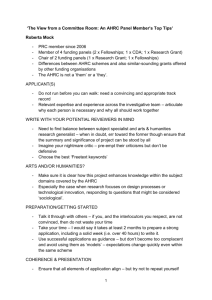

How to make Successful (AHRC) RG bids Practice-led proposals

advertisement

How to Make Successful AHRC Grant Bids (incl. practice-led proposals) From a practitioner’s point of view Adapted from a presentation prepared by Professor Stephen AR Scrivener, University of the Arts London Introduction writing a good proposal writing for a funding context writing a good practice-based proposal relevant to a proposal, illustrated through AHRC. Writing from your own perspective This idea is really good. I really know my stuff. What matters to me matters to them – the funders. Multiple perspectives the proposer’s, of course the funder’s the discipline’s (peer reviewers) the panel’s. Understanding this context will help you to write a better proposal, i.e., one that does more justice to your idea …so now the funders… AHRC’s Mission Promote and support the production of world-class research in the arts and humanities. Promote and support world-class postgraduate training designed to equip graduates for research or other professional careers. Strengthen the impact of arts and humanities research by encouraging researchers to disseminate and transfer knowledge to other contexts where it can make a difference. Raise the profile of arts and humanities research and to be an effective advocate for its social, cultural and economic significance. Mission drives programmes Responsive mode research schemes: • • • • Fellowships Research Grants Research Networking Scheme Follow-on Funding Scheme Strategic Initiatives: • Themes …and now to applying understanding of the context… Choosing the right programme for your purposes Which scheme? And which route? Fellowship? • Standard Route? • ECR? Research Grant? • Standard Route? • ECR? Or another scheme??? Before starting to fill in a proposal form: read the Call documents read the Scheme Guidance read the Funding Guide read the T&Cs Background • have a look at applications funded through the scheme • have a look at the previous data • have a look at case studies Relevant AHRC web pages Make sure that you meet the aims or criteria e.g., Fellowships Aims: • to provide time for focused individual research as well as collaborative activities • to support research projects which have the potential to generate a transformative impact on their subject area and beyond • to develop capacity for research leadership in the arts and humanities • to sustain and enhance research capacity in areas which may currently be undersupported for a variety of reasons • to support the AHRC in delivering its strategic priorities and national capability needs. Make sure you are eligible e.g. Fellowships: The applicant: must be a salaried member of staff at the Research Organisation (RO) submitting the proposal. will have been employed by the RO for at least a year before the date of submission of the proposal. must have a contract of employment, as confirmed by their RO, that extends beyond the duration of the proposed Fellowship that allows them to complete the work outlined in the proposal and is consistent with the RO’s commitments to support the applicant’s longer term career development beyond the end of the Fellowship. Furthermore: previous holders of an AHRC Fellowship are not permitted to submit a proposal to this scheme until at least one year after the end of the previous Fellowship. unsuccessful applicants are not permitted to submit a new (different) application under the scheme within one year of the announcement of the outcome of their previous application. Make sure it is research in AHRC’s terms To fit the Council’s definition of research, a proposal must: define a series of research questions or problems that will be addressed in the course of the research. It must also define its objectives in terms of seeking to enhance knowledge and understanding relating to the questions or problems to be addressed. specify a research context for the questions or problems to be addressed. It must specify why it is important that these particular questions or problems should be addressed; what other research is being or has been conducted in this area; and what particular contribution this particular project will make to the advancement of creativity, insights, knowledge and understanding in this areas. specfiy research methods for addressing questions or problems. It must state how,…, you will seek to answer the questions… It should explain the rationale for the chosen research methods and why these are thought to provide the most appropriate means to answer the questions. Read the scheme guidance AHRC provides detailed guidance to applicants for each scheme know the relevant guidance well, don’t rely on the application form e.g., guidance explains how your proposal will be assessed the significance and importance of the project the appropriateness, etc., of research methods and timescale ability of applicant(s) to complete project (track record) value for money appropriateness of dissemination for certain programmes, the extent to which proposal meets the Council’s strategic priorities. Read the scheme guidance, continued e.g., it explains what should be in the case for support what are the aims and objectives of your research?... what are the research question(s) or problem(s)?... what is the research context for your project?… what research methods will you be adopting?... Look at how the proposal will be assessed The reviewer’s form is an evaluation of how criteria are assessed AHRC reviewer’s form looks at: the quality and importance of the project people management outputs and dissemination value for money strengths and weaknesses The guidance to assessors explains these things in detail. So now you’re ready to write the proposal Proposal All that could be described the field of inquiry the research methods employed in the field the field’s practical understanding of research practice the proposal is an argument in shorthand therefore, communication, communication, communication. What does the shorthand need to convey that you understand the field of inquiry that you have made a case for there being a lack of understanding that you have explained the significance of this lack that you have shown how the research questions/problems follow from and if answered/solved will fill this lack that you have a plan for answering the identified questions/problems that you know what methods you will use and why they are appropriate that you are realistic about what is achievable within the timescale that you have a team that can take the project forward. Be kind to panellists and reviewers The reviewers will be experts in the field, the panellists probably won’t be. The proposal needs to stand out - it needs to be a strong idea. The proposed research is the primary consideration. As early as possible state the idea, explain why it needs to be tackled and estimate its impact - be bold. Remind the reader of the above at appropriate points. At key points remind the reader what