Landscape Natural History ENVS-173

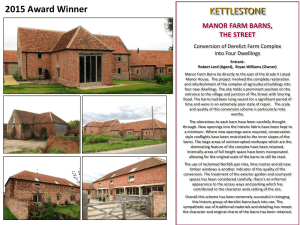

advertisement

Landscape Natural History ENVS-173 Fall-2016 --- Mondays 1:10-4:45pm Landscape, lakescape, seascape, skyscape, earthscape, …. what history was and is now unfolding in the natural tapestry that we now call the Champlain Basin and Chittenden County? How can the study of this place build tools that we can carry to any part of this globe, or other objects of the cosmos should we be so fortunate in our lifetime? From Aristotle's insights on plant lifeforms to the myriad of natural scientists that travel daily to the smallest and broadest features of Earth, we will draw upon the fundamental questions of natural history that evolved from Francis Bacon and others of the dawn of modern science – who created with the explorations of Cook and Darwin the paradigms of the great natural historians of a century ago – and reveal simple pictures of local events in the interwoven scapes of many scales viewed so wonderfully from College Hill. Time, space, dimensions – along with entities and energy – bring forth patterns built by processes constrained by simple principles in complex interactions. We will study these not as Watson, but as Mr. Holmes (Sherlock, that is) always asking deductively to what each observable is a clue. Our axioms are the principles and facts hard won through centuries of observation combined with inductive and experimental research. Yet this Western approach is but one investigative and epistemological tool, indigenous knowledge and the wisdom of Coyote bring other insight and realities. Our tasks will be to expand simple knowledge of things and events in the natural world around us, to attain new perspectives and percepts along with the concepts underlying fundamental principles, to practice the practical skills of seeing and discovering in the world immediately about us, to sharpen our deductive sleuthing techniques, and to learn to synthesize simple knowledge into great stories. Let's head to the fields, lakes, ledges and hedges!! …….. Ian Course Format All of our course time will be in the out-of-doors. It is essential that you dress appropriately so that you can comfortably do the work of each field trip. Since a goal of the course is that you continually learn more about weather and weather resources, you should not encounter weather surprises as you dress for each class day. You will also be spending some other times in the field in small groups, so there too be well prepared for conditions. Although none of our field trips are long nor accompanied by great exertion, do bring all the fluids and food you need. Also, bring the following: --Camera or cellphone for digital pictures (necessary for every class and group project field work) --Notebook; for rainy days or wet sites you might want a small waterproof field notebook --Books: the tree, communities, and weather field guides For your computer … --Load Google Earth. Level of Course and Prerequisites This course assumes that you have had at least one introductory natural science course and/or ENVS-1 or NR-1 or equivalent experience, and are at least a sophomore. Thus some understanding of natural landscapes is presumed. All assignments require at least sophomore level work. Books Wetland, Woodland, Wildland (Thompson and Sorenson)… Reading the Forested Landscape (Wessels)… The Weather Identification Handbook (Dunlop)… Absolutely must have! Mammal Tracks & Sign (Elbroch) Peterson's Guide to Eastern Trees (Petrides)… or equivalent Required Required Required Recommended Recommended Some Significant Resources The Sibley Guide to Birds (Sibley) Amphibians and Reptiles of New England (DeGraaf and Rudis) Tracking and the Art of Seeing (Rezendes) Scats and Tracks of the Northeast (Halfpenny and Telander) New England Wildlife – 2 volumes (DeGraaf) The Vermont Weather Book (Ludlum) The New England Weather Book (Ludlum) The USA Today Weather Book (Williams) North Woods (Marchand) Life in the Cold (Marchand) Weeds in Winter (Brown) The Trees in My Forest (Heinrich) Silvics of North America – 2 volumes (USFS) The Nature of Vermont (Johnson) Bogs of the Northeast (Johnson) Chittenden County Soil Survey Roadside Geology of Vermont and New Hampshire (Van Diver) Centennial Geologic Map of Vermont (Doll et al.) Surficial Geologic Map of Vermont (Doll et al.) Field Guide to New England Barns and Farm Buildings (Visser) Exploring Stone Walls (Thorson) 200 Years of Soot and Sweat (Rolando) Readings The required books are resources for you to draw upon. You are expected to use them thoughout the course to enhance your observational skills, and to enrich your assignments. Here is a schedule for using and reading the books, all of which you should leaf through carefully to get the gist of them and how they are laid out. The best way to learn from our books is to use them, much as you would any reference book. The second best way is to browse them, stopping to read topics that catch your eye. The third way is work your way through those parts which are essay-like. By the second class day: Skim all books; get familiar with organization, formatting of information, and how to use By the third class day: Wetland, Woodland, Wildland -- pages 260-262, 203-205, 344-346, 372-374 Weather Identification Handbook – be able to begin using Mammal Tracks – be able to begin using Guide to the Eastern Trees – be able to begin using 2 By the fourth class day: Wetland, Woodland, Wildland -- pages 7-55; also, be able to begin using on your own Reading the Forested Landscape -- pages 167-169; other sections that intrigue you By the fifth class day: be really familiar with the layout of all the books be able to comfortably use all the books as reference books you should have read all of Reading the Forested Landscape Schedule Monday Location Topics* 1:10-4:55 pm Aug 29th Centennial Woods Trees, steams, biogeomorphology Sept 5th ----- no class ----Sept 12th Shelburne Bay Park Landscape profiles Sept 19 st Delta Park – Winooski River mouth Dynamic landscape change Sept 26th Shelburne LaPlatte River Park Landscapes shaped by water and gravity Oct 3th Lone Rock Point Community classifiction & documentation Oct 10th ----- no class ----Oct 17th * Group Sites * Oct 24th Bolton Notch Cliffs Hypotheses and numerical descriptions Oct31st * Group Sites * Nov 7th Colchester Caves Caves as window to ancient & recent history Nov 14th * Group Sites * Nov 21st ----- no class ----th Nov 28 Geprag Park Where is the water? Where does it go? Dec 5th * Group Sites * Dec 12 TBD TBD Group-site presentation Dec 13 TBD TBD Group-site presentation Dec 