2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Influences of Organizational Vision on Organizational Effectiveness

Doris W. Carver, Ph.D.

Vice President, Continuing Education

Piedmont Community College

United States of America

(336) 322-2111

carverd2010@gmail.com

I’d like to acknowledge my support team; my family, Bob, Barbie, Ross, Justin, and Nicole; and

friends and colleagues, who offered words of encouragement, prayers, and advice. Special

thanks to Dr. Shawn Carraher, Dr. John Parnell, Dr. Stephen Fitzgerald, Angel Solomon, Ernest

Avery, and Stacey Wood.

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

1

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Influences of Organizational Vision on Organizational Effectiveness

ABSTRACT:

This quantitative study explored the relationship between organizational vision and

organizational effectiveness from an organizational theory perspective. The purpose of this

study was to increase the base of knowledge on organizational theory pertaining to strategic

management by conducting an empirical study showing the relationship between organizational

vision and organizational effectiveness while moderating for organizational size and age.

Organizational vision was operationalized using the seven vision attributes (e.g. brevity, clarity,

abstractness, challenge, future orientation, stability, and desirability) developed by Baum, Locke,

and Kirkpatrick (1998). Organizational effectiveness was operationalized using financial and

non-financial measures (e.g. three financial measures of return on investments (ROI), return on

assets (ROA), and change in sales (chgsales); and the three non-financial measures of

organizational goals, profitability satisfaction, and industry growth). This study expected to find

that organizations that had organizational visions would have higher degrees of organizational

effectiveness than organizations that did not have organizational visions. It further expected to

find that institutions with processes that utilized institution wide input from participants of all

levels in the organization would be more effective organizations than those that had only one

person’s (usually the Chief Executive Officer (CEO)) or the board of director’s/trustee’s (BOD)

input into the process of developing organizational vision. The findings indicated mixed results.

INTRODUCTION:

This quantitative study explored the relationship between organizational vision and

organizational effectiveness from a strategic management view of organizational theory.

Creating a vision had been cited by many organizational theorists as being important to the

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

2

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

success of an organization (Baum, Locke, & Kirkpatrick, 1998; Baum, Locke, & Smith, 2001;

Baum & Locke, 2004; Collins & Porras, 1994; Daniels, 2004; Larwood, Falbe, Kriger, &

Miesing, 1995; Lipton, 2004; Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1983).

The purpose of researching organizational vision and organizational effectiveness was to

determine the processes organizations had for developing positive relationships between these

two constructs and what influenced excellence in these areas. Since organizational vision was

seen as a starting point of a transformational process, it was important to understand this

relationship (Collins & Porras, 1994: Kotter, 1990; Sashkin, 1988). It was also important to note

that while leadership traits of organizational leaders impact organizations, both successfully

(Kouzes & Posner, 1987) and negatively (Hayward, Shepherd, & Griffin, 2006; Lipton, 2004),

the focus of this study did not analyze the impact of leadership on organizational vision or on

organizational performance.

Organizational effectiveness was the ultimate purpose of organizations, and therein lays

its significance to organizational theory (Cameron, 1986(a); Cameron, 1986(b)). Organizations

that are not effective, eventually ceased to exist. The purposes for this study were to determine

the relationship between organizational vision and organizational effectiveness, with moderating

effects for organizational size and age, and to determine the correlation between the seven

dimensions of organizational vision (i.e. the vision attributes of brevity, clarity, abstractness,

challenge, future orientation, stability, and desirability) and organizational effectiveness (Baum,

et al., 1998; House & Shamir, 1993). This study also examined organizations that reported no

organizational vision and the comparison of the organizational effectiveness of these two groups:

organizations with organizational vision and organizations without organizational vision. For the

purpose of this research, only explicit visions were considered as being organizational visions.

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

3

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Explicit visions were those visions that were clearly stated and defined. Unspoken or tacit

visions were not considered, because 1) it was very difficult to capture this data and 2) tacit

vision appeared to be more appropriate to examine within an organization instead of across

organizations. Finally, this study examined any correlations between organizational vision,

organizational effectiveness, and the mediating variable named “whoinput”. The “whoinput”

variable consisted of three levels. These three levels were: 1) high (institution wide input into

developing organizational vision), 2) medium (the development of organizational vision by

TMTs), and 3) low (organizational vision that was developed by CEOs and/or BODs).

Organizational effectiveness was cited as the ultimate dependent variable in empirical research

on organizations (Cameron, 1986(a); Cameron, 1986(b)). If evidence supported the theory that

organizational vision leads to organizational effectiveness, then businesses would have a key tool

for improving the process for designing successful organizations.

SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STUDY:

The significance of this quantitative study was to enhance and expand the knowledge

base on organizational theory by identifying which dimensions of organizational vision most

influenced organizational effectiveness, and by determining what impact organizational size,

age, and participant input had on organizational vision and ultimately organizational

effectiveness. Empirical research showed that organizational vision was important to

organizational effectiveness in both small and large, simple and complex organizations (Baum, et

al., 1998; Filion, 1991; Kotter, 1990; Westley & Mintzberg, 1989). Many of the studies

reviewed used primarily qualitative methods for studying organizational vision and

organizational effectiveness (Collins & Porras, 1991; Westley & Mintzberg, 1989). Kantabutra

(2006) related vision-based leadership to sustainable business performance using vision

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

4

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

attributes designed by Baum, et al. (1998), and he recommended that for future research it would

be important to “know which of the seven vision attributes” was the most critical to the vision

components (p. 48).

By identifying the organizational vision variables that influence organizational

effectiveness, this study sought to define the variables that have the most significant influence on

organizational effectiveness. By studying the relationship that organizational vision had to

organizational effectiveness and the impact of who has input into the process of developing

organizational vision, a new perspective could be studied that would add new knowledge to

organizational theory.

