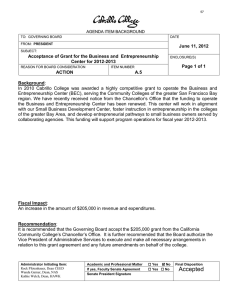

Entrepreneurship in Public Colleges and Universities

advertisement

Entrepreneurship in Public Colleges and Universities Baron Perlman - U. Wisconsin Oshkosh Institutions of higher education in the United States are integral to our society's well being, the envy of the world, while at the same time chastised for not performing as well as they should. They must be managed well, especially if new ideas are to be implemented and flourish. Many would consider institutions of higher education to be the future of our society. Despite facing complicated environments and difficult times, there is no reason that organizational entrepreneurship cannot be successful in higher education. Think about it. Since colleges and universities seldom merge, seldom go out of business, and seldom are acquired, how are they to maintain their vitality? One answer is organizational entrepreneurship, intrapreneurship (Pinchot, 1985) as it also is called. Overview of Entrepreneurship in Academe This presentation presents a brief overview of entrepreneurship in academe, with an emphasis on the academic internal environment the working world of academic entrepreneurs. While corporate efforts in intrapreneurship have important lessons for colleges and universities I argue that the obverse also is true; that lessons from academic intrapreneurship are applicable and valuable to other settings and efforts. It was and is true that institutions of higher education cannot wait for public policy before moving forward, and that public institutions cannot wait for tax dollars to institute new, and maintain quality existing programs. In Wisconsin the UW System was first called “state supported,” then “state assisted,” and now wags are talking about its colleges and universities being “state located.” 2 We know that service organizations must be manageable, because some seem successful. And if they are successful, intrapreneurship must be partially responsible. Drucker (1973, 1985) supports the idea that colleges and universities need to be entrepreneurial and innovative. But they are curious organizations and need to be well understood by entrepreneurs. They have multiple constituencies, long-standing organizational structures, employees with lifetime employment, and to say the least, “unique” decisions making processes. And they have many subgroups, more than most organizations, bound together in a common goal of finding a parking place. But the work is probably no more difficult for the organizational entrepreneur than in other organizations. Money is available, despite what people say. What other organizations attempt to get all the funds they can, and only get more if they spend every cent of it. Exist and the money will come is probably accurate. The Intrapreneur’s World Leadership Any organizational entrepreneurship team must have leadership. The common wisdom in academe is that most faculty will not follow someone if the change he or she is proposing is higher than the height of stepping from the street to the sidewalk, that is, the height of a curb. It is finding ways that are at least neutral, or more positively of interest to faculty, where leadership becomes so important. It is important to emphasize that even in academe, where teaching, learning, scholarship and service have been the pillars of the academic community for centuries, there is a need for path finding. We teach in new ways, in new programs, with new sources of support and funding. Our 3 institutions change their goals, and with these changes come opportunity for new programs and intrapreneurship. Leadership also involves the discerning ability to strike to the heart of the matter, to clear away the fluff and arrive at reality. Of course you know that leadership involves vision, asking what an institution or program or department might become. But vision is more than the intellectual, it involves the affective realm. For you cannot be a leader unless others follow you. And if they are to follow you, they must believe. And that vision must be effective – it must be doable. Often it is the Chancellor or Provost who provides the ineffective vision, the grand idea that resonates within the ivy-covered walls. It is the entrepreneur who makes that vision effective and determines ways to make it into a reality. If I were to add one more ingredient to leadership I would add “trust and integrity.” Always tell the truth, tell the full truth, and tell it before you are asked. People and their Empowerment It is people who help you successfully complete an entrepreneurial project, and it is people who will use it. Think of a college and university. Even if most of the faculty could not survive outside of academe they are bright, many are good at what they do, most have PhDs, and most work extremely hard. Intrapreneurs need to understand the organizations in which they work. Faculty may be bright and well educated, but their needs to be appreciated are probably no better managed than others’. They need to count and be counted, they want to be heard, and they want to be able to do the job they have to do, even if each faculty defines that job differently for himself or herself. I am not talking about absolute power 4 via empowerment – that is a perversion of the concept. If vision can be effective and make something useful happen, then empowerment is the process by which that goal is achieved. That process implies information, resources (money, support staff, time), and support. It may be rare when administrators talk, really listen, and really, really understand what their faculty tells them. Advances in academe are probably equally made over the dead bodies of faculty and administrators. But they are made. What occurred