Sustainability Strategies in Universities: Developing a Conceptual Framework

advertisement

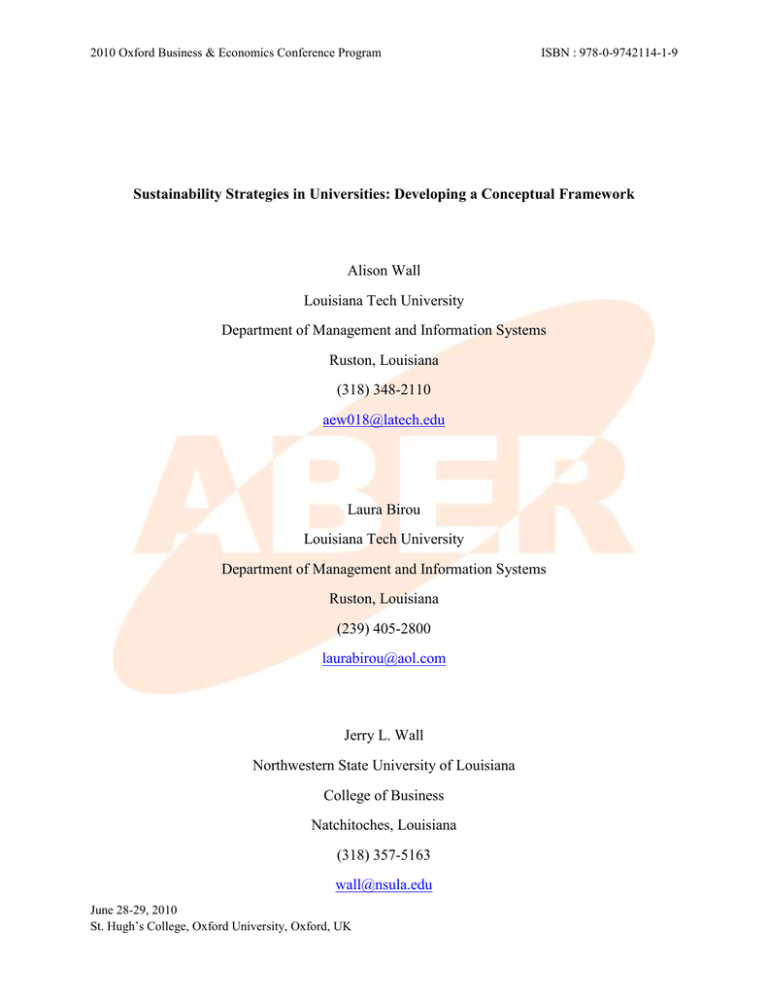

2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 Sustainability Strategies in Universities: Developing a Conceptual Framework Alison Wall Louisiana Tech University Department of Management and Information Systems Ruston, Louisiana (318) 348-2110 aew018@latech.edu Laura Birou Louisiana Tech University Department of Management and Information Systems Ruston, Louisiana (239) 405-2800 laurabirou@aol.com Jerry L. Wall Northwestern State University of Louisiana College of Business Natchitoches, Louisiana (318) 357-5163 wall@nsula.edu June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 ABSTRACT A 2009 corporate sustainability study involving 1,607 executives, from 36 countries, revealed that 84% of respondents planned to initiate company-wide sustainability strategies and 71% intend to maintain or increase their existing dedicated sustainability budget (Aberdeen 2009). This increased importance placed on sustainability strategies is reflected in the growth rate of clean energy jobs which has been more than double that of the rate for jobs in general between the years of 1998 and 2007 (The Pew Charitables Trust, 2009) and this trend is expected to continue. In spite of this business trend, institutions of higher education have not adopted sustainability strategies at the same rate, creating an increasing disparity between market needs and academic deliverables in the area of sustainability including adopting sustainability strategies, producing intellectual capital, and knowledge workers. The purpose of this paper is to provide a roadmap to close this gap by developing a framework for institutions of higher education (HE) to adopt sustainable strategies successfully. The barriers and the key success factors for execution will be identified through aggregating the results of individual case studies. This data will also be used to construct a framework for the adoption of sustainability strategies in university settings. INTRODUCTION The current concern around the development of sustainability strategies and their integration into mainstream intent in any organizational operations is very important and pertinent to the arena of higher education. Sustainability can be defined as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Bruntland, 1987). In higher education, the term describes initiatives that are aimed at increasing environmental accountability and social and environmental responsibility June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 1 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 (Nicolaides, 2006). There has been growing concern and adoption of sustainable strategies in Eastern universities for many years, evidenced by the number of published case studies (e.g. Nicolaides, 2006; Price, 2005; Wright T. S., 2004; Carpenter & Meehan, 2002; Dahle & Neumayer, 2001). In spite of this phenomenon, Western universities have been slow to adopt sustainability initiatives (Krucken, 2003), which is contrary to the idea that universities need to greatly reduce costs and benefit from an enhanced public image by being an initiator of sustainable development (Meyer & Konisky, 2007). Part of the reason that so few universities have adopted such strategies (Carpenter & Meehan, 2002) is due to the fact that much of the research on university and general organizational environmental policy is anecdotal, consisting of single university case studies with few attempts to combine the knowledge gained from these studies to present a cohesive framework for successful implementation. Further, there is no framework targeted specifically to universities in executing sustainability strategies. Given the inherent differences in the environments of the commercial sector, marked by market forces, government regulation, and industry activists and that of higher education driven by budgets, grants, tuition, and prestige, there is a need for such a model. In order to develop this framework, an overview of the organizational strategies that have been identified for societal and environmental initiatives will be presented. Then, those strategies executed in the university environment, will be presented. Finally, the model developed through a synthesis of case studies and other relevant research will be presented. This will be followed by ideas for future research, conclusions, and recommendations. The next section will be devoted to an exploration of the research addressing organizational change with respect to social responsibility. This will be followed by a narrower June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 2 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 band of research devoted to stakeholders in higher education specifically dealing with sustainability strategies. HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT/LITERATURE REVIEW Stakeholder Theory Prior research has addressed the need for a greater concentration and acknowledgment of the impact organizations have on the natural environment and have used a variety of theories to support the organization’s obligation or incentive to engage in sustainable environmental practices (Driscoll & Starik, 2004). However, researchers must demonstrate the presence of both intrinsic and extrinsic benefits (Tzschentke, Kirk, & Lynch, 2004). Intrinsic benefits and the personal motivations of managers alone are insufficient to create a drive for such practices and external factors such as cost reductions, subjective norms and negative consequences have proven to be more influential motivating factors (Flannery & May, 2000). Often the external factors come in the form of pressure from organizational stakeholders. Which forces the consideration of the natural environment a consideration in the organizational decision making process. Sensitizing organizational managers to the interconnectedness of their decisions and organizational outcomes and how they affect the natural environment and organizational performance (Flannery & May, 2000). Typically, when organizations attempt to address societal issues, they adopt the stakeholder theory approach and address the most urgent