Monitoring Models Of Firms Growth: A Discriminant Analysis Of The Djia

advertisement

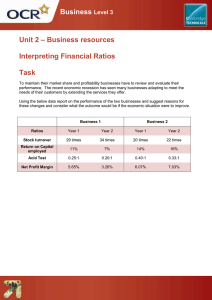

8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 Monitoring Models of Firms’ Growth: A Discriminant Analysis of the DJIA Dr. Tarek Ibrahim Eldomiaty* Associate Professor of Finance Misr International University Faculty of Business Administration Finance Department PO Box 1 - Heliopolis 11341 Cairo EGYPT (Tel: +02 (2) 4477 1560) (Fax: +02 (2) 4477 1566) E-mail: tarek_eldomiaty@hotmail.com Sahar Charara University of Dubai Finance & Banking Department College of Business Administration PO Box: 14143 Dubai United Arab Emirates (Tel: +9714-2072718) (Fax: +9714-2242670) E-mail: sahar_charara@hotmail.com May 2008 * Corresponding Author October 18-19th, 2008 Florence, Italy 1 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 Monitoring Models of Firms’ Growth: A Discriminant Analysis of the DJIA Abstract This paper examines three possible explanations of firm’s growth: (1) a firm grows according to its sales growth, (2) a firm grows according to saving costs, and (3) a firm grows according to the two factors being used simultaneously; that is increasing sales by saving costs. The paper uses corporate quarterly data from the DJIA30 covering the period 1990-2006. The paper introduces a new measure of firm growth based on sales-weighted fixed assets growth. The methodology utilizes the properties of the discriminant analysis to build three Z-Score models each of which discriminates low-growth firms from high-growth firms. The first model discriminates between low-growth and high-growth firms based on sales ratios. The second model discriminates between low-growth and high-growth firms based on cost ratios. The third model discriminates between low-growth and highgrowth firms based on both sales and cost ratios. According to the properties of the discriminant models, the discriminant power of the model is a determinant of the power of the model’s information content. The results show that the three discriminant models have relatively the same discriminant power (60%). This means that the revenue and cost factors are used simultaneously as drivers of firm growth. Nevertheless, the information content in the third model (which examines the simultaneous use of sales and cost factors) reveals high relative dependence on sales ratios than cost ratios. This result provides support to the practice of the growth-size theory of firm growth. The results have practical implications to corporate managers regarding the sales and cost factors that are to be considered to promote firm growth. JEL classification: M21 Key words: Theory of Firm Growth, Discriminant Analysis, Z-Score Models, DJIA index October 18-19th, 2008 Florence, Italy 2 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 I. Introduction The theory of firm growth has always been considered a critical factor in the evolution of the business literature (mainly economics, finance, marketing and accounting). The literature has been characterized by a diversity of the factors affecting firm’s growth and the lack of consensus on these factors. This diversity has resulted in two competing theories trying to explain the factors that determine firm’s growth; the growth-size theory and growth-learning theory. The former focuses on the trend of the revenue curve as a measure of firm’s growth, while the latter focuses on the trend of the cost curve as a proxy for the progress of the learning process and firm’s growth. Since the two theories go in opposite directions, there has not been a consensus on what theory explains the practice of firm’s growth. The former is concerned with the relationship between firm’s growth and its size (using sales revenue, employees and assets as proxies). The latter is concerned with the behavior of the cost function as a result of firm’s learning process. The main concern of this paper is that it is possible that the two relationships contradict each other which may not provide a complete picture on how firms grow. That is, firms may try to increase sales revenues, number of employees or the assets’ size which result in increases in costs. In this case, the growth-learning relationship may not provide a possible explanation on how firms grow. If the firm is trying to minimize costs, it is also possible that sales revenue, number of employees and assets would be affected negatively. That is why the authors are trying to explore a new approach to examine firm’s growth which is to examine the proportionate weight of the October 18-19th, 2008 Florence, Italy 3 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 sales revenue and costs to firm’s growth. In this case the discriminant analysis provides much help. The approach of this paper is to examine the drivers of firms’ growth based on the use of sales information and cost information. The former takes into account the relationship between sales and the other items in the firm’s income statement and balance sheet. The latter takes into account the relationship between cost of goods sold and the other items in the firm’s income statement and balance sheet. The sales ratios are used as a proxy for examining the growth-size relationship since the authors introduce a new measure of firms’ growth based on ‘sales-weighted fixed assets growth.’ The cost ratios are used as a proxy for examining the growth-learning relationship. The paper is organized as follows. Section II reviews the relevant literature on the models of firm growth. Section III outlines the research objectives. Section IV outlines the research hypothesis. Section V describes the data and research variables examined in the study. Section VI describes the structure of the discriminant analysis employed in this paper. Section VII shows the results. Section VIII discusses the results. Section IX concludes. II. Models of Firm Growth: A Review of the Relevant Literature The literature on firm’s growth is very rich and has been subject to intensive debate for decades. That debate has resulted in the evolution of the literature of industrial organization. The underlying concern in the literature is how firms grow. Many significant efforts have presented possible explanations (or theories). This paper does not attempt to provide a review to the literature since it is voluminous; rather the paper focuses on two basic relationships upon which firms’ growth has been examined October 18-19th, 2008 Florence, Italy 4 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 independently, namely; the growth-size relationships and growth-learning relationships. What follows is a review of the relevant studies that examined each relationship independently. 1. Growth-Size Relationships These relationships are considered the oldest to explain firm’s growth. Robert Gibrat (1931) presented the first explanation of growth with applications to inequality of income distribution, concentration of enterprises and populations of cities. Since then, the literature evolved upon extended applications to the economics of firm’s growth based on Gibrat’s proportional growth law. It assumes that firm’s growth rate is independent of both its current size and its past growth history. Kalecki, (1945), Hart & Prais (1956) Hart (1962) and Clarke (1979) presented a validation to Gibrat’s law. Simon and Bonini (1958) found that Gibrat’s law holds for firms associated with above the minimum efficient size level. Mansfield (1962) describes the growth-size independence as “the probability of a given proportionate change in size during a specified period being the same for all firms in a given industry regardless of their size at the beginning of the period. Although Gibrat’s growth-size independence was examined in many studies using static specifications, Ijiri and Simon (1964) reached the same conclusion using dynamic specifications. Lucas (1967) and Lucas and Prescott (1971) found that firm’s capital adjustment, employment and output follow Gibrat’s law. In an extended distinguished effort, Lucas (1978) used Gibrat’s law to prove the existence of equilibrium in both developed and developing economies. It is worth noting that the previous theories apply to the complete size distribution. Nevertheless, Scherer (1980) considered the small-size firms and reported a negative October 18-19th, 2008 Florence, Italy 5 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 relationship between firm’s size and growth. Nelson and Winter (1982) report a concave relationship which implies that firm growth increases with firm size, then decreases with firm size. The contradiction to Gibrat’s law has also been presented by Geroski (1995), Sutton (1997) and Caves (1998). An extended strand to the literature reported a negative relationship between firm growth and size (Evans, 1987; Hall 1987; Dunne et al., 1989; Mata, 1994; Dunne and Hughes, 1994; Audretsch, 1995; Hart and Oulton, 1996; Weiss, 1998; Audretsch et al., 1999; Almus and Nerlinger, 2000; Bechetti and Trovato, 2002; Goddard et al., 2002). Chen and Lu (2003) add another element to the literature by examining the Taiwanese service sector in addition to the usual manufacturing sector. They found that Gibrat’s law does not hold for the latter sector but does for the former. It is quite obvious that taking firm’s size into consideration results in some contradicting results. That is, a positive growth-size relationship exists in the large firms while a negative relationship does exist in the small firms. Sutton (1997) supports this conclusion pointing out that these contradictory results lies in systematic differences in the samples selected. The earlier studies included only large