at UWO Oshkosh, occurred because of the faculty, not despite it. Entrepreneurship, empowerment, and successful innovation involve learning. Yet I am constantly surprised how little most faculty know about how a college or university works, its budget and how much is discretionary or fixed costs, demands from boards of directors or regents, what is negotiable and what is not, and so forth. But if faculty are taught what is important – accountability in forms that bean counters and politicians can understand that meet the needs of multiple constituencies, visibility in ways that enhance administrative careers while adding to the value and quality of an undergraduate or graduate education – they are quick to see the implications for change and innovation. For example, it is my conclusion that much of what passes for academic strategic planning that supposedly involves the entire academic community, and I am finishing my 4th or 5th, is doomed to outright failure or mediocrity because faculty are not given full information and can never be full participants in the process. Academic Cultures Culture is unseen, highly influential, difficult to change, but impossible to ignore. It affects our perceptions, desires, goals, actions and feelings. Doing entrepreneurship in organizations means developing a high awareness for the various cultures one 5 encounters. Culture is shared meaning. Is your college or university really a high school in how it behaves and in what it values? Does it aspire to greatness because of its symbols and culture? Is the culture one of “beware,” “be careful,” “be bold,” or perhaps most interesting, “be both bold and beware,” the proverbial blinking yellow light. You begin to understand culture when you look at the heroes of an organization. Ah, you say, your college or university has no heroes. Isn’t that interesting. You look at the myths if there are any. You look at the symbols, the golden dome of Notre Dame, the quad where once walked the Nobel Prize winner. What metaphor best describes your institution? If it is a military army, then entrepreneurial efforts will be very different than a plodding giant, or the turtle (last in for everything but with beliefs that to the slow go the spoils). Is yours a fairy tale organization where good triumphs over evil and students and faculty live happily ever after? The decisions, strategies, and allocation of resources are affected by culture. Does your institution have any rites or rituals? Mine has an opening-day coffee and donuts all-faculty meeting over which the Chancellor presides. This meeting is a vestige of our teaching college past, and communicates powerful information about what we are, or at least once were. The problem is that our culture is not one of “one big happy community,” although we pretend to be so. It is the pretending that is more important and more influential. Look at your commencement, convocations, new student week, colloquia and so forth and you will begin to get insights into an institution’s culture. I mentioned our opening day meeting, a vestige of a truly simpler time at our institution. The past, even though we think it is gone, influences the present. I work with 6 faculty who were hired 35 years ago when promises were made and broken. They see the same today. Entrepreneurs need to know and understand the past. Organizational System Variables There are several academic “system” variables to which any organizational entrepreneur must understand and attend to. Rewards. I believe that rewards are the most important of these variables. The three most powerful rewards I have observed in academe are (a) money, (b) time, and (c) an intrinsic feeling of a job well done. It is curious that money should be so powerful in academe, a setting many professionals choose to work in where they are paid less than in the private, non-academic sector. But competition is fierce for both salary and other scarce fiscal resources. Never underestimate the power of money in what you can offer a member of your entrepreneurial team, or if your project is developing a new program or process on campus, whether users will be compensated in some way. But unlike some other settings I think that time is equally important to most academics. If they are not paid what counterparts make in the private sector, and have no opportunities for bonuses, corner offices, private parking places, and other perks, at least they treasure the illusion that the can use their time as they choose. I say illusion because once one parcels out teaching, service, and other responsibilities, there is not a lot of discretionary time left for reading, scholarship and the like. And given many faculty members’ needs to achieve, know, and master, they often take on too much at any one time. Any entrepreneurial project on a college and university has a much better chance of success if it values faculty members’ time. 7 There also is the reward of allowing faculty to participate in something that is interesting. Many outside academe have no idea how boring a lot of what faculty do really is. If your entrepreneurial project is one that has substance, might make a difference, and requires some effort, faculty might be really interested. As a senior faculty I have given up some of my “run of the mill service” and I am surprised how infrequently ad hoc groups are needed to get something substantive done. Technology and bureaucracy. Let me mention two other dimensions of academia, often needed if a new idea is to see the light of day. One is technology. Here I am using technology as people usually think of it, computers and the like. Techies in computer services may be largely unseen until the machine in your office crashes, but they often know a great