stakeholders’ needs first (Freeman, 1984). Stakeholder theory has been a cornerstone in the development of organizational policies and practices for almost thirty years because of the influence stakeholder groups possess which allows them to question prevalent institutional practices (Freeman, 1984; LaPlume, Sonpar, & June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 3 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 Litz, 2008). It often paves the way for organizations to have a purpose beyond that which is purely economic. Stakeholder theory is based on the theory of resource dependence that posits, in order to survive, organizations must recognize those who contribute (either voluntarily or involuntarily) to the achievement of goals and appropriately address their needs (LaPlume, Sonpar, & Litz, 2008). It was originally intended for use in strategic management but has been expanded into the realm of organization theory, business ethics, social issues, and, most recently, sustainable development (LaPlume, Sonpar, & Litz, 2008). Organizational stakeholders include any group or individual who can affect, or is affected by, the achievement of the organization's objectives" (Freeman, 1984). One important aspect of stakeholder theory is that it must include both voluntary stakeholders, those who have invested some form of capital in the organization, and involuntary stakeholders, those who are involved through placement into a potentially hazardous position by the firm’s actions (Mitchell, Alge, & Wood, 1997). Prior to 1995 nonhuman forms, other than corporations or representative organizations, were not considered as stakeholders because they did not have a recognizable will or desire and/or did not have the power to politically punish the organization for failing to address their needs (Starik, 1995). In addition, stakeholders can be either beneficiaries or risk-bearers of organizational practices (Post, Preston, & Sachs, 2002), which expands the pool of organizational stakeholders to include boundary-less groups, such as the natural environment. However, exclusion of the natural environment can lead to serious consequences in light of the magnitude of vital resources derived from it that are essential for the performance of organizations (Starik, 1995). Previous arguments have put forth the notion that the natural environment is only able to impact organizational performance indirectly through governmental regulations or representative groups’ influence (Orts & Strudler, 2002). Given the conflicting June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 4 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 views of these groups concerning best practices for addressing environmental issues and the increased cost associated with governmental regulations and compliance failures (Russo & Fouts, 1997), this lack of direction and legal authority results in organizational compliance to minimal requirements (Chen, 2001). If organizations expand their priorities to include the natural environment in their strategic planning of both their political initiatives and organizational decisions, they can better address potential problems that can affect their longterm survival. The benefit of using stakeholder theory to make what appears to be intangible issues appear tangible, and therefore, actionable allows organizational decision makers to include the natural environment in strategic planning (Clarkson, 1995). In addition, recent research shows that when an organization has poor environmental performance, the relationship of the organization with many of their stakeholder groups becomes strained (Buysse & Verbelke, 2003). This relationship has become increasingly important, as more organizational stakeholders perceive that companies that do not undertake some discretionary societal initiatives are unethical (Williams, 2009). The job of stakeholder theorists is to identify and support the inclusion of any given entity, as a stakeholder in terms of the general characteristics a stakeholder possesses (Phillips & Reichart, 2000). Many theorists implement a narrow definition of a stakeholder as an individual or group that has the ability to affect firm economic performance directly, while others implement a broad definition. The broad definition, which is typically used by theorists attempting to include moral and social issues such as human rights and the natural environment, awards stakeholder status based on moral and ethical obligation and includes any that have an indirect ability to affect firm performance (LaPlume, Sonpar, & Litz, 2008). However, the broad definition do not provide any insight into how organizations can go about balancing the interests between various stakeholders June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 5 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 (Orts & Strudler, 2002) and is considered by many to be the cause of criticisms of stakeholder theory as a whole due to the treatment of a stakeholder as both the means and the ends of organizational decisions (LaPlume, Sonpar, & Litz, 2008). This treatment may lead to increased misappropriations and misallocations of funds and other organizational resources (Margolis & Walsh, 2003) and create confusion by expanding decision-making beyond the formal legal and economic boundaries of organizations. In addition, a narrow definition of a stakeholder that focuses strictly on economic and financial interests has greater appeal and is more easily incorporated into the long-term goal attainment of a firm (Orts & Strudler, 2002). Regardless of the definition used, the inclusion of the natural environment as an organizational stakeholder is still controversial; however, there remains widespread adoption of stakeholder identification theory by organizational managers when determining which trade-offs to make among various goals and objectives (Mitchell, Alge, & Wood, 1997). This adoption may be due in part to societal pressure for organizations to make positive contributions to the material well-being of society as a whole rather than simply addressing the needs of shareholders (Margolis & Walsh, 2003). Further, the stakeholder issues that organizations consider affect the type