Strategies to Support Children’s Learning

advertisement

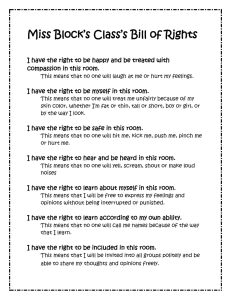

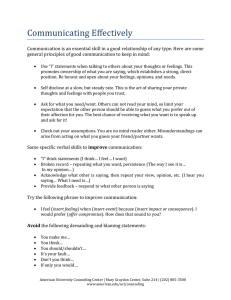

Strategies to Support Children’s Learning Betty S. Williams, MSW, NSCC Parent Education Instructor, November 1, 2008 Research on brain development indicates that young children learn best through play, exploration, hands-on interaction with appropriate materials, in a safe, environment with caring adults. Rather than teaching them directly in the ways we may recall from elementary school, such as quizzing, directions, praise, or rewards, I encourage you to try some of these techniques that have been proven to effectively help children learn in ways that build their confidence in themselves as learners. I have found these methods to facilitate learning in positive ways and hope you will as well. 1. Observe children and describe what you see Be a careful observer of children’s behavior and describe their actions in specific descriptions in order to encourage that behavior, and support their language development. Try to use objective language, with sportscaster detail. For example, when children are building with blocks, the adult can say, “I see you have the red block on top of the yellow block,” rather than quizzing the children about color names. Quizzing interrupts the child’s focus on the process of thinking and decision-making about their play. It is also fine to be quiet until you think some encouragement is needed. 2. Support Children’s Creativity and Exploration Try to avoid praise, such as constantly saying “Good job!”, which leads children to be more oriented to adult approval rather than internal motivation. Instead, use descriptive language to comment on children’s artwork and creative efforts. Rather than asking, “What is it?” say “What would you like to tell me about your work?” or just describe it, such as “I see a lot of blue from the top of the page to the bottom.” Open-ended questions support the child’s creative thinking process rather than imposing an adult agenda. Artwork for young children should never be based on an adult model, as the process is what is valuable for their creative learning, not the product. 3. Facilitate Problem-Solving and Appropriate Choices The use of descriptive language can also assist children in developing problem-solving skills. If a child grabs at a toy that another child has the adult can say, “I see Tom’s hands on that.” If the child persists, we can provide suggestions, or ask the children for suggestions to solve the problem depending on their age and language abilities. With very young children, I may put my hand on the toy to prevent tugging and someone getting hurt. I might suggest, “You can ask Tom for a turn, by saying ‘turn’, and if Tom isn’t ready, then let’s ask Tom to give it to you when he’s done.” For a toddler, keep the words to a minimum, such as “turn, done, stop.” A child who is having something grabbed can be encouraged to hold on tight, if they seem to be upset and don’t know what to do. We can coach them to say, “My turn, you can have it when I’m done.” The adult can then say, “Let’s find something to do while you’re waiting.” For children without language, you can model the language that they can use to solve problems in the future. It is helpful to teach children on both sides of a dispute what the appropriate language is to solve a problem. Avoid asking a question when there really is not a choice that you want to offer the children. Instead of saying, “Can you clean up now?” it is often more effective to say, “Let’s clean up now,” and then describe the actions of children who are helping, such as “Zoe is putting the blocks in the bucket.” Focus on providing two yeses as choices for every no. Give brief reason, such as, “Pushing hurts, let’s touch gently, or come use the push toys.” When a child hurts another, separate them, let them know what happened and focus on what to do instead. If a child is becoming overwhelmed and/or losing control, have them “take a break” by helping them move to another area, preferably an uncrowded area so they can have some space for calming down. It is also helpful to encourage empathy by pointing out and describing facial expressions, such as saying, “Look at his face, he is sad because pushing hurts his body” or “those words hurt his feelings.” For older children, it is helpful to describe the situation and ask them for ideas to solve the problem. An example is “I see you both want to use that toy. How can we solve this problem?” If the children don’t come up with acceptable solutions, the adult can offer a couple of choices and involve the children in making a decision that is acceptable to everyone involved. 4. Help children learn respect for others Anti-bias approaches developed for young children include actively confronting exclusive and discriminatory language and behavior, empowering children to use assertive language to express their feelings and thoughts, and taking advantage of teachable moments to help children learn positive social skills to build respectful relationships with people from all cultures and backgrounds. Examples (from Roots and Wings, by Stacey York) of what to say when children exhibit hurtful, discriminatory actions are: Name feelings: “You look really sad, Juan. It hurt your feelings when Daniel called you ‘brown skin’.” Express empathy: “Yes, Damani, I know how you feel. It hurts when people call us names.” Voice your own feelings: “I’m uncomfortable with the way you are playing cowboys and Indians. I’m worried that you think Indians are bad guys that hurt people.” Respect the conflict and confusion: “It’s hard to use your words when you are so upset.” Answer children’s questions with honest, accurate information: “Yes, Pham’s skin is darker than yours and her eyes are shaped differently. She looks like her mom and dad, just like you look like your mom and dad.” Protest: “I don’t like it when you call Marcus ‘Fattie.’ That’s name-calling and it hurts his feelings.” Describe the behavior you want: “In our room we all play with one another. You may choose who to play with but you may not leave someone out of your play because of how they look or how they talk. Our classroom rule is to treat everyone respectfully and fairly.” Help problem-solve and set limits: “Fabrizio wants to play with you again. If you two play together, what will you need to feel safe?” Explain hurtful stereotypes: “Mariah, I took the book you brought to school today off the book shelf because it has pictures of people that are untrue and unfair.” Young children are forming their ideas about how the world works, and they learn as much by our omissions as what we say and do. Don’t hesitate to share your values with children so that they learn from a young age to treat others with respect rather than allowing fear of differences to turn into prejudice and discrimination. Children learn best through caring relationships with adults who model the behaviors they want children to learn. So relax and have fun with them! Resources: Developmentally Appropriate Practices, National Association for the Education of Young Children Positive Discipline for Preschoolers, Nelsen, Irwin & Duffy The Power of Play, Elkind Promoting First Relationships, Kelly, Zuckerman, Sandoval, & Buehlman Roots and Wings, York