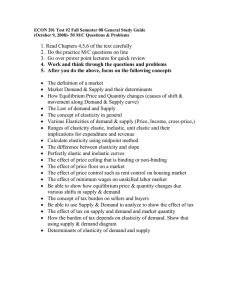

Econ 201 Spring 2009 Lecture 4.1 Elasticity

advertisement

Econ 201

Spring 2009

Lecture 4.1

Elasticity

Taxes & Subsidies

4-28-09

Demand Elasticity Calculation

• Economist use the price elasticity of demand

to summarize how responsive quantity

demanded is to price

• Demand curves are not always linear; and

responsiveness can change with price

% change in Qd

elasticity

% change in price

Overview of Elasticity

• Own-price demand

elasticity

• Measures movement (Qd)

along the demand curve in

response to a change in

the (own) price of the

good

xx (Qx d / Qx d ) /(Px / Px )

• Cross-price demand

elasticity

– Measures change in Qd

due to a shift in demand

xy (Qx d / Qx d ) /(Py Py )

xx (Qx d / Qx d ) /(Px / Px )

Demand Elasticity

for the linear demand curve

Demand Elasticity

$2

$3

$4

$5

-2

$6

0

$7

-10

-4.5

-2.66667

-1.75

-1.2

-0.83333

-0.57143

-0.375

-0.22222

$8

0.10

0.11

0.13

0.14

0.17

0.20

0.25

0.33

0.50

Ed

$9

-1

-0.5

-0.33333

-0.25

-0.2

-0.16667

-0.14286

-0.125

-0.11111

Den (P)

$10

Num (Q)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Price

price per unit

Qd

$10

$9

$8

$7

$6

$5

$4

$3

$2

$1

-4

-6

Ed

-8

-10

-12

Elasticity

Calculating Elasticity

•

Elasticity is calculated at a point on the demand curve

– Several choices:

• Initial point, final point, average (arc) elasticity

– At $5 -> Qd = 6; At $6 ->Qd = 7

– Elasticity of demand (intital point):

d

(Q1 Q2 ) / Q1

(6 7) / 6

(1/ 6)

5

( P1 P2 ) / P1 ($5 $4) / $5 (1/ 5)

6

Why Bother?

– Affect’s a firm’s

revenues & profitability

– Affect’s pricing

strategy

Demand for Eggs

Individual A

Individual B

50

$ Per Dozen

• Own-price elasticity

tells us how

responsive quantity

demanded is to price

changes

40

30

20

10

0

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 32

# Eggs per month

What Affects (Own) Price Elasticity

• Availability and closeness of substitutes

– Fewer close substitutes -> inability to shift

consumption to other goods -> can only

decrease current consumption

• Demand will be more inelastic

• Proportion of Income

– Lower % of income -> lower price sensitivity > lower price responsiveness (inelastic)

• Affordability study

What Does Cross-price

Elasticity Tell Us?

• Sign of cross-price elasticity is important

– (+) sign -> increases in price (Py) of other

good results in an increase in consumption of

this good (Qx)

• Shifts demand for X to the right -> substitute

– (-) sign -> increase in Py results in decrease

in Qx

• Shifts demand for X to the left -> complement

More on Cross-Price

• Magnitude of the shift (or elasticity) tells

us:

– If a substitute

• How close/good a substitute

– Closer substitute -> bigger shift in demand for X

» Larger cross-price elasticity

– If a complement

• How important it is to “joint” consumption

– E.g. if “fixed proportions” -> bigger shift in demand for X

» Large (absolute) cross-price elasticity

Why Else It Might Be Useful

• Firm’s perspective

– Strategic:

• Substitutes: allows us to anticipate changes in

demand to competitors prices

• Complements: allows us to anticipate the impact

of changes in prices of suppliers on the demand

for our product

• Policy Evaluation

– Evaluate impact of taxes used to subsidize

other goods/services

Evaluating the Impact of

Government Intervention

• Policy Instruments Available

– Taxes

• Typically: per-unit tax on output

• Others: lump-sum, value added (VAT)

– Subsidies

• Rebate on per-unit produced

– Price Floors

• Minimum price that can be charged (e.g., minimum wage)

– Price Ceilings

• Limit on the maximum price that can be charged (WIN)

– Quotas

• Limits on amounts produced/imported

• Infant industry/protectionism

Key Assumptions

• No Market Failure

– No externalities

• i.e., benefits or costs that are not accounted for in

the marketplace (e.g., no free riders, no pollution

costs that aren’t captured in the product’s price)

– Perfectly competitive markets

• Large # of suppliers and buyers

• Evaluate Market Efficiency

– Look at losses/gains in consumer/producer

surplus

Effect of a Tax on the Supply Curve

• To the supplier: increases per-unit costs

– Shifts supply curve to the left

• Reduces amount supplied and raises the

market clearing price

• How do we measure the effects of the tax?

– Efficiency or deadweight losses are losses in

consumer and producer surplus relative to the

“ideal” market

How Do We Analyze the Effects of

Taxes and Subsidies

• The efficient ideal market

– “perfectly competitive” market

• Consumers and suppliers are price-takers, i.e. have no

market power

Effect of a Tax on the Supply Curve

Deadweight Loss

How Do We Evaluate the

Impact of a Tax?

• Framework for analysis is comparing

benefits and costs

– Costs of the tax

• Reduction in equilibrium quantity

• Increase in price paid

– Costs can be calculated as the deadweight

loss in $ if demand and supply curves are

known

What Are the Benefits?

• Depends on what we do with the taxes

– Suppose we use it to subsidize another good

• Subsidy appears as a reduction in per-unit costs to

the firm getting the subsidy

Figure A-1.

The Deadweight Loss from a Price Subsidy

SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office.

Evaluating The Impact

• Costs:

– Deadweight loss: sum of reduction in consumer and

producer surplus for the taxed good

• Reflects reduction in Qd and higher price paid

• Benefits

– Gain in CS and PS from subsidized cost

• Will Benefits > Tax

– Depends on the relative demand elasticities for the 2

goods

Evaluating the Impact

• “A Positive Analysis” (Distributional

Consequences)

– Who gains/loses from the tax and subsidy?

– Both producers and consumers of the taxed

good lose (in terms of lost surpluses)

– Relative demand/elasticities determine who loses most

» More inelastic demand -> greater is CS loss

– Producers and Consumers of subsidized

good win (lower price and more Q)

– Relative demand supply elasticities determine who

benefits most

Total Social Welfare

•

Ideally the impact of a program should be

evaluated as: {Pareto efficient}

–

–

–

•

1) can any one (or more) person’s welfare be

improved

2) without any one else’s welfare being reduced

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pareto_efficiency

More realistically: Could the winners

compensate the losers? {Pigouvian}

–

–

Is the deadweight loss of the taxed good less than

the surplus gain from the subsidized good?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pigovian_tax

So Do They Do This

in the Real World?

• The Senate has approved a bill that would

require gasoline producers to blend 36 billion

gallons of ethanol into gasoline by 2022, an

increase from the current standard of 7.5 billion

gallons by 2012. The House did not include such

a provision in the version it passed, and it is

uncertain whether any final legislation will

emerge this year and what it will say about

ethanol if it does.

• What would be the impact of such legislation on

the demand for ethanol? For corn-based food

prices?