environmental policies that they adopt (Sharma & Henriques, 2005). The increased interest of all stakeholders and the quantity of governmental regulations encourages organizational decision maker’s to find a way to integrate sustainable practices into organizational processes. Stakeholder theory is recognized as a viable option through which organizations can address sustainability strategies. Its use in developing sustainable strategies facilitates organizational decision makers understanding of the contextual circumstances in which sustainable strategies will be successful. June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 6 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 There exist two main theoretical approaches for stakeholder research and identification. The first, which is used in this paper, is a normative theory of stakeholder identification, in which researchers identify and logically explain the reasons for inclusion of certain groups as stakeholders (Mitchell, Alge, & Wood, 1997). The second is a descriptive theory of stakeholder salience, in which researchers identify the conditions surrounding the inclusion/exclusion of stakeholder groups in management’s thinking (Mitchell, Alge, & Wood, 1997). The instrumental approach focuses on how firm behaviors affect performance is a third less common approach (LaPlume, Sonpar, & Litz, 2008). Stakeholder theory allows organizational decision makers to consider factors that are common regardless of the methods through which they choose to incorporate societal and environmental initiatives into their overall strategies, an overview of which will be presented next. Organizational Strategies for Societal and Environmental Initiatives Societal initiatives are those that are beyond the scope of the typical economic, legal, and ethical responsibilities that are required by stakeholder groups and have been traditionally been considered discretionary. There are four basic approaches: reactive, defensive, accommodative, and proactive that organizations implement when adopting societal initiatives (e.g. Carroll, 1979; Clarkson, 1995; Jawahar & McLaughlin, 2001). Organizations can use one of the four strategies, or a combination thereof, to address the interests of different stakeholder groups (Jawahar & McLaughlin, 2001). The four strategies each offer distinct advantages and a brief overview is provided next. A reactive strategy is on in which an organization attempts to fight against societal expectations and typically denies any culpability while refusing to address the needs of the stakeholder adequately. An example of this type of strategy is evident in cosmetics companies June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 7 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 continued use of lead in their lipsticks. In spite of stakeholder concerns, most companies continue to use lead in the lipstick formulas, as there are no governmental regulations against its use (Hepp, Mindak, & Cheng, 2009. Other examples would be the use of child labor and animal testing in the production of goods. A defensive strategy involves doing the minimum that is legally required, such as following government standards like ISO 14000 and Environmental Protection Agency regulations. While the organization does more than in the previous strategy by admitting fault, they only do what is legally mandated. Defensive strategies are considered a more legalistic/public-relations oriented approach. Defensive strategies are considered a form of damage control, or a copycat strategy and offer no distinctive competitive advantage, merely nullifying any disadvantage. Examples of defensive posturing include the recent incident with Toyota in which, at first, they denied a problem only to admit the severity and prior knowledge they had of the situation under immense public pressure (Toyoda, 2010). Another recent example of defensive strategies is evident in the issues on Wall Street. Organizational decision makers knew they had taken extreme levels of risk and the potential collapse; however, they only adjusted their behaviors after governmental entities intervened. An accommodative strategy involves the use of progressive actions to address stakeholder concerns when they arise. This is also known as a quick response in this strategy; the company does all that can be expected to address the concerns, but does not take any future preventative steps. An example of an accommodative strategy is in SIGG’s recent recall of their water bottles after discovering the bottles contained bysphenol-A. Although there is no governmental regulation requiring companies to remove the chemical from their products, SIGG issued a voluntary recall of all of their products for free replacement (Northrup, 2009). June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 8 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 Proactive strategies are those in which the organizational decision makers attempt to recognize stakeholder issues before they occur and prevent them from occurring. Those with a proactive strategy are typically the industry leaders who are selected for benchmarking by other organizations and are consulted when governmental regulations are being developed (Buysse & Verbelke, 2003). Many companies have adopted a proactive sustainability strategy by creating green zones around their office buildings and industrial parks. A specific example of this type of strategy is evident in Subaru’s achievement of creating zero landfill waste and becoming a dedicated wildlife refuge. These initiatives have yet to be adopted by competitors, creating a position for Subaru to lead the industry in environmental policies (Subaru Environmental Policy, 2010). The most thorough proactive strategies begin at the product design stage and commonly referred to as a "cradle to cradle" approach whereby an organization attempts to transform products through the incorporation of ecologically intelligent design (McDonough & Braungart, 2002). Disney incorporated a proactive approach by reformulating all of the foods sold in their theme parks to remove all transaturated fat below the global limits of 2-5 percent (Department of Health and Human Services: Food and Drug