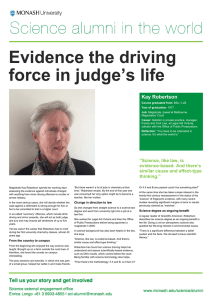

Robertson Foundation lawsuit Q&A

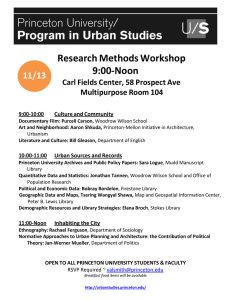

advertisement