Benjamin Gibson, Scott Shults, Heather Jackson, Russell Fox, & Dr. Chris Dula

advertisement

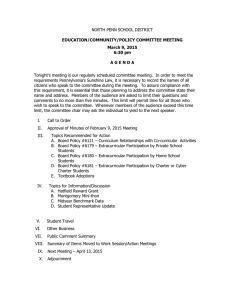

Benjamin Gibson, Scott Shults, Heather Jackson, Russell Fox, & Dr. Chris Dula East Tennessee State University It is known that factors within the classroom influence GPA , however, there is also growing interest regarding the effects of non-academic factors. • Effects of self-efficacy, SES, extracurricular activities, church attendance, home environment, and family conflict on the GPA (Bandura, 1993; Eccles & Templeton, 1999; Eccles, et al., 2003; Jordan & Nettles, 2000; Hossler, Schmit, & Vesper, 1999; Koenig & Valliant, 2009). Research suggests a positive relationship between involvement in extracurricular activities and GPA for elementary, middle school, and high school students. • extracurricular activities provide access to role models, discouraging them from delinquent activities (Eccles & Templeton, 2002; Silliker & Quirk, 1997; Mahoney & Cairns, 1997; Powell, Peet, & Peet, 2002). A Matter of Time suggested that productive use of time contributes to successful adolescent development. It outlined the amount of discretionary time adolescents have and how much of this time is spent on unstructured activities such as (i. e. “hanging out”, watching t.v., & listening to music (The Carnegie Corporation, 1992). • Structured activities would benefit adolescents because: (a) idle time is the devil’s playground; (b) learning can occur, and (c) establishes positive social supports and networks, such as role models, (Eccles & Barber, 2003) . Routine Activities Theory Other disciplines (criminology) have also studied this topic, concluding that how and where time is spent is a good predictor of deviance (Vazsonyi, et al., 2002) Routine activities theory explains such increases in deviance as cybercrime, robbery, and other violent crimes (Felson & Cohen, 1979; Furnell, 2002; Holt & Bossler, 2009; Spano & Nagy, 2005). • For instance, in a study of young adults, Osgood, et al. (1996) suggested a positive relationship between unstructured socializing and deviant behavior. Results reinforce the theory that participation in structured extracurricular activities (i.e. school clubs and sports) can reduce the likelihood of students participating in deviant behaviors. Literature also exists outlining possible adverse effects of extracurricular activities on GPA. • Employment may be viewed as an extracurricular activity, and has been found to be negatively related to study time (Ehrenberg & Sherman, 1987; Oettinger, 2005; Stinebrickner & Stinebrickner, 2003). Ambiguity surrounding this interaction merits further investigation Grych and Fincham (1990) have proposed that although optimal exposure to family discord can be beneficial by teaching children coping skills, too much exposure to family conflict can lead to maladjustment. • This in turn can lead to a myriad of problems, such as psychological disorders, delinquency, and increased likelihood for dropping out of high school. A meta-analysis by Hawkins and colleagues (2000) linked family conflict and academic failure as predictors of adolescent violence, suggesting a correlation between discord in the home and academic performance. Research conducted by Seipp (1991) linked anxiety to poor academic performance. • This suggests that family conflict may influence factors, such as anxiety which then affect academic performance. Oh (1998) found that 12th-grade students with higher levels of religiosity averaged of as much as 22 percentile points higher in GPA over less religious 12th-graders. • Some researchers hypothesize that these findings are due to the social support provided by belonging to an organized religion (Smith & Denton, 2005). However, they may also be explained by higher expectations and aspirations being associated with traditional religious values (Oh, 1998). • Although previous literature has linked church attendance and family problems such as divorce, to date, research has failed to examine the possible relationship between church attendance and overall family conflict (Hadaway, Marler, & Chaves, 1997). H1: It is hypothesized that family conflict will have a negative relationship with grades. H2: A positive relationship between participation in extracurricular activities and grades is also expected. H3: It is anticipated that students who report a higher prevalence of church attendance will have a higher GPA as well. H4: It is also hypothesized that church attendance will be negatively related to reports of family conflict. H5: Exploratory analyses will be conducted to investigate the possible relationship between family conflict and participation in extracurricular activities. Participants/Procedure