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE:

A literature review on the topic of organizational vision yielded many studies on

organizational vision. The same was true for organizational effectiveness. There were many

studies on the relationship between organizational vision and organizational effectiveness as they

related to leaders/leadership (Baum & Locke, 2004; March & Sutton, 1997; Quigley, 1994;

Snyder & Graves, 1994; Wang, 2002), organizational vision and job performance (Chorpenning,

2000; Wiedower, 2001), and leaders/leadership disconnected from organizational success

(Aldrich and Martinez, 2001). The focus of this research was not on leadership, but on

organizational vision and its impact on organizational effectiveness. There were very few

studies that compared organizational vision to any part of organizational effectiveness

(Kantabutra, 2006; Lipton, 2004). Two studies found closely related organizational vision to any

element of organizational effectiveness, without leadership as a key focus, were the studies by

Baum, et al. (1998; 2001) and Kantabutra (2006).

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

5

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Organizational effectiveness

There were many financial indicators for determining organizational effectiveness. Two

dominate organizational effectiveness measures were rate of return on equity and rate of return

on total assets (Cox, 1977). Other studies found that financial measures of profitability should

have been used to measure organizational effectiveness (Ansoff, 1965; Baum, et al., 1998; Child,

1977; Cox, 1977; Dess, et al., 1995; Hitt, Clifford, Nixon, & Coyne, 1999; Durand, 1999;

Schendel & Hofer, 1979). Ansoff (1965) found that “rate of return on investments is a common

and widely accepted yardstick for measuring business success” and is applicable in different

industries (Ansoff, 1965, p. 53).

The study by Baum, et al. (1998) examined the relationship of organizational vision to

venture capital. In the study of entrepreneurial organizations, they found a significant

relationship between vision attributes and organizational effectiveness as measured by venture

growth. Venture growth, the organizational effectiveness construct, was operationalized using

the measures of sales growth, annual employment growth, and average annual profit growth

(Baum, et al., 1998). Baum, et al. (1998) used organizational level performance and

organizational effectiveness terms interchangeably.

A study by Parnell (2005) focused on the financial measures of sales growth, return on

equity (ROE), return on assets (ROA), and on the non-financial measures of performance

satisfaction and industry vigor. Research indicated that these financial measures were valid

methods for conducting research on organizational effectiveness. This research also indicated

that non-financial measures were valid methods for conducting research on organizational

effectiveness (Parnell, 2005).

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

6

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Research showed that the weakness of using a single-variable (effectiveness) model

could have been overcome by introducing at least two or three effectiveness variables in

empirical models (Hitt, Clifford, Nixon, & Coyne, 1999; Murphy, Trailer, & Hill, 1996).

Research by Judge (1994) indicated that organizational effectiveness was closely linked with

financial performance measures. There were “two general approaches used in the measurement

of effectiveness – those used by business executives and policy researchers and those used by

organizational researchers” (Hitt, 1988, p. 29). The two major financial measurement

approaches were accounting measures and the capital asset pricing model (Hitt, 1988). The

accounting measures included return of investments, return on assets, return on equity, and

earnings per share.

Financial measures

Return on assets was a “valuable indicator of how efficiently management has utilized

the firm’s resources” (Hitt, Clifford, Nixon, & Coyne, 1999, p. 69). Parnell and Carraher (2001)

supported the use of ROA as a measure. In one of Parnell and Carraher’s (2001) studies, they

calculated ROA based on a mean for a two-year period. This study examined ROA for a twoyear period. Return on assets was calculated by dividing average total assets into net income.

Return on investments (ROI) was calculated by dividing the average stockholder’s

equity, or owner’s equity, into net income available to stockholders or net income for owner(s)

(Shim & Siegel, 2000). This ratio indicated the rate of return earned on investments.

Sales growth was measured as the increase in sales from one period of time to the next,

usually expressed in annual sales, divided by annual sales of the base period (i.e. (((gross sales

for 2006 + gross sales for 2007) / 2) / gross sales for 2006) (Baum, Locke, & Kirkpatrick, 1998).

Sales growth was essential to financial planning and budget planning (Droms, 2003).

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

7

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Non-financial measures

Non-financial measures of performance satisfaction and industry vigor were examined.

Scales to measure organizational goals and profitability satisfaction, and industry growth were

developed and validated by Parnell (2000), Parnell and Carraher (2001), and Parnell (2005). The

measures from Parnell’s study (2005) resulted from his research in the strategic management

field while examining “management as an art or science, strategic emphasis on consistency or

flexibility, and strategy as a top-down or bottom-up approach” (Parnell, 2005, p. 2). There were

eight survey statements that addressed the non-financial measures. These statements were 1) I

am satisfied with the current profitability of my company as compared to the competition, 2) I

am satisfied with the current growth of my company as compared to the competition, 3) My

organization is doing a good job of meeting its goals and objectives, 4) My organization’s

current level of financial performance exceeds the industry norm, 5) Our industry growth is

relatively stable, 6) The potential for profit in this industry is relatively strong, 7) The industry is

growing at a fast pace, and 8) The boundaries of the industry in which my company operates are

clear (Parnell, 2005). The alpha for performance satisfaction is .8072 and the alpha for industry

vigor is .6646 (Parnell, 2005). The loading measures for each statement above are statements 1)

.855, 2) .872, 3) .856, 4) .591, 5) .695, 6) .823, 7) .595, and 8) .711 (Parnell, 2005).

For the purpose of this study, organizational effectiveness was operationalized using both

financial and non-financial measures, which included the financial measures of sales growth,

return on investments (ROI), return on assets (ROA), and the non-financial measures of

organizational goals (OG), profitability satisfaction (PS), and industry growth (IG).

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

8

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Organizational vision

Organizational vision was defined as the ideal that represented or reflected the shared

vision to which the organization should have aspired (House & Shamir, 1993). This was the

definition that was used in this research because the literature review revealed that this definition

or very similar definitions were used most often, and it also reflected the researcher’s belief of

organizational vision. Senge (1990) found that shared vision was linked to organizational

effectiveness. Wiedower (2001) examined shared organizational vision as it related to job

performance, organizational commitment, and organizational members’ intent to leave the

organization. Her research supported the importance of having a shared vision that would be

communicated throughout a vision driven organization.

In order for organizational vision to have been effective, action must have been taken

(Nanus, 1992). Strategy was the process by which action was taken. Strategy was the “pattern

or plan that integrates an organization’s major goals, policies, and action sequences into a

cohesive whole” (Seth & Thomas, 1994, pp. 166-167). Mission “describes who the organization

is and what it does…it is a statement of purpose, not direction” (Levin, 2000, p. 93).

