30) 91.5 (16) 92.7 (13) 91.9 (16) 105 (30) 101 (30) 90.5 (16) 89.6 (16) 91.5 (16) 101 (25) 103 (25) 90.7 (16) 106 (30) 82.2 (7) 100 (30) 91.4 (16) 93.5 (13) 92.6 (16) 102 (30) 100 (30) 98.0 (27) 104 (30) 103 (25) 100 (30) Final placements with chip power (in parenthesis, W) and temperature (oC) distributions of the 30-chip-cite module after thermal assignment. 13 4. Simulated annealing approach Simulated annealing (SA) is a general purpose combinatorial optimization technique that is analogous to the process of metallurgical annealing in which a system is heated and then cooled gradually until the material achieves certain desired metallurgical properties [25]. It has been shown to produce good quality placements for routability [26], [27]. So, a simulated annealing approach also proposed here for comparing and justifying the TFP algorithm. 4.1 Concept of SA In general, SA starts with randomly generating an initial array style placement P and by initializing the so-called temperature parameter T. Then, at each iteration a candidate placement P’ is found by randomly selecting two chips of unequal heat dissipations in current placement and then interchanging their positions. Whether P’ is accepted as new placement depending on S (P), S (P’) and T. P’ replaces P if S (P’) < S (P) or, in case S (P’) S (P), with a probability which is a function of T and = S (P’) - S (P). The probability is generally computed following the Botzmann distribution e / T . At the beginning, T is set to a very high value such that most of the candidate placements are accepted. Then T is gradually decreased, so the candidates with higher failure rates than the current placement have less chance of being accepted. Finally, T is reduced to a very low value so that only the candidates with lower system failure rate than the current placement are accepted, and the algorithm converges to a placement of a low system failure rate. The procedure of SA is shown in figure 8. 4.2 Initial temperature The initial temperature must be chosen so that almost all candidate solutions are accepted initially. That is, the initial accepted rate 0 must be close to unity. Here we use the method developed by [28] to determine the initial temperature T0. In his method, T0 is 14 determined using the average changes of cost function after randomly adjusting trial solution several times, the formula is as follow: 0 e av / T (11) where av is the average changes of . From Eq. (11), we get T0 av l n ( 01 ) (12) procedure SA( ) T ← T0 // initial temperature P← random initial placement S (P) ← TAMS(P) // calculate the temperature distributions and S of P // by TAMS package while (T > Tf) // Tf is the frozen temperature for i← 1 to M // M is the length of Markovian chain P’ ← PERTURB(P) // randomly interchanging two unequal chips S (P’) ←TAMS(P’) ←S (P’) - S (P) if < 0 or RANDOM(0,1) > e / T then P ← P’ ; S (P) ←S (P’) endif end T ← SCHEDULE(T) end OUTPUT(P) Fig. 8 Procedure of SA 4.3 Cooling schedule The choice of an appropriate cooling schedule is crucial for the performance of the simulated annealing algorithm. The cooling schedule defines the value of T at each iteration k, 15 Tk+1 = f(Tk, k). Theoretical results on non-homogeneous Markov chains [29] state that under particular conditions on the cooling schedule, the simulated annealing converges in probability to global optima for k ∞. The logarithmic law fulfils the hypothesis. However, it is too slow for practical applications. Instead, the geometric law: Tk+1 = α× Tk, is frequently used, where α is the cooling rate parameter which is determined experimentally. Kirkpatrick et al. [25] propose this rule first with α = 0.9. For saving runtime, the cooling schedule is usually divided into two or three stages. TimberWolf [27], the most widely used and successful placement package based on simulated annealing, suggests α = 0.8, 0.95, and 0.8 in the high, medium, and low temperature ranges, respectively. We tried several different cooling strategies for the tested problems, and the best one is a two-stage schedule. That is, α is taken 0.85 initially until the probability is smaller than 0.6, and then α is taken 0.95. 