firms, while more recent studies included small firms. In the present study, the authors examine the determinants of growth apart from size. The reason is two fold. First, the authors believe that the firms’ growth matters relatively more than size because any firm considers drivers of growth as first priority rather than changing its size. The decision to change size occurs after the growth rate has been determined. Second, the conclusions regarding firm’s growth-size are not deterministic since firm’s size October 18-19th, 2008 Florence, Italy 6 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 changes over time. This is the main reason that the authors examine firm’s growth from a different angle which is to classify firms according to growth rates. 2. Growth-Learning Relationships The cost elements have also been examined in the literature on firm’s growth. The early beginning was in Jacob Viner’s paper (1932) about the size distribution of firms. Viner introduced the theory that a unique size of a firm exists within an industry under the assumption that firms have a U-shaped long run average cost functions which assume that each firm produces at the minimum point of this curve. Overall, in equilibrium, the industry allocates production over firms so as to minimize total costs. A criticism has been introduced to this theory on the ground that when firms sells in a large product markets, costs would increase due to an increasing demand. Nevertheless, Lucas (1967) presented a modified version of Viner’s theory based on a ‘constant-returns-to-scale’ that assumes that firms produce at minimum resources cost.1 The literature has considered another element of firm’s growth which is learning. It has been observed that innovation helps firms grow fast. It is also well known that innovation requires extra costs to incur. That is, firm’s growth can be explained by observing the cost functions. Jovanovic (1982) and Lippman and Rumelt (1982) conclude that firms’ efficiency can be observed through the behavior of the cost functions. The latter have been studied based on the convexity assumption which holds for cost functions such as linear-quadratic and Cobb-Douglas. In this regard, 1 Robert Lucas (1978) extended his analysis to the aggregate levels to support his claim that producing at minimum resources cost does exist. His aggregate theory implies that policies to modernize backward economies by consolidation and policies to resist conglomerates in advanced economies may both be misguided. October 18-19th, 2008 7 Florence, Italy 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 Jovanovic (1982) developed a model that assumes that output is a decreasing convex function of managerial inefficiency. Actually, this is true since inefficiency implies increasing costs to scale. III. Research Objectives The paper aims at examining the objectives that follow. 1. Examine the type and weights of the sales information that discriminates between low-growth and high-growth levels. 2. Examine the type and weights of the cost information that discriminates between low-growth and high-growth levels. 3. Examine the type and weights of the sales and cost information that discriminates between low-growth and high-growth levels. IV. Research Hypothesis This paper aims at examining the hypotheses that follow. H1: A negative relationship exists between firm’s growth and cost-based ratios. H2: A positive relationship exists between firms’ growth and sales revenue-based ratios. H3: A positive relationship exists between firms’ growth and both of cost-based and sales revenue-based ratios. The 3rd hypothesis is based on certain marketing considerations. That is, when firms are expecting or actually facing high demand, the production volume increases which requires increases in production costs. V. Data and Research Variables Data October 18-19th, 2008 Florence, Italy 8 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 The data used in this study is obtained from Reuters® for the non-financial firms included in the DJIA30 index. The data cover the years 1989-2006 on quarterly basis. The basic forms of the data are the income statement and balance sheets. The sales ratios and cost ratios are calculated by the authors. Dependent Variables The dependent variable is firm’s growth which can be measured as: FA t Sales t Firm Growth Ln FA t -1 Max Sales The advantage of this measure is that it takes into account the growth of sales and fixed assets simultaneously. The methodology examines two levels of firms’ growth: lowgrowth (1st quartile) and high-growth (3rd quartile). Independent Variables The independent variables are the cost ratios and sales ratios. The methodology examines also the combined effect of the both types of ratios at a time. Discriminant, Content and Construct Validity The effectiveness of the discriminant