Organizational vision and strategy were the catalysts that moved the organization into a future

state (Bennis & Nanus, 1985).

Organizational vision and organizational effectiveness were key components of

organizational theory, and organizational vision serves a critical role in the success of today’s

organizations (Lipton, 1996; 2004). There has been extensive research on the topic of

organizational vision, and this topic included structure and organizational vision (Larwood et. al.,

1995), strategic management and visionary leadership (Baum & Locke, 2004; Westley &

Mintzberg, 1989), vision and venture growth (Baum, et al., 1998; Baum & Locke, 2004),

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

9

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

organizational vision and visionary organizations (Collins & Porras, 1991), vision and leadership

(Bennis & Nanus, 1985; House & Shamir, 1993; Kouzes & Posner, 1987: Peters, 1987; Snyder

& Graves, 1994), and vision and motivation (Daniels, 2004). The literature revealed that there

was no one best definition for organizational vision. There were many definitions of

organizational vision. One definition of this term described organizational vision as a “future

state of the organization” (Bennis & Nanus, 1985, p. 89). For the purpose of this study,

organizational vision was defined as the ideal that represented or reflected the shared vision to

which the organization should aspire (House & Shamir, 1993).

Organizational vision was of vital importance to understanding organizational

effectiveness. The studies by Baum, et al. (1998; 2001) and Kantabutra (2006) used seven vision

attributes to assess organizational vision. The Baum, et al. (1998) organizational vision study

focused on choices that leaders made and actions taken by leaders to guide the organization.

Kantabutra’s (2006) study examined the relationship between organizational vision and

sustainable business effectiveness, using the same seven vision attributes that Baum, et al. (1998)

created (p. 37). For the purpose of this study, organizational vision consisted of constructs that

were made up of many attributes and were labeled as vision attributes. These vision attributes

included brevity, clarity, abstractness, challenge, future orientation, stability, and desirability

(Baum, et al., 1998).

Brevity

Brevity was a key component of forming an effective vision statement (Baum, et al.,

1998). In order for vision statements to have been effective, they must have been brief and

communicated frequently (Locke, et al., 1991). “The ideal vision statement contains 11-22

words” (Kantabutra & Avery, 2003, p. 3). Brevity also did not mean that the briefer a vision

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

10

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

statement, the better it was at creating organizational vision. Vision statements must have been

long enough to encompass the other six vision attribute characteristics and succinct enough to be

communicated effectively (Locke,, et al., 1991; Peters, 1987). The vision must have been clear,

so that everyone within the organization may have been able to understand its meaning. Brevity

and clarity improved the communication of a vision (Kantabutra & Avery, 2003; Kotter, 1990;

Yukl, 1998). A clear vision combatted confusion, clarified purpose, and gave direction (House

& Shamir, 1993; Jacobs & Jaques, 1990; Kouzes & Posner, 1987; Nanus, 1992).

Clarity

A clearly defined vision strengthened and supported organizational functions and added

to the members’ ability to work toward a shared vision (Sashkin & Burke, 1990).

Communicating a clear vision to organizational members, in ways that compelled them to buy

into the vision, creates a shared vision (Sashkin, 1988; Daniels, 2004). A clearly communicated

organizational vision assisted in overcoming resistance to change (Palmer, 2004). Clarity of

vision served to improve the remembrance of goals and the relationship of goals to goal

obtainment (Jacobs & Jaques, 1990; Sashkin, 1988). Clarity also included clarifying the

organization’s direction and working towards achieving the vision (Sashkin, 1988). Nanus

(1992) found that a clear vision combated confusion and clarified organizational purpose and

direction. Senge (1990) found that a clear vision was necessary to motivate individuals and

groups to realize desired results. This study defined clarity as the “degree to which a vision

statement directly points at a prime goal it wants to achieve with a clearly indicated timeframe”

(Kantabutra & Avery, 2003, p. 3).

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

11

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Abstractness

Adding further to the interaction between the vision attributes was the fact that the vision

must have been broad based enough so as not to have been restrictive to the organization as it

changed over time. The vision statement should have been abstract, not abstract in clarity, but

abstract as it related to the representation of a general idea, not a one-time specific goal (Baum,

et al., 1998; Kantabutra, 2006; Locke, et al., 1991). Vision statements should have been abstract

enough to meet long-term goals of the organization and should not have been so narrow as to

have been one-time goal oriented, then easily discarded (Locke, et al., 1991; Nanus, 1992). This

study defined abstractness as the “degree to which a vision statement is not a one-time goal that

can be met and then the vision is discarded” (Kantabutra & Avery, 2003, p. 3).

Future orientation

The vision must have been abstract enough that changes to the organization over time did

not impact the focus of the vision. This is not to say that once a vision was established, it must

never have been changed. Sometimes visions do change, and the organization must establish

new visions. Because it was normal for organizations to change over time, by its very nature,

vision was future oriented. Vision was a desired future state (Collins & Lazier, 1992; Collins &

Possar, 1994; Jacobs & Jaques, 1990). Organizational vision reflected the shared vision to which

the organization should have aspired (Kouzes & Posner, 1987). Visions were future oriented

(Baum, et al., 1998; Collins & Lazier, 1992; Jacobs & Jaques, 1990; Kantabutra, 2006; Kotter,

1990; Lipton, 1996; Locke, et al., 1991; Senge, 1990) and focused on the long-term perspectives

of the organization and the environment in which it functioned (Baum, et al., 1998; Kantabutra,

2006; Locke, et al., 1991). Vision attracted commitment, energized and created meaning for

people, established a standard of excellence, and bridged the present to the future (Nanus, 1992).

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

12

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Vision directed the organization into the future (Kotter, 1990; Sashkin, 1988). This study

defined future orientation of vision as the “degree to which a vision statement indicates the longterm perspective of the organization and the environment in which it functions” (Kantabutra &

Avery, 2003, p. 3).

