“Not in my back yard!” Irrationality and corporate change programmes Richard Martin

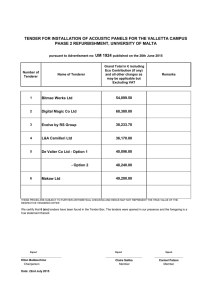

advertisement

“Not in my back yard!” Irrationality and corporate change programmes Richard Martin 10 May 2005 MartinR@Dumar.co.uk www.dumar.co.uk © Du-Mar Ltd The cost of failed change • In 1995 American companies and government wasted $81 billion on failed programmes of technology change; • This represented 31% of all projects; • In large companies only 9% of projects delivered on time and budget; • Of the projects that overran an additional $59billion was spent to complete them; • These completed projects possessed an average of 42% of their originally intended scope; • These completed projects were on average 189% over their original budget estimates and 222% over their original timescale. (Source : The Standish Group. 1997 Paper Entitled ‘Chaos’) © Du-Mar Ltd The “Change fails because…” slide The same research highlighted the following reasons for failure: • Case inadequately established, articulated, insufficiently agreed etc; • Inadequate requirements gathering & inadequate attention to requirements; • Inappropriate technology for intended function / strategic direction or poorly implemented; • Poor scope control; • Ineffective programme planning & management; • Inadequately resourced (skills, numbers etc); • Inadequate involvement of the customer; • Quality benchmarks not defined and not controlled; • Too much interference by current practice in design of intended world; • Decision-making forgets programme principles. (Source : The Standish Group. 1997 Paper Entitled ‘Chaos’) © Du-Mar Ltd AC’s change imperative (Had it been a public company) by 1997, Andersen Consulting would have been 292 on the Fortune 500. $6 Billion by turnover; 50,000 staff. No shareholders. All growth had been organic. (David Whitford, Fortune Magazine, Nov 10 1997.) From 1995 AC recognised it had to re-organise internally to: • • • • consolidate and ‘de-risk’ the firm’s approach to market (demand side); minimise problems of the internal organisation (supply-side); simplify the internal organisation, remove skills overlap and waste; leverage the skills learned from each project; Make each engagement more profitable as the needs of the larger consulting organisation eroded margins. Much of this was in response to its own growth and experiences, part in response to the rest of the consulting market (i.e. positioning – looking over the garden fence) © Du-Mar Ltd “Breakthrough” This change was to be achieved by: • • • • • • Devolving management from Chicago and regrouping into geographical regions; Regionally re-engineering the client sales processes and client risk management; Clarify and enhance engagement financial management; Re-engineering its demand and resource management using ‘collaborative’ software - linked with the sales process; Re-focusing the practice around core skills (supply) and focussing partners around industry portfolios (demand); Re-engineering its career & appraisal structure & method to meet the new practice framework, but still generate partners. In 1995 Project “Breakthrough” was born. The aims were noble and the potential solution, elegant. © Du-Mar Ltd Drip-through? I joined the programme in early 1996 as it was being re-planned; By early 1996, the programme was being called something other than “Breakthrough” and bore characteristics Standish say contribute to floundering change projects; It was a project in need of external consultants! It is testament to the company that this was recognised, fixed and the project delivered; But…we were the consultants…what had happened? © Du-Mar Ltd Break-wind? Eliminate the key aspects of the project disciplines that Standish tells us work - or whose absence cause failure: Client Breakthrough • Resource skills & numbers • • • • Best-in-industry strategy applied Best processes at our fingertips Cutting-edge technologies used in the correct way Best-in-industry programme management So what was the difference on breakthrough? Asked a different way – on client engagements on which we were very successful, what dynamics of consultancy perhaps worked for us even without our knowledge? I took the next step. © Du-Mar Ltd Not in My Back Yard and Corporate size Oliver Williamson’s Corporate Paradox. “Vertically integrated organisations cannot keep growing ever upward. Costs rise to a level where mechanisms to allow further growth are more costly than not growing; the goals of groups or subgroups in an organisation start to outweigh its common aims; the proliferation of internal controls and specialists to avoid this situation become more expensive; sunk costs encourage the persistence of existing ways of doing things even if they should not now be done that way; communication becomes increasingly distorted; leaders become increasingly distant from those they lead and cooperation between those at lower levels becomes perfunctory rather than wholehearted. Coordination and common purpose lapse.” Oliver E. Williamson ‘Economic Organisation’ Wheatsheaf books, 1986 quoted in Derek S. Pugh & David J. Hickson ‘Writers on Organisations’ Fifth Edition Penguin Books 1996 p28. © Du-Mar Ltd Corporate size and NIMBY "Ice berg warning in his hand and he's ordering more speed. Twenty-six years of experience working against him. He figures anything big enough to sink the ship they're going to see in time to turn. The ship is too big with too small a rudder. Doesn't corner worth a damn. Everything that he knows is wrong.