analysis and the resulted discriminant models requires a test for discriminant validity, content and construct validity (Podsakoff, and Organ, 1986). In this case, the classifications and use of sales ratios and cost ratios provide quite distinctive dimensionality. This means that the issue of discriminant validity is well settled. Regarding the issues of content and construct validity, the sales ratios and cost ratios are drawn from relevant literature that adequately provides a multidimensional perspectives. In addition, these ratios are considered an adequate coverage of October 18-19th, 2008 Florence, Italy 9 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 the important content, therefore, provide a good basis for content validity (Nunnally, 1978). Since the variables have been empirically examined in many related studies in the literature of firm growth, they provide an adequate evidence of construct validity. VI. Method The discriminant analysis is the most common technique used to develop a Zscore model. The problem that is addressed with discriminant analysis is how well it is possible to separate two or more groups of observations (i.e., individuals, companies …etc.), given measurements for these observations on several variables (Manly, 1998; Hair, et al., 1995). Therefore, the discriminant analysis is a statistical technique used to classify an observation into one of several a periori groupings dependent upon the observation’s individual characteristics. It is used primarily to classify and/or make predictions in problems where the dependent variable appears in qualitative form, e.g., high or low risk stocks, bankrupt or non-bankrupt …etc. In general, the qualitative form is to be classified into two different groups. In the field of business, the discriminant analysis has been initially utilized by Altman, (1968, 1971), Altman and Sametz, (1977) and Altman and Fleur, (1981) by building a Z-Score model to discriminate between bankrupt and non-bankrupt firms using public accounting information. There are a lot of Z models that are used in the discriminant analysis. Most of these models are derived for the evaluation of company solvency. In the literature of finance, interests in this model, and the methodology itself, have continued in the work of Wilcox (1971), Edmister (1972), Deakin (1972), Blum (1974), Sinkey (1975), Taffler (1978, 1982, 1983, 1984) and Sudarsanam (1981). Discriminant Function Analysis October 18-19th, 2008 Florence, Italy 10 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 It is sometimes useful to be able to determine functions of the variables X 1 , X 2 , …,X p that in some sense separate the m groups as well as is possible. The simplest approach involves taking a linear combination of the X variables Z = a 1 X 1 + a 2 X 2 +…+a p X p For this purpose, in such a way that Z reflects group differences as much as possible. Groups can be well separated using Z if the mean value changes considerably from group to group, with the values within a group being fairly constant. One way to choose the discriminant coefficients a 1 , a 2 ,…, a p in the index is therefore so as to maximize the F ratio for a one-way analysis of variance. Hence a suitable function for separating the groups can be defined as the linear combination for which the F ratio is as large as possible. When this approach is used, it turns out that it may be possible to determine several linear combinations for separating groups. In general, the number available is the smaller of p and m-1. This is one of the advantages of the linear discriminant analysis. That is, the reduction of the analysis space dimensionality, i.e., from the number of different independent variables X to m-1 dimension (s). As this paper is concerned with only two groups, consisting of below-median and above-median risk (systematic and unsystematic), the resulted Z function is only one function (i.e., onedimension analysis). When the discriminant coefficients are applied to the actual ratio, a basis for classification into one of the mutually exclusive groupings exists. In this regard, the discriminant analysis technique has the advantage of considering an entire profile of characteristics common to the relevant observations (i.e., companies) as well as the interaction of these characteristics. The linear discriminant analysis has also the October 18-19th, 2008 Florence, Italy 11 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 advantage of yielding a model with a relatively small number of selected measurements, which has the potential of conveying a great deal of information (Altman, 1968, 1971; Altman and Sametz, 1977). VII. Results and Discussion The Z-Score Models According to the methodology, three linear discriminating functions with their Z index (Z model) are derived. This procedure is designed to develop