Challenging

Brevity, clarity, abstractness, and future orientation vision attributes were joined by

desirability and challenging to produce organizational vision. Challenging was another vision

attribute that examined the “degree to which a vision statement motivates members to try their

best to achieve a desirable outcome” (definition used in this study) (Kantabutra & Avery, 2003,

p. 3). Visions challenged people to try to do their best to achieve a desired outcome (Baum, et

al., 1998; Kantabutra, 2006; Locke, et al., 1991). A vision must have motivated members to

work toward the vision’s goal. A vision must have instilled employee confidence (Bennis &

Nanus, 1985). Organizational members had a need for meaningful achievement (Sashkin &

Burke, 1987). Nanus (1992) and Jacobs and Jaques (1990) found that people wanted to commit

to a significant challenge that was worthy of their best efforts, in essence, making a meaningful

difference. Members who shared a vision were challenged to achieve the vision and thereby

strengthened and supported the organization’s functions and direction (Jacobs & Jaques, 1990;

Sashkin, 1988).

Desirability

Desirability was considered the most important criterion of a vision (Locke, et al., 1991).

Followers must have wanted to achieve or work towards obtaining the vision (Baum, et al., 1998;

Kantabutra, 2006; Lipton, 1996; Locke, et al., 1991; Kouzes & Posner, 1987; Sashkin 1988).

Visions should have been designed to provide roles for members, so they had meaningful

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

13

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

responsibility, and they had methods for effectively coordinating and integrating activities based

on involvement, not structure or rules (Sashkin, 1988). Vision helped keep members moving in

the desired direction despite internal and external influences (Kotter, 1990). This study defined

desirability as the “degree to which a vision statement states a goal and how the goal directly

benefits staff” (Kantabutra & Avery, 2003, p. 3).

Desirability and challenging attributes were shown to instill employee commitment

which enhanced organizational effectiveness (Nanus, 1992). Desirability attracted emotional

commitment from organizational members (Kantabutra, 2006; Nanus, 1992). This commitment

helped to lay the foundation for moving the organization forward and for improving

organizational effectiveness. A vision that created a desired future state moved organizational

members from a present state to a future state (Senge, 1990). Vision created direction for the

organizational members (Collins & Lazier, 1992; Collins & Possar, 1994; Jacobs & Jaques,

1990; Kantabutra, 2006; Kotter, 1997; Lipton, 1996; Levin, 2000).

Stability

For vision statements to be useful, they must also have had stability and must not have

changed frequently or been easily influenced by the market or changes in technology (Baum, et

al., 1998; Kantabutra, 2006; Locke, et al., 1991). Changes should only have been “minor

adjustments to reflect changes in the operating environment” (Locke, et al., 1991, p. 52).

“Occasionally, an entirely new vision statement is required, but only if the organization needs to

undergo a significant transformation” (Locke, et al., 1991, p. 52). Stability for this study was

defined as the “degree to which a vision statement is unlikely to be changed by any market or

technology change” (Kantabutra & Avery, 2003, p. 3).

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

14

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

METHODOLOGY:

This research study was a non-experimental study that used survey data. The purpose of

this survey study was to test the theory of organizational behavior that related organizational

vision (e.g. vision attributes) to organizational effectiveness (e.g. financial and non-financial

measures), while accounting for any influence that organizational age and organizational size

may have had on this relationship. The sample population was entrepreneurial organizations in

North Carolina. The independent variable, organizational vision, was operationalized using the

seven vision attributes of brevity, clarity, abstractness, challenge, future orientation, stability, and

desirability (Baum, et al., 1998). The dependent variable, organizational effectiveness, was

operationalized using the three financial measures of return on investments (ROI), return on

assets (ROA), and change in sales (chgsales); and the three non-financial measures of

organizational goals, profitability satisfaction, and industry growth. The unit of analysis for this

study was the organizational level.

Survey instrument

A survey instrument developed by Baum, et al. (1998) and modified by Kantabutra and

Avery (2003) was used in order to further research conducted by Baum, et al. (1998) and

Kantabutra and Avery (2003). Modifications to the instrument for this study only impacted

demographic information.

Statistical methods

This quantitative study explored the relationship between organizational vision and

organizational effectiveness from a strategic management view of organizational theory. The

nature of the sample, data, and data preparation led to multiple applications of generalized linear

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

15

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

analysis. This study presented analysis using organizational size and organizational age as

moderating variables. Whoinput was analyzed as a mediating variable.

The researcher had planned to use multiple regression analysis, but because the data was

not normally distributed (i.e. failed the test of normality), an alternative method of analysis was

used. This study utilized a generalized linear model (GLM) using a gamma distribution model

with a log link.

Model

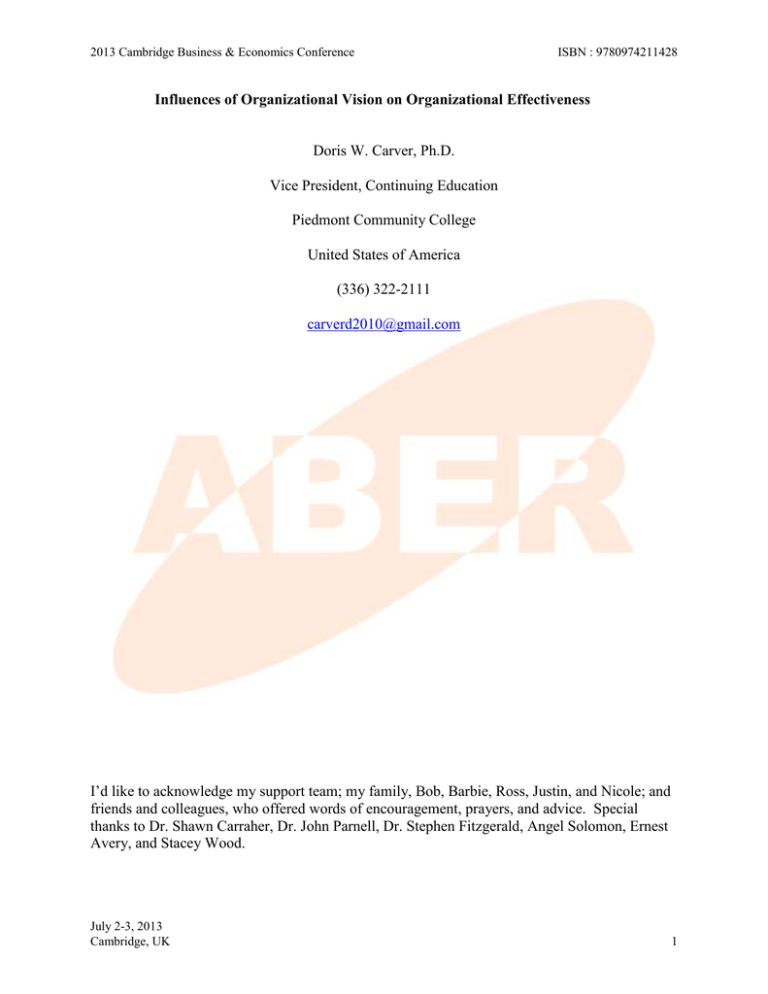

Figure 1 depicts the diagram showing the relationship between organizational vision and

organizational effectiveness while moderating for organizational size and age. The independent

variable was vision attributes. The dependent variable was organizational effectiveness. The

moderating variables were organizational size and age. The mediating variable of who

developed the organizational vision was also included in the model.

