The Internationalization process of the Italian Companies: An explorative study to identify the characteristics to succeed in an Eastern-Europe country

advertisement

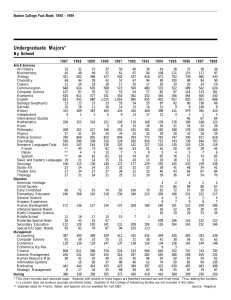

9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 THE INTERNATIONALIZATION PROCESS OF THE ITALIAN COMPANIES: An explorative study to identify the characteristics to succeed in an Eastern-Europe country[1] Andrea Manzoni Cristina Bettinelli Ph.D. candidate post-doctoral research fellow at the Entrepreneurial Laboratory University of Bergamo University of Bergamo Via dei Caniana, 2 – 24127 Bergamo Via dei Caniana, 2 – 24127 Bergamo +39 035 2052691 – +39 035 2052549 +39 035 2052670 – +39 035 2052549 andrea.manzoni@unibg.it cristina.bettinelli@unibg.it Giovanna Dossena Alberto Marino Full professor of Management Full professor of Marketing University of Bergamo University of Bergamo Via dei Caniana, 2 – 24127 Bergamo Via dei Caniana, 2 – 24127 Bergamo +39 035 2052670 – +39 035 2052549 +39 035 2052509 – +39 035 2052549 giovanna.dossena@unibg.it alberto.marino@unibg.it October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 1 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 ABSTRACT Crossing the national border in order to explore a new market can lead the company to enhance its position and to take advantage of the difference (i.e. the gap) between its present market/country and the prospective one. Obviously the intrinsic characteristics of a specific company (e.g. dimension, core business, production and finance capacity, management) and its vocation to the internationalization exert influence both on international strategy and on the modes of entry. Several research has analyzed the firm’ increasing in performance only after the company installed in the foreign country, meanwhile nobody cares if there were similar characteristics that could explain the willingness ex ante of a company to internationalize. The underlying theoretical structure of this explorative analysis concerning the structural characteristics draws on psychological theories on goal-oriented behavior. In other words, decisions regarding companies are seen as the result of management decision making processes and are influenced by companies "attitudes". By company attitudes the authors mean all those companies' traits (e.g. legal form, assets, equity) that characterize their structures. The objective of the present paper is the identification of the potential similarities among the Italian companies in their domestic markets; splitting them up by country of destination. The research confirms that companies operating in certain markets have similar characteristics. This could mean that the decision makers (i.e. leaders/management/entrepreneurs)’ personal vision shapes the company organizational structure (e.g. structural/financial/patrimonial characteristics) and, in turn, it might arrange the suitable entry mode strategy. Keywords: perceived gaps, structural characteristics, Eastern/Southern-East European countries. October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 2 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 1. NTERNATIONAL BUSINESS THEORIES AND NEW POTENTIAL MARKETS Several studies have shown that internationalization lead companies to better performance and growth. The reason for internationalization relies on the: i) gap of technology and innovation between two countries (Vernon, 1966), ii) the possibility to avoid transaction costs (Williamson, 1975), iii) the benefits in performance linked to act in different markets at the same time (Dunning, 1988; 1995). From a theoretical point of view, the origin of the theory on internationalization of firms and the topic of international business is to ascribe to Hymer (1960). He identified that the foreign direct investments were not a simple international flow of capital, but a complex and organized set of transactions that let company transfer not only capital but also technology, knowledge, etc… Today, in the current competitive market, like never before, the businesses have to face to a new scenario that compels them to make a real important choice: Cross the national border looking for a new potential markets; Try to survive in its own market. According to the authors, the only way to go over the present financial and economic crisis is to choose the first option. Crossing the national border in order to explore a new market can lead the company to enhance its position and to take advantage of the difference (i.e. the gap) between its present market/country and the prospective one; according to the most influential international business theories. It seems worthwhile to the authors to specify that the term “gap” or “difference” is used with reference to the cultural, technological, supply and demand (and other factors) gap. October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 3 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 The above mentioned kind of gaps (Beckerman, 1956) oblige companies to choose a specific entry mode strategy instead of another one. As the entry mode is concerned, Busija et al. (1997) state the existence of a relationship between