a set of discriminating functions which can help predict grouping companies in the DJIA30 index based on the values of sales and cost ratios. The two groups considered are the lowgrowth firms and high-growth firms. Using a stepwise selection algorithm, certain variables are determined significant predictors of grouping. The algorithm was carried out three times: for cost ratios, sales ratios and both of cost and sales ratios all together at a time. The discriminating functions with p-value 0.05 are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level. Table (1) shows the discriminating functions with its standardized coefficients for cost, sales and cost & sales ratios. October 18-19th, 2008 Florence, Italy 12 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 Table 1: The Components of the Discriminant Models for Firms’ Low-Growth and HighGrowth Levels Components of the Z models Equation Coefficients2 Cost Ratios COGS/Preference Dividends 0.564 COGS / Current Assets -0.488 COGS / Total Liability -1.334 COGS / Current Liability 1.310 3 Eigenvalue 0.063 % of Variance 100% Canonical Correlation 0.243 Wilks-Lambda 0.941 2 55.43* x n 917 Sales Ratios Preference Dividend Turnover -0.51 Current Assets Turnover 0.573 Total Liability Turnover 1.356 Current Liability Turnover -1.269 Eigenvalue 0.071 % of Variance 100% Canonical Correlation 0.258 Wilks-Lambda 0.934 2 62.81* x n 917 Cost & Sales Ratios COGS / Fixed Assets 0.68 COGS / Current Liabilities 1.331 Preference Dividend Turnover 0.43 Current Assets Turnover -0.33 Total Assets Turnover -1.149 Total Liability Turnover -0.951 Eigenvalue 0.089 % of Variance 100% Canonical Correlation 0.286 Wilks-Lambda 0.918 2 78.04* x n 917 * Significant at 1% significance level. 2 3 Standardized Canonical Discriminant Function Coefficients. The variance in a set of variables explained by a factor or component, and denoted by lambda. An eigenvalue is the sum of squared values in the column of a factor matrix, or factor loading for variable i on factor k, and m is the number of variables. October 18-19th, 2008 13 Florence, Italy where aik is the 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 Table (1) reports the significant coefficients of cost ratios and sales ratios that discriminate between low-growth and high-growth firms. With regard to cost information, the ratios of cost of goods sold (COGS) to current assets and total liability have negative coefficient. This indicates a negative relationship between firms’ costs and growth. Nevertheless, the coefficient of COGS/current liability is positive which indicates that long-term debt affects firms’ growth negatively. This is to imply that capital structure matters when planning for firm’s growth. With regard to sales information, firms’ liabilities present an implication analogous to cost ratios. That is, the negative coefficient of current liabilities turnover and the positive coefficient of total liabilities turnover imply that sales are affected by long term debt positively. This also indicates that capital structure matters when planning for sales growth. The positive coefficient of current assets turnover indicates that sales growth is affected by current rather than fixed assets. The negative coefficient of preference dividend turnover is expected since preference dividends are constant, thus not associated with the increases in sales revenues. When both of cost ratios and sales ratios are examined all together at a time, extended implications can be reached. The negative coefficients of current assets and fixed assets turnover indicate that firms’ growth is negatively associated with assets. This implies that Gibrat’s law does not hold for large size firms as much as it does not for small firms as mentioned above in the literature review. The positive coefficient of COGS/fixed assets indicates that firms’ growth is positively affected by both types of costs which carries the same implication as the results of the cost ratios do. The positive coefficient of preference dividend turnover contradicts the negative coefficient reported October 18-19th, 2008 Florence, Italy 14 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 in the sales ratios which could be due to data discrepancies. Nevertheless, the authors believe that the negative coefficient is more realistic according to the nature of preference dividends. Since the two groups are in equal size, the model can be used operationally. 