RESULTS:

Sample, data collection, and data preparation

Privately held entrepreneurial firms in North Carolina were surveyed in this study, but

only those organizations that had been in operation for three or more years were examined. The

list of entrepreneurial organizations was obtained from InfoUSA, a database marketing service

organization (www.infousa.com). Industry designation was not collected. While participants

from North Carolina entrepreneurial firms were selected, this research model is applicable to

other industries.

A random sampling was generated from the population size of 87,361 North Carolina

entrepreneurial businesses. Eight hundred participants were sent surveys. A total of 163

participants responded, for a response rate of 20.4 percent. This sample size was adequate for

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

16

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

the analysis. The primary statistical method used in this study was generalized linear model

(GLM) using a gamma distribution model with a log link (McCullagh & Neldar, 1989).

Data was captured using a secure website (web-online surveys.com). Once data was

captured from participants, the information was uploaded to an Excel spreadsheet. The Excel

spreadsheet data was then uploaded into SPSS for coding and analysis.

Mean substitution was used in this study to calculate values for missing data. This

method was used because it provided all cases with complete information, which resulted in a

relatively strong relationship among variables and generally yielded consistent results (Hair, et

al., 2006).

Correlation results

The purpose of this non-experimental research study was to determine the relationship

between organizational vision and organizational effectiveness in order to generalize from a

sample to population inferences regarding organizational vision and organizational effectiveness.

Presented in Table 1 (Kendall's tau) are the results for means, standard deviations, and

correlations. This study found, as expected, that there were statistically significant correlations

between the vision attributes of brevity, abstractness, challenging, future orientation, stability,

desire, and the aggregated vision attributes. The correlations between the vision attributes and

the aggregated vision attributes, using Kendall’s tau, were significant at 0.01 (2-tailed).

This study also found that for change in sales (chgsales) and clarity/goal, clarity/time,

abstractness, challenging, future orientation, stability, desirability, and vision attribute; the

correlations were significantly different from zero at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). This indicated that

there was a correlation between organizational vision and organizational effectiveness for the

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

17

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

dependent variable of change in sales. Note that there was not a statistically significant

correlation between change in sales and brevity.

For the correlation between return on investments (ROI) and the variables, there were no

statistically significant correlations. There was a statistically significant positive correlation

between ROI and return on assets (ROA) at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). For the correlations

between ROA and the variables, there were no statistically significant correlations.

The correlation between who had input (whoinput) into defining organizational vision

and the variables indicated that all of the relationships were statistically significant at the 0.01

level (2-tailed). Reporting on the results using Kendall’s tau, the positive correlations between

who had input and brevity, clarity/goal, clarity/time, abstractness, challenging, future orientation,

stability, desirability, and vision attributes were statistically significant.

Financial measures and mediation

For Step 1 of this analysis, this study found that for the financial measures, no

statistically significant relationships were observed for organizational vision (aggregated and

individual attributes) with organizational effectiveness. Steps 2 through 4 were not completed

because there were no statistically significant relationships observed for the IV-DV relationship.

Non-financial measures and mediation

For Step 1 of this analysis, statistically significant relationships were observed for several

of the vision attributes (VA) on two of the non-financial dependent variables: organizational

goals (OG) and profitability satisfaction (PS). Specifically, aggregated vision attributes, brevity,

clarity-goals, clarity-time, abstractness, challenging, future orientation, stability, and desirability

were significantly related to organizational goals, and challenging was significantly related to

profitability satisfaction.

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

18

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

The statistically significant associations observed from Step 1 of the above analysis are

further analyzed in the next steps. Step 2 of the Baron and Kenny analysis also required that the

IV predicts the mediator. For Step 2 of the Baron and Kenny analysis, statistically significant

relationships were observed for the aggregated vision attributes and challenging to whoinput.

Table 2 presents the findings using the Baron and Kenny analysis. This indicates that the only

potential mediating effects of whoinput were for aggregated vision attributes and challenging to

organizational goals, and for challenging to profitability satisfaction. Steps 3 and 4 below show

the final mediating effects of whoinput.

The effects in both Steps 3 and 4 are estimated in the same equation, with Step 4

requiring that the effect of X on Y controlling for M (path c') should be zero. These steps test to

determine if the IV is not statistically significant and if the mediator, whoinput, is statistically

significant. Using Steps 3 and 4 of the Baron and Kenny analysis, the results of this study found

that for the non-financial measures challenging was observed to be significantly related to

organizational goals (Table 3). Additionally, the analysis showed that the relationship of

organizational vision to organizational effectiveness was actually negative.

Hypotheses testing summary

In summary, for the financial measures, this study found that for all of the hypotheses

(Table 4) there were no significant relationships observed; therefore, all of the hypotheses were

not supported. For the non-financial measures, this study found mixed results for the hypotheses

(Table 4). The results of this study also showed that the sign of the coefficients of the significant

results for some of the non-financial indicators for Hypotheses H1a-H1h were negative. Table 4

presents the results for each hypothesis of this study.

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

19

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

CONCLUSION:

This non-experimental quantitative study explored the relationship between

organizational vision and organizational effectiveness from a strategic management view of

organizational theory. The purpose of this study was to determine the relationship between

organizational vision and organizational effectiveness, while accounting for any influence of

organizational age, organizational size, and whoinput. The findings from this study provided

additional understanding of this relationship.

