FORMAL STUDY OF ANYTHING BEGINS ... “TERMS” AND CREATING A VOCABULARY.

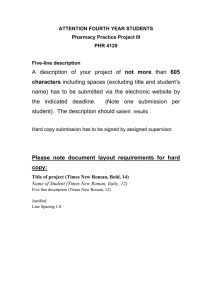

advertisement

FORMAL STUDY OF ANYTHING BEGINS WITH DEFINING “TERMS” AND CREATING A VOCABULARY. HOW DO WE DEFINE THE WORD “RELIGION”? In order to study something effectively, the object of study must be clearly identified. One important part of this is the definition of terms. The study of religion is no exception. The varied uses of the word "religion" and the variety of human thoughts, feelings and attitudes about religion require that we identify as precisely as possible how the word will be used in this course. To "de-fine" means to "put a limit" on something, i.e., to make it “finite,” “limited.” Definitions are tools used to direct how something is talked about by helping persons agree about what they are discussing. Otherwise our talking can be at cross purposes. We won’t know what we are talking about. There and many definitions and descriptions of the word “ religion”? Where did the word “religion” come from? No one is quite sure where the modern concept of religion came from or exactly what it is supposed to mean. While this may not matter to many people, for governments, schools, and courts, this lack of clarity in meaning and use can create serious difficulties. We do know that the English word “religion” is derived from the Latin noun religio, but it is not clear which of three verbs the noun is most closely allied with: relegere ("to turn to constantly" or "to observe conscientiously"); religari ("to bind oneself [back]"); and reeligere ("to choose again"). Each verb, to be sure, points to three possible religious attitudes, but in the final accounting a purely etymological probe does not resolve the ambiguity (McBrien 359). This confused situation suggests that the modern use of the term "religion" is probably not rooted in the distant past but likely represents a concept (or set of concepts) of rather recent vintage. In other words, our modern idea of “religion” is a modern idea. Before the Protestant Reformation, the idea of "religion" or "religious life" pertained in particular to people who lived a life under religious vows--monks and nuns. This life was, and still is in the Roman Catholic understanding, distinguished from "secular life," that is, life "in the world" as opposed to life in a community of people under religious vows. One can speak of "religious" and "secular" clergy, that is, of priests who belong to a religious order (Benedictines, Franciscans, Dominicans, Jesuits, et.al.) as distinguished from those who live ordinary lives in society like most people do. How did the meaning of “religion” develop in the European world? Since the Roman Emperor Constantine had legalized (some would say co-opted) Christianity in the fourth century, there had been a strong admixture of politics in church life. The church came under imperial protection and even became a part of the operation of the Roman state. It has tended to stay that way in countries under Byzantine (Eastern Roman Empire) influence. Even during the Soviet period, the Russian Orthodox Church remained under government supervision. After Constantine moved the capital of the Roman Empire to the East, the Western end of the empire gradually fell apart under pressure from barbarian invaders. As the state progressively disappeared, the Roman Church was left holding the few organizational and administrative cards that still existed. The bishops of Rome, in particular, set into motion the long mission effort from which modern Western European nations would emerge. Eventually, the barbarians were running everything, including the church. The state started to emerge again, to some degree under church sponsorship, as we see, for example, in the coronation of Charlemagne as Holy Roman Emperor in 800 A.D. But this whole process took many centuries. By the sixteenth century, the state had considerable power. The Holy Roman Empire persisted, but other kinds of states were emerging, too. During the Protestant Reformation, another kind of meaning emerged. In many ways, the Reformation was an adjustment of church life to take that into account. It was difficult to imagine what to do with people who refused allegiance to Pope and Emperor. After a good deal of battling, the Peace of Augsburg (1555) was achieved which allowed individual princes to determine whether the territories they governed would be Lutheran or Catholic. The "religion" of the prince would determine the "religion" of the territory. In 1648, the Peace of Westphalia extended this arrangement to the Calvinists. The idea spread from there. The Constitution of the United States, with its first amendment separation of church and state, raises some interesting problems in this regard. The so-called “separation clause” says that Congress will not establish a religion or interfere with its practice. This was a radical innovation in human experience and practice. It separated “religion” from sponsorship or control by the state. Today people often say they are “spiritual” and not “religious,” a way of speaking that reflects this American approach. A serious problem is the fact that this idea of “religion” is basically a European idea that is not shared by most of the rest of the world. This alone accounts for much of the misunderstanding and even conflict between Western nations and persons in Islamic nations where “separation” is not a popular idea. This is a pretty thin sketch of a complex history, but it gives some idea of how "religion" came to mean something done or adhered to in terms