4.4 Length of Markov chain The length of Markovian chain, M, is the number of trials at each temperature. In general, the higher the number of M, the better the results obtained. However, the runtime increases rapidly. There is a recommended number of M as a function of the problem size m in [30]. We tried several different functions for M, and the experimental results show that M 2 m (13) is the best one. Setting M a value higher than Eq. (13) can not further improve the final solutions in our tested cases. 5. Examples and computational results The present algorithms have been implemented in C language, and run on a 2.8GHz Pentium IV personal computer. Three industry MCMs designed by IBM are used to test the proposed algorithms. 5.1 The benchmark MCMs 16 Table 1 summarizes some information about the benchmark MCMs. The 30-chip-site module and the 31-chip-site module are derived from IBM’s GEMI modules [31], [32]. The sizes of real substrate and active substrate of the 30-chip-site module are square measuring 127.5 mm and 111.85 mm on the side, respectively. The active substrate is divided into a 6×5 matrix of identical chip sites. Each chip site is a rectangle of 18.45 mm × 22.05 mm in size. Twenty-nine chips, with the chip sizes ranging from 12.9 mm to 17.4 mm on the side and power ranging from 7 W to 30 W, are placed on the substrate. The 31-chip-site module is very like the 30-chip-site module except for the first row that has six chip sites. Each chip site in the first row is square with an 18.45 mm edge. A large example, 121-chip-site module, is derived from IBM’s TCM with 110 chips [33]. The sizes of the substrate and the active substrate are square measuring 127.5 mm and 118.8 mm, respectively. The active substrate is divided into an 11×11 matrix of identical chip sites. Each chip and chip site are square with a 6.5 mm and a 10.8 mm edge, respectively. Power range of chips is from 8.9 W to 20 W. Table 1. MCM information Modules No. of Chip Px Py chips sites (mm) (mm) Power dissipation value (power × chip number) 30-chip-site 29 6×5 18.45 22.05 30W×12、27W×2、25W×4、16W×8、13W×2、 7W×1 31-chip-site 31 1×6 18.45 18.45 30W×14、27W×2、25W×4、16W×8、13W×2、 7W×1 18.45 22.05 5×5 121-chip-site 110 11×11 10.8 10.8 20W×17、19.5W×4、17.3W、16.9W×8、15W×2、 14.7W×1、14.3W×1、13.9W×1、13.8W×1、 13.6W×1、10.9W×1、10W×1、8.9W×71 For giving a fair comparison, all examples are treated as having the same package structure and cooling condition as depicted in figure 2. Because the average heat flux is very high in all examples, cooling conditions are selected for force convection at a velocity of 2.5 17 m/s for the top side, and jet impingement at a velocity of 0.5 m/s for the bottom side. Correspondingly, htop and hbot are 43.8 W/m2 K and 832 W/m2 K, respectively. 5.2 Comparisons between TA and LA Thermal performances, S, and runtimes of the tested examples are summarized in Table 2, where Tav, TSD , Tmax, Tmin, and T are the mean, standard variation, maximum value, minimum value, and range of chip temperatures, respectively. As expected, S in TA are lower from 0.7% to 3.4% than S in LA. Thus, TA is superior to LA. Table 2. Comparisons between TA and LA. MCM Algorithm Tav(oC) TSD Tmax Tmin T S (Fit) Runtime (s) TA 97.8 6.1 106 82 24 6.90 10 4 15.5 LA 97.7 6.4 107 85 22 6.95 10 4 15.3 TA 102.8 6.6 112 88 24 11.4 10 4 21.4 LA 102.6 8.2 115 86 29 11.8 10 4 21.2 TA 161.0 10.3 184 149 35 2.75 10 7 1407 LA 160.9 11.1 187 148 39 2.81 10 7 1413 30-chip-site 31-chip-site 121-chip-site 5.3 Comparisons between TFP and IBM The results obtained by IBM, TFP algorithm, and SA approach are compared in Table 3. The chip placements in IBM are obtained from [32], [33], but the temperature distributions are analyzed under the present package structure and cooling conditions. The results show that placements obtained by TFP algorithm have significant reliability improvement over the original placements by IBM. The ratios of S in TFP to S in IBM are 88.5%, 94.2%, and 22.0%, respectively to the 30-chip-site module, the 31-chip-site module, and the 121-chip-site module. 