Financial Liberalization and External Shocks in the Malaysian Economy 1

advertisement

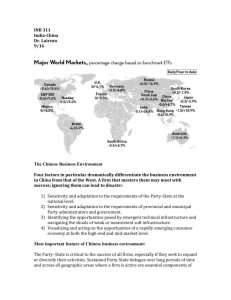

Financial Liberalization and External Shocks in the Malaysian Economy 1 Rajah Rasiah, Miao Zhang University of Malaya, Malaysia 2 Outline 1. Introduction 2. Liberalization to Attract FDI 3. Heavy Industry Promotion behind External Exposure 4. Return to Export-orientation 5. The Asian Financial Crisis 6. Capital Controls 7. Revival of Deregulation 8. Conclusions 3 1. Introduction 1. Keynes (1936) argued lucidly that markets are inherently imperfect; and the relationship between economic agents are often asymmetric (Stiglitz, 2009) 2. Keynesians call for interventions to ensure stability in both currency and capital markets so that the real economy is not subjected to turbulence. The call for this has become strong especially after 2007-08 global financial crisis 3. Malaysian economy fluctuated in a volatile manner as a consequence of heavy dependence on the primary commodities of rubber and tin; 4. fixed exchange rate mechanism shielded its incipient economy from externally driven financial bubbles until 1971 when the fixed exchange rate mechanism was abandoned after the United States withdrew the dollar and depreciated it. 5. Ringgit was introduced in 1975 6. Exchange rate began to fluctuate since 1973 when BNM withdrew from the currency union with Brunei and Singapore-- Keynesian exchange rate instruments were largely abandoned 7. Malaysian has had a mixed experience with financial liberalization with capital controls introduced between 1998-2005 being the only time when a serious attempt was made by the government to regulate the financial market. 8. This paper presents an analytical assessment of deregulation in the financial market with its consequent impact on the real economy over the period 1960s till 2014. 4 2. Liberalization to Attract FDI —1970s Behind interventions through NEP, the liberalization of manufacturing targeted at attracting FDI for stimulating job creation, no significant limitation on manuf. firms until 1975. Despite of NEP conditions imposed in 1975 on firms equity, the government relaxed ownership conditions on firms exporting at least 80% of sales. ++ Exchange rates and investment regulations were also made liberal in the 1970s. However, no introduction of innovation rents to stimulate technological upgrading (Schumpeter,1934, 1943). E.g. grants for R&D facilities and HR development of human a la the efforts by Taiwan Hence, export-oriented industrialization in Malaysia in the 1970s was dominated by lowvalue added activities. The only semblance of Keynesian policy use in the 1970s-- the usage of fiscal policies to create employment ++ Heavy integration to the global economy exposed the economy to external shocks, e.g. the price fluctuation of rubber and oil. 5 3. Heavy Industry Promotion— the 1980s Mahathir Mohamad– “Look East Policy” in 1981 to spearhead national-ownership based heavy industrialization; Protection and state ownership targeted at leaving control to Bumiputeras became the call of the government to industrialize. High commodity prices enabled such policy, inclu. Infrastructure across western Malaysia Such Import-substitution policies resembled the type advocated by structural economists failed (example Perwaja & Proton) 1. lacked the introduction of Schumpeterian-type innovation rents that Amsden (1989) had argued were critical in South Korea’s catch up; 2. lacked the use of discipline (stick) required for rents (carrot) to be translated into performance (Chakravaty, 1986). 6 3. Heavy Industry Promotion —the 1980s (cont.) Hence, export-oriented manufacturing industries did not experience strong growth in value added Exception: 1. some inward-oriented manufacturing industries became successful from second round import-substitution. Domestic rents helped offer the scale for learning in klinker and cement production (e.g. YTL ) and highway construction (e.g. UEM); 2. palm oil processing and oleo-chemicals industry grew because of natural resource endowments, government support through crude oil palm export tariffs, R&D rents and price stabilization policies 7 3. Heavy Industry Promotion--the 1980s (cont.) By the mid-1980s commodity prices had crashed to make debt service difficult as the balance of payment deficit began to soar. Its impact was Malaysia facing a recession for the first time as GDP contracted in 1985-86; Unlike S. Korea imposing export quota, neo-liberal policies a la the type Bhagwati (1975), Friedman (1986), Krueger (1980) promoted were quickly back to dominate the Malaysian economy e.g. (renewed tax break incentives to FDI and devalued the ringgit in 1986); Consequence: sales rents from taxes and tariffs continued to buffer the heavy industries, their relative costs soared as the fallen ringgit made payments for imported capital equipment and licensing fees extremely expensive; The lack of effective human capital development policies and pressure to upgrade left these firms to remain dependent on foreign technology. 