of some politically recognized organizational set-up such as a church or other body (e.g., a Buddhist temple, a Jewish synagogue, etc.) could be understood as "religion." From there, the meaning was extended further to include practices that were explicitly non-institutional: people could be "religious" without joining up with anybody else. Beyond the political understanding, there gradually emerged also various academic understandings of “religion.” From the political use, "religion" came to be something that scholars could study quite apart from any personal commitment or involvement themselves. The word "religion" is used in various ways by scholars from many fields, so there can be many different questions and approaches to the study of "it." One could study “Hinduism,” “Judaism,” “Catholicism,” or many other “-isms” as more or less discrete and closed systems of belief and practice. Today scholars are beginning to point out the difficulties and limitations of this approach. Below is a list of examples of these different approaches and understandings. It is by no means a complete list but only a sampling. As you read through the list, see if you can identify any characteristics of the defining process. How do you think the academic discipline of an author might make a difference in how he or she looks at "religion"? Different disciplines ask different questions, and therefore they need distinctive ways of using words. They develop distinctive vocabularies and definitions. Some of the names will probably be familiar. 1. Religion is what you get when you investigate striking human phenomena to find the ultimate vision or set of convictions that gives them their sense. (Carmody and Carmody) 2. Religion is human involvement with sacred sanction, vitality, significance, and value. This involvement is mediated through symbolic processes of transformation. Religion is expressed in and transmitted by cultural traditions that constitute systems of symbols. (Niels Nielsen) 3. A belief in spiritual beings. (Tylor) 4. Religion can be defined as a system of beliefs and practices by means of which a group of people struggles with the ultimate problems of human life. It is the refusal to capitulate to death, to give up in the face of frustration, to allow hostility to tear apart one's human associations. (J. Milton Yinger) 5. Religion, in the largest and most basic sense of the word, is ultimate concern. And ultimate concern is manifest in all creative functions of the human spirit. (Paul Tillich) 6. Religion is a system of significance that provides humans with a way of getting a handle on what is ultimately real. (Roger Schmidt) 7. Religion is a complex form of human behavior whereby a person (or a community of persons) is prepared intellectually and emotionally to deal with those aspects of human existence that are horrendous and nonmanipulable. (William Calloley Tremmel) 8. Religion is what an individual does with his own solitariness. (Alfred North Whitehead) 9. The common element of religion (is) the consciousness of ourselves as absolutely dependent. (Friedrich Schleiermacher) 10. The recognition of our duties as divine commands. (Immanuel Kant) 11. (Religion is) an illusion, a neurosis born of the need to make tolerable the helplessness of man, and built out of the material offered by memories of the helplessness of his own childhood and the childhood of the human race. (Sigmund Freud) 12. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the sentiment of the heartless world, the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people. (Karl Marx) 13. The idea of society is the soul of religion... collective sentiments-fixing themselves upon external objects. (Emil Durkheim) 14. Man is the beginning of religion, the center of religion, the end of religion.(Religion) is the dream of the human spirit. (Ludwig Feuerbach) 15. (Religion is) a sum of scruples which impedes the free exercise of our faculties. (Salomon Reinach) 16. Religion is (1) a system of symbols which acts to (2) establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in (people) by (3) formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and (4) clothing these conceptions with such an aura of factuality that (5) the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic. (Clifford Geertz) 17. Religion is a means to ultimate transformation. (Frederick J. Streng) Although we will not spend time on the matter here, a claose look at these definitions reveals that there are various kinds of definitions. Here are some categories of these different kinds: I. Descriptive Definitions: This kind of definition tells how the word is used by some person or group. Use is the basis for this kind of definition. Example: "Religion is whatever any person or group of persons calls religion." II. Normative Definitions: This kind of definition is based on some norm, on what someone thinks it "ought" to be. The word is used to point to that "ought to be" or "should be." Example: "Religion is whatever any person feels it should be." (Here feeling is the norm.") III. Essential Definitions: This kind of definition is based on some essential quality or characteristic that the definer specifies. Example: "Religion is someone's way of relating to the transcendent." IV. Functional Definitions: This kind of definition is based on something that the thing under study does. The function in question might be political, social, economic or whatever. Example: "Religion provides the basis of society, the glue of society." Into which kind of definition does each in the listing above fit?