18 Table 3. Comparisons among IBM, TFP, and SA MCM 30-chip-site 31-chip-site 121-chip-site Algorithm Tav(oC) TSD Tmax Tmin T S (Fit) Runtime (s) IBM 98.4 8.1 108 80 28 7.8 10 4 N.A. TFP 97.8 6.1 106 82 24 6.9 10 4 15.5 SA 97.4 6.2 104 85 19 6.7 10 4 4390 IBM 103 7.9 115 88 27 12.1104 N.A. TFP 102.8 6.6 112 88 24 11.4 10 4 21.4 SA 102.7 6.2 110 91 19 11.0 10 4 6450 IBM 158.9 31.6 228 124 104 12.5 107 N.A. TFP 161.0 10.3 184 149 35 2.75 10 7 1407 SA 160.6 9.3 181 151 30 2.6 10 7 195963 Algorithm Tmax Tmin Tdif S (Fit) Runtime (s) IBM 108 80 28 7.8 10 4 -. 29 chips TFP 106 82 24 6.9 10 4 15.5 (1999) SA 104 85 19 6.7 10 4 4390 IBM 115 88 27 12.1104 -. 31 chips TFP 112 88 24 11.4 10 4 21.4 (1999) SA 110 91 19 11.0 10 4 6450 IBM 228 124 104 12.5 107 - 121 chips TFP 184 149 35 2.75 10 7 1407 (1992) SA 181 151 30 2.6 10 7 195963 MCM 19 For further comparisons, the chip placements with powers and temperature distributions of the 121-chip-site module obtained by IBM and TFP algorithm are shown in figures 9(a) and (b), respectively. In figure 9(a), all the high power chips are placed in the central region of the substrate, and the low power chips are placed at the border of the substrate. So, the temperature profile at central region is much hotter than at border of the substrate. The value of T is up to 104 oC. By contrast, in figure 9(b), most high power chips are placed around the border of the substrate, and most low power chips are placed in the central region of the substrate. So, the temperatures distribution on the substrate shown in figure 9(b) is more uniform than those in figure 9(a). T in figure 9(b) is only 35 oC. 5.4 Comparisons between TFP and SA In Table 3, one can see that S obtained by TFP algorithm are only 3.0%, 3.6%, and 5.8% higher than those obtained by SA approach corresponding to 30-chip-site, 31-chip-site, and 121-chip-site modules. However, the runtimes in TFP are only a fraction of the runtimes in SA. Note that SA needs to calculate the temperature distributions and S for every candidate placement so as to justify whether the candidate placement can be accepted or not. However, calculating the temperature distributions on the substrate is very time consuming since it has to solve a three dimensional partial differential equation. Virtually, all iterative-based approaches suffer the same difficulty. These methods, therefore, are generally unsuitable for even middle-sized thermal placement problems. By contrast, the TFP algorithm calculates temperature distributions and S only when the final placement has been determined. So, it can be applied for large-sized thermal placement problems more effectively. 20 128 134 137 138 135 (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) 135 138 137 133 127 (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) 174 154 1 5 2 1 7 8 176 ( 2 0 ) ( 1 0 ) ( 8 . 9 () 1 9 . 5()2 0 ) 134 142 148 150 148 (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) 148 150 148 141 133 (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) 173 153 154 165 ( 1 9 . 5( )8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 1 3 . 9 ) 138 149 173 166 168 170 (8.9) (8.9) (16.9) (8.9) (8.9) (10) 168 165 173 148 137 (8.9) (8.9) (16.9) (8.9) (8.9) 141 152 (8.9) (8.9) 213 (20) 204 (20) 141 158 192 218 (8.9) (8.9) (16.9) (20) 213 (20) 215 (20) 204 (20) 151 140 (8.9) (8.9) 175 (20) 135 149 (8.9) (8.9) 216 (20) 205 (20) 217 (20) 208 (20) 124 131 136 139 139 (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) 151 152 151 152 152 153 155 166 ( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 1 4 . 3 ) 1 7 9 1 5 8 1 5 4 1 5 2 1 5 1 1 5 2 1 5 3 1 5 7 1 7 9 180 ( 1 6 . 9( )8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 () 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 () 1 6 . 9()2 0 ) 210 187 156 139 (20) (16.9) (8.9) (8.9) 184 176 158 154 152 152 152 153 156 174 ( 2 0 ) ( 1 4 . 7( )8 . 9 () 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 () 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 () 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 1 6 . 9 ) 184 1 6 1 1 5 6 1 5 4 1 5 4 1 5 3 1 5 3 1 5 3 1 5 4 1 5 5 169 ( 2 0 ) ( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 () 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 2 0 ) 148 138 (8.9) (8.9) 144 172 167 174 194 170 159 168 145 136 (8.9) (16.9) (8.9) (8.9) (17.3) (8.9) (8.9) (16.9) (8.9) (8.9) 128 139 147 152 156 169 154 (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) (14.7) (8.9) 153 157 159 ( 8 . 