deal about how to keep track of faculty, what data bases are available, and what constraints exist to the accountability and tracking that may be a necessary part of any grant proposal or enactment of an entrepreneurial idea. You need to cultivate and get to know the techies on your campus. The second is bureaucracy that can block implementation of new ideas fairly easily. You need to make your institution’s bureaucracy personal and friendly to your ideas. Get to know people and learn what they do. Faculties often times are not familiar with the numerous offices and people in administration. You have to be. Institutional-Wide Entrepreneurship: A Case Study I begin with the power of metaphor. If I can leave you with any message today it is to conceptualize and think of your entrepreneurship within organizations from a perspective and within a framework different from what you are really doing. I believe that we think best when we use language other than the “technical” language of our 8 discipline. This is why best selling management books are about Attila the Hun or “Herding Cats.” Metaphors free us, are powerful, enable us to think more abstractly, and more critically than other ways of thinking. Metaphors open doors to new and better ideas. My university in the early 1970s was dying. It had falling enrollments, was trapped in its normal school past, and was unable to adjust to new presents and futures. It was losing its resource base. Projections looked bleak. There were tenured faculty layoffs, a process that some 30 years latter still have negative and unanticipated repercussions for the institution. There was a lack of confidence in administration. We needed leadership. We had become an albatross to System Administration, a Red Cross University in need of ministry. Educational Testing Service from Princeton administered two new research instruments about our functioning and institutional goals. We scored the lowest in the country. No one wants to publish or discuss the results. What we needed were more and better students. What we also needed was a faculty with some confidence in administration, some pride in what they did, and even though they were tenured, a feeling that they would not be fired. How does one think of a dying university in ways that point the way to a more productive and vibrant future? The metaphor that seemed to have the most power and explanatory power was one of druids. Druids are the keeper of knowledge and they behave in different ways in colleges and universities depending on the health and culture of their institution. In our university the faculty druids were deep in the forest. There was no reason to come to where the sun shone; there was no sunlight. So the most productive druids, the faculty 9 who did the best teaching and the best research simply faded away. They had little or no time for politics. If their forest was dying, they would go about what they did best – creating, teaching, and preserving knowledge. Druids (faculty) become interested in ideas if these ideas have substance and merit In other words, band-aids, administrative jargon, and face validity won’t solve the problem. Our administrators pushed a general education program to have new teaching methods and new toys. Administrators tell the druids that “we have the money why don’t you come teach in this enlightened fashion? The program will raise our enrollments.” The druids watch from deep within the forest, the program will soon die. A new Chancellor is hired. The druids stay deep in the forest. He asks to be called Bob. Interestingly he is not a druid but he seems to know, respect and like druids (administrators who do these things are rare). He understands that druids want to work in universities, not in institutions of higher education that act like high schools. He isn’t on campus a month and announces that the library’s hours have been extended. The druids are curious. He makes decisions and is clear about what he likes and does not like, and ignores the rest. He will not be all things to all people. The druids are still curious. He can poke fun, his dog becomes an “Outstanding Educator” and the story makes the Chronicle of Higher Education. Druids like to laugh, they are a bit more curious. Some local banks will not participate in a new federal student loan program. The chancellor switches university accounts to those that will. The druids become more interested. Is he showing courage or stupidity? The druids don’t care; either has potential. Fiscal problems continue. The Chancellor argues with System that fiscal 10 emergencies not be declared. He sees himself as a steward for the forest and will be responsible for its health. The druids watch and wait. No layoffs, some druids smile. In any university there is always discretionary money – always. The chancellor listens to his deans and supports some druid initiatives. Some bad decisions are made. The chancellor fires people. He will lead the parade; he will tend to the forest – the druid’s forest. He realizes he is a caretaker. He will leave but many druids will spend a lifetime in this particular forest. He presents his ideas to the druids. The new university will revolve around individual choice (new calendar, student and faculty decisions on types of courses and when they are offered, and concepts of time). He views time as a technology to be massaged, used, controlled, and won over. He promises the druids some flexibility in their work worlds – when they will teach. He is honest that the 12-credit teaching load will continue. But…. faculty will be able to free up blocks of time for their druid work. He knows how important druids are to a university (administrators who act as if this is true are rare). He is proposing flex