14 TBD TBD Group-site presentation Dec 15 TBD TBD Group-site presentation Dec 16 TBD TBD Group-site presentation * At all sites we will be involved in: seeing, deducing, using unifying themes, analysis frameworks, tracking, birds, human evidence, hydrology, weather, geomorphology, pattern, process, and more. Assignment Schedule Assignment Number of persons Darkness natural history 1 Rain event 1 Weather watching 1 “My specialty” 1 Site tour and oral presentation 3-4 Site report 3-4 Attentiveness and participation 1 * double size if done by a group of two Percent of grade 12.5% 12.5% 12.5% 12.5% 10% 30% 10% Draft due if feedback desired Nov 2nd Nov 2nd Nov 30th Nov 30th --Portions anytime --- Final copy due Mon. Nov 30th Mon. Nov 30th Fri. noon Dec 5th Mon. noon Dec 8th --Wed. noon Dec 16th --- Assignments Each assignment provides hands-on experience while addressing our skill-building goals. An integral part of the course learning goals, they are done individually and in a semester-long group. 3 Format: Assignments can be done as hardcopies, e-mail attachments, PDFs, website, etc. If other than hardcopy, VERIFY BEFORE THANKSGIVING that it will come to me and I can open it !!!--This is crucial--!!! Format each assignment in a way you find attractive and that is easy for a reader to use. Text can be single spaced (double space between paragraphs). Single spacing is preferred. Submitted material can be in any font size. Text style: Use in-text citations; APA style is strongly recommended. Be sure all sources are clearly and correctly cited. If large blocks of material come from published sources, cite frequently and correctly. Illustrations: Photographs and/or hand sketches made on site or during syntheses are encouraged. Don’t fret about photographic or artistic skills – get the concepts right. Diagrams and other illustrations are to be neatly done. All illustrations (except in field notebooks), unless clearly decorative, should have: numbers (Figure 1, Graph 1, etc.) a title an informative caption, and a cited source if appropriate More, rather than less, personally prepared illustrations are recommended. Submissions: Drafts submitted as e-mail attachments will get the quickest feedback. Suites of photos can be submitted by any means ... but you’ve got to try it out with me before Thanksgiving!!!!! . Hand-written fieldnotes, hand-drawn illustrations, art work, and over-sized maps should be submitted as originals – there is no need to scan them into the final copy of an assignment. The final report for group sites is to be bound attractively (do not use a 3-ring, loose-leaf binder). The final report for group sites may have oversized materials; reference these clearly in the main text – submit them in a clearly marked protective folder, folio, map tube, or other suitable device. Word counts: Word counts are provided only to indicate approximate amount of effort and detail expected. This syllabus is done mostly in 10 point font, and averages about 470 words per page. This page has 493 words. Writing style, grammar, and punctuation should be consistent throughout. Use a writing guide such as The Writer's Brief Handbook by Rosa and Eschholtz as necessary. I strongly suggest using the APA in-text citation style. Be sure to learn how to cite Internet sources before you start gathering lots of information from the Internet. Be sure to properly cite maps, photos, and other non-text materials used. Personal effort The average student for an average grade is expected to spend 135 hours of effort for a 3.0 credit course. Counting travel time we will spend 60 hours total for class-time field trips and group work. That leaves 75 hours for your personal effort. This can be divided into some 35 hours on the group site project (done at times other than class time), and 40 hours on the readings and the other assignments. This is a guideline only; you may function best differently. 4 Grading The quality of your work will be assessed with these grades: A B C D F Outstanding; exceptional, with "something special" Well done; correct and complete Average; mostly correct and complete, not dominated by errors or omissions Poor; barely acceptable, errors or omissions prominent throughout Failure; fundamental content incorrect or absent, errors or omissions dominant throughout Grades can be based on at least three criteria: (a) skill and knowledge at a given point in time, (b) improvement in skill and knowledge over a period of time, (c) effort put forth in improving skill and knowledge. In this course the primary emphasis in grading will be placed on the quality of your work submitted for a grade, i.e. demonstrated skill (including your skill at presenting materials) and knowledge. Secondary emphasis will be placed on effort and progress. Errors in grammar, spelling, punctuation, format, style, etc. can lead to a grade reduction for any assignment. Consistency in style is expected. Each unexcused absence could drop your course grade by ½ a grade step (e.g. two absences would drop a B- to a C+). All assignments except the final report, if handed in on time, may be redone based upon overall comments by me. Upon a second grading, the new grade will replace the old. Material received after the due date may not be included in your course grade. At the conclusion of your major site report and field presentation, I may ask each individual to submit anonymously a grade for themself and each other individual in the group based upon the degree and quality of the contribution of each individual. I will independently create overall group grades for both the report and the presentation, as well as my estimate of personal grades. Then I will use all the personal grades to determine a final personal grade to which will be combined the group grade. --- Detailed Descriptions of Assignments --Note: Consult the table of assignments for the percentage of worth for each assignment for guidance on the amount of effort to give each task. Note: Read each assignment carefully before and as you do each one. Don’t miss any of the fine points. 1. Darkness natural history Where students have trouble with this assignment --- 1. Not rereading the assignment carefully just before heading out to their location to do it. 2. Doing it near a city or town. 3. Doing it on a moon-lit night. 