Demand for Use of Hospital and Long-term Residential Care Services

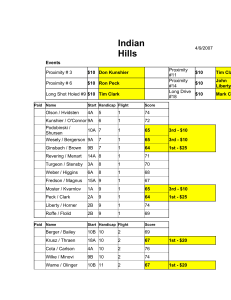

advertisement

Demand for Use of Hospital and Long-term Residential Care Services in Relation to Proximity to Death among Older People in Finland Mike Murphy, London School of Economics Pekka Martikainen, University of Helsinki Prepared for Experts' Seminar on Ageing and Long-Term Care Needs London School of Economics, Friday 20 May 2011 Number of people projected to live to age 100, United Kingdom Males Age in 2010 Total aged under 100 Number Population to reach in 2010 age 100 (000s) (000s) Females Proportion Population reaching in 2010 100 (%) (000s) Number to reach age 100 (000s) Proportion reaching 100 (%) 30,607 4,441 14.5% 31,604 6,315 20.0% 0-15 5,926 1,359 22.9% 5,649 1,720 30.4% 16-50 15,025 2,272 15.1% 14,884 3,197 21.5% 51-65 5,444 512 9.4% 5,654 818 14.5% 66-99 4,211 299 7.1% 5,416 579 10.7% Table 1, Department for Work and Pensions, Ed Price (ed.price@dwp.gsi.gov.uk), Number of Future Centenarians, December 2010 Projections of National Long-term Care Expenditures for the Elderly: US Year Billion Dollars (2000 levels) 2000 123 2020 207 2030 295 2040 346 Source: "Projections of expenditures for long-term care services for the elderly," CBO 1999. Future demand for long-term care in the UK: Summary of projections of longterm care finance for older people to 2051 Long-term care expenditure in the UK would need to rise by around 317 per cent in real terms between 2000 and 2051 to meet demographic pressures and allow for real rises in care costs of 1 per cent per year for social care and 1.5 per cent per year for health care (central base case assumptions £12.9 billion to £53.9 billion). (Wittenberg et al Sept 2004) The Background: e.g. Wanless • People’s health care needs are higher as they approach death. o Acute health care costs are strongly associated with proximity to death. o More than a quarter of all acute health care costs are incurred in the last year of life • Part of older age groups’ higher cost reflects the greater number of people close to death as well as age related health care needs. • Demographic changes have had less of an impact on health spending than often thought as proximity to death has a larger impact on health care costs than age. The Background: (contd) • The costs of acute care are strongly associated with proximity to death, regardless of age at death, i.e. health costs for older people are higher mainly because they are closer to death. • Analysis of demographic pressures that ignores specific costs in the last year of life (i.e. the costs of death) risks overstating its impact. So, need to consider people in their last year of life (decedents) and those not (survivors) • Social care costs increase with proximity to death, but also increase with age. (Wanless Chapter 3 p 43) Wanless (p. 21) • “It is therefore possible that the effect of an ageing population will be to postpone rather than increase health service costs. Previous studies have suggested that demographic change will add less than 1 per cent a year to costs. If ageing postpones costs the impact on costs could be lower.” BUT the evidence suggests that the need for social care services rises sharply with age. (McGrail et al 2000) • Need to consider all use of services in relation to age, proximity to death & other factors Background to long-term institutional care • LTC c. 1.5% of GDP in OECD countries 2008 (http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/31/8/46458681.xls >3% Sweden & Netherlands) • With population ageing the demand and costs of long-term care are expected to grow rapidly • At the proximate level entry to institutions is determined by health and cognitive and physical functional status, but distal socio-demographic factors are also important Total expenditures (Hoover et al US$) 65-74 75-84 85+ Non-terminal year 5719 7832 13895 Last year of life 37043 38529 36985 “As Chart 2.7 shows, the cost of the last year of life does not rise with age; if anything, it appears to fall.” Average HRG costs for decedents and survivors (all population) 8000 7000 Survivors Costs(£s) 6000 Decedents 5000 4000 3000 2000 1000 88 85 82 79 76 73 70 67 64 61 58 55 52 49 46 43 40 0 Age (years) Graham, B & Normand, C (2001) Proximity to death and acute health care utilisation in Scotland. Demographic change and health service and social care use • Although having clear implications for patients’ quality of life, care costs and mix, and clinicians’ end-of-life care decisions, few studies investigating the contribution of age and proximity to death to service use have: o Looked simultaneously at health and social care use o Included socio-demographic information o Assessed the impact of changing patterns of disease and cause of death Annual number of deaths, EU−27 (000s) Data & Methods • Few countries have good data on LTC (and sometimes on joint use of community and hospital facilities – incompatible record systems, confidentiality issues regarding linkage of records etc) • Some countries have good integrated longitudinal record systems such as Finland Data source • A 40 % random sample of the Finnish population aged 65 and older at the end of 1997 drawn from population registers with