Consequentialist Options

advertisement

Consequentialist Options

1. Act-consequentialism (AC) is a combination of two elements. According to the

first axiological element, when an agent faces a set of options, they can be ranked in

virtue of how good their consequences are. According to second deontic element, an

act is right if and only if it is an option that is evaluated as one of the best in the

previous ranking.

According to a classic objection, this view fails to leave sufficient room for

moral freedom. As I am currently writing this paper, I could continue doing so, go

out for a walk, meet my friends, travel to France, and so on. None of these actions

would be morally wrong, other things being equal. Yet, according to AC, these

options are permissible only if none of the other options have better consequences.

All the abovementioned options could then be morally right only if they each had

equally best consequences.

However, it does not seem likely that this could be the case. Considerations

such as pleasure, knowledge, aesthetic enjoyment, biodiversity, and so on can make

the consequences of actions good. Whichever options we compare, it seems that

there must be a difference in how much of these goods the options will bring about.

That a whole range of options would bring about an equal amount of these goods

would be a cosmic coincidence. As a result, simple act-consequentialism seems

unable to accommodate the intuitive moral options.

This appearance is mistaken, or so I will argue. Consequentialism can

provide far more morally permissible options than previously thought.

1

2. Consequentialist responses to the freedom-objection fall into three categories. The

first response is denial. It is claimed that, on this issue, our common-sense morality

is mistaken. The options it permits do not bring about most value to the world. But,

to bring about less value than possible would be ‘profoundly irrational’ (Pettit 1984,

172), and therefore wrong. Thus, on this view, the actions that seem optional to us

are really impermissible.

This rejection of the intuitive options can be made more appealing. It can

be argued that our moral intuitions should be disregarded unless they can be

vindicated by a consistent moral theory. It can then be claimed that any theory

which recognises moral options would be internally inconsistent (Kagan 1989, 19–

42). If this were the case, the act-consequentialist could claim that we should ignore

our intuitions about the options.

It could also be argue that there is a difference between act’s wrongness

and the agent being criticisable for it. Some suboptimal actions (which intuitively

are permissible) could be morally wrong actions for which agents are not

condemnable (Pettit 1996, 164–8). This would mean that no harm is done by calling

them wrong. I have no objection to these strategies, except that, if my argument

below is right, then they are based on mistaken view about how many options

consequentialism creates.

The second set of responses tries to make room for options by revising the deontic

element of consequentialism. Some have tried to add an explicit permission to

pursue some sub-optimal outcomes in addition to the optimal ones. This is called as

the hybrid view (Scheffler 1982). One is permitted to bring about suboptimal

outcomes when the optimal outcomes would require sacrificing one’s own important

2

projects and commitments. Such permissions can be motivated by the need to

protect the integrity of agents. Again, this strategy to revise consequentialism seems

to be unmotivated if it can be shown that consequentialism itself creates enough

options. This is what I hope to show below.

There is also another way of revising the deontic element of actconsequentialism to accommodate options. This response is a view called satisficing

act-consequentialism (Slote 1982). On this view, right actions have ‘good enough’

consequences. One is free to choose any action such that either (i) the value of its

consequences does not fall below a certain threshold, or (ii) the value of the

consequences is reasonably close to the value of the best consequences. The hope is

that most intuitive moral options satisfy these criteria.

Unfortunately, satisficing act-consequentialism provides wrong kind of

options (Bradley 2006). In some cases, an agent will be able to bring about enough

value by either harming some people or by actively preventing more value to be

brought about. Under the satisficing views, these actions would be permissible

options. Having to say this is a high of a price for the intuitive options.

The third possible responses to the freedom objection try to save the intuitive moral

options by concentrating on the axiological element of consequentialism.

I have assumed so far that the axiology of AC is complete and finegrained. This means that evaluative ties between outcomes and cases where their

value is incomparable are rare. An act-consequentialist could reject these

assumptions. If value of the outcomes was a coarse-grained and incomparable

matter, then there could often be many optional actions such that they would not

have alternatives with better consequences (Vallentyne 2006, 26).

3

This move would fail to save all the intuitive moral options. For each one

of the evaluative properties, there will a distinct set of basic properties in virtue of

which things have that evaluative property. The cases in which actions have these

basic properties to different degrees will be problematic for the considered view.

