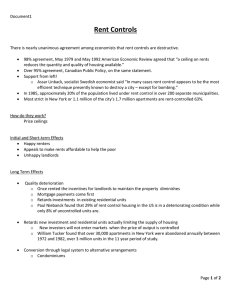

1 Final Version, Nov. 29 MASTER COPY for future changes

advertisement