4. Waiting weeks and weeks before writing it up. [a] Spend at least two complete hours during the full darkness of night in a field, forest, or wetland. The farther you are from city and other lights the better. Away from cities nights are darkest when cloudy. Near cities nights are darkest when clear. Bright moonlight diminishes the effectiveness of this activity; no moon, or subdued moon is best. 5 Full darkness of night occurs about 25 to 35 minutes after the end of Civil Twilight, which ends about 25-35 minutes after sunset. The darkest nights occur during the two weeks following one week after a full moon. You can access sunset and twilight times via following link. The first is for particular days and the second for a whole year. http://www.timeanddate.com/sun/usa/montpelier [a] Spend part of the time by quietly remaining in one spot, and part of the time moving quietly though the site. Do not use lights during your observation time and avoid looking at any white lights. Allow yourself 20 minutes in the absence of lights to gain your full night vision. Locations within greater Burlington, such as Centennial Woods and East Woods, do not serve well for this assignment due to the amount of city noise and lights. Likewise, choosing a night with a high, bright moon defeats some of the purpose of the assignment. It is OK to have a friend along for companionship, but do have them follow the same procedures for the assignment as you. [b] Look, listen, smell, and feel …. remembering and recording what you observe. Pay particular attention to what is observable in the dark that is overlooked during the day, as well as those things that happen or appear in the night. Be also aware of how certain things appear differently at night. Occasionally spend a bit of time identifying, using your nighttime senses (including touch by hand and foot, walking, smell, hearing, and even taste): tree species, rock types, birds, animals, insects, ecosystems, weather phenomena, hydrologic phenomena, weather, etc. Take notes from time to time, but do not use lights when writing. You can use a “key word” technique that I will explain. [c] Write a 2200-3200 word report and essay with two sections [please subtitle each section]. Section #1 records what you discovered and at your site. In this section also comment on what you observed that would likely not be observed during the day. Section #2 analyzes what can be better observed in the dark than when there is light. Your report should be filled with detailed examples and observations from the two hours that you spent. It doesn’t work to casually wander in the woods or fields, without much attention to the goals of the assignment, nor to do the report by memory several weeks later. The key words are the verbs "records" and "analyzes". The first section is a description of your discoveries. The discoveries could have to do with the amount of light there was, the shape of trees, what your feet told you as you felt your way along, the scary sounds you heard, the slimy place you put one hand while the other hand grabbed onto a pricker bush, how much better (or not) you could see after being in the dark for a while, how time went by both fast and slowly at the same time, how your companion kept wanting to check his email to the point that you took the cell phone away ...... The second section talks about those things that can be better observed in the dark from the standpoints of why the dark was a better situation than the day, how your difference senses seem to work during the dark/twilight/dark, how you might use the dark to learn more about a place, its natural history, its processes, etc., than you can in the daylight, what you would like to try doing at night and places where you might go, what nighttime skills you would like to build and practice, what experiences you really don't want to have at night, ..... Write your report and essay to include useful observations, facts, and perspectives that could be the basis for developing a darkness field trip guide at some later time for a local nature center that serves children, adults and elders. You don't have to create a guide in any way; there is no reason to even mention a guide. Write about your personal field trip. But do think of what other persons of all ages might learn from a similar field trip as you write -don't just write in the isolation of your own personal experience. By including the perspective of other persons (with all their variety of ways of seeing and experiencing) in your mind as you write, you will have a richer response to your own observations and reflections. 6 2. Rain event Where students have trouble with this assignment --- 1. Not rereading the assignment carefully just before heading out to their location to do it. 2. Not following the instructions; especially not getting to the smallest details you can. 3. Not doing items [c] and [e]. 4. Waiting weeks and weeks before writing it up. [a] During a period of relatively steady light, moderate or heavy rain (ideally heavy, but take what you can get) spend a full 2 hours observing everything that you can about the rain, the rain water, and the effects of the rain on some small area (a few tens to a few hundreds of square feet). The object of this exercise is to see rain in considerably more detail than you ever have. You cannot do this exercise by looking out windows or standing on a porch … you need to be in the rain as it is happening. You also need to move around, get right down on the ground, maybe climb a tree, look up/down/underneath/into the light/away from the light/etc., etc. Make many sketches and take lots of notes (I know, it will be raining … but by then we will have talked about how to write and sketch in the rain). Photographs are encouraged as well. [b] Be particularly interested in the rain and droplets, how they change with time, where droplets land, what gets wet, how different thing wet, what the water does, where it goes, what it carries, what it erodes, where it disappears, what it leaves as clues for the next day, week, month, and year, etc. Spend time seeing the smallest details you can … remember those days as a 5 year old you spent flat in a puddle watching bubbles form with every drop and then float about as bumper cars for bugs! Document how the rain drops dissipate and reassemble with others to pond, flow, disappear or evaporate … thus moving from the smallest minute phenomena you can observe to a scale much larger than you can document. In addition to the water itself, observe and document also what it is doing through its ability to dissolve, carry, push, erode, warm, cool, change the look of, make things slippery or easier to grasp, quench thirst, cause things to droop and sag, help plant perk up, etc., etc. Here too look very closely, and at a distance – change the scale from your everyday habits. Regarding “erosion,” in this exercise don’t spend much time with the result of erosion, but see erosion actually happening at the smallest scale you can. Watch for things to be dislodged; see them move. [c] You should also follow the rain that hits your spot to see where it goes, and speculate upon pathways that it might travel from your location over the next weeks, months, decades, and centuries. [d] Submit your observational field notes and sketches along with a documentary essay highlighting your observations. The essay will likely be around 2200-3200 words. [e] Add an additional, separate page or two which contains and discusses one thoughtful wondering or speculation that could be answered if you had the right equipment or could design a testable hypothesis. Suggest how you would go about getting the answer. 