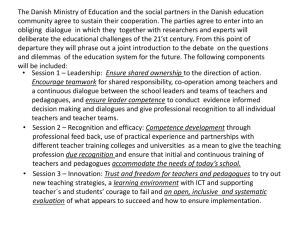

National Report: Denmark

advertisement