JOHNS HOPKINS

advertisement

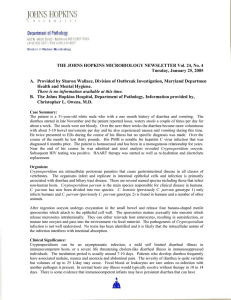

JOHNS HOPKINS U N I V E R S I T Y Department of Pathology 600 N. Wolfe Street / Baltimore MD 21287-7093 (410) 955-5077 / FAX (410) 614-8087 Division of Medical Microbiology THE JOHNS HOPKINS MICROBIOLOGY NEWSLETTER Vol. 25, No. 16 Tuesday, August 15, 2006 A. Provided by Sharon Wallace, Division of Outbreak Investigation, Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. There is no information available at this time. B. The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Department of Pathology, Information provided by, Aaron A. Tobian, M.D., Ph.D. Clinical Presentation: A 47 year-old Hispanic female nurse with a past medical history of cervical cancer s/p total abdominal hysterectomy and osteomyelitis presented with a four week history of diarrhea. After two weeks, she began to have upper abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting accompanying the diarrhea, and was evaluated at a community hospital. After three days, she was told she had “normal blood work and stool studies” and discharged with Flagyl. The abdominal pain became worse, she lost ten pounds, was unable to take much food or water by mouth, and had watery-to-loose stools ten times a day (including one to two at night). She had no overt fever, chills, or jaundice. Her physical exam did not show any lymphadenopathy; the abdominal exam had normoactive bowel sounds and was diffusely tender with no rebound, and no blood in the rectum. She was admitted to Johns Hopkins Hospital with a white blood cell count of 6,200. Microbiology found Cyclospora cayetanesis oocyts in the stool. Organism: Cyclospora cayetanesis was first described in humans living in Papua New Guinea in 1979 (1). It was referred to as “cyanobacterium-like bodies” until Ortega et. al. induced sporulation and confirmed the genus Cyclospora (1, 2). Cyclospora cayetanesis was named after the Universidada Peruana Cayetanol Heredia in Lima, Peru, which was a major research site for the infection (3). The life cycle has not yet been fully described due a lack on an in vitro model. The current model, however, hypothesizes that organisms emerge from the human host in an unsporulated state. Sporulation occurs after four to five days in the outside environment, and then humans have the possibility of once again becoming infected; thus, person-to-person transmission is rarely suspected (1). Clinical Significance: Individuals infected with Cyclospora cayetanesis generally describe a “flu-like” illness that involves nausea, vomiting, anorexia, fatigue, weight loss, and explosive watery diarrhea (2). The diarrhea usually occurs at least six times daily. Fever occurs only in about 25% of patients (3). The illness usually lasts from two to seven weeks, but can be prolonged in immunosuppressed hosts. Cyclospora infection is common in HIV patients and the illness tends to be more severe and last longer (4). In the United States and other Western countries, however, HIV patients often receive Bactrim prophylaxis which potentially limits the infection. Epidemiology: Initially infection with Cyclospora cayetanesis was thought to be restricted to tropical and sub-tropical developing countries, such as Nepal and Peru (1). In the late 1990s, however, there were at least 1000 reported cases annually in the United States (1). One study in the United States, found that two samples of 315 routine stool samples evaluated for ova and parasites contained Cyclospora cayetanesis (5), which is consistent with other studies showing a prevalence of 0.1 to 0.5% of stool samples (3). This organism is mainly transmitted by contaminated food and water. Cyclospora has been associated with the consumption of fresh basil, imported raspberries, green leafy vegetables, Asian freshwater clams, and foreign travel (1). Infection generally occurs seasonally with spring and summer months being the peak seasons in the United States (3). Laboratory Diagnosis: The transmission stage of Cyclospora cayetanesis is the oocyst which is spherical, 8-10 m in diameter and consists of a nonrefractile external well that contains a cluster of refractile globulins (1, 6). Unsporulated oocysts are shed into the feces of infected patients and can thus be detected by a microscopist. Oocysts from stools preserved in formalin significantly deteriorate after just a few days; thus, samples should be evaluated soon after they are obtained. Initially samples are concentrated with either Sheather’s sucrose solution to a wet mount slide or with a formalin-ethyl acetate concentration procedure (1). The chances of detecting Cyclospora oocysts in specimens that have not undergone a concentration procedure are reduced by up to 40%. Specimens being screened for Cyclospora oocysts are often evaluated by UV microscopy. C. cayetanesis oocysts autoflouresce under ultraviolet light microscopy and appear either blue or green (1). It is critical to note that Cyclospora oocysts (7.7 to 10 m) are almost twice the size of Cryptosporidium oocysts (4 to 6 m) (1). If oocysts are identified by UV microscopy, they are confirmed as Cyclospora by using either Ziehl-Neelsen or Kinyoun stains. Cyclospora is variably acid-fast and appear dark red to almost purple with the Kinyoun stain. A recent study demonstrated that Cyclospora oocysts can be detected in fecal samples by flow cytometry. This limited study of 42 samples was 100% specific and even more sensitive than the gold standard of microscopy (7). The advantage of flow cytometry is that it is largely automated; however, it is a new technique that would require validation for so few samples. At Johns Hopkins Hospital, the microbiology laboratory must be informed that Cyclospora is suspected since it is not detected by routine O&P examinations. The sample is then concentrated, evaluated for autoflourescent oocysts, confirmed by Kinyoun staining, and the diameter is measured to ensure the oocysts are the correct size. Treatment: The standard treatment for Cyclospora cayetanesis is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) twice daily for seven days (3). Due to the high relapse rate among HIV-positive patients, they should be treated four times daily for ten days with chronic prophylaxis three times per week (3). All cases of Cyclospora cayetanesis should be reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. References: 1. Shlim, D.R. Cyclospora cayetananis. Clin. Lab Med. 2002; 22: 927-936. 2. Ortega Y.R., C.R. Sterling, R.H. Gilman, V.C. Cama, and F. Diaz. Cyclospora Species – A New Protozoan Pathogen of Humans. NEJM. 1993; 328: 1308-1312. 3. Keystone, J.S. and P. Kozarsky. “Isospora belli, Sarcocystis species, Blastocystis hominis, Cyclospora.” Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious disease. 5th ed. Philadelphia; Churchill Livingstone, 2000. 4. Pape, J.W., R.I, Verdier, M. Boncy, J. Bonct, and W.D. Johnson. Cyclospora Infection in Adults Infected with HIV: Clinical Manifestations, Treatment, and Prophylaxis. Annals Intern. Med. 1994; 121: 654-657. 5. Ribes, J.A., J.P Seabolt, and S.B. Overman. Point Prevalence of Cryptosporidium, Cyclospora, and Isospora Infections in Patients Being Evaluated for Diarrhea. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2004; 122: 28-32. 6. Wurtz, R. Cyclospora: A Newly Identified Intestinal Pathogen of Humans. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1994; 18: 620-623. 7. Dixon, B.R., J.M. Bussey, L.J. Parrington, and M. Parenteau. Detection of Cyclospora cayetanensis Oocysts in Human Fecal Specimens by Flow Cytometry. J Clin Micro. 2005; 43: 2375-2379.