GLOBALIZATION AND FIRM DYNAMICS IN THE ISRAELI SOFTWARE

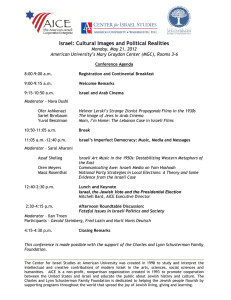

advertisement