It seems plausible that the consequences of actions have one sort of value

in virtue of the pleasure they contain. Now, it is permissible for me to watch

television for either 45 or 60 minutes, other things being equal. As a result, I would

experience, say, either 9 or 12 units of pleasure when there are no other relevant

differences between the outcomes. In order to say that both of these actions are

permissible, the act-consequentialist under discussion would have to say that neither

of these outcomes is better than the other.

This could not be because the value of the two outcomes is incomparable.

The situation is such that the only difference between the outcomes is the amount of

one basic property that gives rise to only one kind of value. It must be comparable

how much that value the outcomes have. So, the defender of the view would have to

claim implausibly that the outcomes have an equal amount of that value. If pleasure

makes outcomes good, the additional 3 units of pleasure must make the other

outcome better than the other. For this reason, a coarse-grained and incomplete

axiology will not be able to save all the intuitive moral options.

Another form of act-consequentialism tries to accommodate moral options by

relying on many evaluative rankings (Portmore 2003). According to Portmore’s

dual-ranking proposal, we can rank the consequences of the agent’s options from

her perspective in terms of both moral and all-things-considered value.

4

For instance, saving a child from a burning building whilst risking one’s

life may bring about states of affairs that are from one’s perspective morally

speaking the best but not the best all-things-considered. This is because potential

losses in one’s own well-being do not make resulting states of affairs morally worse

from one’s perspective. Yet, these losses make the same consequences worse allthings-considered.

Portmore claims that an action is permissible if and only if it does not have

an alternative that would bring about more of both moral and all-things-considered

value from one’s perspective. This explains why it is permissible both to save the

child and not to do so. Neither one of these options have an alternative that would

have more of both moral and all-things-considered value.

Portmore’s proposal faces a problem when we consider basic actions that

are suboptimal on both accounts. Some of these actions are permissible options.

Think of watching your television either for 45 or 60 minutes with a friend of yours.

She is made happier by the first option but even more so by the second option. The

happier you make your friend the better the resulting outcome is morally from your

perspective. You will also be happier the happier your friend is. Thus, watching

television with your friend for 60 minutes would also be better all-things-considered.

In this situation, according to Portmore’s dual-ranking view, it would not

be permissible watch your television with your friend for only 45 minutes. You have

an option that brings about more of both moral and all-things-considered value.

However, our common-sense morality would permit this. This makes me think that

all the previous proposals to respond to the freedom-objection are either mistaken

about how many options consequentialism creates or problematic in some other

way.

5

3. I want to then explain how whether an agent is required to do some action or

permitted to choose it from many permissible options can affect how much value the

consequences of that action have. Furthermore, I want to claim that the fact that an

agent is permitted choose some action out of many permissible options can make the

consequences of that action better in three ways (Dworkin 1988, 78–80).

The consequences of an action having been chosen from many permissible

options would have instrumental value if the action would bring about, as a result of

having been chosen from many permissible options, other things which are

intrinsically good. First, it could be claimed that individuals want to be able to

choose between different permissible options and they find making such choices

satisfying and pleasurable.

Being able to choose an action from many permissible options can also

enable us to learn things about ourselves. If one wants to know whether one is

courageous or cowardly, one can do so only by seeing what kind of choices out of

many permissible options one makes in certain kind of situations of risk. If one

were always required to choose some particular action in the relevant kind of riskscenarios, then there would not be room for the type of practical deliberation in

those situations that is required for acquiring self-knowledge about one’s character.

It could also be argued that the fact that an act can be chose from many

permissible options has intrinsic value as such. Being able to choose to do an action

out of many permissible options would in this case be desirable for its own sake. If

this were true, the same action would bring about more value when one can choose

to do the action from many permissible options.

6

This is because one of the

consequences of the action in that situation would be that an intrinsically valuable

choice out of many options took place before the agent did the action.

The consequences of an action that is done after a choice between many

permissible options can also have constitutive value. The idea here is that choices

between many permissible options can be in part constitutive of larger, more

complex wholes which can have intrinsic value.