3. Weather Watching Assignment Where students have trouble with this assignment --- 1. NOT REALIZING THERE ARE 16 DIFFERENT DATA PAGES (8 per Excel file) !!!!! 2. Misunderstanding the assignment!! – How to do it, and why we are doing it. 3. Not starting right away. 4. Not making sure you know how to use the data pages … and that you are using ALL of them. 4. Not making sure I can view your photographs by whatever technique you are providing them, nor ensuring they are easy to view. 7 [a] The object of this assignment is to see a large variety of different kinds of weather and atmospheric phenomena, including optical phenomena such as rainbows and sundogs. Work to see not only common features of the sky, but their more subtle aspects (such as secondary rainbows and wind shear curls on cumulus clouds). As you see different skies, you acuity will grow building to our goal of actually observing the natural world … knowing that seeing will lead through curiosity to understanding, and then through interest lead to applications of that knowledge. [b] The two spreadsheets have 8 data pages (worksheets) per each spreadsheet. You are only required to use and fill in these seven pages. You can ignore the other pages. Low Clouds Medium Clouds High Clouds Neat Clouds Fog Types Optical Phenomena (part 1) Optical Phenomena (part 2) – Arcs & Points [c] Look for and take pictures of different sky phenomena. A number will focus on a large portion of the sky and the kind(s) of clouds present. Others will focus on different kinds of small features such as cauliflower-shaped parts of thunderheads, a whisp of fog above a manure pile by a barn, etc. If something in the sky looks interesting or different --- take a picture! Multiple-photo panoramas capturing a larger portion of the sky are often very helpful. Your photographs should be a collection of diverse cloud types, optical phenomena, etc. Expect to include 80 or more photos. [d] You will need to actually study The Weather Identification Handbook regularly as you approach and do this assignment. Not only do you have to look for things in the sky, you need to teach your eyes and mind what kinds of things to look for. [e] Don’t worry if you can’t name something. If you ask, I will assist you with this. [f] It is OK to include observations we make in class; but also plan to make many observations away from class. Use only photographs taken and observations made during the duration of the course. 4. “My Specialty” – an intensive record Where students have trouble with this assignment --- 1. Waiting till October before you begin. 2. Not being creative in locating examples. 3. Taking way too few photographs. 4. Spending too much time trying to figure out names of things in your photographs. Some students make this assignment much harder than it is intended to be --- and then only end up with a few observations (which are not an “intensive record”). Work with me closely until you are well underway! [a] Select a personal specialty – make it a topic you have some interest or passion it. It can be something you know a lot about, or something you have never explored before (indicate your initial level of knowledge at the beginning of your final document). Throughout the semester, at incidental moments and at dedicated times, notice and look for real examples, etc. You should have your topic chosen by mid-September; earlier if you are able. [b] The primary goal is for you to see your chosen things vastly better than you did before the course … better able to find them, better able to see their diversity, and in a few cases to be better able to name them. For most specialties chosen, naming the things observed is not important (for example, you don’t need to know the name of mushrooms you find and photograph … just keep finding more different kinds). 8 [c] Compile at large collection of photographs (or other documentation such as audio recordings, sketches, etc.) documenting your discoveries during everyday wanderings and dedicated searches. Use only observations made during the duration of the course. Check with me to know what “long” means for your topic. For many topics, 50 different observations is a good, minimum target. Many past topics have yielded well over 100 observations. Record the date and location for each observation. [d] Add a 1000-1500 word overview of your experience, sightings, and discoveries. This is a very minor part of the assignment, counting only 10-15% of the assignment’s grade. [e] This exercise should be built around a topic that was one of your reasons for taking the course, or a topic in which you have had curiosity for some time. It only works if you put in time on it. It does not work if you primarily use our class field trips for creating your list (but you can definitely add to your list during our class trips). 9 5. Landscape Natural History Site Assessment and Report ~~Goals~~ (1) to ascertain the fundamental landscape character of your site, its elements, patterns and process through time and space – particular interest being placed on topography, geology and geomorphology, hydrology, biotic communities, ecological relationships, human influence, and landscape history; (2) to place your site in the context of nearby landscapes, Chittenden County, the Champlain Basin, the Northeast and globally; and (3) to portray this knowledge in an interesting and informative document useful to nearby landowners, interested visitors, local land use planners, and UVM and local high school students who might choose to use the site for further study. The final report can be done by hand or computer, and can appear on paper or as a website. (4) to maintain this mantra throughout: Discover and document --- document to discover! Where students have trouble with this assignment. 1. Not reading these instructions over and over and over again and again and again throughout the entire project. 