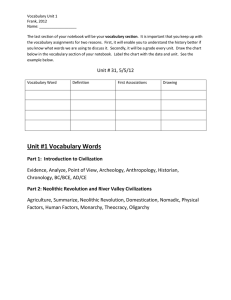

Document 15676116

advertisement

HUNTERGATHERER S TO FARMERS HUNTER-GATHERERS TO FARMERS Doing what comes naturally The Neolithic Revolution The first farmers Farm animals Draught animals Neolithic burials Diet, salt and trade Doing what comes naturally Lions and wolves communicate well enough to hunt as a group. Bees can tell each other where the best pollen is. For almost the whole of human history, from at least 3 million years ago, mankind has lived by carrying out these two basic acitivities of hunting (or fishing) and gathering edible items of any kind (from fruit to insects). We are unusual among animals in combining the two functions, and we have been greatly helped in both by the development of language. But basically, as hunter-gatherers, we have lived by doing what comes naturally. It is true that human beings have dignified both activities with elaborate ritual and with much attention to the spirits of nature. And it is true that in human societies the business of hunting and gathering has involved specialization, with men doing the hunting and women much of the gathering. And humans, unlike most animals, carry the food home and share it, rather than consume it there and then. But all this is a result of our ability to communicate, to speculate, to rationalize. It does not alter the fact that for 3 million years Stone Age man, the hunter-gatherer, engages in an activity as natural as the swoop of a hawk or the grazing of a horse. The Neolithic Revolution: 10,000 years ago The change comes a mere 10,000 years ago, when people first discover how to cultivate crops and to domesticate animals. This is the most significant single development in human history. It happens within the Stone Age, for tools are still flint rather than metal, but it is the dividing line which separates the old Stone Age (palaeolithic) from the new Stone Age (neolithic). It has been aptly called the Neolithic Revolution. The strange thing is that this revolution occurs independently in separate parts of the world - the Middle East, for example, and America. How can this unlikely coincidence occur? Part of the reason may be the ending of the most recent cold phase of the present ice age (see Ice Ages). This creates new temperate regions, in which humans can live comfortably. By contrast many of their main victims in the chase cannot survive in the changed climate. Herds of bison move to colder regions. Mammoths become extinct. But plants of all kinds grow more easily in the new temperate zones. It is not hard to imagine, in these circumstances, a strong human impulse to abandon the pursuit of the bison and to stay, instead, in a region where edible plants are now growing in sufficient profusion to seem worth encouraging and protecting (by weeding around them, for example). Some human groups adapt to a new way of life. Others go after the bison. If the impulse is to settle, there is also a strong incentive to ensure that animals remain nearby as a supply of food. This may involve attempts to herd them, to pen them in enclosures, or to entice them near the settlement by laying out fodder. The first farmers: from 8000 BC From weeding around a plant, or perhaps watering it in a dry spell, it is a small step to collecting its seeds and planting them in a protected spot where they will have a better than average chance of growing. From penning in animals, to kill them when needed, it is a small step to keeping them until their offspring are born. In any one place the process will be gradual. Cultivated crops or domesticated animals form at first only a small part of a community's diet, most of it coming still from hunting and gathering. In each place where the change happens, its pattern is no doubt different. But in the Middle East, in America, in China and southeast Asia, the change does occur. The earliest place known to have lived mainly from the cultivation of crops is Jericho. By around 8000 BC this community, occupying a naturally well-watered region, is growing selected forms of wheat (emmer and einkorn are the two varieties), soon to be followed by barley. Though no longer gatherers, these people are still hunters. Their source of meat is wild gazelle, cattle, goat and boar. It is no accident that Jericho is also the first known town, with a population of 2000 or more. A pioneering agricultural community, surrounded by other tribes dependent on gathering food, offers easy pickings which will need vigorous protection. Jerico has protective walls and a tower. Sheep and goats, cattle and pigs: 9000-7000 BC The first animals known to have been domesticated as a source of food are sheep in the Middle East. The proof is the high proportion of bones of one-year-old sheep discarded in a settlement at Shanidar, in what is now northern Iraq. Goats follow soon after, and these two become the standard animals of the nomadic pastoralists - tribes which move all year long with their flocks, guided by the availability of fresh grass. Cattle and pigs, associated more with settled communities, are domesticated slightly later - but probably not long after 7000 BC. The ox may first have been bred by humans in western Asia. The pig is probably first domesticated in China. Draught animals: from 4000 BC Of the four basic farm animals, cattle represent the most significant development in village life. Not only does the cow provide much more milk than its own offspring require, but the brute strength of the ox is an unprecedented addition to man's muscle power. From about 4000 BC oxen are harnessed and put to work. They drag sledges and, somewhat later, ploughs and wheeled wagons (an almost simultaneous innovation in the Middle East and in Europe). The plough immeasurably increases the crop of wheat or rice. The wagon enables it to be brought home from more distant fields. With these developments in place, the transition to settled communities is complete - from hunter-gatherer to farmer. But the Neolithic Revolution only spreads to areas which are suitable for farming. In the jungles of the world, hunting and gathering remains the standard way of life for human communities until the 20th century. An intermediate stage, that of nomadic pastoralism (moving with the flocks to new pastures), prevails in semi-barren regions. The use of a draught animal is a valuable but not an essential part of this farming revolution. No beast powerful enough for the purpose is available in America, but this does not prevent agriculture and civilization from evolving. Neolithic burials: from 8000 BC As soon as communities remain settled in one place, as a result of the Neolithic Revolution, the burial of their dead becomes a matter of intense concern. An early solution is to keep them within the family home, buried beneath the floor or even under the bed. In Jericho, from about 8000 BC, burials are found under the floors of houses as well as in nearby vacant lots. In Catal Huyuk, 1500 years later, the more normal place is within the house - under the brick and plaster platform which is used for sleeping and other everyday purposes. The procedure in Catal Huyuk is for the dead body to be exposed outside the town, where vultures - with the subsequent assistance of insects - strip the bones dry. When the skeleton is ready for burial, the sleeping platform in the house is opened up; the present occupants are rearranged to make space for the newcomer; and the platform is bricked up again and plastered over. A society with elaborate shrines must certainly have accompanied such an event with considerable ritual. The majority of burials are without funeral gifts, but in a few cases the jewels of women and the weapons of men are buried with them. Diet, salt and trade: from 4000 BC The new diet of settled farmers - predominantly vegetarian, with meat now an occasional luxury - results in one small but significant development. Salt becomes an important commodity in human trade. A physical necessity of human life, salt exists in sufficient quantity in a diet of milk and of raw or roasted meat. It is not present in vegetables, grain or boiled meat. Agriculture in many areas of the world (freshwater districts without mineral deposits of sodium chloride) only becomes possible if a trade in salt is established. As a result salt features in many of the most important trading systems of the world. The caravan routes crossing the Sahara are a prime example. Language and custom reflect this central role of salt in human civilization. In English it is a term of praise if a man is considered 'worth his salt' or is judged to be 'the salt of the earth'. In a medieval banquet an inferior guest, seated at the bottom end of the table, is described as being 'below the salt'. The importance of this simple mineral during two millennia is even reflected in an English term for wages. A Roman soldier is given an allowance to buy his salt (sal in Latin). This allowance is his salarium. Office workers, 2000 years later, take their supply of salt entirely for granted. But they still draw their salaries.