information on socio-demographic factors at baseline was followed to death by cause in 1998– 2003 or to the end of 2003. The use of hospital and longterm institutional care was assessed in 1995–2003 up to seven years prior to death or end of follow-up. • The outcome measure is days spent in hospital/long term care (not costs) Study data (40% sample of those 65+) STAKES Institutional care: Care episodes Date of entry Date of exit Type of institution STAKES Sociodemographic factors: Sex Marital status Living arrangements Education Social class Income Housing Partner Region Date/cause of death Statistics Finland Use of homecare services STAKES Supply of care: Regional coverage of institutional care Health: Medication Hospital discharge STAKES Pension institute Definitions of long-term institutional care & hospital care • Days in long-term care includes days spent in nursing homes, service homes with 24-hour assistance, and rehabilitation care (lasting for over 90 days or confirmed by a long-term care decision). • Hospital care refers to days spent in either a hospital or a health centre, and included both overnight stays and day surgery. • Total care refers to the sum of the two groups above. Average Number of Days in Hospital/LTC, by Sex & Survival status Finland Average Number of Days in Hospital/LTC by Marital Status, Finland Age-adjusted average number of hospital, long-term & total care days in the each of the previous seven years by survival status and sex Age-adjusted average number of hospital, long-term and total care days in the previous seven years before death by cause of death and sex Age-adjusted average number of total care days in the previous seven years before death from dementia Total care, men Total care, women 250 250 200 200 Days Days 150 100 50 150 100 50 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Year before death / end of follow-up Kuolleet, naimattomat Deceased, married Deceased, non-married 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 Year before death / end of follow-up Kuolleet, avioliitossaSurvivors, married Survivors, non-married 7 Summary of key results • Use of residential long term care increases more with age than for hospital stays • For the “young old”, decedents use much more hospital care than survivors • For the “old old” differences are less • For long term care, the difference at any age between decedents and survivors is less than for hospital use, but still substantial Socio-economic differentials • Education, social class etc are generally small at any age • Differential survival is more important • Lifetime experiences differ Marital status differentials • Marital status differentials are more substantial than educational ones • Marriage provides more protection for men than for women • Differentials are smaller for decedents than for survivors Cause-specific mortality differentials • Dementia is associated with particularly substantial use of care services (even after age-adjustment) • Cancers are is associated with lower use of care services Percentage of people using social care and inpatient care in the last months of life (N=16,479) Figure 6a in Martin Bardsley, Theo Georghiou, Jennifer Dixon (2010) Social care and hospital use at the end of life www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/publications Monthly costs per user in last 12 months of life Figure 6b in Martin Bardsley, Theo Georghiou, Jennifer Dixon (2010) Social care and hospital use at the end of life www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/publications Average cost per person in last 12 months of life by age group Figure 8 in Martin Bardsley, Theo Georghiou, Jennifer Dixon (2010) Social care and hospital use at the end of life www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/publications authority‐funded social care in the months before death by site Figure 28 in Martin Bardsley, Theo Georghiou, Jennifer Dixon (2010) Social care and hospital use at the end of life www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/publications Summary • Proximity to death is important for acute care, but age is more important for long-term care o cost saving similar to those expected for acute care can not be obtained for LTC in the coming decades • Socio-economic differentials in long-term care use (e.g. by education level) are relatively modest • Marital status differentials are more substantial and future changes in marital status distributions may be important for future projections of elderly use of health and social services. Summary continued … • The population will age considerably in future decades, especially for the oldestold from about 25 years time, & other things being equal: o increasing longevity coupled with a rising trend of dementia is likely to mean a major shift towards higher nursing home care use in the future o the optimistic view that needs may not increase in line with numbers of older people because of the “proximity to death” effect will not occur since the implied additional long-term care needs (bed days in our case) overwhelm these o LTC needs likely to grow more quickly than acute care needs for older people o More need to consider interfaces between • long-term and acute care • institutional and community care .