strategy type and modes of entry in a specific country/market (i.e. internal development, acquisition or a mixed mode). Obviously the intrinsic characteristics of a specific company (e.g. dimension, core business, production and finance capacity, management) and its vocation to the internationalization exert influence both on international strategy and on the modes of entry. The literature on this topic, although consistent, is not homogeneous. For instance, Driscoll and Paliwoda (1997) found that socio-cultural distance, tacit know-how and product differentiation influence the foreign market entry mode meanwhile Madhok (1997) identified in the resource-based view, the explanation of the entry mode choice. As the reader can see, the choice of entry mode is a complex one. This is why the authors started a research project aimed at studying the differences and analogies between the companies’ own market/country and the foreign one with reference to: the culture; the technology development; the market openness and its potential; the quality and the pricing of factor of production; and the strategy adopted to “conquer” that market/country. The aforementioned independent variables could be used to understand which factors must be considered to define the most profitable strategy to “hook” a foreign market. The entry mode strategy established by a company can be influenced, above all, by the perceived gaps between their country/market and the country/market of destination. The terminological difference between “gap” and “perceived gap” is that the latest embeds something not material but psychological: the leaders/management/entrepreneurs’ personal October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 4 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics vision. According to the authors, ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 the afore-mentioned vision might influence not only international strategy and the mode of entry in a specific country, but also the domestic business strategy and the domestic company structure as well. Muzychenko (2008) digs deeper in the analysis of the drivers that influence the international strategy. She studied the impact of cultural values in the chance of identify business opportunity. In order to confirm or confute if the same vision leads to the same decision (invest in a specific country) in the same manner (entry mode), it is necessary to analyze the domestic structural characteristics of those companies that invest abroad; splitting them up by country of destination. With the aim to identify the presence of shared structural characteristics among the Italian companies operative in Eastern and Southeastern Europe, an earliest step of the abovementioned research is required. The underlying theoretical structure of this explorative analysis draws on psychological theories on goal-oriented behavior, specifically the Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975) and its extension, Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1988, 1991; Ajzen & Madden, 1986). The central premise of these theories is that behavioral decisions are not made spontaneously but are the result of a reasoned cognitive process in which the behavior is influenced by attitudes. Therefore, before analyzing the entry mode strategy in a specific country, a research upon the characteristics (i.e. attitudes) among the companies that invest in a specific country should be worthwhile. Following the call for business-management-research that incorporates more-realistic visions of human behavior (Beinhocker, Davis, & Mendonca, 2009) we applied these theories to business – strategy - decision-making. In other words, decisions regarding companies can be seen as the result of management decision making processes and are influenced by companies’ "attitudes". By company attitudes we mean all those companies' traits (e.g. legal form, assets, equity) that characterize their structures. October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 5 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 The decision makers’ (i.e. leaders/management/entrepreneurs) visions affect the company’s strategy and characteristics. If this research confirms that companies operating in the same foreign geographic area or nation have similar characteristics, then it could be more likely that those companies are lead by decision makers that have applied similar visions and similar internationalization strategies. 