2. Being way too casual about digging into details. (See more at very end of this assignment description.) ~~Methods~~ [a] In this semester-long, group assignment you will have the opportunity to weave together the various topics we and our texts have covered into an informative interpretation of a specific landscape. Each team of three or four individuals will be responsible for investigating and analyzing a specific landscape, incorporating its findings in a bound, comprehensive written, illustrated document and an on-site oral presentation. This is the major project of the course, and the final materials will be quite extensive. The emphasis of the work is on what you find on-site. It can and will be supported by existing resources, but only the course textbooks or items you have from other courses, but the vast majority of the information should come from the site itself! This is NOT a library or on-line based activity. For most groups and individuals, the “pin-hole camera” method of investigation will be the most fruitful and rewarding technique (see below for definition). [b] Each team member is expected to spend many hours on-site (see Personal Effort section above), plus additional hours preparing illustrations, and compiling a written document. The sites provide the opportunity to study, analyze, document and interpret: [i] ephemeral features; [ii] features whose character and origins span from decades to hundreds of millions of years; [iii] the touch of humans. 10 [c] Site – Your sites can be of any shape, and should be on the order of 3-10 acres or so in size. All sites are to be in Chittenden County. They can be chosen by you or from the attached list. Our class field trip sites make good group sites. I will help you select a site if need be. By the end of your second site visit chose the specific boundaries for your site. Be able to state them with adequate precision to draw them on a map or Google Earth image. [d] Microsite – About a quarter to a third of your time is to focus on a small portion of your site, an area of particular interest or intrigue. This area can be of any shape and will likely be no larger than 100-250 feet across; it should be no smaller than about 30 feet on a side. Be sure to place this microsite in the context of your entire site. [e] When doing your work draw upon: (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) our field trips, texts, handouts, previous assignments, and the course learning objectives listed in the syllabus; previous courses you have had; your personal experiences; your imagination; discoveries you make at your site; and especially your willingness to speculate and create plausible stories. [f] Some aspect of your work should have a quantitative approach. Examples would be things such as determining the angle of slopes for parts of your site (cliffs, terraces, rock slides, etc.), measuring the diameters of trees in different communities, calculating volumes of stream flow at different stream heights, aging pine trees, estimating the proportion of your site suitable for growth of a certain tree, identifying particular individual animals by the size of their tracks and stride, figuring out how many rocks are in a certain length of a stone wall, testing how long it take for a snowball to melt at various places in your site, finding the hottest and coldest micro-locations, etc., etc. [g] Develop and include a well thought out hypothesis for which if the results were known we would have a better understanding of the site’s landscape natural history. Create a plausible, step-wise methodology for testing the hypothesis. ~~The Report~~ [a] Your report should be informative, easy and fun to use, filled with specific information and interpretation, and richly referenced. However you chose to assemble and present the report it should be engaging, attractively and informatively illustrated, and fact rich. Use your own creativity to present at least what is listed below. Whether you do a written report on paper or prepare a website, style your report to work well with the selected medium. Prepare your report as though it were for use by a local organization as the basis for further conservation and/or additional study. Expect it to be a substantial document or website. [b] It is important that you first determine the boundaries of your site and of your microsite. Once these are determined create by hand or computer base maps of your site and microsite, including the boundaries. Then use the base maps for the collection of information, for your analyses, for your interpretations, and for illustrating the site and microsite. Be sure you understand the simplicity of base maps and their utility … and then be sure to make use of them. These “plan-view” base maps will be in two dimensions and can be carried on site. You should also prepare three dimensional representations for your site and microsite (we will work on how to do this in class). Third dimension possibilities include a simple vertical dimension (i.e. upward into a canopy and the sky; downward into the earth or lake), time (e.g. historical scales), processes (e.g. sequential such as succession or cyclical such as seasons), diversity (e.g. complexity of life forms or causal factors), chance (e.g. biogeographical colonization, chaos theory as applied to regular irregularities in a landscape), etc. [c] You may choose a “layer-cake of knowledge” approach in your report, or you can use the “pin-hole camera” approach. In the layer-cake approach more and more information accumulates for an area, each adding another layer of information upon a basic framework, such as a topographic map. In the pin-hole camera approach, by 11 looking closer and closer at a very small feature (a rock, a frog, a seep) all the things that influence that feature become clearer and more evident. Ultimately the pin-hole camera approach is vastly more effective and comprehensive; whereas the layer-cake approach is commonly the first approach used. In the field of land use planning, general information for a region is complied in the layer cake format (GIS is good at this), but when a specific planning decision is required the pinhole (the specific decision) approach prevails ….. often bringing truth to the aphorism "the devil is in the details!" ~~Suggested contents and format~~ Note: The final copy is to be bound attractively and include a citable title page. Do not submit in a loose-leaf, three-ring binder. Appendixes and accompanying materials need to be clearly referenced in the main text. I. Introduction: (a) Locate the site within