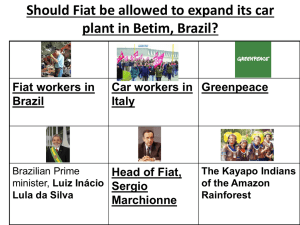

An Organizational Adaptation Approach To Firm's Crisis: Evidence From Fiat 1990 - 2007

advertisement