Summary Statistics

advertisement

Summary Statistics

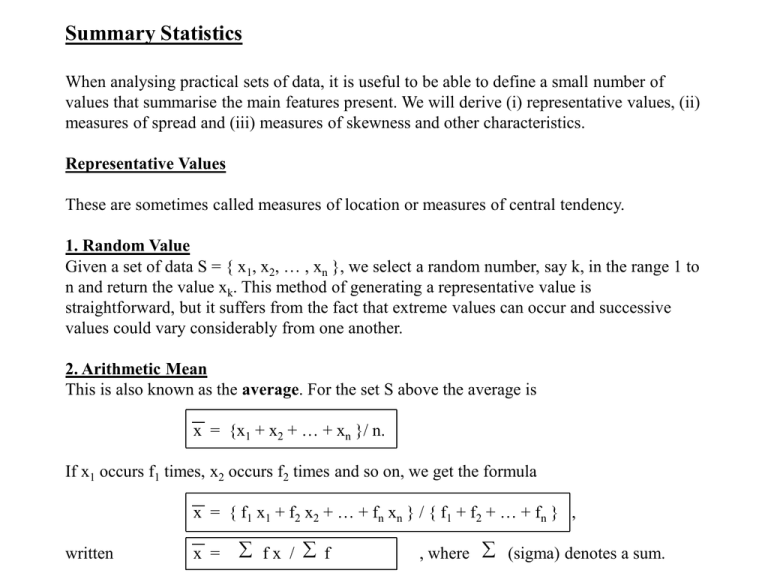

When analysing practical sets of data, it is useful to be able to define a small number of

values that summarise the main features present. We will derive (i) representative values, (ii)

measures of spread and (iii) measures of skewness and other characteristics.

Representative Values

These are sometimes called measures of location or measures of central tendency.

1. Random Value

Given a set of data S = { x1, x2, … , xn }, we select a random number, say k, in the range 1 to

n and return the value xk. This method of generating a representative value is

straightforward, but it suffers from the fact that extreme values can occur and successive

values could vary considerably from one another.

2. Arithmetic Mean

This is also known as the average. For the set S above the average is

x = {x1 + x2 + … + xn }/ n.

If x1 occurs f1 times, x2 occurs f2 times and so on, we get the formula

x = { f 1 x1 + f 2 x2 + … + f n xn } / { f 1 + f 2 + … + f n } ,

written

x =

fx / f

, where (sigma) denotes a sum.

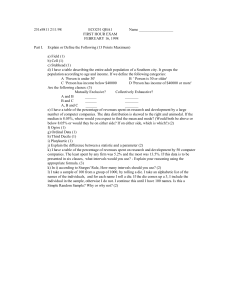

Example 1.

The data refers to the marks that students in a class obtained in an examination. Find the

average mark for the class. The first

point to note is that the marks are presented as Mark

Mid-Point Number

ranges, so we must be careful in our

of Range

of Students

interpretation of the ranges. All the intervals

xi

fi

f i xi

must be of equal rank and their must be no

gaps in the classification. In our case, we

0 - 19

10

2

20

interpret the range 0 - 19 to contain marks

21 - 39

30

6

180

greater than 0 and less than or equal to 20.

40 - 59

50

12

600

Thus, its mid-point is 10. The other intervals 60 - 79

70

25

1750

are interpreted accordingly.

80 - 99

90

5

450

Sum

50

3000

The arithmetic mean is x = 3000 / 50 = 60 marks.

Note that if weights of size fi are suspended

from a metre stick at the points xi, then the

average is the centre of gravity of the

distribution. Consequently, it is very sensitive

to outlying values.

x1

x2

f1

x

xn

fn

f2

Equally the population should be homogenous for the average to be meaningful. For

example, if we assume that the typical height of girls in a class is less than that of boys,

then the average height of all students is neither representative of the girls or the boys.

