Federalism as a Constitutional/Legal System

advertisement

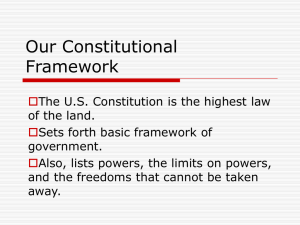

Federalism as a Constitutional/Legal System As a constitutional or legal concept, federalism refers to a system of government in which constitutional powers are divided between two levels (national and state). [Review material on federalism from previous treatment of the U.S. Constitution (i.e., 6 characteristics of constitutional federalism).] The U.S. Constitution creates (or acknowledges) two levels of government: • The national government is a government of delegated (enumerated) powers; • The states are governments of reserved powers [10th Amendment]. The Nature of the National Government’s Constitutional Powers Whatever constitutional powers the national government possesses are delegated by the Constitution. However, throughout the 200+ years of our constitutional history, there has been some question as to the extent of the powers actually delegated. As a matter of fact, the national government two types of delegated powers: • expressly delegated powers (those specifically mentioned in the Constitution) and • implied delegated powers (those that are delegated by the Elastic Clause - Article I, section 8:18). The Evolution of Constitutional Federalism in the United States There two distinct periods of development of intergovernmental relations (IGR) - that is, relations between the national and state governments - in the United States since the Constitution was ratified in 1789: • 1789 to (roughly) 1900 [this period was characterized by conflict or antagonism between the two levels] • 1900 to the present [this period has been characterized more by cooperation between the two levels, although occasionally conflicts still emerge] Federalism in the 19th Century Whereas the federalism of the 19th century was marked by constitutional/legal conflict between the two levels of government, the Supreme Court played a pivotal role in the evolution of constitutional federalism. There were two dominant interpretations of federalism during this period. • 1801 - 1835 The Marshall Court -- “National Federalism” • 1835 - 1863* The Taney Court -- “Dual Federalism” *Some historians and constitutional law scholars argue that, even though Roger Taney left the Court in 1863, his philosophy of “dual federalism” continued to dominate decisions of the Supreme Court until at least the turn of the 20th century. Still others contend that the Taney philosophy underlay the decisions of the Supreme Court until the 1930s, particularly in cases dealing with interstate commerce. Comparison of the Marshall and Taney Interpretations Interpretation of: Doctrine of Implied Powers Relationship between 2 Levels Emphasizes the Elastic Clause [Article I, section 8:18] John Marshall (1801-1835) “National Federalism” Roger Taney (1835-1863--1900) “Dual Federalism” “....there is no phrase in the instrument (the Constitution) which like the articles of confederation (sic) excludes incidental or implied powers; and which requires that everything granted shall be expressly or minutely described....” (McCulloch v Maryland, 1819] Emphasizes the Supremacy Clause [Article VI, par 2] - National supremacy “...it has been contended that if a law passed by a state....comes into conflict with a law passed by congress (sic) in pursuance of the constitution (sic), they affect.... each other as equal opposing powers. But the framers....foresaw this state of things, and provided for it, by declaring the supremacy not only of itself, but (also) of the laws made in pursuance of it.” (Gibbons v Ogden, 1824] Emphasizes the reserved powers [10th Amendment] De-emphasizes the Supremacy Clause [Article VI, par 2] - Dual sovereignties “....every power delegated to the national government must be expounded in coincidence with a perfect right in the states to all that they have not delegated; in coincidence too, with the possession of every power and right necessary for their existence and preservation....” (Abelman v Booth, 1859] “....This judicial power was justly regarded as indispensable, not merely to maintain the supremacy of the laws of the United States, but also to guard the states from any encroachments upon their reserved rights by the general government. So long as this Constitution shall endure, this tribunal must exist with it, deciding....the angry and irritating controversies between sovereignties....” [Abelman v Booth] Constitutional Interpretation Broad constructionist “we (the Supreme Court) are not restrained....from construing the words of the Constitution; defining the judicial power in their true sense. We are not bound to construe them more restrictively than they naturally import....There is nothing so extravagantly absurd....as to require the words which import this power should be restricted by a forced construction....” [Cohens v Virginia, 1821] Strict constructionist “....the Constitution speaks not only in the same words, but with the same meaning and intent with which it spoke when it came from the hands of the framers....” [Dred Scott v Sanford, 1857] Another Illustration: Missouri v Holland [1920] • Facts of the case: By a treaty of 1916 the United States and Great Britain undertook the regulation and protection of birds migrating between Canada and various parts of the United States. An Act passed by Congress in 1918 gave effect to the treaty by establishing closed seasons and other rules. The state of Missouri pursued legal remedies to prevent the game warden of the United States [Holland] from enforcing the act. • The constitutional issue: Does Congress have the constitutional power to establish hunting seasons and other rules? The state of Missouri claimed that under the 10th Amendment the authority to establish hunting rules is a power of the state, because the power is not specifically delegated to Congress. • The decision of the Supreme Court: The Supreme Court ruled that the act of Congress was constitutionally valid and enforceable by Holland. • The reasoning behind the decision: Article II, sec. 2 of the Constitution specifically delegates the treaty-making power to the president. Article VI, par. 2 declares the supremacy of the Constitution, treaties made under the authority of the United States, and acts of Congress made in pursuance of the Constitution. Additionally, Article VI, par. 2 requires that “the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.” Since the treaty is made under the constitutional authority of the United States, laws made by Congress pursuant to the treaty are the supreme law of the land. Furthermore, Article I, sec. 8:18 gives Congress the power “to make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution” the delegated powers of Congress “and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or any Department or Officer thereof.” Whereas the president is an officer of the United States government, and the Constitution delegates the treaty-making power to the president, Congress may make laws that are necessary and proper to execute the treaty of 1916. In the Supreme Court’s view, the Act of 1918 is a necessary and proper means to execute the provisions of the treaty. • Implications of the case: Although the relations between the national government and the state governments has been characterized more by cooperation during the 20th century than by legal/constitutional conflict, constitutional controversies over federalism occasionally come before the Supreme Court. Missouri v Holland is a good representation of the Court’s general position on federalism during the 20th century. Brennen’s v Meese’s Construction ….Those who framed the Constitution chose their words carefully; they debated at great length the most minute points. The language they chose meant something. It is incumbent upon the Court to [uphold] that meaning…. ….We current justices read the Constitution in the only way we can: as 20th century Americans. We look to the history of the time of framing and to the intervening history of interpretation. But the ultimate question must be, what do the words of the text mean in our time? For the genius of the Constitution rests not in any static meaning it might have had in a world that is dead and gone, but in the adaptability of its great principles to cope with current problems and current needs. ….from an address to the American Bar Association, July 9, 1985 ….from a speech at Georgetown University, October 12, 1985