professional time. The druids have to work a bit to make sense of his ideas. They like this. He tells the druids there is not enough professional time and his ideas will help them batch time so they can use it better. Druids like blocks of time to devote to their ideas. He talks about the need for druids to be supported in their professional development. He is, in essence, proposing a new tradition on campus. Druids will be able to get money and time to do druid-like things. The druids have put up with a lot of ambiguity, some urge the chancellor to change the forest and get on with it. He does. He submits 12 grant proposals to FIPSE, more than have been submitted in total in the 11 last 25 years since he left. He takes $200,000 and puts it in a fund to initially support faculty development. The druids now are very very curious. An administrator who puts money where his mouth is – he may be able to protect the forest. He has moved the druids from being traditional faculty into druid entrepreneurs. They can teach in summer as part of load and do their work during a regular semester. They can teach 7-, 10-, 14- or 3-week classes. They can get release time for their work, money, or both. And they decide who the successful druids are, not administrators. It is druids who will make up the faculty development board that oversees all funding decisions. And perhaps most importantly, the chancellor’s change agent, a former druid himself (physicist) will serve on the board and teach the druids how to do the job right. It is an ongoing theme in my presentation that most faculty fail at new initiatives on their campuses because they do not know what they are doing, which is not their fault. They simply never are taught how a university works, the rhythms of the administrative side of the house. He will teach them. I want to pause now and perhaps point out the obvious. The metaphor of faculty as druids has more explanatory power and is more useful than talking about faculty directly. Administrators have to make deals with druids; it is the productive, vibrant faculty who are needed to support any administrative initiative. The druids felt supported. They felt that Oshkosh had become a good place for them because administrators understood and supported druid work. And they came to learn that no other university in the country cares for its druids with a development program the way that Oshkosh did and does. 12 Postscript The new calendar has two 14-week semesters that can be divided into two seven-week periods, and two three-week interim periods. Summer school becomes two four-week sessions or eight-week sessions. Faculty have much more flexibility in how they work. Class periods are extended from 50 to 60 minutes, 12 credits can be taught in 14 weeks instead of 17. The three-week interims now can be used for teaching if faculty want, or for research and service. Faculty also can develop an “annual contract.” They can batch their time anyway they choose to equal 24 credits of teaching if it does not harm program and course array. They also can develop a two-year contract, teaching more or less in one year or the other. In other words, their obligations are unchanged; their flexibility is increased. To achieve these things the faculty gave up money. Summer school used to pay 11.1% of a base salary; it is lowered to 7.5%. The druids would rather do scholarship and have flexibility in their use of time as compared with a few more dollars. But try to sell that reality to faculty directly. The entire investment and changes means that over 90% of the faculty have participated in the development program. The University’s capabilities were increased. Increasing the “carrying capacity” of a college or university is rare. To this day, all major elements of the innovation, including the comprehensive Faculty Development program, and the calendar, continue to function. 13 Understanding the Organizational Entrepreneurship The change was organizational wide, involving almost every aspect of the university. It used new technology well: time, computers, the calendar, and faculty development. In brief, the changes were a paradigm shift in academic functioning. I present a variety of variables that affect any entrepreneurship in an organization. In our case they all came into confluence at once, providing the foundation for a successful effort. The Past. The time was ripe for change. The University was both under duress and it was 103 years old without a single positive symbol. The past was no longer productive in the present. External Environment. Students were no longer flocking to the university. The need for education existed; we were simply not meeting it. The decline in enrollment was not predicted. Consequences were declining budget, faculty layoffs, and scrutiny from UW System. Organizational Decision Making and Strategy. Decision-making was top-down but not suited to what needed to be done. The organization had no strategy to deal with its new realities. It was not doing the right things, nor doing anything well (ineffective and inefficient). Organizational Variables. These variables were strongly anchored in the university’s past but not terribly effective: structure was traditional, the bureaucracy was process-oriented, rewards were not based on meritorious behavior and much such behavior went unrewarded, communication was limited and closed, obtaining new members was limited, the budget was falling, there 14 was ineffective scanning of the environment. Technology was not used effectively. There was a leadership vacuum. The Entrepreneurial Environment. UW System wanted change and the major charge for the new chancellor was change. This is an unusual selection criterion. He acted rapidly to avoid