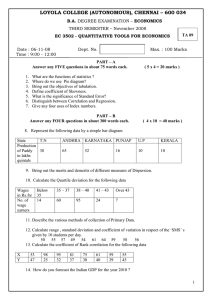

3. The Mode

Frequency

50

This is the value in the distribution that occurs

most frequently. By common agreement,

it is calculated from the histogram using linear

interpolation on the modal class.

13 20

25

13

The various similar triangles in the diagram

generate the common ratios. In our case,

the mode is

60 + 13 / 33 (20) = 67.8 marks.

20

12

6

2

20

5

40

60

80

40

60

80

100

4. The Median

Cumulative

50

This is the middle point of the distribution. It

is used heavily in educational applications. If

{ x1, x2, … , xn } are the marks of students in a

class, arranged in non-decreasing order, then 25.5

the median is the mark of the (n + 1)/2 student.

It is often calculated from the ogive or

cumulative frequency diagram. In our case,

the median is

60 + 5.5 / 25 (20) = 64.4 marks.

Frequency

20

100

Measures of Dispersion or Scattering

Example 2. The following distribution has the same

arithmetic mean as example 1, but the values are more

dispersed. This illustrates the point that an average

value on its own may not adequately describe a

statistical distributions.

To devise a formula that traps the degree to which a

distribution is concentrated about the average, we

consider the deviations of the values from the average.

If the distribution is concentrated around the mean,

then the deviations will be small, while if the distribution

is very scattered, then the deviations will be large.

The average of the squares of the deviations is called

the variance and this is used as a measure of dispersion.

The square root of the variance is called the standard

deviation and has the same units of measurement as

the original values and is the preferred measure of

dispersion in many applications.

Marks

x

Frequency

f

10

30

50

70

90

Sums

6

8

6

15

15

50

fx

60

240

300

1050

1350

3000

x6

x5

x4

x3

x2

x1

x

Variance & Standard Deviation

s2 = VAR[X] = Average of the Squared Deviations

= S f { Squared Deviations } / S f

= S f { xi - x } 2 / S f

= S f xi 2 / S f - x 2

, called the product moment formula.

s = Standard Deviation = Variance

Example 1

f

x

2

10

6

30

12

50

25

70

5

90

50

fx

20

180

600

1750

450

3000

f x2

200

5400

30000

122500

40500

198600

VAR [X] = 198600 / 50 - (60) 2

= 372 marks2

Example 2

f

x

6

10

8

30

6

50

15

70

15

90

50

fx

60

240

300

1050

1350

3000

f x2

600

7200

15000

73500

121500

217800

VAR [X] = 217800 / 50 - (60)2

= 756 marks2

Other Summary Statistics

Skewness

An important attribute of a statistical distribution relates to its degree of symmetry. The

word “skew” means a tail, so that distributions that have a large tail of outlying values on the

right-hand-side are called positively skewed or skewed to the right. The notion of negative

skewness is defined similarly. A simple formula for skewness is

Skewness = ( Mean - Mode ) / Standard Deviation

which in the case of example 1 is:

Skewness = (60 - 67.8) / 19.287 = - 0.4044.

Coefficient of Variation

This formula was devised to standardise the arithmetic mean so that comparisons can be

drawn between different distributions.. However, it has not won universal acceptance.

Coefficient of Variation = Mean / standard Deviation.

Semi-Interquartile Range

Just as the median corresponds to the 0.50 point in a distribution, the quartiles Q 1, Q2, Q3

correspond to the 0.25, 0.50 and 0.75 points. An alternative measure of dispersion is

Semi-Interquartile Range = ( Q3 - Q1 ) / 2.

Geometric Mean

For data that is growing geometrically, such as economic data with a high inflation effect, an

alternative to the the arithmetic mean is preferred. It involves getting the root to the power

N = S f of a product of terms

Geometric Mean = N x1f1 x2 f2 … xk fk