Administration, 2003) and further removed all of their characters from any junk food promotions. As CEO Robert Iger stated, “A company such as ours, with the reach we have, has a responsibility because of how much we can influence people’s opinions and behavior. There’s also a business opportunity here.” (Marr & Adamy, 2006). Although there is no conclusive evidence that sustainability leads to increased performance, there has been evidence of reduced costs, and most organizations have adopted or plan to adopt sustainability initiatives (The Pew Charitables Trust, 2009). Regardless of which of the approaches organizational decision makers adopt, or which sustainability strategies they June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 9 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 incorporate, there are likely to be similar factors surrounding the success and/or failure of the strategies. Examples of common factors include making investments in sustainable competencies related to production and manufacturing of goods and services, employee training and skills, research and development, accounting, organizational policy, and strategic planning (Buysse & Verbelke, 2003). Given this phenomena, the development of a framework through which organizational decision makers can successfully identify and adopt sustainability strategies is necessary. By focusing this paper on a specific industry, i.e. higher education, the scope and potential factors of adoption of sustainable strategies is narrowed to provide a foundation that can be used to address their role for other organizations and industries. SUSTAINABILITY IN UNIVERSITIES Universities are a unique environment in that they are driven by market share and reputation, not by profits. In addition, their main contributions to society are through their research and their ability to educate students not through a tangible product. While there exist several opportunities for universities to pursue external funds through grants and contracts, universities typically do not have a plethora of internal discretionary funds with which to make investments in new technologies and developments on their campuses, further creating a unique situation in which universities may operate. In spite of limited funds, many expect universities to be at the forefront of movements such as sustainability and serve as the main source of change in corporate strategies through the provision of knowledge workers who can create, develop and implement new strategies (Krucken, 2003). In spite of a general recognition that sustainable policies are needed and increased adoption among organizations, universities have been slow to adopt such policies within their own organizational structure. Developing an understanding of the differences behind adoption and success of sustainable policies in universities and June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 10 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 corporations can help to clarify which sustainability strategies are most likely to succeed in a given university environment, e.g. recycling, waste reduction, etc. Even though the need for sustainable policies in universities has been recognized since the early 1970s, much has centered around the need for education rather than the impact that universities have on the environment (Clarke, 2006) and many United States institutions are only now beginning to adopt these policies. While the external business environment has continued to adapt and adopt new environmental technologies creating a demand for knowledge workers that understand these issues, universities have been slow to adjust by adopting additional classes and experiential opportunities (Krucken, 2003). This disconnect creates a problem for universities in that no firm can maintain a sustainable competitive advantage without the support of firm level competencies (Barney, 1991), in this case, the ability to prepare students for a position in a firm that has adopted environmental strategies or technologies would be considered a firm level competency. Additionally, many organizations that adopt sustainability initiatives use inaccurate, uneven, or ill-communicated measures of success that has resulted in a negative impact on the efficiency, quality and resilience of their programs (Aberdeen Group, 2009). As long as universities remain a main source of knowledge workers, it is reasonable to suggest that the universities that provide sustainability education and allow practical application stand to benefit greatly and will have more competitive graduates who can fill this unmet demand (Christensen, Thrane, Jorgensen, & Lehmann, 2009). In spite of these opportunities, most universities have adopted reactive or defensive strategies and only implemented sustainable initiatives when government policy mandates it (Krucken, 2003). While this strategy is largely attributable to funding issues that are prevalent at most universities (Carpenter & Meehan, 2002) it may place a university at a distinct June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 11 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 disadvantage when attempting to attract new students and place its graduates at leading organizations. Attempts at actively pursuing sustainability strategies are evident in a variety of declarations adopted by many universities that will be briefly discussed next. Declarations of Sustainability The following provides a brief overview of the main declarations of sustainability, for a more in depth review, see Wright, 2002, and Nicolaides, 2006. The first university directed sustainability declarations was the Stockholm Declaration, followed by the more formal Tbilisi Declaration in the 1970s (Wright, 2002). Each of these declarations made incremental advances towards the recognition and implementation of sustainability strategies. Several other declarations were also drafted during the 1970s and 80s, but the Talloires Declaration of 1990 is considered the most significant with over 280 universities signatures (Nicolaides, 2006). The significance of the Talloires Declaration is that it was the first to involve university administrators in the developmental process, however, Wright (2002) and Nicolaides (2006) report that many of the signatories have not actually adopted the policies and practices put forth in the declaration. Therefore, this voluntary signing of declarations may be construed as an agreement in principal, but not a proactive strategy. In fact, the signing of declarations may not facilitate efforts as it allows universities to promote their status as a signatory while not adopting sustainability and still benefiting from enhanced public image, i.e. “greenwashing” (Nicolaides, 2006). Paradoxically, many universities that have not taken the step to sign such declarations have adopted environmental policies more readily than signatory universities (Wright, 2002). In fact, over 60% of universities that have adopted environmental policies do not publicize them (Price, 2005). June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 12 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 Researchers have also found that universities do not have to adopt full environmental management systems as called for in many of the declarations in order to be successful; however, they do need to adopt formal environmental policies (Spellerberg, Buchan, & Englefield, 2004). Given these findings, it becomes even more important to develop an understanding of which university strategies were successful and the factors, such as stakeholder interests, surrounding successful adoption of environmental policies. In fact, this research is that addresses the current gap in knowledge and information is called for in Wright (2002). The current research is an attempt to fill this gap by developing a framework. The next section, is dedicated to the development of the through the utilization of stakeholder theory. UNIVERSITY STAKEHOLDERS Several factors may affect the success of sustainability strategies in universities. In order to adopt appropriate sustainability strategies and potentially fill the demand for skilled knowledge workers, universities must recognize and identify their stakeholders. For universities these stakeholders include students, faculty, staff, administration, local communities, potential employers, alumni, grants, funding institutions, contract entities, and others. Stakeholder relationships are increasingly important for universities as two of their main sources of income are from alumni, student tuition, taxes, and the employers of graduates through endowed professorships and classroom buildings. Research conducted by the Bridgespan Group indicates that there was a 79% increase in sustainability courses between 2005 and 2007 in United States MBA programs (Stone, Ciccarone, & Deshpande, 2009). Students were identified as the major contributing force for this growth due an increasingly service-oriented culture. The service-learning pedagogy is based June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 13 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 upon the idea that students gain meaningful experiences through volunteer work and community service, beginning early in the educational years and are increasingly prolific in high school and undergraduate programs. Students coming from these backgrounds expect the opportunity to continue these experiences in their upper-level educational activities, which explains the increase in presence and demand for sustainability courses in MBA programs. Several studies have found that greater levels of similarities between student’s values, goals, and attitudes and the university mission and policies will result in a lower propensity for the student to drop out (Jevons, 2006) and increased loyalties to the university. These interests and the service-orientation of students creates an opportunity for universities, especially business schools, to provide hands on experience that is relevant to practical application by adopting sustainability strategies. As students become more interested and active in sustainability initiatives they will seek universities that adopt those same attitudes and environments to encourage the development of knowledgeable employees that can provide cross-sector experience (Stone, Ciccarone, & Deshpande, 2009). In addition, universities can generate further adoption through the attainment of grants and publicity, and likely, attract more students and higher quality faculty. Therefore based on this prior research, student interest will be included as a variable in the framework (Stone, Ciccarone, & Deshpande, 2009; Jevons, 2006). Through student and faculty involvement the University of Maine Farmington will be able to save more than $17,000 per year in energy costs, 125 tons of carbon, and 164,000 kilowatt-hours of energy due to faculty and students pledged commitment to turn off their computers and purchase ones that are energy-star compliant (Schaffhauser, 2009). In fact, faculty members and their interests have been found to be the second most significant driver of the adoption of sustainability curriculum is faculty interest (Stone, Ciccarone, & Deshpande, June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 14 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 2009). At Harvard University’s Social Enterprise Initiative, over 95 faculty members have agreed to participate through research and teaching, creating over 400 social enterprise cases (The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business, 2009). The results of the previously mentioned study and the experience at Harvard attribute reasons for the failure of sustainable policies to a lack of commitment and acceptance from faculty and staff and a lack of understanding regarding the effects of university activities on the environment (Christensen, Thrane, Jorgensen, & Lehmann, 2009). Other research indicates a need to expand the initiatives beyond just faculty members and consider cross-discipline interactions, as well as the involvement of upper administration, which may be especially difficult at larger universities. Organizational research suggests that when employees are not convinced of the need for sustainable initiatives or the organizations commitment, they must be convinced in order for the initiatives to succeed (Newton, 2002). A lack of administrative involvement has