Some choices out of many permissible options have ‘representative value’

in this way (Scanlon 1988, 252). If a poet writes a poem, the value of the outcome

does not solely depend on the poem’s aesthetic qualities or on how much the

audience appreciates it. The same poem could have been randomly generated by a

computer. Yet, in that scenario, the existence of this poem would not be equally

good.

The poem gets additional significance from the fact that the poet chose the

words out of many permissible options to express her beliefs, desires, and emotions.

The poem, as a result of the prior choices between many permissible options, comes

to represent the poet’s thoughts. The poem is now a part of a more complex whole

which includes the poet’s thoughts, the world which these thoughts represent, and

the audience’s appreciation of the poem as a representation of the world. This

complex whole has intrinsic value, and therefore the poem has constitutive value.

Choices between many permissible options can also have constitutive

value called ‘symbolic value’ (Scanlon 1998, 253). We intuitively take otherwise

similar outcomes to be better if they result from our choices between many

permissible options. This is easiest to see in the case of one’s own actions. I would

value my career, friends, and house considerably less if they had been chosen for me

instead of having resulted from my choices between many permissible options.

7

They all would be much less valuable if they were a result of a strict path chosen for

me by someone else. Thus, choices between permissible options as such can make

things better.

Why would this be? Compare the situation where we are free to make all

these choices between many permissible options to the one in which others would be

making the same choices for us. The removal of our ability to choose between many

permissible options can be understood as a judgment that we are incapable of

making reasonable choices ourselves. Granting someone a freedom to choose from

many permissible options is thus a way of recognising her abilities to make

decisions.

One could then argue that this kind of recognition of our rational

faculties is an intrinsically valuable whole, and that having a choice between many

permissible options is a constitutive part of this whole. This is another reason why

choices between many permissible options could have constitutive value, and why

having a free choice to do a given action can itself create more value to the world.

In the following, I will assume that choices between permissible options

can have value in all these ways.

4. My proposal based on the previous assumption about the value of choices begins

from the thesis that a consequentialist has good reasons, on purely consequentialist

grounds, to accept that some sub-optimal action is a morally permissible option for

an agent when it is better that the agent has an option to do this sub-optimal action,

whichever permissible action she ends up doing. If a sub-optimal action A is such

that, even if the agent ends up performing that action, things are better than if she

performed some other permissible action without A being an option, then it makes

8

sense for the consequentialist to accept that A is a permissible option for the agent.

After all, that A is a permissible option can make things better in this situation.

This account can be formalised in the following way. Assume that an agent

could only do either action A1, or A2, or …, or Ax. Each one of these actions would

have some definitive consequences when there was a requirement to do it. Let us

assume that A1 would have the best consequences if the agent were required to do it,

A2 would have the second best consequences if the agent were required to do it, and

so on.

Let us use curly brackets for alternative sets of permissible actions. So, if

the agent would be free to choose between A1 and A2 her option-set would be {1, 2},

if the agent would be free to choose between A1, A2, and A3 her option-set would be

{1, 2, 3}, and so on. My proposal then is:

Consequentialist Options: An action An is a permissible option just in case

the value of the consequences of An given the option-set {1, ... , n} is at least

as great as the value of the consequences of An-1 given the option-set {1, …, n1} where An-1 is the least optimal action in {1, …, n-1}.

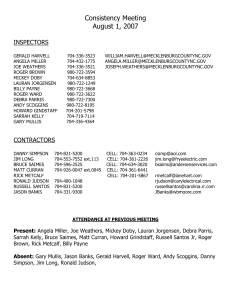

To see how this proposal works in, let us assume that the table below represents the

actions which Jill could choose to do and the value of their consequences.

Action

A1

Charity-work

Value of consequences when

required

200u

A2

Go to Paris

150u

210u

A3

Visit parents

100u

215u

…

…

…

…

An-1

Stay in bed

20u

240u

An

Ignore Joe’s call

-30u

100u

9

Value of consequences of Aφ

given the option-set {1,…,φ}

200u

In this situation, the traditional interpretation of act-consequentialism would require

Jill to do charity-work. This is because that action has the best consequences when

we compare all the actions as required ones.