8 4. Return to Export Orientation- the late 80s to 90s Export incentives were reintroduced to attract FDI 1. Export refinancing schemes 2. Double deduction tax exemptions Massive Capital Inflow 1. foreign-led manuf. sector grew strongly 2. Percentage share FDI in domestic investment rise from 10% in 1980-90 to 25% in 199195 Export surges in 1. Electronics (S’gp and M’sia –biggest production platform) 2. Textile & Garment 3. Resource-based e.g. palm oil processing & wood product 4. Manufacturing driven by growing demand generated by export sector but also enjoyed by inward oriented firms e.g. car, steal & cement 9 4. Return to Export Orientation- the late 80s to 90s Massive expansion of export oriented industries in low value added activities, 1. Labour shortages began to mount as labour-saving technical change was slow. 2. Semi-skilled foreign labour inflows began to grow strongly 10 5. The Asian Financial Crisis Between 1991 till July 2 1997 exchange rates began to appreciate strongly despite growing current account deficits Appreciating ringgit aggravated balance of payments (Figure 2) Eclectic industrial policy saw little technological upgrading to support higher ringgit. Foreign low skilled labour inflows drove competitiveness in low value added manufacturing activities with technological downgrading in the electronics industry Meso-organizations launched since 1991 became white elephants because of ethnic colouring. Economy further liberalized from 1995 as financial institutions embraced market-oriented measures. The contagion from the collapse of the Baht destabilized the ringgit, which became easy not just because of regional integration but more because of vulnerability from growing BOP deficits. Although NPLs and debt soared much of it were domestically denominated, and hence, Malaysian still had 60% international reserves after taking account of current account deficit and short-term debt service. 11 6. Capital controls Government imposed capital controls on September 2 1998 after recognizing that the loss of confidence and runs by speculators would deplete international reserves further Ringgit was fixed MYR3.8 to a USD, ringgit trading abroad was banned, foreign accounts by Malaysians can only be held upon approval by Bank Negara. Ringgit notes of MYR500 and MYR1000 were terminated Declaration and approval of ringgit sent abroad beyond MYR10,000 made mandatory NPLs were sharply reduced following the formation of Capita Fund and Asset Fund which acquired and restructured all NPLs entities Banks were merged to strengthen their financial capacities Interest rates were lowered, and the CGS was used to substitute for collateral requirements. Banks were forced to raise their portfolio of lending to approved national firms enjoying CGS support from Central Bank Current account began recording massive surpluses Foreign portfolio equity investment and FDI declined over the period 1997-2000 Booming US economy helped as along with the other OECD countries it boosted exports. 7. Re-liberalization 12 Following Badawi’s appointment of Prime Minister, the government kept to its stance of liberalizing and democratizing the economy. Capital controls were abandoned and the focus on SMEs increased. Large High tech firms, including foreign firms were also approved grants upfront. The groundwork for the new stance was the New Economic Model prepared with the leadership of liberal economists. While on the one hand, the NEM recommended a great departure away from ethnic-based affirmative action, and called for a focus on human capital development policies, it also called for further liberalization The lack of emphasis on selective interventions to drive technological upgrading drove the economy further to a transition to low value added export manufacturing activities. This has led to electronics and clothing firms increasingly their reliance on cheap little skilled foreign workers. Firms, both national and foreign prefer this arrangement because Malaysia offers far better security and infrastructure than workers’ home countries. The 2007-08 global financial crisis caused a huge collapse in exports, which led a GDP conracting in 2008-09. The consequences include rising household and public debt, overheating in key economic conurbations 13 8. Conclusions While it cannot be denied that Malaysia is generally a success story of rapid economic growth and poverty alleviation among the developing countries, it has to be also said that its eclectic exposure to external markets and mis-interventions has denied the country the regulatory control to shield from disruptive external economic shocks and to promote technological upgrading to become a developed country. On the one hand, there is strong push to liberalize the economy when the interests do not directly collide with the interests of the elites despite recognition that the capital system produces disruptive shocks from time to time. On the other hand, interventions are targeted at consolidating the interests of the political elites, which often generate unproductive outcomes. The nature of politics in the country, which is truncatedly driven by ethnic polarization and dominated by the Bumiputeras has been unproductive. This is the disruptive nature of evolution that is led by collusion rather than collaboration. Under such circumstances, the minority productive species among both majority and minority ethic groups are overwhelmed by a coalition of majority unproductive groups in such groups. Figure 1: Balance of Payments/GDP and Consumer Price Index, Malaysia, 1960-2014 (%) 14 200000 120 180000 100 140000 80 120000 100000 60 80000 60000 40 40000 20000 20 0 -20000 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 Year BOP CPI 2000 2010 0 2020 Consumer Price Index (%) Balance of Payments/GDP (%) 160000 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Percent (%) 15 Figure 2: GFCF, GDP/Capita, Net FDI Inflow/GDP and PEI/GDP, Malaysia, 1960-2014 (%) 40 30 20 10 0 -10 -20 -30 -40 -50 Year Change in GFCF Change in GDP/Capita Net FDI/GDP PEI/GDP 16