Agri-food Value Chain Development and Market Information Systems in the Caribbean Abstract

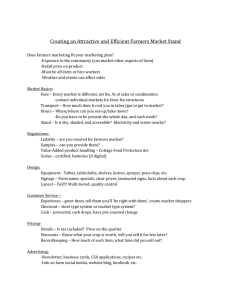

advertisement

Agri-food Value Chain 1 Agri-food Value Chain Development and Market Information Systems in the Caribbean Ardon Iton Caribbean Agricultural Research and Development Institute e-mail: aiton@cardi.org Abstract Recent years have seen increased discussion of the role of Market Information Systems (MIS) and Value Chains (VC) in economic development, especially in developing countries. This research attempts to identify how many farmers in Trinidad have used the Trinidad and Tobago National Agricultural Market Information System (NAMIS) and what are some of the key differences between users and non-users of NAMIS from a farmers’ perspective. Using data collected from a survey conducted in 2010, the following criteria were used to develop and test several hypotheses to identify those factors that contribute to use or non-use of NAMIS – size of farm, decision making responsibility, educational level, gender and age. Recently, several other CARICOM countries have expressed an interest in adopting NAMIS or versions of it for use in their countries. It is hoped that by identifying some of the differences between users and non-users of NAMIS, better MIS can be developed in the region and a stronger link can be made between MIS and Value Chain Development (VCD) to help Caribbean farmers participate in high value agri-food value chains and make the transition to market oriented agriculture. Keywords: Value chain development, Market information systems, NAMIS, Information dissemination, Caribbean farmers. Introduction With the escalation of personal computers and other information and communication technologies (ICTs) in the region in the last decade Market Information Systems (MIS) were thought to be a sure way of addressing many of the issues confronting stakeholders in the agri-food value chain. MIS were expected to generate improvements in market efficiency. For small farmers and agribusiness operators in developing countries some development specialists saw MIS as a panacea for small farmer problems, citing such things as: Providing farmers with proper production incentives Expanding market opportunities for small farmers Increasing small farmers’ bargaining power In essence, by removing information asymmetries and reducing transaction costs small farmers would have greater opportunities to sell their produce and labor – participate in high value agri-food chains. However, value chain development is almost impossible if a near-total sharing of information does not exist among all elements of the chain. Information can be considered the glue that holds the value chain members together in harmony. As Verdouw et. al. (2010) states “Information systems are vital enablers of dynamic demand driven supply chains”. The information requirements and use by the stakeholders in the value chain will differ, Agri-food Value Chain but information must be shared for the synchronization of processes and the maximization of chain performance. MIS are seen as one source of providing the numerous chain actors with useful information. From a farmer’s perspective access to timely, relevant and accurate information is critical for meaningful discussions with downstream and upstream members of the chain. But how many of our farmers access and use the information provided by our MIS? Further, how many of our MIS reach our small producers in remote areas? Parikh et. al. 2007, provides a useful overview of some of the problems faced by small farmers and access to MIS. The reasons for non-use of MIS by farmers can be quite varied, and include - age, low levels of literacy, access to the mode of information dissemination (internet), lack of knowledge of using information in decision making etc. The purpose of this study is to find out how many farmers in Trinidad have used The Trinidad and Tobago National Agricultural Market Information System (NAMIS) and what are some of the key differences between users and non-users. That is, what are some of the factors contributing to or hindering the use of NAMIS. It is hoped that based on the findings of this study increased use can be made of NAMIS by farmers as they strive to participate in agri-food value chains. Also, other CARICOM countries will be better positioned to analyze the pros and cons of duplicating NAMIS in their countries as they attempt to facilitate agrifood value chain development by establishing MIS. The rest of this paper proceeds as follows: the second section provides a brief description of NAMIS as it was conceived. Section three outlines the methodology utilized in the study. The analysis of the primary data and a presentation of the results follow this. In section five some conclusions are drawn and a few 2 suggestions made for improving the use of MIS as a means of building stronger value chains. Overview of NAMIS The National Agricultural Marketing and Development Corporation (NAMDEVCO) manages the Market Information System of Trinidad and Tobago titled National Agricultural Market Information System (NAMIS) which was launched in January 2007. The vision of NAMIS was stated then as “To use NAMIS as the tool to provide reliable Information and Market Intelligence, on a real time basis, to all stakeholders by accurately gathering and organizing data