you have told them and tell them what you are going to tell them, in particular explain significance. Tell the reader what you want them to understand (explain why). Use simple language and language construction. And let your kindness continue Write so the reader can get it in one pass – avoid the reader having to go back through something to understand it. Don’t assume the reader is an expert in the subject. Don’t have too many aims or objectives, the reader won’t have time to stitch loads of objectives together with methodology, outcomes etc. Make sure that the research methods and stages of work will yield these aims and objectives, explain the connection: ? Objective Task Method Method And continue… Structure the proposal logically so that the reader doesn’t have to wait to see the significance of something said earlier, .e.g, don’t explain how you are going to do something before saying why you want to do it. Think of all the reasons for attacking your proposal and rebuff them. Better still, get someone else to look at it as a ‘critical friend’. There are people in your RO who can help, e.g. Research Office seek their advice. …and to the process… Evaluation: Panels comprise diverse experts All panels are non-standing and convened ad-hoc. Two types of panel: moderating and assessment. Moderating panels (e.g.): Fellowships Panel Research Grants Panels: A, B, C and D Assessment panels (e.g): • CDAs • Themes Large Grants – outline proposals Panels Moderating panels: • make funding recommendations for most schemes, including Research Grants and Fellowships, with open deadlines. • make judgments on the applications on the basis of the feedback from the peer reviewers and PI response. Panel members’ do not reassess the applications when deciding the final grade. • assign final grades against the scheme criteria and rank proposals in order of priority for funding. The rank ordered list agreed by the Panel forms the funding recommendation for AHRC. Assessment panels: • members assess the application • members assign a suggested grade against the scheme criteria, normally prior to the meeting. • the panel meets to discuss the pre-assigned grades, agree final grades and rank proposals in order of priority of funding. The rank ordered list agreed by the Panel forms the funding recommendation for AHRC. Evaluation: many people with varied expertise peer reviewers selected, as far as possible, from the AHRC Peer Review College an application is sifted out if it receives two or more reviews giving it an unfundable grade (1-3) application, reviews and the PI response forwarded to panel panellists agree final grade and rank proposals in order of priority for funding final funding decision rests with the AHRC. Evaluation: time is of the essence panellists receive a lot of material the application material reviews and PI responses technical plan (where appropriate) Contextualising assessment typically between 5 and 15 proposals to consider for each panel meeting typically eighteen working days between receiving panel material and panel meeting panellists need to set time aside to prepare for meeting to familiarise themselves with the proposals proposals have 2 Introducers and possibly a Reader all panellists, apart from the Chair, will be assigned as Introducer 1 or 2, and possibly Reader, for a number of proposals introducers should grade and comment on all of the proposals they are introducing in advance of the meeting. …and now to the practice-led proposal… Problems in writing practice-led proposals research questions and problems context research methods How a reviewer might look at practice-based proposals Has the applicant described the issues, concerns and interests stimulating the work? shown that the issues, concerns and interests reflect cultural preoccupations? shown that the response to these stimulants is likely to be culturally original? made clear the relationship between the artefact(s) to be realised and those issues, concerns, and interests? explained their likely originality indicated the knowledge, learning or insight that will result from the programme of work? provided an account of method that suggests a self-conscious, systematic and reflective practitioner? Summary advice articulate the research questions and research methods understand the overall funding context choose the right programme for your research make sure that you meet the aims or criteria understand what is expected and how this will be assessed recognise that your proposal must be transparent understand how the proposal will be read, both in terms of time and shorthand recognise that success is all about communicating efficiently. Further details on practice-based research papers by Professor Stephen Scrivener Further details on practice-based research papers by Professor Stephen Scrivener Scrivener, S.A.R. (2001) Reflection in and on Action and Practice in Creative-production Doctoral Projects in Art and Design. Working Papers in Design, 1. http://www.herts.ac.uk/artdes/research/papers/wpades/vol1/scrivener2.html (accessed 20/6/2003) Scrivener, S.A.R. (2002) Characterising creative-production doctoral projects in art and design. International Journal of Design Sciences and Technology, 10 ( 2), 25-44. (appeared 2004) Scrivener, S.A.R. (2002) The art object does not embody a form of knowledge. Working Papers in Design, 2. http://www.herts.ac.uk/artdes/research/papers/wpades/vol2/scrivenerfull.html (accessed 20/6/2003) Scrivener, S.A.R. & Chapman, P. (2004) The practical implications of applying a theory of practice based research: a case. Working Papers in Design, 3. http://www.herts.ac.uk/artdes1/research/papers/wpades/vol3/ssabs.html (accessed 6/12.04) Scrivener, S A R (2009) “The roles of art and design process and object in research”. In Reflections and connections: On the relationship between creative production and academic research, edited by Nithikul Nimkulrat and Tim O’Riley. [ebook] Helsinki: University of Art and Design Helsinki, 69-80. Scrivener, S.A.R. (2011) Transformational practice: on the place of material novelty in artistic change. In The Routledge companion to research in the arts, edited by Michael Biggs and Henrik Karlsson, Abingdon, Oxford: Routledge, 259-276 Scrivener, S A R (2011) “Part 1: Reflections on interactive art and practitioner research: establishing a frame.” In Research and the Creative Practitioner, edited by Linda Candy and Ernest Edmonds. Faringdon, Oxfordshire: Libri Publishing, 6072. Scrivener, S A R (2011) “Part 2: Reflections on interactive art and practitioner research: interpretation.” In Research and the Creative Practitioner, edited by Linda Candy and Ernest Edmonds. Faringdon, Oxfordshire: Libri Publishing, 305-323. Scrivener, S A R & Zheng, S. (2012) “Projective artistic design making and thinking: the artification of design research”, Contemporary Aesthetics, Special Volume 4, http://www.contempaesthetics.org/newvolume/pages/article.php?articleID=638Zheng 2008 (accessed January 16, 2013).