being caught up in the status quo past. He supported change and put the green light on. The calendar plan provided the framework for change presented as the University of Alternatives. The slogan disappeared quickly; the changes persevered. The chancellor needed the creativity and energy of his faculty and administrators; he was well positioned to sponsor change. The environment strongly supported entrepreneurial efforts. There was crisis and incongruity – how could an institution over 100 years old be dying, but it was. One key to change was empowering faculty by their presence on numerous committees. Also those doing the hard work of change were provided with information, support and resources. Affectively faculty felt significant and as if they were engaged in important business near the heart of things (they were). Time as Technology. Timekeeping and its management can be conceptualized as technology. The best example is “batched” versus “real” time. In most colleges and universities time is “batched.” Classes start and stop at rigid, infrequent points in the calendar. There is a lot of waiting. The same is true for registration, when enrollment is counted, when faculty begin and end their contractual year and so forth. 15 What UW Oshkosh moved to was “real” time. Tasks are attended to when they arise; they are not collected and acted on at distant intervals. Airlines and the stock market are examples of real time. The world faculty interact with is moving toward real time: conferences and professional opportunities, when ideas strike and must be acted on, being asked to collaborate or write a book chapter. And of course teaching requires most faculty to batch their good ideas and time and work on them outside of the teaching regimen. o Need a class – find one in a second 7 week or 3 week interim schedule. o Want time to do scholarship – put together a two-year plan and create real time for your work. o Submit a proposal to faculty develop – have it pre-reviewed anytime during the year and get feedback in real time (decisions on such proposals were in batch time – twice a year). Want to get other proposals funded (going off-campus, bringing an expert speaker to campus – submit and receive feedback 12 months/year. UW Oshkosh tried to restructure time with more choices for both students and faculty. Bullpen registration was replaced with one of the first on-line registration systems in the country. Information technologies were highly involved with creating a reporting system that could manage real time in the university. o UW System had to be educated that by counting new students the third week of fall semester, the University was receiving less funds than it should since some students were starting the second 7-weeks of the fall, or in the January 3-week interim. 16 o Keeping track of when faculty was on load was difficult. Faculty could arrange an acceptable work schedule in many ways over a two-year time period. Problems of payroll were paramount. You always need techies. Administrators were concerned with monitoring, control and accountability. The intrapreneurs were concerned that faculty understand the decision options available to them. Culture. The culture at UW Oshkosh before intrapreneurship was daunting status quo. It was a paternalistic time and ignorance was bliss. There was no culture of meritocracy. The university needed a new culture, one emphasizing expert power what you know and can do is most important. The Faculty Development Program established expert power; to this day it has more resources to give faculty than the deans of the university’s four colleges combined because it knows druids and treats them expertly. The Faculty Development committee, chaired by the chancellor’s major change agent for 7 years, adopted the following culture to guide its decisions and to apply to its druid-colleagues. o Optimism about a university that was professional and expert. o A long-term view. o A clear vision. They knew what an expert culture would be like. They valued professional development rather than political action. o A clearly defined and an important agenda. 17 o A trust of faculty. When in doubt, “fund someone.” When in doubt, “trust faculty to do what they say they will do.” Ignore personalities and focus on the professional development potential of any faculty idea or proposal. o Trust and integrity. Follow the rules and be above board o Communication. Let people know what you are doing and why. Codify, put it all in writing. Be predictable. o Provide for continuity. Train new board members; get druids to serve. Lessons Learned The intrapreneurial effort is now the university status quo. Why did this effort succeed? What lessons can we learn from what went on? Leadership and Empowerment These are necessarily and require great effort. But they are not ends in and of themselves. It is a trap to think that they are all that is necessary. Leadership and empowerment are a means to an end, not the end goal itself. Commitment and Community You need an end product, in our case a new calendar and faculty development system that endure over time. To that end, you need commitment and a collective feeling of acting for the greater good. In our case the chancellor was trying to insure the health of the university and do away with more tenure layoffs. The events had purpose and meaning. This is where metaphors are so important. They assist organizational entrepreneurs in communicating the importance of meaning in what they are doing to others. 