A HOLISTIC APPROACH FOR ADDRESSING POVERTY AND VULNERABILITY Operationalizing household livelihood security

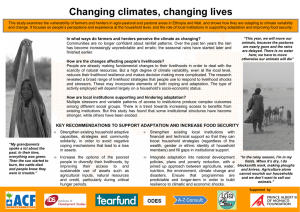

advertisement