4 The estimated prior probability ratios were used to calculate the cut-off points on the Z-Scale as shown in tables 2 and 3. The cut-off points are calculated as Ln(P1/P2), where P1= the prior probability of low-growth level and P2= the prior probability of high-growth level. Table 2: The Cut-Off points for the Cost, Sales and Cost-Sales Discriminant Models Prior Probability Cut-Off Points Low High Growth Growth Cost Ratios, Sales ratios, and Cost & -0.004 5 Sales ratios 49.9% 50.1% Relative Contribution of the Model’s Discriminatory Power The usefulness of the discriminant analysis requires that the final variables profile is to show the relative contribution of each variable to the total discriminating power of the Z-Score model and the interaction between them as well. The common approach used to assess the relative contribution is based on measuring the proportion of the Mahalanobis D 2 -distance between the centriods of the two constituent groups accounted for by each variable (Mosteller and Wallace, 1963; Taffler, 1981, 1983).6 4 The prior probability ratio is an estimate of the proportion of companies with a ratios’ profile more similar to that of group 1 and group 2. 5 Since the two groups are in equal size, the cut-off point is the same for the three types of ratios. r jf r js cj 6 P j = 2 c r i 1 r 4 if and i r is if Where P j = The proportion of the D -distance accounted for by ratio j r is = The means of the below-median and above-median groups for ratio i respectively. October 18-19th, 2008 Florence, Italy 15 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 Table 3: Relative Contribution of the Models’ Discriminatory Power Components of the Z model Cost Ratios COGS/Preference Dividends COGS / Current Assets COGS / Total Liability COGS / Current Liability Sales Ratios Preference Dividend Turnover Current Assets Turnover Total Liability Turnover Current Liability Turnover Cost & Sales Ratios COGS / Fixed Assets Relative Contribution * 15.26% 13.20% 36.09% 35.44% 13.75% 15.45% 36.57% 34.22% 13.96% 27.32% COGS / Current Liabilities Preference Dividend Turnover 8.83% 6.77% 23.59% 19.52% Current Assets Turnover Total Assets Turnover Total Liability Turnover * Mosteller-Wallace measure. Table 3 shows that: 1. With regard to the cost ratios, the ratios of Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) to firms’ total and current liabilities contribute the most to model discriminatory power (36.09% and 35.44% respectively). This outcome shows that when firms are to adjust costs, firms’ liabilities are to be considered. 2. With regard to the sales ratios, firms’ total and current liabilities turnover ratios contribute the most to the model discriminatory power (36.57% and 34.22% respectively). This outcome carries the same implications that the cost ratios do. That is, when firms are to adjust sales, firms’ liabilities are to be considered. It is October 18-19th, 2008 Florence, Italy 16 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 worth noting that firms’ liabilities are common factors in both cost and sales ratios which carry the implication that firms’ growth is quite interrelated by the capital structure. 3. When the cost and sales ratios are examined all together at a time, a new perspective is presented by two ratios which are associated with the highest relative contribution to the model discriminatory power. The first is the ratio of COGS/Current liabilities (27.32%) and the second is the total assets turnover (23.59%). The first ratio carries the implication above mentioned that firms’ growth is affected by the capital structure. The second ratio carries the implication that firm’s growth is also affected by its size (in terms of total assets). It is also worth noting that in table 1, the coefficient of total asset turnover is negative and statistically significant which does not provide support to Gibrat’s law in the case of large size firms. The Accuracy-Matrix of the Z model: In the multi-group case, a measure of success of the discriminant analysis is to be addressed. This measure results in a classification table or “Accuracy-Matrix,” as shown in figure 1 (Altman, 1968). Actual Group Membership Predicted Group Membership Below Median Above Median Below Median H M1 Above Median H M2 Figure (1) The Accuracy-Matrix of the discriminant analysis The actual group membership is equivalent to the priori groupings and the model attempts to classify correctly these companies. At this stage, the model is basically explanatory. When new companies are classified, the nature of the model is predictive. October 18-19th, 2008 Florence, Italy 17 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 The H’s (Hits) stand for correct classifications and the M’s (Misses) stand for misclassification. M 1 represents a Type I error and M 2 represents a Type II error. The jack-knife test, or Lachenbruch Holdout Test, (Lachenbruch, 1967) is the readily statistical test for producing the classification table. The final results of the jack-knife test are shown in Table IV. Therefore, Type I and Type II can be easily observed according to the “Accuracy-Matrix” shown in figure 1. It is worth noting that tables (5) and (6) show that Type I errors are all less than type II errors in both cases of systematic and unsystematic risk. This is considered a support to the relatively high reliability of the estimated discriminant models. Table 4: Lachenbruch Holdout Test (jack-knife test), Low-High Growth Firms Actual Group No. of cases Predicted Group Membership Membership Cost Ratios7 Low Growth High Growth Low Growth 458 263 195 57.4% 42.6% High Growth 459 164 295 35.7% 64.3% Sales Ratios8 Low Growth High Growth Low Growth 458 271 187 59.2% 40.8% High Growth 459 180 279 39.2% 60.8% Cost & Sales Ratios9 Low Growth High Growth Low Growth 458 275 183 60% 40% High Growth 459 183 276 39.9% 60.1% 7 Percent of "grouped" cases correctly classified: 60.9%. Percent of "grouped" cases correctly classified: 60%. 