using modern methods and techniques to accurately reflect the production status; cost of inputs; sale of produce at the primary/secondary wholesale and retail markets for Sea and Agri-Food products.” The objectives of NAMIS can be succinctly stated as follows: (1) To provide the fresh produce sector and relevant policymakers in T&T with reliable, timely and independent information. (2) To improve agribusiness development, in particular to the development of non-traditional agricultural exports (NTAEs). (3) To help meet foreign demand for fresh produce and seafood, which is growing rapidly in the developed markets of Europe and North America. (4) To provide domestic and international prices, freight costs and supply and demand statistics, plus market access information for the main target markets, crop production issues and a contacts database. (5) Align all agricultural departments of NAMDEVCO to help provide all stakeholders with accurate and timely information as well as to improve the Agri-food Value Chain corporation’s overall polices department processes. 3 and The list of beneficiaries envisaged was: Farmers Exporters Supermarkets Fishermen Agro processors Hotels and Restaurants Caterers Policy Makers, Planners and Researchers General public The primary research undertaken in this study focused on the farmers. How would NAMIS provide information to stakeholders on a timely basis? The following methods were identified: Green Vine – a monthly newsletter Email Telephone Fax Website Directly through staff Interactive Online Access Kiosk Expanded Green Vine E-market Linked to other Agri-Information Systems Table 1 provides a categorisation of the information dissemination methods as listed above. As can be observed from this table ICTs were the preferred means envisaged of getting information to users. However, one must ask how many of our ageing farming population really uses the computer as an information source for farming decisions? As is pointed out in “Impact of Public Market Information Systems (PIMS) on Farmers Food Marketing Decisions: Case of Benin,” by Chogou et. al. 2009, access to information through farmers’ own social networks might be more influential in decision making than PIMS. In table 1 person to person and print media were not the preferred means of dissemination – 9% and 18% respectively. ICTs were the preferred means of information dissemination – 73%. But as Irick M. L. 2008, points out “In order for an information system to have a positive impact on individual performance, 1) the information technology must be utilized, and 2) there must be a good fit with the tasks the technology supports”. Methodology Data was collected by means of questionnaires from a random sample of farmers on a face to face basis and the data analyzed using SPSS. A total of 514 farmers responded to the questionnaire. All questions were not answered by the 514 farmers. The following criteria were used to identify differences between users and non-users of NAMIS: Size of farm Decision making responsibility Educational level Gender Age The hypotheses developed are as follows: Size of farm operation HO: The use of NAMIS by farmers does not depend on the size of farm operation HA: The use of NAMIS by farmers depends on the size of farm operation Decision maker Agri-food Value Chain HO: The use of NAMIS by farmers does not depend on them being the main decision maker for their operations HA: The use of NAMIS by farmers depends on them being the main decision maker of their operations 4 A t-test for equality of means (2-tailed) produced a p-value of 0.000. As the pvalue is lower than 0.05 we reject the null hypothesis. The size of the farmer’s operation does appear to influence the use of NAMIS. Decision maker Educational level of farmer HO: The use of NAMIS by farmers does not depend on their educational level HA: The use of NAMIS by farmers depends on their educational level Gender HO: The use of NAMIS by farmers does not depend on their gender HA: The use of NAMIS by farmers depends on their gender Age of farmer HO: The use of NAMIS by farmers does not depend on their age HA: The use of NAMIS by farmers depends on their age Results Five hundred and fourteen farmers were interviewed of which 87.5% were males. 88.7% of the farmers considered themselves the main decision maker for the farm operation, and 44% of the respondents had used NAMIS. Size of farm operation: A total of 502 farmers indicated the size of their farming operations A total of 501 farmers responded to this question. Table 3 illustrates the contingency table on which the Fisher’s Exact Test was performed. The Fisher’s Exact Test was used in preference to the Pearson’s Chi-square because this is a 2x2 contingency table. A p-value of 0.040 was obtained, so the null hypothesis was rejected. The data suggests that being the main decision maker appears to be more likely to use NAMIS. Educational level A total of 500 farmers indicated their educational level as is illustrated in table 4. For purposes of performing the Pearson’s Chi-square test the no formal educational level was deleted. A p-value of 0.00 was obtained, so the null hypothesis was rejected. The data suggests that the educational level of the farmer appears to have an influence on the use of NAMIS. Those with a higher level of education are more likely to use NAMIS. Gender A total of 502 farmers indicated