9 () 8 . 9 )( 1 0 . 9 ) 177 156 153 151 151 152 153 156 161 179 181 ( 2 0 )( 1 6 . 9( )8 . 9 () 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 () 8 . 9 () 2 0 ) 171 185 220 228 216 227 218 190 171 (15) (10.9) (19.5) (19.5) (13.6) (19.5) (19.5) (13.8) (15) 227 214 222 (20) (13.9) (20) 175 167 ( 1 5 )( 1 6 . 9 ) 149 151 153 151 154 155 152 153 156 174 ( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 () 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 1 9 . 5 ) 226 215 226 217 192 157 140 (20) (14.3) (20) (20) (16.9) (8.9) (8.9) 139 157 191 218 (8.9) (8.9) (16.9) (20) 1 5 5 1 7 2 176 180 179 ( 2 0 ) ( 2 0 ) ( 8 . 9 )( 1 6 . 9()2 0 ) 1 5 6 1 5 6 1 5 5 1 5 6 1 5 7 1 5 7 1 5 5 155 153 150 ( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 () 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 ) 150 146 140 131 (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) 1 6 4 1 5 6 1 5 3 1 5 9 1 7 8 171 159 167 156 153 166 ( 1 3 . 6( )8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 () 1 6 . 9()1 5 ) ( 8 . 9()1 3 . 8( )8 . 9 )( 8 . 9 () 1 7 . 3 ) 168 175 ( 2 0 )( 1 6 . 9 ) 139 138 136 131 125 (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) (8.9) (a) Placement by IBM 178 180 (20)(20) 1 7 5 152 171 176 156 ( 2 0 ) ( 8 . 9 () 1 9 . 5()8 . 9 () 2 0 ) (b) Placement by TFP algorithm Fig. 9 Placements with chip power (in parenthesis, W) and temperature (oC) distributions. 5.5 Relationship between thermal performances and system reliability It seems reasonable that a placement with higher average temperature also has higher system failure rate. However, the present study shows that the conclusion is not true. It is interesting to see that for the 121-chip-site module, the S in TFP is only 22 % of the S in IBM, but the Tav in TFP is 2.1 oC higher than the Tav in IBM. So, Tav is not a good measure for S. Note that as the decrease of one chip’s temperature always causes the increase of another chip’s temperature during the position interchange in a placement, so the value of Tav is not significantly different with different placements. Instead, reliability-better placements always have lower value of T due to these placements of lower Tmax and higher Tmin. This conclusion is very important since it means that a reliability-optimization placement problem can be simplified as a uniform-temperature-distribution placement problem. 6. Conclusion This paper deals with placing chips in array style on an MCM substrate to minimize the system failure rate. A TFP algorithm and a simulated annealing approach are presented for this problem. Three industrial MCMs designed by IBM are examined by the proposed 21 methods. The TFP algorithm generates excellent solutions both effectively and efficiently when comparing to the simulated annealing approach and IBM designs. Since, thermal placement problem is a NP-hard combinatorial optimization problem, it is very important to efficiently obtain ‘good’ solutions especially for huge problems. The TFP algorithm may be the best method when considering both effectiveness and efficiency. In addition, by combining the proposed force model with other force models developed for the objects of routability and performance, a multiobjective optimal placement problem can be solved by the same technique presented in this paper. Acknowledgments This work was supported by the National Science Council, Republic of China under contract no. NSC91-2215-E-218-005. I am pleased to thank Professor Jung-Hua Chou for his valuable comments and suggestions concerning this paper. References [1] Katopis GA. The evolution of ceramic packages for S/390 servers. Proc. of the Pacific Rim/ASME Intern Electron Packag; 2001. p. 13-20. [2] Kam T, Rawat S, Kirkpatrick D, Roy R, Spirakis GS, Sherwani N. EDA challenges facing future microprocessor design. IEEE Trans on Computer-Aided Des 2000; 19(12): 1498-506. [3] Garimella SV, Joshi YK, Bar-Cohen A, Mahajan R, Toh KC, et al. Thermal challenges in next generation electronic system-summary of panel presentations and discussions. IEEE Trans on Comp Packag Technol 2002; 25(4): 569-75. [4] Moresco LL. Electronic system packaging: The search for manufacturing the optimum in a sea of constraints. IEEE Trans Comp Hybrids Manufact Technol 1990; 13(3): 494-508. [5] Sandborn PA, Moreno H. Conceptual Design of Multichip Modules and Systems. MA: 22 Kluwer; 1994. [6] Sherwani NA, Yu Q, Badida S. Introduction to Multichip Modules. New York: Wiley; 1995. [7] Sherwani NA. Algorithms for VLSI Physical Design Automation. 