However, we can apply the

Consequentialist Options principle, when we ask whether morality understood in

consequentialist terms should grant Jill also an option to go Paris. On this proposal,

morality should not deny Jill this additional option on consequentialist grounds if

her going to Paris (the initially suboptimal action) would have better consequences

when she is able to choose between it and the charity-work option than her doing the

optimal action (charity-work) when that action is required.

The value of the consequences of Jill choosing to go to Paris when it would

have been also permissible to do charity-work is 210u. The consequences of going

to Paris are 60u better when this action is a consequence of a choice between Paris

and the charity-work than they would have been had that action been required.

Thus, the consequences of Jill choosing to go to Paris given the option-set {charitywork, going to Paris} are better than the consequences of her doing charity-work

when she would have been required to do so. This entails that morality should, for

consequentialist reasons, grant her the additional option of going to Paris.

At this point, Jill’s permissible options are either to do charity-work or to

go to Paris. Should morality, understood in consequentialist terms, also grant her a

third option of visiting her parents? In order to answer this question, we should

again consult the Consequentialist Options principle. The table above shows that, if

Jill visits her parents when she it is permissible for her to do so, go to Paris, or do

charity-work, the value of the consequences will be 215u. We should then compare

this amount of value to the value of Jill going to Paris when she would have only the

10

slightly smaller option-set of either going to Paris or doing charity-work. The value

of the consequences of that action in those circumstances is 210u.

This means that Jill having also the third option of visiting her parents has

better consequences, whatever she ends up doing, than if she were only free to

choose between the previous two options we already granted her and she then chose

the least valuable option. This is why morality should grant her also the third option

of visiting her parents. By iterating this process, we can step by step determine

which options Jill has on consequentialist grounds.

According to the table above, morality would stop granting her more

options on consequentialist grounds when we come to Jill’s action of ignoring Joe’s

call. If Jill were able to freely choose to ignore Joe (when also having the more

valuable options), the consequences of this action would be 100u in total. If she

chose to stay in bed when not being allowed to ignore Joe (the least valuable action

of the smaller option-set), the consequences would be better, 240u. This means that

Jill would only be permitted to choose between staying in bed and all the other

actions she could do which would have better consequences when chosen from the

relevant option-set.

We should recognise that the Consequentialist Options principle itself is merely a

formal principle for determining which actions are morally permissible in the

consequentialist framework.

The previous example also illustrates how that

principle on its own cannot tell us which actions are permissible. That depends on

how much more valuable (if at all) the consequences of actions are when the agent is

able to choose those actions from different sized sets of permissible options.

11

The previous section tried to explain certain considerations which could, on

occasion, make the consequences of actions resulting from choices between many

permissible options more valuable. However, already the previous example shows

how complex issues we are dealing with at this point.

I merely selected, for

illustrative purposes, the values of the consequences of different possibilities so as to

get the right intuitive options for Jill. If this were an actual choice-situation, in order

to fill in the table correctly, we would need to know (i) whether Jill enjoys making

choices between many permissible options, (ii) what kind of representational value

her choices could have, (iii) which choices are necessary for the recognition of her

abilities for making reasonable choices, and so on. All this information would be

required for knowing which actions would be permissible given the Consequentialist

Options principle.

However, the point of introducing that principle is more structural than

practical.

According to the freedom-objection, we always have more morally

permissible options than act-consequentialism would entail.

However, if the

Consequentialist Options principle holds, then how many options we have depends

on how much better the consequences of our actions are when these actions would

belong to our option-sets. If choices between many permissible options can make

the consequences of actions a lot better, then we will have a lot of options. In

contrast, if no additional value is gained from choices between many permissible

options, then consequentialism would still not create many options.

All of this means that whatever options we intuitively think we have in a

given situation, there will be a version of consequentialism that entails that very

number of morally permissible options. There will be a way of assigning additional

value for the consequences of actions which can chosen from sets of permissible

12

options such that (i) the consequences of the agent-having that option-set (no matter

which action the agent chooses from it) are not worse than the agent doing the least

valuable action from the more limited option-sets, and (ii) giving the agent a more

extended option-set could have worse consequences.