A primary focus of this study was to test the defined research questions and the

hypotheses regarding the influences of organizational vision on organizational effectiveness.

The results of this study found that no statistically significant relationships were observed

between organizational vision and organizational effectiveness for ROI, ROA, and change in

sales. For the non-financial measures, organizational goals and organizational vision all vision

attributes were found to be statistically significant. For the non-financial measure, profitability

satisfaction, the vision attribute, challenging was found to be statistically significant. For

industry growth, the third non-financial measure, no statistical significance was observed.

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

20

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

References

Ansoff, H. I. (1965). Corporate strategy: An analytic approach to business policy for growth

and expansion. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social

psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal

of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173-1182.

Baron, R. A., & Ward, T. B. (2004). Expanding entrepreneurial cognition’s toolbox: Potential

contributions from the field of cognitive science. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice,

Winter Issue, 553-573.

Baum, J. R. (1994). The relation of traits, competencies, vision, motivation, and strategy to

venture growth. Dissertation. (UMI No. 9526175).

Baum, J. R. & Locke, E. A. (2004). The relationship of entrepreneurial traits, skills, and

motivation to subsequent venture growth. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(4), 587-598.

Baum, J. R., Locke, E. A., & Kirkpatrick, S. A. (1998). A longitudinal study of the relation of

vision and vision communication to venture growth in entrepreneurial firms. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 83(1), 43-54.

Baum, J. R., Locke, E. A., & Smith, K. G. (2001). A multidimensional model of venture growth.

Academy of Management Journal, 44(2), 292-303.

Bennis, W., & Nanus, B. (1985). Leaders: The strategies for taking charge. New York: Harper

& Row.

Cameron, K. S. (1986 (a). A study of organizational effectiveness and its predictors.

Management Science, 32(1), 87-112.

Cameron, K. S. (1986 (b). Effectiveness as paradox: Consensus and conflict in conceptions of

organizational effectiveness. Management Science, 32(5), 539-553.

Child, J. (1977). Organizational: A guide to problems and practice. New York: Harper & Row.

Chorpenning, D. (2000). Components in the design and implementation of an organizational

vision. (UMI No. 9959018).

Collins, J. C., & Lazier, W. C. (1992). Beyond entrepreneurship: Turning your business into an

enduring great company. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Collins, J. C., & Porras, J. I. (1991). Organizational vision and visionary organizations.

California Management Review, 34(1), 30-52.

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

21

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Collins, J. C., & Porras, J. I. (1994). Built to last: Successful habits of visionary companies. New

York: HarperCollins.

Cox, W. E., Jr. (1977). Product portfolio strategy, market structures, and performance. In H. B.

Thorelli (Eds.), Strategy + structure = performance: The strategic planning imperative

(pp. 83-102). Bloomington & London: Indiana University Press.

Daniels, J. (2004). Driving to make things happen. Industrial Management, 46(6), 20-25.

Dess, G. G., Gupta, A., Hennart, J., & Hill, C. W. L. (1995). Conducting and integrating strategy

research at the international, corporate, and business levels: Issues and directions. Journal

of Management, 21(3), 357-393.

Droms, W. G. (2003). Finance and accounting for nonfinancial managers. Cambridge, MA:

Perseus Publishers.

Durand, R. (1999). The relative contributions of inimitable, non-transferable and nonsubstitutable resources to profitability and market performance. In M. A. Hitt, P. G.

Clifford, R. D. Nixon, and K. P. Coyne (Eds.), Dynamic strategic resources:

Development, diffusion and integration (pp. 67-95). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons,

LTD.

Filion, L. J. (1991). Vision and relationships: Elements for an entrepreneurial metamodel.

International Small Business Journal, 9, 112-131.

Hair, J. F., Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate

data analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Hayward, M. L. A., Shepherd, D. A., & Griffin, D. (2006). A hubris theory of entrepreneurship.

Management Science, 52(2), 160-172.

Hitt, M. A. (1988). The measuring of organizational effectiveness: Multiple domains and

constituencies. Management International Review, 28(2), 28-40.

Hitt, M. A., Clifford, P. G., Nixon, R. D., & Coyne, K. P. (1999). The development and use of

strategic resources. In M. A. Clifford, P. G. Clifford, R. D. Nixon, & K. P. Coyne (Eds.),

Dynamic strategic resources: Development, diffusion, and integration (pp. 1-14).

Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, LTD.

House, R. J., & Shamir, B. (1993). Toward the integration of transformational, charismatic and

visionary theories of leadership. In M. M. Chemers and R. Ayman (Eds.), Leadership

theory and research: Perspectives and directions (pp. 81-107). San Diego, CA:

Academic Press.

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

22

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Jacobs, T. O., & Jaques, E. (1990). Military executive leadership. In K. E. Clark & M. B. Clark

(Eds.), Measures of leadership (pp. 281-295). West Orange, NJ: Leadership Library of

America, Inc.

Judge, W. Q., Jr. (1994). Correlates of organizational effectiveness: A multilevel analysis of a

multidimensional outcome. Journal of Business Ethics, 13(1), 1-10.

Kantabutra, S. (2006). Relating vision-based leadership to sustainable business performance:

A Thai perspective. Leadership Review, 6(Spring 2006), 37-53.

Kantabutra, S. (2007). Vision effects in customer and staff satisfaction in Thai retail store: An

empirical investigation. Leadership and Organizational Development Journal,

forthcoming.

Kantabutra, S. (2009). Toward a behavioral theory of vision organizational settings. Leadership

and Organizational Development Journal, 30(4), 319-337.

Kantabutra, S. (2010). Vision effects: A critical gap in educational leadership research. The

International Journal of Educational Management, 24(5), 376-402.

Kantabutra, S., & Avery, G. C. (2003). Enhancing SME performance through vision-based

leadership: An empirical study. 16th Annual Conference conducted at the meeting of

Small Enterprise Association of Australia and New Zealand. Victoria, Australia.

Kantabutra, S., & Avery, G. C. (2007). Vision effects in customer and staff satisfaction: An

empirical investigation. Leadership and Organizational Development Journal, 28(3),

209-229.

Kantabutra, S. & Avery, G.C. (2010). The power of vision: Statements that resonate. Journal of

Business Strategy, 31(1), 37-45.