3rd, MA: Kluwer; 1999. [8] Chao KY, Wong DF. Thermal placement for high-performance multi-chip modules. Intern. Conf. on Computer Design; 1995, p. 218-23. [9] Lampaert K, Gielen G, Sansen W. Thermally constrained placement of small-power IC’s and multi-chip modules. Thirteenth IEEE SEMI-THERM Symp; 1997, p. 106-11. [10] Tsai CH, Kang SM. Cell-level placement for improving substrate thermal distribution. IEEE Trans on Computer-Aided Des 2000; 19(2): 253-66. [11] Tang MC, Carothers JD. Consideration of thermal constraints during multichip module placement. Electronic Letters 1997; 33(12): 1043-5. [12] Beebe C, Carothers JD, Ortega A. Object-oriented thermal placement using an accurate heat model. Proc of the 32nd Hawaii Intern Conf on System Sciences; 1999, p. 1-10. [13] Huang YJ, Guo MH, Fu SL. Reliability and routability consideration for MCM placement. Microelectronics Reliab 2002; 42: 83-91. [14] Lee J. Thermal placement algorithm based on heat conduction analogy. IEEE Trans on Comp Packag Technol 2003; 26(2): 473-82. [15] Quinn N, Breuer M. A forced directed component placement procedure for printed circuit boards. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst 1979; 26(6): 377-88. [16] Osterman MD, Pecht M. Placement for reliability and routability of convectively cooled PWB's. IEEE Trans on Computer-Aided Des 1990; 9(7): 734-44. [17] Eisenmann H, Johannes FM. Generic global placement and floorplanning. Proc of the ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conf; 1998. p. 269-74. 23 [18] Mo F, Tabbara A, Brayton RK. A force-directed marco-cell placer. Proc of Intern Conf on Computer-Aided Des; 2000. p. 177-80. [19] Lall P, Pecht M, Hakim EB. Influence of temperature on microelectronics and system reliability. FL: CRC Press; 1997. [20] Steinberg DS. Thermal stress failures of surface mounted components. In: Bar-Cohen A, Kraus AD, editors. Advances in thermal modeling of electronic components and system. vol. 3, New York: ASME/IEEE Press; 1993, p. 257-302. [21] Ellison GN. Thermal computations for electronic equipment, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold; 1983. [22] Dean DJ. Thermal design of electronic circuit boards and packages. Scotland: Electrochemical Publications Ltd; 1985. [23] Palisoc AL, Lee CC. Exact thermal representation of multilayer rectangular structures by infinite plate structures using the method of images. J Appl Phys 1988; 12(64): 6851-7. [24] Burkard RE, Cela E. Linear assignment problems and extensions. In: Du DZ and Pardalos PM, editors. Handbook of combinatorial optimization, supplement volume A. MA: Kluwer; 1999, p. 75-149. [25] Kirkpatrick S, Gelatt CD, Vecchi MP. Optimization by simulated annealing. Science 1983; 220(4598): 671-80. [26] Sait SM, Youssef H. Iterative computer algorithms with applications in engineering. California: IEEE Press; 1999. [27] Sechen C, Sangiovanni-Vincentelli A. The timberwolf placement and routing package. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 1985; 20(2): 510-22. [28] Johnson DS, Aragon CR, Mcgeoch LA, Schevon C. Optimization by simulated annealing: an experimental evaluation. PartⅠ. AT&T Bell Lab, Murray Hill; 1987. [29] Aarts EHL, Lenstra JK. Local search in combinatorial optimization, UK: Wiley; 1997. 24 [30] Shahookar K, Mazumder P. VLSI cell placement techniques. ACM Computing Surveys 1991; 23(2): 143-220. [31] Katopis GA, Becker WD, Mazzawy TR, Stoller H. Packaging 1000 MIPS for IBM’s S/390 G5 server. Electronic Components and Technology Conf 1999; p. 680-5. [32] Katopis GA, Becker WD, Mazzawy TR, Smith HH, Vakirtzis CK, et al. MCM technology and design for the S/390 G5 system. IBM J of Research and Development 1999; 43(5/6): p. 21-49. [33] Goth GF, Zumbrunnen ML, Moran KP. Dual-Tapered-Piston (DTP) module cooling for IBM enterprise system/9000 systems. IBM J of Research and Development 1992; 36(4): p. 805-16. 25