been credited by several researchers as the main cause for failing sustainable initiatives (Krucken, 2003), in fact, over 50% of colleges within universities that have implemented these policies have failed to involve senior administration (Carpenter & Meehan, 2002). Given that senior administrators frequently interact with local communities and provide universities with publicity, it seems logical that their involvement would be crucial to the success any initiative. Based on previous research, this dynamic will be captured in the concept of organizational commitment (Schaffhauser, 2009 Stone, Ciccarone, & Deshpande, 2009; The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business, 2009; Christensen, Thrane, Jorgensen, & Lehmann, 2009; Newton, 2002; Krucken, 2003; Carpenter & Meehan, 2002). Local communities provide a variety of support for universities by supplying staff and other support and it is necessary that for universities to maintain a working and functional June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 15 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 relationship with them. Therefore, it is important for universities to consider their impact on their local community through the waste that is produced by students and their consumption of resources. An opportunity to interact with the local community was adopted by the University of Vermont in Burlington in which they collect food waste from various locations around campus and take it to a composting site run by a local nonprofit business (FM Staff, 2004). Another example of universities interacting with local communities is a George Washington University where students created a community garden to provide food for homeless shelters, aesthetic landscaping, and educational opportunities (George Washington University). Assessment of this consideration will be captured in the concept of community interest (FM Staff, 2004; George Washington University). In spite of the opportunities to cut costs significantly, environmental initiatives are often the first to go during budget cuts, especially when those cuts occur soon after adoption (Leal Filho & Wright, 2002). This creates a unique opportunity for universities to pursue additional funding through their other stakeholder groups, such as grant provider, businesses, or research contracts. Syracuse University took advantage of a collaborative relationship in this manner and was able to join with IBM and the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority to build a $12-million green computer center that will use half the energy of a typical computing center (Nagel, 2009). The University of Minnesota-Morris also took advantage of a collaborative relationship by partnering with McKinstry, a construction engineering, energy services, and facility management firm which will help the university reach its goal of becoming the first carbon-neutral university in the Midwest by 2010 (Schaffhauser, U Minnesota Morris Pursues Carbon Neutrality by 2010, 2009). Therefore, collaborative partnerships will be included (Leal Filho & Wright, 2002; Nagel, 2009; Schaffhauser, U Minnesota Morris Pursues June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 16 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 Carbon Neutrality by 2010, 2009). These are just a couple of the examples of successful sustainability strategies that have been implemented by universities, a better understanding of the contextual factors and outcomes of sustainability strategies will provide insight into the best practices for individual universities to adopt. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK The model presented in this paper is exploratory and integrates stakeholder interests to help universities move from adopting discrete strategic initiatives to adopting holistic and successful sustainability strategies. The framework developed considers the impact of student interest, organizational commitment, community involvement, and collaborative partnerships in the creation of sustainability strategies. Student interest involves both the interest in taking classes in sustainability education and practices, but also their interest in developing and initiating sustainability practices at their university and in the community. The organizational commitment construct involves the level of interest faculty, staff, and administration have in teaching sustainability programs, serving as academic advisors for student initiatives, researching sustainability programs and potential developments and serving on university sustainability committees. The collaborative partnership construct includes perceptions of university adoption of sustainability strategies and the business’s interest in participating in cooperative endeavors with the university through joint development and financial commitments. The community interest construct will involve a measure of local community need for and perceived impact of the adoption of sustainability strategies at universities. Potential moderators include funding and budget constraints, cross-disciplinary approaches, and upper administration involvement. Outcomes include improved stakeholder perceptions, increased placement of graduates, increased levels of student recruitment and retention, and increased alumni donations. June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 17 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 Figure 1: Conceptual Framework Student Interesta Community Perceptions + Organizational Commitmentb + Sustainable Strategies + Collaborative Partnershipsc + Community Interestd + Graduate Placement Student Recruitment and Retention Alumni Donations Construct Development Note: a (Stone, Ciccarone, & Deshpande, 2009; Jevons, 2006) b (Schaffhauser, 2009 Stone, Ciccarone, & Deshpande, 2009; The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business, 2009; Christensen, Thrane, Jorgensen, & Lehmann, 2009; Newton, 2002; Krucken, 2003; Carpenter & Meehan, 2002). c (Leal Filho & Wright, 2002; Nagel, 2009; Schaffhauser, U Minnesota Morris Pursues Carbon Neutrality by 2010, 2009) d (FM Staff, 2004; George Washington University) FUTURE RESEARCH Future research should involve collecting data from universities