2. ONCEPTUAL ARGUMENTS AND HYPOTHESIS Recent studies on the degree of internationalization and firm performance (Contractor, 2007; Kumar & Singh, 2008), and on the effects of international strategy on modes of entry (Pehrsson, 2008; Rasheed, 2005) state the continued interest of scholars in the area of international business research. However, most research has investigated the link between internationalization and firm performance; taking the firm willingness – in crossing the national border looking for a new potential markets – for grant. Several research has analyzed the firm’ increasing in performance only after the company installed in the foreign country (Caves, 1996; Thomas & Eden, 2004; Pangarkar, 2008; Zeng, Xie, & Wan; 2009); meanwhile nobody cares if there were similar characteristics that could explain the willingness ex ante of a company to internationalize. Due to the lack of empirical research concerning the domestic performance and structural characteristics among the companies before extending abroad their market share, the objective of the present paper, as previously mentioned, is the identification of the potential similarities among the Italian companies in their domestic markets; splitting them up by country of destination: October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 6 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 H1: Italian companies operating in UKRAINE have similar structural characteristics; H2: Italian companies operating in ROMANIA have similar structural characteristics; H3: Italian companies operating in BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA have similar structural characteristics; H4: Italian companies operating in SLOVENIA have similar structural characteristics; H5: Italian companies operating in POLAND have similar structural characteristics; H6: Italian companies operating in EASTERN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES (EECs) have characteristics that are different from those of Italian companies operating in SOUTHERN EASTERN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES (SEECs). Managers, researchers and financial analysts usually use the term business performance to evaluate the business achievement of a company; but the term is rather vague (Yang, 2007) and prior research has used a broad range of performance measures and balance sheet ratio such as sales growth, profit margin, ROA, ROS, ROE, EBIT and so on. Given the absence of a set of universally – accepted indicators of the financial/patrimonial/economic state of companies, this research, based on a review of the available literature and the best practice used by managers, uses the following 11 primary variables: 1. Legal form; 2. Revenues; 3. Assets; 4. Number of employees; 5. EBITDA (Earnings before interests, taxes, depreciation and amortization); 6. Net assets (equity); 7. Net liabilities; 8. ROA (return on assets); 9. ROE (return on equity); 10. Bank / Sales; 11. Debt / Equity October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 7 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 3. ETHODOLOGY 3.1 Sample selection In order to identify the Eastern European and Southern East European countries we considered the United Nations Statistics Division (UNSD) classification. This definition includes all the states which were once under the Soviet Union’s influence and were part of the Warsaw Pact. According to the UNSD definition, Eastern Europe consists of the following ten countries[2]: Belarus, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Moldova, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Ukraine. We consider as part of Southern-East Europe Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro, Serbia, Slovenia and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. From the list of Countries that belong to these two areas we identified a sub-set of countries with the following rule: Italy is in the top 3 ranking of the most relevant economic partners of the country; The country has published a list of the 40 most important Italian companies operating in its territory. Our source of data for the application of this rule was the Italian Institute for Foreign Trade (ICE), also known as Italian Trade Commission. The ICE is the government agency entrusted with promoting trade, business opportunities and industrial co-operation between Italian and foreign companies. The Italian companies willing to operate abroad (either towards importexport activities or outward direct investments) refer to the ICE for receiving support on the spot. Moreover, the ICE can provide information and assistance to all those foreign companies that wish to develop business with their Italian counterpart. October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 8 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 The Italian Institute for Foreign Trade has indeed a network of 117 offices in 87 countries around the world and publishes official reports on foreign countries and on Italian foreign trade. The application of the abovementioned selection rule produced a list of companies with sufficient data for testing our hypothesis. From Eastern Europe the selected countries are: Poland, Romania and Ukraine, from the Southern East Europe the countries of which we have data are Bosnia and Herzegovina and Slovenia. From the data source AIDA we gathered the balance sheets of the Italian companies operating in these countries and created a database. 