North America, New England/Vermont, and locally with reference to geography, physiognomy, geology, biogeomorphogy and community character, and relationship to surroundings. Use maps as appropriate. (b) State when you visited the site, and how much time was spent at each visit. II. The Site Today: Specifically describe and characterize the site as it is now. Use base maps to display features and their relationships. Illustrate with photos, drawings, sketches, etc. The reader or viewer of your report should have a good and informed picture of your site, even if they have never been there. Include at least the following aspects; other aspects will reveal themselves to you as you proceed. (a) In addition to your use of the base maps create one or more biogeomorphic site maps and vertical profiles along with descriptive text, tables and lists. Where it is not possible to determine information due to snow cover (masking soils, for example), overlying materials (obscuring bedrock, for example), etc., present probable features and character. (b) In addition to your maps and profiles, include a list of community types as per "Wetland, Woodland, Wildland." If you can't find suitable community types in that book (work hard to find them), create new community types and place in the community classification scheme as presented by Thompson and Sorenson. (c) Make an illustrated list of all the common and interesting trees at your site (if your site includes trees). Use the common or scientific names, or if you don’t know what the name is … make one up. Illustrate with a defining characteristic such as bark, leaf, nut, branching pattern, seeds, etc. The illustrations can be a photo you take or a drawing you do. (d) Describe the wildlife habitat provided by your landscape. Discuss whether your landscape is a biologic island, part of larger habitats, includes corridors, etc. Use your base maps whenever they can be helpful. (e) Include lists of vertebrates (mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians) that you actually detect (sight, sound, or sign) as well as those that likely occur there. (f) Describe, map, and discuss the location and movement of surface waters, and indication of ground waters (e.g. recharge areas, seeps, springs). Note features that tell of water levels and movement at other times of the year. Use your base maps here. 12 (g) Determine what human activities appear to occur at the site at various times of the year. Use your base maps as appropriate. (h) Document the signs and indications of previous human activities at the site. Speculate on the use and appearance of the site from pre-colonial times to the present. (i) Following the themes of the weather event assignment, describe the development, history, events, and effects of one or more weather phenomena affecting your site during the period of your study. III. Process and Patterns: (a) Describe and discuss what processes have shaped the physiognomy and bioecogeomorphology (note there are two concepts: “biogeomorphology” and “bioecogeomorphology” … we will discuss these in class) of the site. Include both natural and anthropogenic activities; refer to all the aspects describe in Section II above. Use as much supporting evidence from your site as you can. (b) Then speculate, to complete your stories about landscape shaping processes. [We will talk a lot about the relationships between pattern and processes during the course, from both theoretical and everyday perspectives.] This section will likely include the use of various time scales, and will overlap in various ways with section VI. IV. Microsite: (a) Use the same approach as II & III for your microsite. Since you will likely have selected your microsite for a particular reason, you should focus on that aspect … and then develop the relationships between the detail you present for the microsite and the broader information for the whole site. V. Timeline: (a) Tell the history of your site including several time scales. One part of the history begins either with the formation of Earth or the origin of the bedrock at your site. One time scale begins with the retreating ice of the last ice age. Yet another time scale begins with the arrival of Europeans to North America. You could begin another time scale with the first events documented at your site in its vegetation and human traces. There are even time scales that are contemporary: yearly, daily, and momentarily. At a bare minimum you should present timelines including the origin of the bedrock, the effects of recent glacial events, likely pre-settlement conditions, and the activities of people. (b) This section should be an integration of information gathered from the site and from our texts. If extracting a time line from a published source don’t just cut and paste into your report. Annotate the time line with evidence and examples from your site. (c) Speculate upon how the site will change in future time scales. VI. Testable hypothesis: [a] Develop and include a well thought out hypothesis for which if the results were known we would have a better understanding of the site’s landscape natural history. Create a plausible, step-wise methodology for testing the hypothesis. 13 A hypothesis is a declarative sentence that can be proven false or supported with testing. There are “cause-and-effect hypotheses”, which usually involved manipulative tests, and “correlative hypotheses”, which seek to show a correspondence among factors that is higher than randomness would predict. VII. Values: (a) In this section, present features that do or might hold values of importance to various individuals (including you). The values might be scientific (great place to study frogs), biodiversity (an excellent habitat for amphibians to flourish), recreational (fine spot to jog), aesthetic (quiet, cathedral-like forest), monetary (dollar value for logging or home-building), etc., etc. (b) You can present this section either in report form (i.e. a listing and discussion of values present), or as a personal essay, piece of your writing, poem, or any other appropriate medium. You could intersperse this aspect throughout via pictures, quotes, bits of verse, or the like at the beginning of sections, as sidebars, or another creative and communicative way. (Be sure to cite sources for all material used.) VIII. Cultural Features and Perspectives (optional): (a) In this optional section further embellish human involvement with your site. This might include an enriched representation of hunting, agricultural practices, sugaring, barn architecture (see attachment to this syllabus), vistas, spiritual