“ (James Cameron – Titanic) Put in the context of Oliver Williamson’s corporate paradox: • The ‘normality’ of our existing context masks how bad a starting position we have; not how good; • We mis-perceive cues about the change and overestimate our ability to cope with them; Psychological studies of rationality label this ‘Overconfidence’. Also consider with large groups: • The natural effect of too many people on too little turf is to identify; collude and then divide, not unite. The net effect is ‘Avoidance’. (Not apathy. ‘Avoidance’ is active) © Du-Mar Ltd Overconfidence Decisions made in the face of complexity are haplessly (we can’t help it) Overconfident. • Getting the baseline wrong – A false belief that the prevailing organisation is a rationally constructed entity and that your starting point is “we’re ready for change” as opposed to “we need to start again”; • Context - Has the sponsor mis-construed the current sense of urgency? • Risk - Has the sponsor got the odds wrong? What is the level of threat perceived and level of risk being entered into if you change – and in the way you intend changing? • Experience - have they made the automatic assumption that experience confers predictive ability rather than look for what is new in the present situation? • Ignoring / Distorting evidence - Have they looked for evidence against their position before committing to it, or just all the evidence that supports it? • Consistency - Is there some previous decision or commitment or posture (e.g. with the city) with which they are maintaining consistency? © Du-Mar Ltd Overconfidence Available information Actual fact Our belief Fail to cut losses We’re committed anyway Distort evidence Ignore new evidence There’s the proof We know about this Coincidence - make the association Time (or subsequent events) “The human understanding is of its own nature prone to suppose the existence of more order and regularity in the world than it finds. And though there may be things in nature which are singular and unmatched, yet it devises for them parallels and conjugates and relatives which do not exist” – Francis Bacon. © Du-Mar Ltd Avoidance The behaviours of groups of people are haplessly (we can’t help it) Avoidant: • Conformity – A group will do more to maintain its social cohesion than do what is necessarily right; • Consistency – A group will adhere to its norms and values including past decisions committed to as a group rather than do what is necessarily right; • The Bystander effect – Individuals in a group tend to de-tune individual responsibility and commitment to the apparent level consistent with maintaining group conformity – or to the group’s leader if there is one; • Obedience – People tend to be unquestioningly obedient in the presence of a credible authority figure; • Motivation – Productivity increases where individuals believe they have had input / opted to do a task out of choice (they “buy into”) . Productivity decreases in tasks in which individuals have had no input / in which they have no choice (they don’t “buy into”). Dispassionate change is therefore not possible – without the risk of dissent and sabotage; • Too many people on too little turf generates irrational competitiveness – (doing colleagues down, lack of assistance etc.) “What company are you working for?” © Du-Mar Ltd The net effect of overconfidence and avoidance The net effect of these heuristics is that far from generating certainty, direction and a groundswell in an intended programme of change, the sponsors unwittingly generate exactly the conditions for its failure – at the point they hand-over responsibility for the work to the Change Programme itself, their own job ‘done’. The autonomic nature of these behaviours implies that it is not a remote possibility they have influenced a change programme but a starting assumption; Standish figures for 1995 identified 31% of large IT-driven change projects failed totally; only 9% delivered on time; remaining delivering projects (60%) possessed on average only 42% of their intended scope. The sponsors’ probable receptiveness to this possibility? “Not in my back yard!” © Du-Mar Ltd Why are consultants successful? • They rarely back losing – or risky - horses. When they do, we hear about it; • “Objectivity” (Actually - Competitiveness; no Commitment to past decisions). • They don’t accept the existing organisation as efficient; • They are already an “out group”. What does this do? Sparks cohesiveness amongst the client and ‘we can do too’ (focus on similarities over the garden wall). • Coalition - They bring their own well-knit hierarchy into whatever communications / political chaos may prevail. They have also defined that chaos within the client – even if the client has not. Implicitly or explicitly start a process to identify and remove (human) obstacles to the vision; • Sense of urgency. • Create the perception that the client cannot make it on its own – are we in trouble? • Don’t want to waste a half life of an idea in its implementation; • Surrogate for hard board decisions; • They are visibly expensive. Who dares to waste their time? And what consultant dares to be seen wasting it? • And they are very good at what Standish recommends! © Du-Mar Ltd