Kotter, J. P. (1990). A force for change: How leadership differs from management. New York:

Free Press.

Kouzes, J., & Posner, B. (1987). The leadership challenge. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Larwood, L., Falbe, C. M., Kriger, M. P., & Miesing, P. (1995). Structure and meaning of

organizational vision. Academy of Management Journal, 38(3), 740-769.

Levin, I. M. (2000). Vision revisited: Telling the story of the future. The Journal of Applied

Behavioral Science, 36(1), 91-107.

Lipton, M. (1996). Demystifying the development of an organizational vision. Sloan

Management Review, 37(4), 83-92.

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

23

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Lipton, M. (2004). Walking the talk (really!): Why vision fail. Ivey Business Journal Online,

January/February, 1-6.

Locke, E. A., Kirkpatrick, S., Wheeler, J. K., Schneider, J., Niles, K., Goldstein, H., Welsh, K.,

& Chah, D. (1991). The essence of leadership: The four keys to leading successfully. New

York: Lexington Books.

March, J. G., & Sutton, R. I. (1997). Organizational performance as a dependent variable.

Organizational Science, 8(6), 698-706.

McCullagh & Nelder, J. A. (1989). Generalized Linear Models (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, Fl.:

Chapman & Hall.

Mintzberg, H. (1991). The effective organization: Forces and forms. Sloan Management Review,

32(2), 54-67.

Murphy, G. B., Trailer, J. W., & Hill, R. C. (1996). Measuring performance in entrepreneurship

research. Journal of Business Research, 36(1), 15-23.

Nanus, B. (1992). Visionary leadership: Creating a compelling sense of direction for your

organization. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Palmer, B. (2004). Overcoming resistance to change. Quality Processes, 33(4), 35-39.

Parnell, J. A. (2000). Reframing the combination strategy debate: Defining forms of

combination. Journal of Applied Management Studies, 9(1), 33-54.

Parnell, J. A. (2005). Managing paradoxes in strategic decision-making. International Journal of

Management & Decision Making, 7(6), 708-724.

Parnell, J. A., & Carraher, S. (2001). The role of effective resource utilization on strategy’s

impact on performance. International Journal of Commerce & Management, 11 (3 & 4),

1-34.

Peters, T. (1987). Thriving on Chaos. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Quinn, R. E., & Rohrbaugh, J. (1983). A spatial model of effectiveness criteria: Towards a

competing values approach to organizational analysis. Management Science, 29(3), 363377.

Quigley, J. V. (1994). Vision: How leaders develop it, share it, and sustain it. Business Horizons,

37(5), 37-42.

Sashkin, M. (1988). The visionary leader. In J. A. Conger & R. N. Kanungo (Eds.), Charismatic

leadership: The elusive factor in organizational effectiveness (pp. 122-160). San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

24

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Sashkin, M. & Burke, W. W. (1987). Organization development in the 1980’s. Journal of

Management, 13(2), 393-418.

Schendel, D. E., & Hofer, C. W. (1979). Strategic management: A new view of business policy

and planning. Boston, MA: Little Brown and Company.

Senge, P. M. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art & practice of the learning organization. New

York, NY: Doubleday/Currency.

Seth, A., & Thomas, H. (1994). Theories of the firm: Implications for strategy research. Journal

of Management Studies, 31(2), 165-191.

Shim, J. K. & Siegel, J. G. (2000). Financial Management. Hauppauge, NY: Barrons.

Wang, H. (2002). CEO leadership attributes and organizational effectiveness: The role of

situational uncertainty and organizational culture. (UMI No. 3094775).

Westley, F., & Mintzberg, H. (1989). Visionary leadership and strategic management. Strategic

Management Journal, 10(special issue), 17-32.

Wiedower, K.A. (2001). A shared vision: The relationship of management communication and

contingent reinforcement of the corporate vision with job performance, organizational

commitment, and intent to leave. (UMI No. 3030139).

Yukl, G. (1998). Leadership in Organizations (4th ed). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

25

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Table 1

Correlations-Kendall’s tau

Kendall's tau

Correlations

Variables

Brevity

Claritygoal

Clartityime

Abstractness

Challenging

Future

orientation

Stability

Desire

Vision

attributes

roi2007

roa2007

Chgsales

Whoinput

Org.age

Org.size

clarity

goal

clarity

time

abstractness

challenging

1

.88**

.79**

.75**

1

.79**

.77**

1

.77**

1

.75**

.76**

.71**

.79**

.85**

.73**

.77**

.85**

.71**

.83**

.80**

.76**

.77**

-0.02

0.06

0.12

.71**

-0.04

0.11

.72**

-0.00

0.06

.14*

.76**

-0.08

0.05

.71**

0.01

0.07

.14*

.77**

-0.01

0.08

.85**

-0.05

-0.00

.12*

.72**

-0.04

0.07

Mean

1.39

0.59

1.01

2.60

2.15

Std.Dev.

1.62

0.56

0.96

2.71

2.33

brevity

1

.79**

.73**

.75**

.69**

2.40

3.06

1.85

2.74

2.87

2.12

1.88

500.1

502.9

1.06

1.44

26.18

90.99

1.77

39.53

36.77

0.20

1.56

23.98

791.76

future

orient.

stability

desire

.76**

.76**

.75**

1

.82**

.76**

1

.75**

1

.79**

-0.05

-0.02

.17*

.75**

-0.03

0.07

.86**

-0.05

0.03

.12*

.72**

-0.05

0.05

.77**

-0.03

0.04

.14*

.76**

-0.04

0.06

.81**

0.03

0.04

.15*

.68**

0.00

0.06

vision

attrib.

roi

2007

1

-0.04

0.00

.14*

.68**

-0.02

0.09

1

.53**

0.04

-0.03

0.03

0.05

** Correlation is significant at p < 0.01 (2-tailed)

* Correlation is significant at p < 0.05 (2-tailed)

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

26

roa

2001

1

-0.02

0.02

0.04

0.05

chg

sales

1

.14*

-0.00

.00

who

input

1

-0.06

0.02

org.

age

1

.29**

org.

size

1

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Table 2

Step 2: Mediating Effect –Vision Attributes and Whoinput

Parameter

(Intercept)

VA and Whoinput

(Scale)

(Intercept)

Brevity and Whoinput

(Scale)

(Intercept)

Clarity-Goals and Whoinput

(Scale)

(Intercept)

Clarity-Time and Whoinput

(Scale)

(Intercept)

Abstractness and Whoinput

(Scale)

(Intercept)

Challenging and Whoinput

(Scale)

(Intercept)

Future Orientation and

Whoinput

(Scale)

(Intercept)

Stability and Whoinput

(Scale)

(Intercept)

Desirability and Whoinput

(Scale)

a. Maximum likelihood estimate

b. p < 0.05

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

Parameter Estimates

95% Wald

Confidence Interval

Hypothesis Test

Std.