sites, etc., that occur at your site. (b) You could also view your landscape not only from the distinctively Western view that prevails in sections I-VII above, but from the perspectives of Native Americans, Taoists, Bhopahs, or any other tradition. IX. References: (a) Include a full bibliography of all materials used, including maps (don't reject using a map if it is lacking citable information, just indicate from where you got the map). In a separate list include persons consulted. Remember, this is NOT a library or on-line research project! ….. so you should have only a few citations. More on where students have trouble with this assignment --- 1. Not working REALLY HARD to understand and document what is at the site, and what its past and present dynamics are. 2. Not finding and documenting via photos little (or big) examples that reveal the specialness and dynamics of the site. 3. Not taking ownership of becoming the people most familiar with the site. 4. Underutilizing sketches made, maps created, diagrams drawn and photographs taken in preparing the final report. 14 6. The On-site Group Presentation This oral presentation is similar to a site visit by a planning, zoning, or environmental board, conservation commission, or preservation organization prior to deliberations that will require study of a written document and finally a decision of some kind. Your job is to familiarize and richly inform the rest of us about your site and its principal features. It is exceedingly helpful if you bring friends for the presentation. They always have a great time, and their questions significantly aid conversation, clarity, and tangents! Your presentation should be very well planned, full of useful site-specific information and context Plan a 2-3 hour tour of the significant highlights of the site, including time for discussions, questions, and walking about the site. Interpret the landscape as per your written or website report. Expect there to be lots of interactive conversation throughout the tour … so make sure you are well prepared, thus to help keep the tour on track. For use during the tour provide three copies of an informative and well done packet containing various maps of the landscape, other illustrative materials as helpful, and a thoughtful provisional list of vertebrate animals that might be seen. Include as well your particular hypothesis and proposed methodology for its testing. These will be used those of us who constitute your audience. DO NOT FORGET TO DO THIS! Equally involve all members of your team. Be polished and efficient, with a specific agenda, crisp descriptions and interpretations, broad perspectives, specific examples, and an evident conclusion. Expect lots of interruptions and tangents created by your audience. Where students have trouble with this assignment --- 1. Not following the instructions above!! 2. Not having a plan for the outing. 3. Not creating a story-line. 15 Possible final project sites (there are many, many, many, many more!) Bolton Notch Cliffs *** Charlotte Wildlife Park Colchester Pond Shores * Delta Park * Geprag Community Park * Indian Brook Caves ** Indian Brook Ravine * Joiner Brook *** LaPlatte River Marsh – Central * LaPlatte River Marsh – NE Side * LaPlatte River Marsh – W Side LaPlatte River/Falls/Cliffs/Slump * Lone Rock Point – N * Lone Rock Point – S *** Mt. Philo – Summit Mt. Philo – W * Mud Pond - East side *** Niquette Bay State Park – S Niquette Bay State Park – Upper * Pease Mountain – upper Pease Mountain – S Red Rocks Park Salmon Hole * Shelburne Bay Park – Allen Hill * Shelburne Bay Park - S * Shelburne Pond Nat. Area – SW * Shelburne Pond Nat. Area – W Sunderland Brook Ravine Williams Woods * Woodside Park * Transportation: c=car b=bike Trans. to site c c c c /b c c c c c/k/b c/b c/b c/b c/b/p c/b/p c c c c c c c c/b/p w/b c/b c/b c c c c c/b p=city bus Minutes to site 40 25 30 25 25 30 30 40 40 30 25 25 25 30 40 40 25 35 25 30 30 20 20 40 25 25 35 20 35 25 Town Bolton Charlotte Colchester Colchester Hinesburg Colchester Colchester Bolton Shelburne Shelburne Shelburne Shelburne Burlington Burlington Charlotte Charlotte Williston Colchester Colchester Charlotte Charlotte S. Burlington Burlington Shelburne Shelburne Shelburne Shelburne Colchester Charlotte Essex k=kayak or canoe w=walk Moist, steep montane cliffs; rocky forest land; fire community; wetlands Abandoned pasture; wetlands; stream; facing Lake Champlain and Adirondacks Fields, woodlands, ledge along shores of small lake Deltaic beaches, levees, wetlands at mouth of Winooski River at Lake Champlain Abandoned hilly farmland and farm site Incised meandering stream; caves Meandering stream incised in glacial delta; springs and seeps; beaver; wetland Bouldery, bubbling montane stream; steep wooded slopes Wetland complex among stream meanders by Shelburne Bay of Lake Champlain River, wetlands, and floodplain forests along LaPlatte River by Lake Champlain Wetlands and old fields adjacent to LaPlatte River by Lake Champlain Cliffs, wetlands, floodplains, rocky white water ravine, meandering river Mixed forests; ravines; cliffs; sinkholes; Lake Champlain shoreline Extensive lake cliffs; lake shore; rich forests; floodplain Mixed forests and park facilities on summit dome of Mt. Philo Mixed forests on steep slopes and cliffs on W face of Mt. Philo Rolling forest land; bog and wetland margin; beaver Hilly diverse forests; rocky shore; small stream and delta on Malletts Bay Hilly diverse forests; rich ledges; wee wetlands Mixed successional forests on slopes and ledges Mixed successional forests on slopes and ledges; open, dry ledges Diverse mixed forests; lake-side cliffs; cliff shores River; river ledges; mid-channel island; river banks and cliffs; shores Complex geology; mixed forests on steep slopes and ledges; Shelburne Bay shore Diverse forests and oldfield succession; seeps; Shelburne Bay shore Complex old-field succession on slopes, ledges, cliffs; pond shore; wetland margin Complex old pasture land on ledge and rich soils surrounded by diverse wetlands Meandering stream incised in glacial delta; springs and seeps; beaver; wetland Clay plain forests; meadering stream; wetland; windthrown trees Wetlands and floodplain adjacent to Winooski River *= sites chosen by recent groups "Minutes to site" approximates time from campus and includes walking from vehicle to beginning of field site Notes on Barns Although in the Champlain Basin well over 98% of all barns built and used since the 1780’s no longer exist, there are still many to be found by the careful investigator. The barns retain in their construction and design abundant