Data comes from the Gear Up Tennessee Program. • $21 million, federally funded, state initiative aimed at increasing educational expectations of students and their families, enhance academic preparation, provide effective professional development, and encourage community engagement. were 499 8th and 9th grade students from rural middle schools in the Southeastern United States. Participants • 250 (50.1%) were male and 249 (49.9%) were female. • 232 (46.5%) were 8th graders and 267 (53.5%) were 9th graders. Participants were excused from class and asked to participate in a brief survey and were free to assent. Grades were attained directly from the schools’ offices. Measures A general survey was used to gather self-reported information on age, sex, living arrangements, extracurricular activities, and grade level in school (self-reported). Participation in Extracurricular Activities was assessed by asking the question: “So far this school year, which of these after-school activities have you done? (Mark all that apply)” • Respondents were then given the following answers: Sports team/cheerleading, Chorus or Band, Dancing/Gymnastics, School Clubs, Boy Scouts or Girl Scouts, and Tutoring. Family Conflict • A subscale of the Family Environment Scale (Moos & Moos, 1986), which examines specific dimensions of the family environment, such as the interpersonal relationships within a family, the importance placed on personal growth within the family, and the organization of the family structure; all of which are areas important to the positive development of a family Church Attendance was assessed with a statement that reads “I usually go to church:” • Respondents are then given the following answer set to choose from: Every week, 2-3 times a month, About once a month, A few times a year, Never. Results H1: Supported. Family Conflict was significantly negatively related to GPA • (r = -.207, p < .001) H2: Supported. Participation in Extracurricular Activities and GPA were significantly positively related • (r = .350, p < .001) H3: Supported. Church attendance was positively related to GPA • (r = .161, p < .001) H4: Supported. Church attendance and family conflict were negatively related • (r = -.274, p < .001) H5: Exploratory analyses revealed a negative relation between Family conflict and participation in Extracurricular Activities • (r = -.144, p < .001) Table 1 Family Conflict GPA Extracurricular Activities Church Attendance Family Conflict 1 -.207** -.144** -.274** GPA -.207** 1 .350** .161** Extracurricular Activities -.144** .350** 1 - Church Attendance -.274** .161** - 1 ** p < .01 The results showing a negative relationship between family conflict and grades suggest that students do not keep their home and school lives completely separated. Instead they can influence and affect one another. These results suggest participation in extracurricular activities offers students structured activities that fill their free time and can teach them lessons about work ethic that translate into their academic studies. The results showing a positive relationship between church attendance and grades suggest that the church environment provides the support that can nurture and promote good study habits. Likewise, the negative relationship between church attendance and family conflict could be explained through the teaching of certain traits such as compassion and forgiveness. Results from the exploratory analysis show a negative relationship between participation in extracurricular activities and family conflict. Perhaps extracurricular activities can increase one’s sense of teamwork, which could be related to a decrease in family conflict. Overall, results point to the importance of factors outside the classroom, from the church to the home to the extracurricular activities. The sample consisted of middle and high school students from a rural area, which may not be representative of the population. This may limit generalization of results to other geographical regions or urban zones. All measures were self-report instruments. This type of instrument is especially vulnerable to response biases, such as self-report bias. Students may be motivated to present themselves in a more favorable manner. The issue of generalizability can be addressed through the unique properties of the GEAR UP project. Examination of the possible adverse effects of certain extracurricular activities on academic achievement should be conducted. Investigation into the relationship between participation in extracurricular activities and family conflict are needed to support or supplant the findings of this study. Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational Psychologist, 28, 117-148. Carnegie Corporation of New York (1992). A matter of time: Risk and opportunity in the nonschool hours. New York: Author. Crocker, J., & Park, L. E. (2004). The costly pursuit of self-esteem. Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), 392-414. Downey, D. B. (1995). When Bigger Is Not Better: Parental Resources, and Children’s Educational Performance. American Sociological Association, 60(5), 746-761. Eccles, J. S., & Barber, B. L. (1999). Student Council, Volunteering, Basketball, or Marching Band: What kind of extracurricular involvement matters? Journal of Adolescent Research, 14(1), 10-43. Eccles, J. S., & Templeton, J. (2002). Extracurricular and other after-school activities for youth. Review of Research in Education, 26, 113-180. Eccles, J. S., Barber, B. L., Stone, M., & Hunt, J. (2003). Extracurricular Activities and Adolescent Development. Journal of Social Issues, 59(4), 865-889. Ehrenberg & Sherman, 1987? Felson, M., & Cohen, L. E. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review, 44, 588-608. Freeman, J. (2003). Gender differences in gifted achievement in Britain and the U.S. Gifted Child Quarterly, 47(3), 202-211. Furnell., S. (2002). Cybercrime: Vandalizing the Information Society. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley. Hadaway, C. K., Marler, P. L., & Chaves, M. (1993 or 1997?). What the pools don’t show: A closer look at U.S. church attendance. American Sociological Review, 58(6), 741752. Hadaway, C., & Roof, W. (1988). Apostasy in American Churches: Evidence from national survey data. In D. Bromley (Ed.), Falling From Faith, 29-46. San Francisco, CA: Sage. Holt, T. J., & Bossler, A. M. (2009). Exmaining the Applicability of Lifestyle-Routine Activities Theory for Cybercrime Victimization. Deviant Behavior, 30, 1-25. Hossler, D., Schmit, J. & Vesper, N. (1999). Going to college: How social, economic, and educational factors influence the decisions students make. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. Jordan, W. J., & Nettles, S. M. (2000). How students invest their time outside of school: Effects on school-related outcomes. Koenig, L. B., & Valliant, G. E. (2009). A prospective study of Church Attendance and Health Over A Lifespan. Journal of Health Psychology, 28(1), 117-124. Loury, L. D. (2004). Does church attendance really increase schooling? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 43(1), 119-127. Lui, L. C., & Flay, B. R. (2009). Evaluating mediation in longitudinal multivariate data: Mediation effects for the Aban Aya Youth Project drug prevention program. Prevention Science, 10(3), 197-207. Mahoney, J. L., & Cairns, R. B. (1997). Do extracurricular activities protect against early school dropout? Developmental Psychology, 32, 241-253. Mesch, G. S. (2009). Parental mediation, online activities, and cyberbullying. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 12(4), 387-393. Milevsky, A., & Levitt, M. J. (2004). Intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity in preadolescence and adolescence: Effect on psychosocial adjustment. Mental Health, Religion, and Culture, 7(4), 307-321. Osgood, D. W., Wilson, J. K., Bachman, J. G., O’Malley, P. M., & Johnston, L. D. (1996). Routine activities and individual deviant behavior. American Sociological Review, 61, 635-655. Oettinger, 2005? (Oettinger, 1999 available) Oh, D. M. (1998). Evidence on the correlation between religiosity and social/psychological behavior and the resulting impact on student performance. Dissertation Abstracts International, 59(11). Powell, D. R., Peet, S. H., & Peet, C. E. (2002). Low-income children’s academic achievement and participation in out-of-school activities in 1st grade. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 16(2), 202-211. Silliker, S. A., & Quirk, J. T. (1997). The effect of extracurricular activity participation on the academic performance of male and female high school students. School Counselor, 44(4), 288-293. Smith, C., & Denton, M. L. (2005). Soul searching: The religious and spiritual lives of American teenagers. New York: Oxford University Press. Spano, R., & Nagy, S. (2005). Social Guardianship and Social Isolation: An application and Extension of Lifestyle/Routine Activities Theory to Rural Adolescents. Rural Sociology, 70(3), 414-437. Stinebrickner & Stinebrickner, 2003? Vazsonyi, A. T., Pickering, L. E., Belliston, L. M., Hessing, D., & Junger, M. (2002). Routine activities and deviant behaviors: American, Dutch, Hungarian, and Swiss Youth. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 18(4), 397-421.

![Educational Setting – Offer of FAPE [IEP7B] English](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006809815_1-704b6bcef8e9a29f73a2206ea1b6ed19-300x300.png)