Wald ChiB

Error

Lower

Upper

Square

df Sig.

.408 .2421

-.067

.882

2.834

1 .092

.156 .0708

.017

.295

4.842

1 .028b

.271a .0383

.205

.357

.849 .1175

.619 1.079

52.190

1 .000

.034 .0422

-.049

.117

.651

1 .420

a

.282

.0397

.214

.371

1.325 .2544

.826 1.823

27.113

1 .000

-.378 .2381

-.845

.088

2.523

1 .112

a

.277

.0391

.210

.365

.573 .2217

.139 1.008

6.683

1 .010

.200 .1205

-.036

.436

2.756

1 .097

a

.276

.0390

.210

.364

.741 .1458

.456 1.027

25.870

1 .000

.041 .0293

-.016

.098

1.963

1 .161

a

.278

.0393

.211

.367

.509 .1280

.258

.760

15.774

1 .000

.107 .0306

.047

.167

12.229

1 .000b

.253a .0359

.192

.334

.901 .1160

.674 1.128

60.308

1 .000

.008 .0240

-.039

.055

1.01

1 .750

.283a

.619

.058

.279a

.890

.013

.283a

.0399

.2457

.0442

.0394

.1214

.0329

.0399

.215

.138

-.029

.212

.652

-.051

.215

.373

1.101

.144

.368

1.128

.078

.373

6.355

1.695

1 .012

1 .193

53.698

.162

1 .000

1 .687

27

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Table 3

Steps 3 and 4: Mediating Effect –Organizational Vision and Whoinput on Organizational Goals

Parameter Estimates

95% Wald

Confidence Interval

Parameter

B

Std. Error

(Intercept)

.284

.1103

Whoinput

-.029

.0808

VA and OG

-.129

.0714

a

(Scale)

.924

.1023

(Intercept)

.259

.1052

Whoinput

-.027

.0770

Challenging and OG

-.102

.0517

a

(Scale)

.920

.1019

(Intercept)

.168

.1077

Whoinput

-.055

.0788

Challenging and PS

-.041

.0529

a

(Scale)

.964

.1068

a. Maximum likelihood estimate

b. p < 0.05

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

Lower

.068

-.188

-.269

.743

.053

-.178

-.204

.740

-.043

-.210

-.145

.776

Hypothesis Test

Wald ChiUpper

Square

df Sig.

.500

6.620 1 .010

.129

.131 1 .718

.011

3.247 1 .072

1.148

.465

6.079 1 .014

.124

.125 1 .724

-.001

3.920 1 .048b

1.143

.379

2.437 1 .119

.099

.494 1 .482

.063

.605 1 .437

1.198

28

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

Table 4

Results of Alternative Hypotheses Testing

Alternative Hypotheses Testing Results

ALTERNATIVE HYPOTHESIS

H1: The aggregate of all of the vision attributes

(i.e. brevity, clarity, abstractness, challenge,

future orientation, stability, and desirability) has

a positive association with organizational

effectiveness.

H1a: Organizational vision statements with

brevity will have a positive association with

organizational effectiveness.

H1b: Organizational vision statements with

clarity will have a positive association with

organizational effectiveness.

H1c: Organizational vision statements with

abstractness will have a positive association with

organizational effectiveness.

H1d: Organizational vision statements that are

challenging will have a positive association with

organizational effectiveness.

H1e: Organizational vision statements that are

future oriented will have a positive association

with organizational effectiveness.

H1f: Organizational vision statements with

stability will have a positive association with

organizational effectiveness.

H1g: Organizational vision statements with

desirability will have a positive association with

organizational effectiveness.

H1h: Organizational effectiveness is enhanced

in organizations that have organizational vision.

H2: Organizational size positively moderates

the relationship of organizational vision to

organizational effectiveness.

H3: Organizational age positively moderates the

relationship of organizational vision to

organizational effectiveness.

H4: Organizational vision’s (aggregated)

influence on organizational effectiveness is

mediated through input into designing

organizational vision (i.e. whoinput).

RESULTS FINANCIAL

ROI ROA Change

in Sales

RESULTS NON-FINANCIAL1

Org.

Profitability Industry

Goals Satisfaction Growth

-

-

-

-*-

-

-

-

-

-

-*-

-

-

-

-

-

-*-

-

-

-

-

-

-*-

-

-

-

-

-

-*-

*

-

-

-

-

-*-

-

-

-

-

-

-*-

-

-

-

-

-

-*-

-

-

-

-

-

-*-

**

-

-

-

-

**

-

**

-

-

-

**

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

* Supported, p < 0.05

** Partially supported, p < 0.05

-*- Significant, negative relationship, p < 0.05

1

Note: the coefficients for Hypotheses H1a-H1h were negative for some of the non-financial indicators.

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

29

2013 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference

ISBN : 9780974211428

M2

Organizational Age

M1

Organizational Size

H2 (+)

H3 (+)

H1 (+)

ORGANIZATIONAL

EFFECTIVENESS

(OE)

ORGANIZATION

AL VISION

(OV)

-Brevity

-Clarity

-Abstractness

-Challenge

-Future Orientation

-Stability

-Desirability

-Financial Attributes

-Sales growth

-Return on equity

-Return on assets

H1a-H1h (+)

M3

WHOINPUT

-Non-Financial

Attributes

- Performance

satisfaction

- Industry vigor

H4 (+)

Figure 1. The figure presents the model of the relationship of organizational vision to

organizational effectiveness as moderated by organizational size and organizational age.

July 2-3, 2013

Cambridge, UK

30