3.2 Descriptive Statistics Our database is composed of 158 observations. The number of Italian companies divided by foreign country varies slightly because we excluded those with missing values in their balance sheets (see table 1). Table 1: Number of Italian companies operating in Eastern and Southern-Eastern Europe Number of companies UKRAINE 30 ROMANIA 34 POLAND 39 BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA 31 SLOVENIA 24 SOUTHERN EASTERN EUROPE 55 EASTERN EUROPE 103 Total number of companies 158 October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 9 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 The majority of analyzed companies are headquartered in the northern part of Italy and are joint stock corporations (s.p.a.). The described companies are in general medium or large sized. On average they are owned by a group of nine shareholders and are governed by a group of five directors. From table 3 it clearly emerges that Italian companies that operate in the Eastern European area are larger than those operating in the Southern-Eastern area. Interestingly 44% of the former are large and very large while only 16% of the latter are large. It is important to consider that the balance sheets ratios and the structural characteristics such as EBITDA, ROA, ROE, BANK/DEBT revenues might be sector-related. Table 2: Descriptive Statistics: structural characteristics of Italian companies operating in Eastern and Southern-Eastern Europe. N Mean Maximum Company location in Italy =north 158 =south 127 31 Legal form Limited liability 158 52 company (s.r.l.) Joint stock company (s.p.a.) 106 Revenues (€) 158 1,842,463,000 87,256,000,000 Assets (€) 158 2,095,190,000 101,460,000,000 Number of employees 140 3,425 74,717 EBITDA (€) 158 304,502,000 26,104,000,000 EBITDA/Sales 158 8.76 45.54 EQUITY (€) 158 620,070,000 42,867,000,000 October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 10 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 ROA 158 5.69 32.76 ROE 155 9.18 94.66 BankDebt/Revenues 148 22.89 93.00 Number of shareholders 95 9.72 120 Board Size 85 5.80 16 Debt/Equity 151 1.91 22 Table 3: Company Size of Italian companies that operate in Eastern Europe East SouthEast MISSING % 9.7% 14.5% SMALL % 30.1% 41.8% MEDIUM % 15.5% 27.3% LARGE % 27.2% 16.4% VERY LARGE % 17.5% .0% 100.0% 100.0% TOTAL Table 4: Sectors of Italian companies that operate in Eastern Europe October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK East South-East COMMERCE 15.50% 29.10% MANUFACTURING 53.40% 47.30% SERVICES 29.10% 23.60% MISSING 2.00% 0.00% TOTAL 100.00 % 100.00% 11 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 The highest number of businesses are involved in manufacturing in both cases. From our database it emerges that Italian companies that operate in Bosnia and Slovenia with a commercial activity are twice the percentage of those that operate in Eastern Europe in the same sector. Italian companies operating in Eastern Europe are more involved in the services sector than those operating in South-East. 3.3 Methods and Results The formulated hypothesis concern the relationship between a dichotomous variable (operating or not in a specific area) and all the variables that describe the structural characteristics of each Italian company. The latter group of variables are in lager part interval/ratio ones. Taking into consideration the typology of our hypothesis and that this is an exploratory study we will analyze two variables at a time to uncover whether or not they are related. The method which is needed here is the calculation of the Speraman’s rho (Bryman & Bell, 2007). Table 5 indicates the Spearman correlation coefficients and the level of statistical significance. It is important to bear in mind that the results we are going to present uncover relationships among variables but we can’t infer that one variable causes the other. Our aim is indeed to explore and describe the main characteristics of companies operating abroad and not to infer conclusions and predict the companies behaviors. October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 12 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 Table 5: Spearman’s rho, the relationship between the decision to operate in a country and the company’s characteristics UKRAINE ROMANIA BOSNIA & HERZEGOVI NA .142 -.301(**) .264(**) .041 -.120 -.252(**) .076 .000 .001 .606 .134 .001 158 158 158 158 158 158 -.055 .383(**) -.323(**) -.050 .023 .306(**) Sig. (2-tailed) .492 .000 .000 .535 .771 .000 N 158 158 158 158 158 158 -.073 .388(**) -.333(**) -.053 .047 .317(**) .364 158 .000 158 .000 158 .510 158 .559 158 .000 158 Correlation Coefficient SLOVENIA POLAND EAST / SOUTHEAST LEGALFORM Sig. (2-tailed) N Correlation Coefficient REVENUES ASSETS Correlation Coefficient Sig. (2-tailed) N NUMBER OF EMPLOYEES EBITDA NET ASSETS (EQUITY) Correlation Coefficient -.138 .395(**) -.274(**) -.048 .032 .262(**) Sig. (2-tailed) .105 .000 .001 .573 .703 .002 N 140 140 140 140 140 140 Correlation Coefficient -.064 .360(**) -.314(**) -.010 .013 .270(**) Sig. (2-tailed) N .428 158 .000 158 .000 158 .898 158 .874 158 .001 158 Correlation Coefficient -.065 .406(**) -.301(**) -.033 -.023 .276(**) Sig. (2-tailed) .420 .000 .000 .677 .774 .000 N 158 158 158 158 158 158 Correlation Coefficient -.057 .102 -.125 .026 .042 .081 Sig. (2-tailed) .488 .211 .126 .752 .608 .321 N 151 151 151 151 151 151 Correlation Coefficient .006 .092 -.036 .023 -.079 .013 Sig. (2-tailed) .944 .250 .655 .774 .324 .876 N 158 158 158 158 158 158 Correlation Coefficient .026 .182(*) -.091 -.021 -.100 .092 Sig. (2-tailed) .746 .023 .261 .798 .218 .257 N 155 155 155 155 155 155 Correlation Coefficient .033 -.199(*) .040 .158 -.006 -.154 NET LIABILITIES ROA ROE BANK/SALES October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 13 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics Debt/Equity ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 Sig. (2-tailed) N .688 148 .015 148 .634 148 .055 148 .939 148 .062 148 Correlation Coefficient -.015 -.102 .050 .109 -.024 -.125 Sig. (2-tailed) N .853 151 .213 151 .544 151 .181 151 .766 151 .127 151 ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). Table 5 shows that none of the Italian companies characteristics analyzed are related to the decision to operate neither in Ucraina nor in Slovenia nor in Poland. Companies that operate in Romania tend to be more complex (higher revenues, assets value, number of employees, equity and EBITDA). For these companies, the decision of operating in Romania is positively correlated to having a large organizational structure (Rho are +.3 or higher and significance is high). On the other hand, operating in Bosnia is negatively correlated to organizational structure and size indicators. We aggregated the countries by considering the area to which they belong (Southern Eastern Europe VS Eastern Europe). The results show that in general the decision to operate in Eastern Europe is positively correlated with a set of structural and size variables while the decision to operate in Southern Europe is negatively correlated to the same set of variables. Table 6 summarizes our results and shows that in part our hypothesis have been accepted. Confirmed Hypothesis 1 (Ukraine) Refused X Hypothesis 2 (Romania) X Hypothesis 3 (Bosnia and X October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 14 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 Herzegovina) Hypothesis 4 (Slovenia) X Hypothesis 5 (Poland) X Hypothesis 6 (Eastern X /Southern-east) Table 6: Hypothesis confirmation 4. ISCUSSION, LIMITS AND FURTHER RESEARCH As the variable LEGALFORM is concerned, the reason why the limited liability company (s.r.l.) is significant in Bosnia & Herzegovina, meanwhile the joint stock company (s.p.a.) is the most appropriate legal form for the Italian companies that are operating in Romania, relies both on the companies’ sectors and on their sizes. Romania in particular and Eastern European country in general, are indeed characterized by a stronger presence of Italian manufacturing industry (53% in EEc vs. 47% in SEEc). The same trend is confirmed for the size as well; the 44,7% of the Italian companies that invest in an Eastern European country are very big; against the 16,4% of those that operate in a Southern East European country. According to the Italian standard and entrepreneurial mentality, the preferable legal form of both manufacturing industry and big size companies is the joint stock company. With a specific reference to Romania and Bosnia & Herzegovina (countries where the significant variables assume an opposite result), it is worthwhile for the authors to stress that, not by accident, the two countries are characterized by important differences in religious, cultural and living standards spheres. October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 15 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 The positive and the negative signs of the variables reflect the perceived differences by Italian leaders/management/entrepreneurs and the distance[3], not only geographical from those countries and Italy (Beckerman,1956). These differences derive also from the fact that Romania is a member of several economic and political networks (e.g. ONU, WTO, NATO, FAO, GATT, UNESCO, UNICEF). The results of the present explorative analysis, confirm the research hypotheses of our broader project – mentioned at the beginning of this article – about the importance and the influence of the decision makers’ personal visions . The sharing knowledge about a country means that the leaders/management/entrepreneurs’ personal vision will be the same across the companies, and it is the vision that shapes the company (e.g. structural/financial/patrimonial characteristics) towards both its local market and the foreigner one and, in turn, arranges the suitable entry mode strategy. The main limit of these considerations is the uncertainty of business decision makers’ knowledge with regard to a specific country. This is why the authors, are carrying out a survey about the knowledge (e.g. form of government; membership of EU, religion, currency, location, etc…) of the Italian people on Eastern and Southern-East European Countries. However, further research should explore what are the differences and the similarities among these two groups of countries and what are the factors that affect such decisions. October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 16 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 References: Ajzen, I. (1988). Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Milton Keynes, UK: Open University Press. Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, (50): 179–211. Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Ajzen, L., & Madden, T.J. (1986). Prediction of goal-directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 22: 453-474; Beckerman, W. (1956). Distance and the Pattern of Inter-European Trade. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 38(1): 31-40; Beinhocker, E., Davis, I., & Mendonca, L. (2009). The 10 Trends You Have to Watch. Harvard Business Review, 87(7/8): 55-60; Bryman, A., &Bell, E. (2007). Business Research Methods (2nd eds.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; Busija, E.C., O’Neill, & Zeithaml, C.P. (1997). Diversification Strategy, Entry Mode, And Performance: Evidence Of Choice And Constraints. Strategic Management Journal, 18(4): 321-327; Caves, R. (1996). Multinational enterprise and economic analysis (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; Contractor, F.J. (2007). Is International Business Good for Companies? The Evolutionary or Multi-Stage Theory of Internationalization vs. the Transaction Cost Perspective. October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 17 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 Management International Review (MIR), 47(3): 453-475; Driscoll, A.M., & Paliwoda, S. J. (1997). Dimensionalizing International Market Entry Mode Choice. Journal of Marketing Management, 13(1-3): 57-87; Dunning, J.H. (1988). The eclectic paradigm of international production: a restatement and some possible extensions. Journal of International Business Studies, 19(1): 1-31; Dunning, J.H. (1995). Reappraising the eclectic paradigm in the age of alliance capitalism. Journal of International Business Studies, 26(3): 461-491; Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Believe, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Hymer, S.H. (1960). The international operation of national firms: a study of direct investment. Ph.D. dissertation, M.I.T. Published by M.I.T. Press in 1976; Kumar, V., & Singh, N. (2008). Internationalization and performance of Indian pharmaceutical firms. Thunderbird International Business Review, 50(5): 321-330; Muzychenko, O. (2008). Cross-cultural entrepreneurial competence in identifying international business opportunities. European Management Journal 26: 366– 377; Madhok, A. (1997). Cost, Value And Foreign Market Entry Mode: The Transaction And The Firm. Strategic Management Journal, 18(1): 39-61; Pangarkar, N. (2008). Internationalization and performance of small- and medium-sized enterprises. Journal of World Business, 43(4): 475-485; Pehrsson, A. (2008). Strategy antecedents of modes of entry into foreign markets. Journal of Business Research, 61(2): 132-140; October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 18 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 Rasheed, H.S.(2005) Foreign Entry Mode and Performance: The Moderating Effects of Environment. Journal of Small Business Management, 43(1): 41-54; Thomas, D.E., & Eden, L. (2004). What is the Shape of the Multinationality-Performance Relationship? Multinational Business Review, 12(1): 89-110 Vernon, R. (1966). International investment and International trade in the product cycle. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 80: 190-207; Williamson, O.E. (1975). Market and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust implications. New York, NY: Free Press; Yang, H. (2007). The effect of financial independence on the performance of life companies. International Journal of Management, 24(3): 522-540; Zahra, S., Korri, J. S. & Yu, J. (2005) Cognition and international entrepreneurship: Implications for research on international opportunity recognition and exploitation. International Business Review 14: 129–146; Zeng, S., Xie, X.M., &Wan, T.W. (2009). Relationships between business factors and performance in internationalization An empirical study in China. Management Decision, 47(2): 308-329. October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 19 9th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-2-7 Footnotes: [1] Even if this paper is the result of the shared research of both the authors, the § n. 1 can be attributed to Andrea Manzoni; the § n. 3.3 can be attributed to Cristina Bettinelli; the § n. 3.1 can be attributed to Giovanna Dossena; the § n. 2 can be attributed to Alberto Marino. The § n. 3.2 can be attributed to both Giovanna Dossena and Cristina Bettinelli and the § n. 4 can be attributed to both Andrea Manzoni and Alberto Marino. [2] United Nations Statistics Division- Standard Country and Area Codes Classifications (M49) http://unstats.un.org/unsd/methods/m49/m49regin.htm#europe [accessed on the 1st of Aug 2009] see also the World Population Prospects Population Database http://esa.un.org/unpp/definition.html [accessed on the 1st of Aug 2009]; [3] The term “distance” involves the cultural values and the entrepreneurial environment between Italy and the foreign country as well as the characteristics and the behavior of the decision makers. It is acknowledged and accepted by the academic literature, and demonstrated by several studies, that cognitive processes and behaviors are shaped by the interaction between the entrepreneur and their environment (Zahra et al., 2005). October 16-17, 2009 Cambridge University, UK 20