clues to land use and character since the first days of permanent European settlement in the Basin. Thus, they are powerful resources for the landscape natural historian. For example, barns which are composite buildings with multiple additions spread out over 200 years or more identify locations with good soils, agriculturally favorable soils, moderate climates, and available fresh water. In the Champlain Valley expect the following, generally chronological sequence of barn types and attributes, beginning from the late 1700's to the present. Realize that many barns have been highly modified, moved, joined with other barns, or demolished. Visser's Field Guide to New England Barns and Farm Buildings will be very helpful with identifying features, uses, and dates. This sequence (see below) focuses on barns used primarily for dairy cattle, hay and grain, and/or working horses (or oxen). From 1840 till shortly after the Civil War there were many barns built or modified for sheep and for horse breeding; most of these barns have been dismantled or were converted to dairy cattle. Beginning in the 1970's, and expanding rapidly in the late 1980's to the present, many horse barns have been built. This trend is especially true in proximity to larger villages and cities. These are typically one story tall, broadly rectangular in floor plan, and may include a "show" area inside or adjacent to the barn. Other recognizable barns of size were built to house chickens, sheep, and occasionally fox. A variety of other animals housed at one time or other include pheasants, hogs, llamas, rabbits, muskoxen, mules, goats, turkeys, deer, elk, duck, geese, donkeys, emus, beef cattle and certainly others. Barns likewise have served to house and process various plant products such as tobacco, dried herbs, and root crops. The term “barn” is also used for buildings to shelter all sorts of land vehicles; for example in the world of Greyhound and Vermont Transit a “car barn” is the building in which busses are stored and worked upon. An abbreviated sequence of Champlain Basin major cattle barn types since the late 1700’s a) b) c) d) e) f) g) h) i) j) k) l) m) n) o) p) Colonial English barns with threshing floor and eave-sided doors Colonial English barns with underfloor for cows, often built on a slope for direct entry each floor Colonial English barns with aesthetic touches or embellishments English-style barns with gable-front doors English-style barns with gable-front doors and barn banks or "high-drives" Extended and joined English barns [note that during this period of modified English style barns cupolas appeared] Round and polygonal barns Highly embellished, Victorian stylized barns; silos are introduced Gambrel, hipped and Gothic roofed barns Monitor barns Hayloft and stanchion barns with separate milk house Hayloft and stanchion barns with attached milk house Hayloft and stanchion barns with low-roofed stanchion addition [bunker silos are introduced, as are liquid manure silos and pits] Hayloft and stanchion barns with milking parlors Single-story, often open-walled free-stall barns with separate or attached milking parlor [demise of cylindrical silos, advent of round bales and plastic packaged bales] Multiple unit free stall barns with separate calf barns or calf-house villages; large, road-faced gabled milking parlors with picture windows Some Particular Learning Objectives These objectives can be attained by attentive participation in the class, the willingness to take good notes and practice skills, studying in the out-of-doors between class sessions, using our texts and handouts, and hard work on the individual and group activities. Throughout the course we will draw from a number of specific disciplines and interdisciplinary approaches such as botany, geology, soil science, agroecology, hydrology, wildlife biology, zoology, forestry, history, weather, ecology, landscape ecology, and natural history. By the end of the course, at the intermediate college level you should be able to accomplish a variety of these goals: see landscape features at a variety of scales and in a variety of dimensions and timeframes understand the rudimentary geologic history of the Champlain Basin understand basic geomorphological features and processes that shape today's Champlain Basin identify influences of bedrock and geomorphological features upon other landscape components identify several of the most common local rocks, bedrock features, and glacial landforms identify a number of lakeshore, stream and river geomorphic and hydrological features recognize the range of soil types and parent materials found in Chittenden County understand some relationships among soil type, soil genesis, vegetation and animal life formulate simple causal and correlative hypotheses discuss natural history aspects of at least 25 common plants in the Champlain Basin identify and characterize a variety of the natural communities of the Champlain Basin anticipate and locate recharge areas and seeps and/or springs in various landscape types understand where snow goes when it melts and where water goes when it rains see signs of the transition from season to season (from the first to last days of the course) recognize events that happen at a site during seasons other than the present season identify at least 10 animal species by call and 20 by sight or sign decipher imprints of human history on local landscapes identify major weather phenomenon and the local variations visible in our viewscape identify effects of weather phenomenon and climatic variation in landscape features locate and interpret a variety of signs of local wildlife species (at least 15 species) understand how to stalk and see wildlife see and interpret the influence of some natural "disturbance" regimes on landscapes determine and interpret aspects of the natural and human history of a local site select and use “unifying themes” and “frameworks of analyses” to assess specific sites recognize the ages of agricultural activity through the interpretation of stone walls, barn architecture, field size and location, and other similar features identify three or more invasive exotic plant and/or animal species and understand some of their influence on regional and local ecology 18 Categories of animal signs This list of animal signs is certainly not complete. Help me add to it! Tracks Trails Landings Midden Browse Rubbings Scat Scent Latrines Scratches Caches Sweat Gnawings Footsteps Slitherings Scratching Beds Lookouts Roosts Dens Carrion Digs Nests Waterings Haul-outs Sheddings Breath Pellets Chippings Calls Breathing Cries Carcasses 19