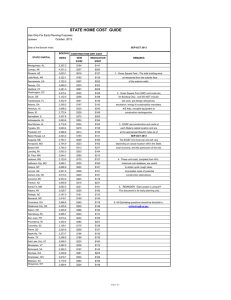

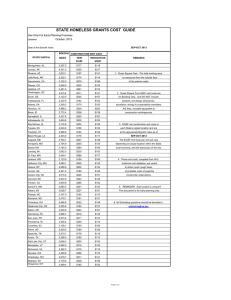

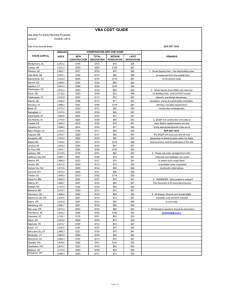

Online Consultation on the CFS Global Strategic Framework Draft One

advertisement