their gender, of which 405 were males. The Fisher’s Exact Test was used and a pvalue of 0.883 was obtained, so the null hypothesis was not rejected. The data suggests that gender did not appear to have an influence on the use of NAMIS. Age of farmer A total of 512 farmers responded and table 6 illustrates the number of farmers in the Agri-food Value Chain various age groups for both users and nonusers of NAMIS. The Pearson Chi-square test was used and a p-value of 0.117 was obtained, so the null hypothesis was not rejected. The data suggests that age did not appear to have an influence on the use of NAMIS. Table 7 illustrates the means by which farmers received their NAMIS information. As is observed in this table the top three sources were the Green Vine, Newspaper and NAMDEVCO staff in descending order. It is worthy to note that the print media far exceeded the ICTs as a means of obtaining information by the farmers. Fax was not used by any of the farmers. This reinforces the issue of “tasktechnology fit and information systems effectiveness”, Irick, M.L. 2008. 5 information by print media is expected to be more expensive than more modern means, such as, mobile phones and websites, however if our information consumers have not embraced these modern means the effectiveness of MIS will be seriously jeopradized. Demonstrating the benefits of the use of information in decision making in the agribusiness sector is necessary if MIS are to contribute to improved performance of the sector. Further, if the benefits of agrifood value chain management are to be derived in the region, then a stronger link has to be made between MIS and value chain development in the effort to make the transition to a market oriented agricultural sector. References Conclusion and Suggestions Some general conclusions can be drawn with respect to NAMIS. The above analysis suggests that the information system is not widely utilized by farmers – less than 50%. Of those who have used the system the majority received their information by print media – Green Vine and newspaper. It might be possible to increase the use of NAMIS by re-examining the information dissemination methods, since most farmers do not appear to use the more modern ICTs dissemination methods. Educational level, decision making responsibility and farm size based on this study influences the use of NAMIS. Age and gender did not have an influence on the use of NAMIS. The use of NAMIS and by extension other MIS in the region might be increased by improving the educational level of our farmers as is suggested from the findings of this study. As other Caribbean countries attempt to adopt NAMIS or versions of it I will recommend that a cost benefit analysis is undertaken, especially of the various means of disseminating information. Generally, dissemination of market Chogou, P.L., P. Lebailly, A. Adegbidi, and E. Gandonou. 2009. “Impact of Public Market Information System (PMIS) on Farmers Food Marketing Decisions: Case of Benin”. Paper delivered at 111 EAAE-IAAE Seminar ‘Small Farms: decline or persistence’ University of Kent, Canterbury, UK, 26 – 29 June 2009. Irick, M. L. 2008. “Task-Technology Fit and Information Systems Effectiveness”, Journal of Knowledge Management Practice 9(3). Khalil, J. and C. Kenny. 2008. “The next decade of ICT development: access, applications, and the forces of convergence.” Information Technologies and International Development 4(3): 1 – 6. Parikh, T. S., N. Patel, and Y. Schwartzman. 2007, “A Survey of Information Systems Reaching Small Producers in Global Agricultural Value Chains.” In Proceedings of IEEE Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Development (ICTD) 2007, 334 – 344. Agri-food Value Chain Verdouw, C. N., A.J.M. Beulens, J.H. Trienekens and S. Wolfert. 2010. “Business Process Modelling in Demand-Driven Agri-Food Supply Chains.” Proceedings of the 4th International European Forum on 6 System Dynamics and Innovation in Food Networks. Organized by the International Center for Food Chain and Network Research, University of Bonn, Germany. Agri-food Value Chain 7 Table 1: Information dissemination method by group Information dissemination method Person to person Percent 9 18 Print media ICTs 73 Table 2:Farm size and use or non-use of NAMIS Used NAMIS 221 9.01 Farmers Mean farm size (acres) Did not use NAMIS 281 5.21 Table 3:Decision maker of farm and use or non-use of NAMIS Main decision maker (yes) Main decision maker (no) Used NAMIS 207 13 Did not use NAMIS 249 32 Table 4:Educational level of farmer and use or non-use of NAMIS No formal educational level Primary school started Primary school completed Secondary school started Secondary school completed Tertiary level education Used NAMIS 0 10 48 36 88 15 Did not use NAMIS 2 51 105 50 53 12 Table 5: Decision maker of farm and use or non-use of NAMIS Males Females Used NAMIS 199 24 Did not use NAMIS 251 28 Table 6: Age of farmer and use or non-use of NAMIS Under 25 years 25 to 34 years 35 to 44 years 45 to 54 years 55 to 64 years Over 65 years Used NAMIS 9 36 75 71 24 9 Did not use NAMIS 8 48 71 96 52 13 Agri-food Value Chain 8 Table 7: Percent of respondents receiving information from the various NAMIS Information source Percent of respondents 68 Green Vine Newspaper (market watch) NAMDEVCO’s staff Telephone Website Kiosk Email Fax 58 57 13 12 10 1 0 NB: There were 225 respondents sources