9 Percent of "grouped" cases correctly classified: 60.1%. October 18-19th, 2008 18 Florence, Italy 8 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 Table 4 shows that the three discriminant models have relatively the same discriminant power (60%). This means that the revenue and cost factors are used simultaneously as drivers of firm growth. Nevertheless, table 3 shows very important implication (which is also an advantage to the use of discriminant analysis for examining firm’s growth) that sales ratios’ contribution (58.72%) is relatively higher than cost ratios’ contribution (41.28%). This result shows that firms’ growth depends much relatively on the combined effect of sales’ and assets’ growth. VIII. Conclusion This study examines the relationship between firms’ growth, sales information and cost information. The study utilizes the benefits of the discriminant analysis to build up quantitative models that discriminate between low-growth and high-growth firms. The results indicate that firms’ growth is affected by cost elements and sales elements although the latter is relatively more contributable to firm’s growth than the former. The results also indicate that firm’s growth is negatively associated with assets growth which implies that Gibrat’s law does not hold for large-size firms. This is true since the sample include the firms in the DJIA30 index. The results also indicate that growth is also affected by firm’s capital structure. The results carry implications to corporate managers that firm’s growth can be achieved by initiating more sales and less cost. October 18-19th, 2008 Florence, Italy 19 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 REFERENCES Almus, M. and Nerlinger, E. 2000. Testing Gibrat’s law for young firms: Empirical results for West Germany. Small Business Economics, 15(1): 1-12. Altman, Edward I. 1968. Financial Ratios, Discriminant Analysis and the Prediction of Corporate Bankruptcy. Journal of Finance, 23(4): 589-609 ______________. 1971. Corporate Bankruptcy in America. Lexington, Mass.: D. C. Heath. Altman, E. I., Jacquillat, B. and Levasseur, M. 1974. Comparative Analysis of Risk Measures: France and the United States. Journal of Finance, 29: 1495-1511. ______________. & Arnold W. Sametz, editor. 1977. Financial Crises: Institutions and Markets in a Fragile Environment, John Wiley & Sons Inc. Altman, E. I. & J. K. La Fleur. 1981. Managing a Return to Financial Health. The Journal of Business Strategy, 2(1): 31-38. Audretsch, D. 1995. Innovation and Industry Evolution. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Audretsch, David B., Santarelli, E. and Vivarelli, M., 1999. Start-up size and industrial dynamics: Some evidence from Italian manufacturing. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 17(7): 965-983. Bechetti, L. and Trovato, G. 2002. The determinants of growth for small and medium size firms. Small Business Economics, 19(4): 291-306. Blum, M. 1974. Failing Company Discriminant Analysis. Journal of Accounting Research, 12(1): 1-25. Caves, R. 1998. Industrial organization and new findings on the turnover and mobility of firms. Journal of Economic Literature, 36(4): 1947-1982. Chen, J. and Lu,W. 2003. Panel unit root tests of firm size and its growth. Applied Economics Letters, 10(6): 343-345. Clarke, R. 1979. On the lognormality of firm and plant size distributions: some U.K. evidence. Applied Economics, 11(4): 415-433. Deakin, Edward B. 1972. A Discriminant Analysis of Predictors of Failure. Journal of Accounting Research, 10(1): 167-179. October 18-19th, 2008 Florence, Italy 20 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 Dunne, T., Roberts, Mark J. and Samuelson, L., 1989. The growth and failure of US manufacturing plants. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 104(4): 671-698. Dunne, P. and Hughes, A. 1994. Age, size, growth and survival: UK companies in the late 1980s. Journal of Industrial Economics, 42(2): 115-140. Edmister, Robert O. 1972. An Empirical Test of Financial Ratio Analysis for Small Business Failure Prediction. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 7(2): 1477-1493. Evans, David S. 1987. Tests of alternative theories of firm growth. Journal of Political Economy, 95(4): 657-674. Geroski, P. 1995. What do we know about entry? International Journal of Industrial Organization, 13(4): 421-440. Gibrat, R. 1931. Les inégalités économiques; applications: aux inégalités des richesses, a la concentration des entreprises, aux populations des villes, aux statistiques des familles, etc., d’une loi nouvelle, la loi de l’effet proportionnel. Paris: Librairie du Recueil Sirey. Goddard, J., Wilson, J., and Blandon, P. 2002. Panel tests of Gibrat’s law for Japanese manufacturing. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 20(3): 415-433. Hall, B. 1987. The relationship between firm size and firm growth in the US manufacturing sector. Journal of Industrial Economics, 35(4): 583-606. Hair, J. F., R. E. Anderson, R. L. Tatham & W. C. Black. (1995), Multivariate Data Analysis. 4th Edition, Macmillan, New York. Hart, P. E. and Prais, S. J. 1956. The Analysis of Business Concentration: A Statistical Approach. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A (General), 119(2): 150-191. Hart, P. E. 1962. Size and growth of firms. Economica, 29(1): 29-39. Hart, P. E. and Oulton, N. 1996. The size and growth of firms. Economic Journal, 106(438): 1242-1252. Ijiri, Y. and Simon, H. A. 1964. Business firm growth and size. American Economic Review, 54(2): 77-89. Jovanovic, B. 1982. Selection and evolution of industry. Econometrica, 50: 649-670. Kalecki, M. 1945. On the Gibrat Distribution. Econometrica, 13(2): 161-170. October 18-19th, 2008 Florence, Italy 21 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 Lachenbruch, P. A. 1967. An Almost Unbiased Method of Obtaining Confidence Intervals for the Probability of Misclassification in Discriminant Analysis. Biometrics, 23(4): 639-645. Lippman, Steven A. and Rumelt, R. P. 1982. Uncertain imitability: An analysis of interfirm differences in efficiency under competition. Bell Journal of Economics, 13: 418-438. Lucas, Robert E., JR. 1967. Adjustment Costs and the Theory of Supply. Journal of Political Economy, 75(4, part 1): 321-334. Lucas, Robert E., JR. and Prescott, Edward C. 1971. Investment under Uncertainty. Econometrica, 39(5): 659-681. Lucas, Robert E. JR., 1978. On the Size Distribution of Business Firms. The Bell Journal of Economics, 9(2): 508-523. Manly, Bryan F. J. 1998. Multivariate Statistical Methods: A Primer. Chapman & Hall, 2nd Edition, London. Mansfield, E. 1962. Entry, Gibrat’s law, innovation, and the growth of firms. American Economics Review, 52(5): 1023-1051. Mata, J. 1994. Firm growth during infancy. Small Business Economics, 6(1): 27-39. Mosteller, F. & D. L. Wallace. (1963) “Inference in the authorship problem”, Journal of the American Statistical Association, 58(302): 275-309. Nelson, Richard R. and Winter, Sidney G. 1982. An evolutionary theory of economic change. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press Nunnally, Jum C. 1978. Psychometric Theory. 2nd Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York. Scherer, Frederic M. 1980. Industrial Market Structure and Economic Performance. 2nd edition, Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Sinkey, JR. Joseph F. 1975. A Multivariate Statistical Analysis of the Characteristics of Problem Banks, Journal of Finance, 30(1): 21-36. Simon, Herbert A. and Charles P. Bonini. 1958. The Size Distribution of Business Firms. The American Economic Review, 48(4): 607-617. Sutton, J. 1997. Gibrat’s legacy. Journal of Economic Literature, 35(1): 40-59. October 18-19th, 2008 Florence, Italy 22 8th Global Conference on Business & Economics ISBN : 978-0-9742114-5-9 Taffler, R. J. 1978. The Assessment of Financial Viability using Published Accounting Information and a Multivariate Approach. Association of University Teachers of Accounting Review, 10(1): 53-68. _________. 1981. The Assessment of Financial Viability and the Measurement of Company Performance. Working Paper No 27, City University Business School, London. _________. 1982. Forecasting Company Failure in the UK using Discriminant Analysis and Financial Ratio Data. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A 145(Part 3): 342-358. _________. 1983. The Assessment of Company Solvency and Performance Using a Statistical Model. Accounting and Business Research, 13(52): 295-307. _________. 1984. Empirical Models for the Monitoring of UK Corporations. Journal of Banking and Finance, 8(2): 199-227. Viner, J. 1932. Cost curves and supply curves. Zeitschrift Für Nationalökonomie, 3: 2346. Weiss, C. 1998. Size, growth and survival in the upper Austrian farm sector. Small Business Economics, 10(4): 305-312. Wilcox, Jarrod W. 1971. A Simple Theory of Financial Ratios as Predictors of Failure. Journal of Accounting Research, 9(2): 389-395. October 18-19th, 2008 Florence, Italy 23