If this right, then there cannot be an objection to consequentialism per se

that it does not provide enough options. This means that the freedom-objection

debate will then be no longer be about consequentialism, but rather about whether

the views of the value of choices. If the required view about the value of choices

between many options that has the right results does not turn out to be plausible,

then one could argue that at least the most plausible versions of consequentialism do

not provide all the options we think we have.

However, at this point, the

consequentialist could claim that she has been able to make her view compatible to

most of our intuitions about moral options.

5. Let me finish by making two observations. The first one of these concerns the

axiology which the consequentialist would need to be able to defend to get a

sufficient number of moral options. Consider the permissible actions A1 (charitywork) to An-1 (staying in bed) in the previous example. If we ignore the value of

these actions resulting from choices between many options, A1 has the best

consequences, A2 has slightly worse consequences, and so on, all the way to the

almost neutral consequences of An-1. Yet, every time Jill is granted a new option (an

action less valuable in itself), the results of Jill doing this action out of a choice

between many options would have been better than the results of her doing the

previous action in the ranking from the slightly smaller option-set.

13

This requires that, when we go down the scale of actions and towards the

larger option-sets, more value must be added to the consequences of actions as a

result of them having been chosen from the slightly larger option-set.

The

difference in value between doing A2 when required and doing it with the option-set

{1, 2} was 60u, the difference between doing A3 when required and doing it with the

option-set {1, 2, 3} was 115u, and so on.

To some extent, such pattern of increases in the value of choice is plausible.

If one has only two options, one would want to have more of them, one’s actions

would not really be representative of one’s thoughts, one’s deliberation-abilities

wouldn’t really be recognised, and so on. So, being able to choose the second option

out of an option set of two would not add that much value to the consequences of

that action. However, if one had three choices instead, maybe one would get a bit

more of the choices one wanted, the results of one’s actions would be a bit more

representative of one’s inner world, one’s abilities would be a bit more recognised,

and so on. Similar increases would presumably take place if we added a fourth

choice, a fifth choice, and so on.

However, at some point, the added value of the new options would begin to

decrease due to the diminishing marginal utility of having more permissible options

to choose from. The value added to the consequences of actions by the fact that

there were more options to choose from would at that point stop compensating for

the fact that the other consequences of these actions are always a bit less valuable. It

is rather difficult to assess whether this would happen too quickly so that the

consequentialist framework could still not create enough permissible options.

The second observation I want to make is that the previous proposal does

require revising the deontic element of act-consequentialism. However, I hope that

14

this change is motivated on purely consequentialist grounds. It is true that the basic

act-consequentialism requires, by definition, that all agents always to do whatever

action has the best consequences in the given situation. My claim is that the

consequentialist should not say this, if she thinks that whatever moral requirements

we have is determined by whichever moral requirements would have the best

consequences. If morality is understood by using this basic consequentialist idea,

then agents can only be required to choose between actions which belong to the

options-sets which are optional according to the Consequentialist Options principle.

Bibliography

Bradley, Ben (2006): “Against Satisficing Consequentialism”. Utilitas 18, pp. 97–

108.

Dworkin, Gerald (1988): The Theory and Practice of Autonomy (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press).

Kagan, Shelly (1989): The Limits of Morality (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Pettit, Philip (1984): “Satisficing Consequentialism”. Proceedings of the Aristotelian

Society, Suppl. Vol. 58, pp. 165–176.

Pettit, Philip (1996): “The Consequentialist Perspective”. In Baron, M., Pettit, P. &

Slote, M.: Three Methods of Ethics (Oxford: Blackwell), pp. 92–174.

Portmore, Douglas (2003): “Position-Relative Consequentialism, Agent-Centred

Options, and Supererogation”. Ethics 113, pp. 303–332.

Scanlon, T.M. (1998): What We Owe to Each Other (Cambridge, Ma.: Belknap

Press).

Scheffler, Samuel (1982): The Rejection of Consequentialism (Oxford: Oxford

University Press).

Slote, Michael (1982): “Satisficing Consequentialism”. Proceedings of the

Aristotelian Society, Suppl. Vol. 58, pp. 139–164.

Vallentyne, Peter (2006): “Against Maximizing Act Consequentialism”. In Dreier, J.

(ed.): Contemporary Debates in Moral Theory (Oxford: Blackwell), pp. 21–37.

15