18 Efficiency and Effectiveness Both are necessary. A new calendar, a faculty development program, and on-line registration were instituted because they were good ideas. But being good ideas is not sufficient. They have to be manageable. Students’ registration reports, accountability of faculty time, integrating faculty development payments into the university’s payroll system all had to be doable, or the intrapreneurship would have failed. Efficiency also implies a budget that can sustain the new effort, standing up to detailed audits (the “tight” side of new programs), and by anticipating what others need to know and providing it to them. Why Not? Organizational entrepreneurship involves fatigue, deadlines, failures, and great pressure. One has to avoid the temptation to succumb, and become traditional oneself. Everyone wants his or her fair share or more, everyone manipulates. You have to keep sight of what can be but at the same time be a realist. That is very hard work. Relentless Dedication There is always something to do, people with whom to talk, details one has not anticipated taking care of. You have to keep at it. There are some ways to survive, however. Always Write It Down. Define reality as you know it and write it down. A written source of ideas, memos of understanding and the like can be read and reread, and tie down loose ends. Written documents also involve constituents in compromise, interaction and commitment. It structures what is being down and is “real.” It also helps intrapreneurs differentiate between tinkering and substance ideas and action. 19 Always Follow Through. To be trusted and credible you need to keep track of what you promise and whom you say you will get back to, and do so. This is leadership; your words have to be good. If you say you will do something, do it. Keep obsessive track of your interactions and transactions, and let people know what they need to know, even if the answer is “no.” Trust Trust is the lubricant of entrepreneurial work. Once it is gone, things grind to a halt. Aside from superb communication and following through, there are other ways to maximize trust. No Inside Trading. Members of an intrapreneurial team have information, contacts, and sometimes resources others in the organization do not. Never feather your own next with these. You cannot be perceived as benefiting except as the formal organizational reward system will treat you. Don’t Fight in Public, Pettiness Does Not Count. Keep focused on your goals. There is little purpose in publicly taking people to task. There is almost no instance where public name-calling or battles can be productive. Handle things professionally. What Is, Is. Some things just are. Sometimes there is no deep or hidden truth. Some times there is nothing you can do. For example, you can’t change something without changing it. Organizational entrepreneurship is a process of change. This is why there is so much chaos and known attached to any such project. A second example illumines this point: You can’t give up control without giving up control. If you empower, do so. You cannot delegate autonomy. Either others are responsible or they are not. 20 You Cannot Be a Bleeding Heart and an Intrapreneur There are always losers. People may not be positively affected by change. You cannot be sensitive to the individual plight of everyone in the organization. For some faculty, less money for teaching summer school was a great loss. For those who had spent long hours devising the best possible 17-week course, the new calendar forced them to redo these courses to a 14-week semester. For those faculty who prized the traditional registration process and control who entered their classes, the changes were devastating. Academia is not Unique Nothing I have talked about is unique to a public institution of higher education. Intrapreneurship is not more difficult or easier in other organizations. Vision is Not Necessary The intrapreneur does not need a clear vision of the future. It is not an absolutely necessary ingredient. You can lead by vision or by direction. In many cases the latter is what happens. You need to know what direction you are heading towards, not the exact specifics of the promised land (even Moses never saw the promised land). Failures Occur Getting “beat up” and failing builds wisdom, not merely success. One cannot be a good intrapreneur without failing. Our new calendar is a relative failure. Not as many faculty use non-14-week courses as was hoped. The Calendar has not fostered the innovative programs it might have. It has not attracted the number of part-time, older students it promised it would. But it was a resounding success in unfreezing the 21 university, empowering the faculty, institution of faculty development, and modernizing registration and the faculty personnel database. Faculty Development is wildly successful but has its failures. Some of its components are seldom used. The culture of empowering faculty did not generalize to other areas of the university. There was no special group to oversee the calendar or curricular decisions that were innovative. Expert decision making in relationship to the curriculum never developed. Conclusion It was a heck of a ride, perhaps the only saga senior faculty can tell about our institution. Who knows when the next confluence of need, leadership, and the right people will come along? If you are in the midst of organizational entrepreneurship, treasure the moment. Regardless of the outcome, it seldom gets that good. 22 References and Recommended Readings Drucker, P. (1973). Managing the public service institution. The Public Interest, 33(3), 43-60. Drucker, P. (1985). Innovation and entrepreneurship: Practices and principles. New York: Harper & Row. Perlman, B., Gueths, J., & Weber, D. A. (1988). The academic intrapreneur: Strategy, innovation, and management in higher education. Westport, CN: Praeger. Pinchot, G. III. (1985). Intrapreneurship. New York: Harper and row.