in order to assess the proposed relationships identified by research and delineated in the conceptual framework. Given that the majority of research on university adoption of sustainable strategies is on single case studies, a potential direction for future research would be to combine the results of the current strategies in order to better develop a list of successful factors. While Wright (2004) created a June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 18 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 guideline for the adoption of sustainable policies, her recommendations were based on the results of a single university in Canada. In addition, very little academic research has been conducted in the United States on this topic as it pertains to universities and a comparison needs to be made between Eastern and Western universities. Several universities have begun to adopt energy efficiency plans and waste reduction plans which indicate a potential interest in this topic and a potential for data collection. As these initiatives take effect and universities begin to see results, there could be even greater opportunity to identify key sustainability strategies that universities can implement and perhaps carry over into the external business environment. CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS The reason that a university setting is the focus of this paper is that universities, act as an incubator of ideas, are in a unique position to affect future business leaders and practices. This paper develops a conceptual model based on prior research, which identifies the independent variables necessary to execute a sustainable strategy at a university level effectively. While so universities have begun to adopt sustainability strategies, the majority have only taken the bare minimum approach neither preparing their students to lead in the green economy nor fulfilling their obligation to stakeholders in the employment sector for clean energy jobs. The lack of sustainability adoption also creates a problem for the development of future initiatives (Wright, 2002). This problem is created because research professors may not feel encouraged to participate in sustainable research activities (Christensen, Thrane, Jorgensen, & Lehmann, 2009) due to decreased rewards and recognitions than are associated with research that is more in line with the goals and orientation of the university or their disciplines. As universities begin to examine the potential towards the development of sustainability strategies, they should June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 19 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 consider the perspectives of their stakeholders as well as their ability to continue providing a quality product, i.e. educated students and advances in education. In addition, universities should identify their basic values and contributions and create their strategies in a bottom-up approach in order to ensure they are appropriate. This puts universities in a unique position to affect the legitimacy and adoption of desirable and innovative organizational strategies, such as sustainability, through developing an interest and skill level in their graduates that prepares them to confront these issues and strategies in an organizational setting. June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 20 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 REFERENCES Aberdeen Group. (2009). Sustainability is the New "Green" - Research of 1,607 Executives from 36 countries identifies sustainability as one of the top 5 priorities in 2009. Boston: Harte-Hanks Company. Barney, J. (1991). Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management , 17 (1), 99-120. Bruntland, G. (1987). Our Common Future. The WOrld COmmission on Environment and Development. Buysse, K., & Verbelke, A. (2003). Proactive Environmental Strategies: A Stakeholder Management Perspective. Strategic Management Journal , 24 (5), 453-470. Carpenter, D., & Meehan, B. (2002). Mainstreaming environmental management: Case studeis from Australasian universities. International Journal of Sustainabilitiy in Higher Education , 3 (1), 19-37. Carroll, A. (1979). A Three Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Social Performance. Academy of Management Review , 4, 497-505. Chen, C. (2001). Design for the Environment: A Quality-Based Model for Green Product Development. Management Science , 47 (2), 250-263. Christensen, P., Thrane, M., Jorgensen, T. H., & Lehmann, M. (2009). Assessing the gap between preaching and practice at Aalborg University. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education , 10 (1), 4-20. June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 21 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 Clarke. (2006). The Campus Environmental Management System Cycle in Practice. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education , 7 (4), 374-389. Clarkson, M. (1995). A Stakeholder Framework for Analyzing and Evaluating Corporate Social Performance. Academy of Management Review , 20, 92-117. Dahle, M., & Neumayer, E. (2001). Overcoming barriers to campus greening: A survey among higher educational institutions in London, UK. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education , 2 (2), 139-160. Department of Health and Human Services: Food and Drug Administration. (2003). Federal Register - 68 FR 41433 July 11, 2003: Food Labeling; Trans Fatty Acids in Nutrition Labeling; Consumer Research to Consider Nutrient Content and Health Claims and Possible Footnote or Disclosure Statements; Final Rule and Proposed Rule. Driscoll, C., & Starik, M. (2004). The Primordial Stakeholder: Advancing the Conceptual Consideration of Stakeholder Status for the Natural Environment. Journal of Business Ethics , 49, 55-73. Flannery, B. L., & May, D. R. (2000). Environmental Ethical Decision Making in the US MetalFinishing Industry. Academy of Management Journal , 43 (4), 642-662. Freeman, R. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Boston: Pitman/Ballinger. George Washington University. (n.d.). George Washington University. Retrieved February 20, 2010, from Community: http://www.gwu.edu/connect/community Henriques, I., & Sharma, S. (2005). Pathways of Stakeholder Influence in the Canadian Forestry Industry. Business Strategy and the Environment , 14, 384-398. June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 22 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 Hepp, N. M., Mindak, W. R., & Cheng, J. (2009). Determination of total lead in lipstick: Development and validation of a microwave-assisted digestion, inductively coupled plasma– mass spectrometric method. Journal of Cosmetic Science , 60, 405-414. Jawahar, I., & McLaughlin, G. L. (2001). Toward a descriptive Stakeholder Theory: An Organizational Life Cycle Approach. Academy of Management Review , 26 (3), 397-414. Jevons, C. (2006). Universities: a prime example of branding going wrong. Journal of Product and Brand Mangement , 15 (7), 466-467. Krucken, G. (2003). Learning the 'New, New Thing': On the Role of Path Dependency in University Structures. Higher Education , 46 (3), 315-339. LaPlume, A. O., Sonpar, K., & Litz, R. A. (2008). Stakeholder Theory: Reviewing a Theory That Moves Us. Journal of Management , 34, 1152-1189. Leal Filho, W., & Wright, T. S. (2002). Barriers on the path to sustainability: Eurpoean and Canadian perspectives in higher education. International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology , 9 (2), 179-186. Margolis, J. D., & Walsh, J. P. (2003). Misery Loves Companies: Rethinking Social Intiatives by Business. Administrative Science Quarterly , 48 (2), 268-305. Marr, M., & Adamy, J. (2006, October 17). Disney Pulls Its Characters From Junk Food: Move Sets Limits on Fats, Sugar And Calories in Product Tie-Ins; Getting a Pass on Birthday Cakes. Wall Street Journal . McDonough, W., & Braungart, M. (2002). Cradle to Crade: Remaking the Way We Make Things. North Point Press. June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 23 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 Meyer, S., & Konisky, D. (2007). Adopting Local Environmental Institutions: Environmental Need and Economic Constraints. Political Research Quartlerly , 60 (1), 3-16. Mitchell, R. K., Alge, B. R., & Wood, D. J. (1997). Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts. Academy of Management Review , 22 (4), 853-896. Nagel, D. (2009). Syracuse U Aims for Greener Data Center. New York. Newton, T. (2002). Creating the New Ecological Order? Elias and Actor-Network Theory. The Academy of Management Review , 27 (4), 523-540. Nicolaides, A. (2006). The implementation of environmental management towards sustainable universities and education for sustainable development as an ethical imperative. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education , 7 (4), 414-424. Northrup, L. (2009, August 26). SIGG will replace BPA-containing Bottles for Free. Retrieved from The Consumerist: http://consumerist.com/2009/08/sigg-will-replace-bpa-containingbottles-for-free.html Orts, E. W., & Strudler, A. (2002). The Ethical and Environmental Limits of Stakeholder Theory. Business Ethics Quarterly , 12 (2), 215-233. Phillips, R. A., & Reichart, J. (2000). The Environment as a Stakeholder? A Fairness Based Approach. Journal of Business Ethics , 23, 185-197. Post, J., Preston, L., & Sachs, S. (2002). Redefining the Corporation: Stakeholder Management and Organizational Wealth. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 24 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 Price, T. J. (2005). Preaching what we practice: experiences from implementing ISO 14001 at the University og Glamorgan. International Journal of Sustainability in Highrer Education , 6 (2), 161-178. Russo, M. V., & Fouts, P. A. (1997). A Resource-based Perspective on Corporate Environmental Performance and Profitability. Academy of Management Journal , 40 (5), 534-559. Schaffhauser, D. (2009). U Minnesota Morris Pursues Carbon Neutrality by 2010. Schaffhauser, D. (2009, 4 30). UMF Green Pledges Could Save 3,000 Tons of Carbon Annually. Campus Technology . Sharma, S., & Henriques, I. (2005). Stakeholder Influences on Sustainability Practices in the Canadian Forest Products Industry. Strategic Management Journal , 26, 159-180. Spellerberg, I. F., Buchan, G. D., & Englefield, R. (2004). Need a universoty adopt a formal environmental management system? Progress without an EMS at a small university. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education , 5 (2), 125-132. Staff, F. (2004, June 1). Waste is a Terrible Thing to Mind. Food Management . Starik, M. (1995). Should Trees Have Managerial Standing? Toward Stakeholder Status for NonHuman Nature. Journal of Business Ethics , 14, 207-217. Stone, N., Ciccarone, M., & Deshpande, R. (2009). The MBA Drive for Social Value: Five Trends boosting social benefit content at U.S. Business Schools. New York: The Bridgespan Group, Inc. June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 25 2010 Oxford Business & Economics Conference Program ISBN : 978-0-9742114-1-9 Subaru Environmental Policy. (2010). Retrieved 2010, from Subaru: http://www.subaru.com/company/environmental-policy.html The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business. (2009). Business Schools and Sustainability: Effective Practices. The Pew Charitables Trust. (2009). The Clean Energy Economy: Repowering jobs, Business, and Investments Across America. Washington, D.C. Toyoda, A. (2010). Prepared Testimony Akio Toyoda, President, Toyota Motor Company Committee On Oversight and Government Reform. Toyota Motor Company. Tzschentke, N., Kirk, D., & Lynch, P. (2004). Reasons for going green in serviced accomodation establishments. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management , 16 (2), 116124. Williams, C. (2009). Ethics and Social Responsibility. In MGMT2 (pp. 58-75). Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning. Wright, T. S. (2004). Consulting stakeholders in the development of an Environmental Policy Implementation Plan: a Delphi Study at Dalhousie University. Environmental Education Research , 10 (2), 179-194. Wright, T. S. (2002). Definitions and frameworks for environmental sustainability in higher education. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education , 3 (3), 203-220. June 28-29, 2010 St. Hugh’s College, Oxford University, Oxford, UK 26